| |

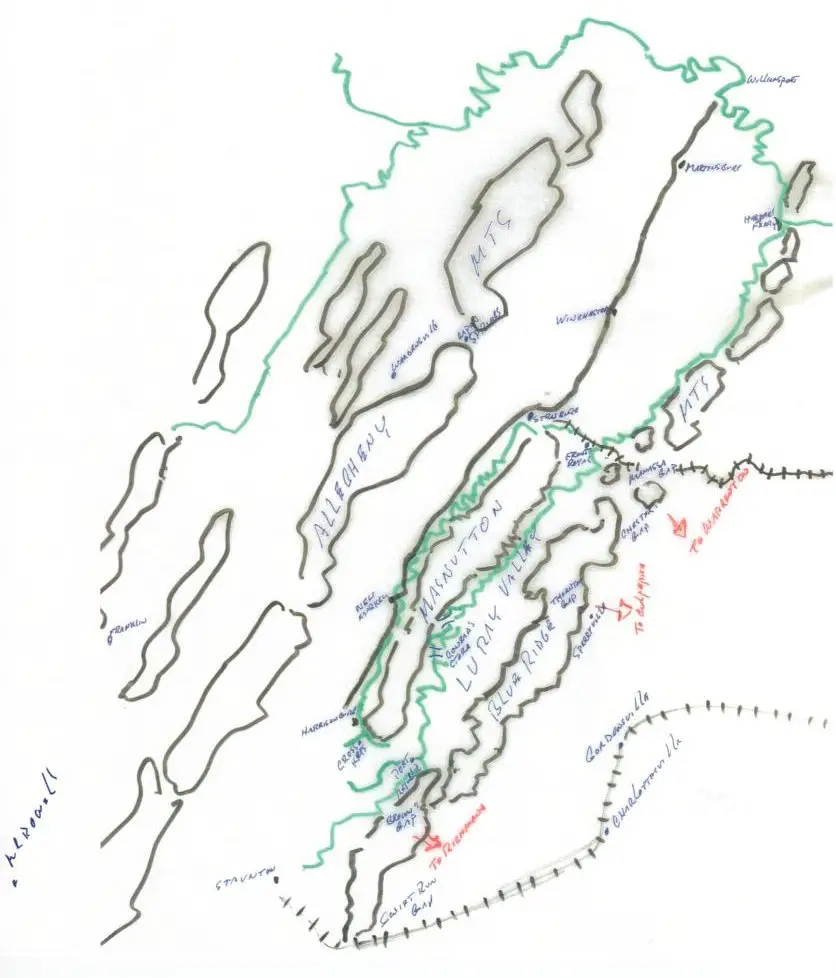

Sectors of General Lee's Operations and Topography

| |

General Lee had three choices (1) stay on the Manassas Plain after the battle of Second Bull Run (impossible by his own statement); (2) go into western Maryland, (3) fall back into the Shenandoah Valley which he eventually did. Then cross over the Blue Ridge in the vicinity of Culpeper and block McClellan's move down the east side toward Salem. Mac releived, Burnside in command, both armies moving laterally together arrive at Fredericksburg in December 1862. |

