What Happened in October 1861

I

McClellan Pushes Scott Out the Door

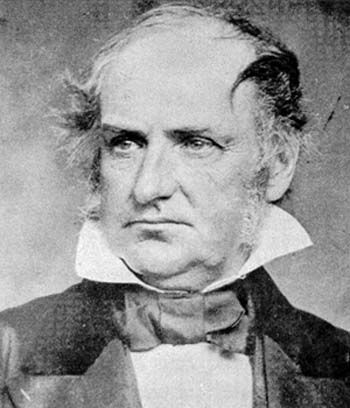

By October 1861, McClellan had gone far toward reorganizing the army into brigades and divisions officered by men of his selection. In the course of doing this, McClellan ignored General Scott completely, causing the general-in-chief to tender his resignation to Lincoln which was accepted.

WASHINGTON, Oct. 31, 1861.

Hon. S. Cameron, Secretary of War:

SIR: For

more than three years I have been unable, from a hurt, to mount a horse, or to

walk more than a few paces at a time, and that with much pain. Other and new

infirmities -- dropsy and vertigo -- admonish me that the repose of mind and

body, with the appliances of surgery and medicine, are necessary to add a

little more to a life already protracted much beyond the usual span of man. It

is under such circumstances, made doubly painful by the unnatural and unjust

rebellion now raging in the Southern States of our so lately prosperous and

happy Union, that I am compelled to request that my name be placed on the list

of army officers retired from active service. As this request is founded on an

absolute right, granted by a recent act of Congress, I am entirely at liberty

to say it is with regret that I withdraw myself in these momentous times from

the orders of a President who has treated me with much distinguished kindness

and courtesy; whom I know, upon much personal intercourse, to be patriotic,

without sectional partialities or prejudices; to be highly conscientious in the

performance of every duty, and of unrivaled activity and perseverance.

SIR: For

more than three years I have been unable, from a hurt, to mount a horse, or to

walk more than a few paces at a time, and that with much pain. Other and new

infirmities -- dropsy and vertigo -- admonish me that the repose of mind and

body, with the appliances of surgery and medicine, are necessary to add a

little more to a life already protracted much beyond the usual span of man. It

is under such circumstances, made doubly painful by the unnatural and unjust

rebellion now raging in the Southern States of our so lately prosperous and

happy Union, that I am compelled to request that my name be placed on the list

of army officers retired from active service. As this request is founded on an

absolute right, granted by a recent act of Congress, I am entirely at liberty

to say it is with regret that I withdraw myself in these momentous times from

the orders of a President who has treated me with much distinguished kindness

and courtesy; whom I know, upon much personal intercourse, to be patriotic,

without sectional partialities or prejudices; to be highly conscientious in the

performance of every duty, and of unrivaled activity and perseverance.

And to you, Mr. Secretary, whom I now officially address for the last time, beg to acknowledge my many obligations for the uniform high considerations I have received at your hands, and have the honor to remain, Sir, with high respect,

Your obedient servant,

(Signed) WINFIELD SCOTT.

II

McClellan's First Effort at Crossing the Potomac Is a Fiasco

By the middle of October, the expanding Union force gathering in front of Alexandria caused Confederate general Joe Johnston to abandon his outposts close to the Union forts and draw them in to his main body which occupied Centreville. McClellan, according to his testimony before the Committee on the Conduct of the War, sent Charles Stone, a colonel in the Regular Army and a brigadier-general of Volunteers, an order to advance his force, which then was some distance behind the left bank of the Potomac, to the shore and show themselves—his object, he said, being merely to "keep a sharp lookout whether the enemy abandoned Leesburg."

Stone interpreted McClellan's order somewhat differently. Instead of simply showing troops and making a feint of crossing the river, Stone decided to use his boats—two flat boats, a second-hand ferry, and several skiffs—to "try my boats, to see how rapidly they could push troops over." Stone had a small body of troops occupying Harrison's Island, and he ordered these, under Colonel Devin, to go to the right bank of the river and move toward Leesburg, to see if the enemy occupied it. In the course of doing this, Devin found enemy troops of a small number camped near the town. Learning this, Stone ordered Devin to attack the camp. At the same time, Stone ordered Colonel (of volunteers) Baker to move the 15th Massachusetts Regiment to Conrad's Ferry.

As the day developed, Devin's force, reinforced by several companies and some cavalry, became engaged with rebel infantry on the bluff. A messenger came then from Baker asking Stone whether he could move his troops forward. Stone replied that as he (Baker) was in command of that sector, he was free to do what he thought best.

As Stone explained it before the Committee on the Conduct of the War, "The whole story after that is that Colonel Baker chose to bring on a battle. He brought it on, handled the troops badly, and brought on a disaster.

Baker—no doubt excited by the idea of winning glory to himself—decided to send the entire regiment across the river. Using the boats taken from civilians along the river, the regiment very slowly crossed the river. By the time the entire regiment got across, with Baker leading them up the steep bank as he waved his sword over his head, Nathan Evans's brigade (of Bull Run fame) attacked the Union position, driving the enemy back down the bank and into the river, killing Baker in the process. By the time this happened, the Union troops—now fleeing for their lives—found no boats available at the river and plunged in and swam to save themselves.

McClellan, in his private letters to his wife, Mary Ellen, shows us the workings of an exceedingly immature mind. On the eve of the Ball's Bluff affair, he wrote her thus: "The enemy has fallen back to Centreville. My object is to force them to evacuate Leesburg."

After the disaster he wrote her this.

How weary I am of all this business! (He's hardly gotten started) Care after care, blunder after blunder, trick after trick. I am well nigh tired of the world. . . That affair of Leesburg was a horrible butchery (54 Union soldiers killed; wait until the poor devil gets to Richmond and meets the horror that is Lee). Col Baker was in command, and violated all military rules and precautions. He was outnumbered three to one and had no means of retreat. During the night, I withdrew everything and everybody to this side of the river, which, in truth, they should never have left."

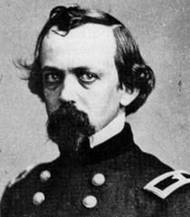

OREGON SENATOR BAKER

During the course of his testimony before the Committee on the Conduct of the War, in 1862, Stone was examined on the issue of his fraternizing with the enemy; he had honored several passes presented by ladies of Loundon County, allowing them to pass freely through his lines. Soon after this, McClellan took a report received from a "refugee" to Secretary of War Stanton. The refugee claimed that Confederate officer, Nathan Evans, proclaimed Stone a great friend of the Confederacy, and using this as the basis of excuse, Stanton summarily ordered McClellan to arrest Stone. McClellan did this, and Stone found himself thrown into prison at Fort Lafayette, in New York Harbor. He remained imprisoned for six months. Then he was released, with no charges pending, and ignored, until, briefly given a brigade to command in the seize of Petersburg. Stone resigned from the Army before the end of the war.

III

The People of Western Virginia Vote to Secede

From Virginia

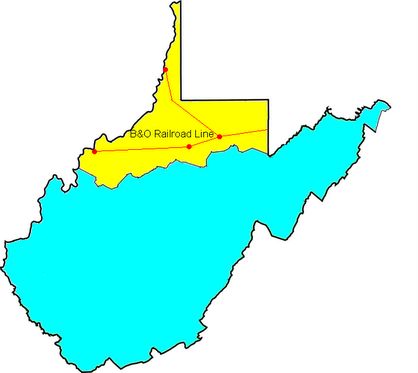

According to Charles Ambler, in his book A History of West Virginia, "There is no denying the fact that West Virginia is largely a creation of the Northern Panhandle and of counties along the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, which had supplied the officers and funds for her public institutions."

The yellow section of the map of West Virginia did, in fact, give the major portion of votes (70%) in favor of statehood. In many of the counties in the blue section of the "state" the people were against secession, induced to adopt this attitude by the Union invasion of their counties, orchestrated by McClellan and continued by his successor, William Rosecrans. These counties eventually became occupied by elements of the Union army to keep them in line.

IV

SHERMAN TAKES COMMAND

By the First of October William T. Sherman was at Louisville, in command of two brigades, preparing to move south toward Green River where Confederate general Albert S. Johnston was organizing a force to advance northward. At this time, Robert Anderson, who was in command of the Department of the Cumberland, relinquished command in the midst of a nervous breakdown, and the department command passed to Sherman by reason of seniority of rank. Sherman immediately wrote the War Department asking to be relieved. Sherman wanted to remain in command of a brigade, and Carlos Buell, then in California, was assigned to take his place.

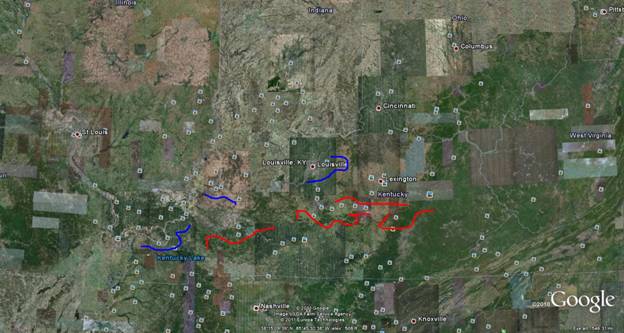

RELATIVE POSITIONS OF OPPOSING FORCES IN KENTUCKY 1861

While he waited, Sherman continued to recruit from the local population which proved not to be easy: most of the young men were inclined to the cause of the South, and the old men, with property, wanted to be left alone.

Of the military situation in Kentucky at this time, Sherman wrote after the war:

"I continued to strengthen the forward garrisons and their routes of supply; all the time expecting that Sidney Johnson, who was a real general, would unite his force and fall on one or the other. Had he done so in October, he could have walked into Louisville, and the vital part of the population would have hailed him as a deliverer. It did seem to me that the Government in Washington, intent on the larger preparations of Fremont in Missouri and McClellan in Washington, actually ignored us in Kentucky."

In the middle of the month, Simon Cameron, who had been sent by Lincoln to St. Louis to gauge the situation with Fremont, met with Sherman at Louisville as he returned east. In the conference Sherman pushed his concern that, while McClellan had 100,000 men available to cover his front of 100 miles and Fremont had 60,000 to cover a similar length of front, he had only 18,000 to cover a front of 300 miles. Sherman told Cameron that it would require 200,000 men to cover the Kentucky front. Cameron, aghast, said in response, "But where are they to come from?"

Sherman's remarks to Cameron were subsequently leaked to the Press which reported that Sherman was "insane," "crazy," "mad." Sherman responded to this, he says, "probably with language of intense feeling."

Joe Ryan