|

| |

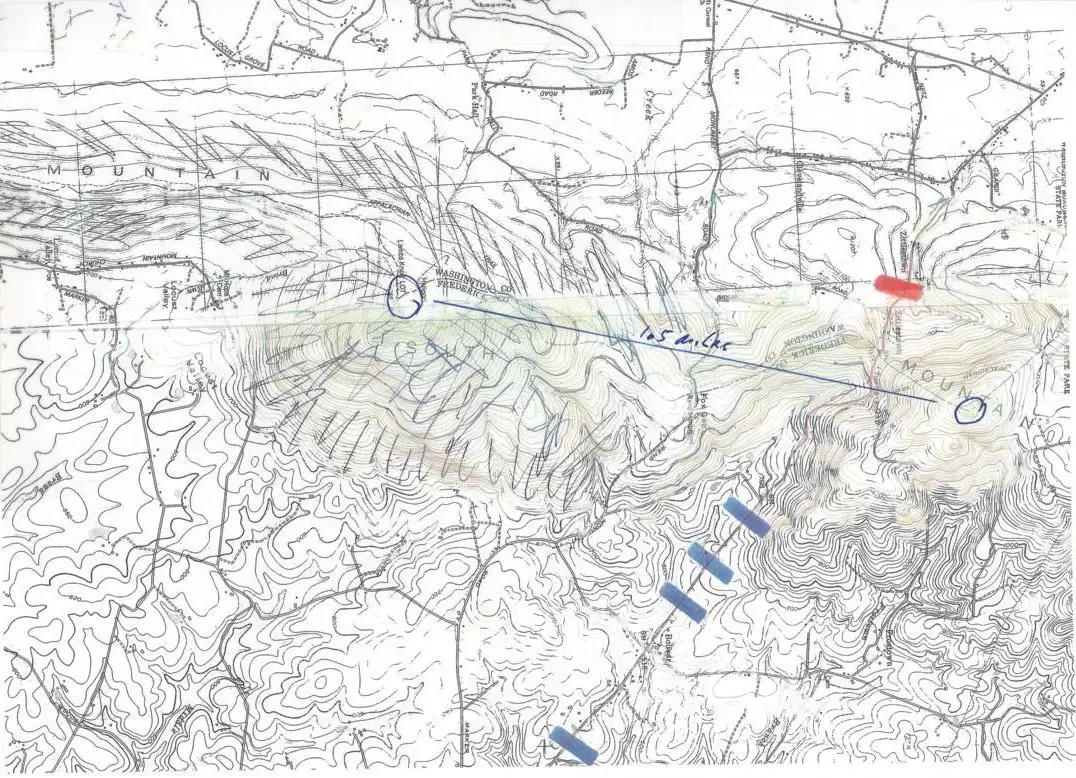

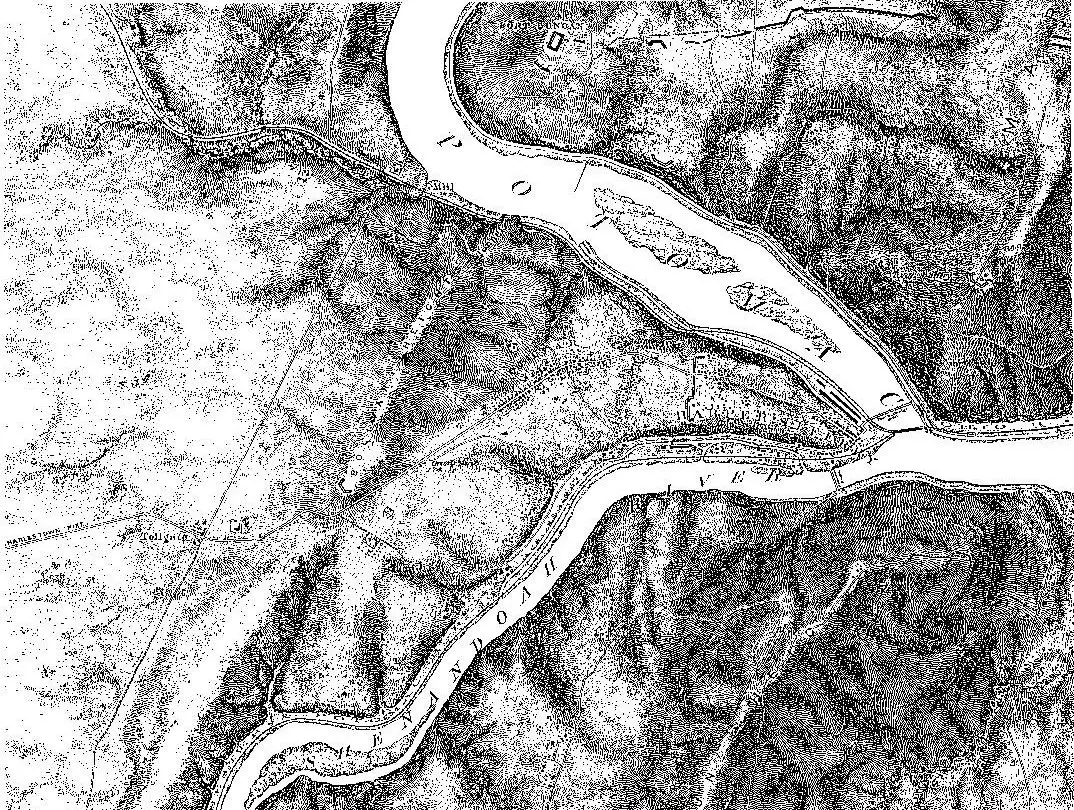

The elevations at Turner's gap reach to 1,800 feet on both sides of the National Road. When you reach the 600 foot level, the ground rises sharply, with large boulders as obstacles to your climb, the ground becoming almost vertical as you get close to the crown of the mountain. Given the text of the lost order, McClellan reasonably assumed that a force at or near the level of his force was behind the mountain at this point, poised to fall on his left flank and rear if he moved the main body of his force from Middletown toward Crampton's Gap. Therefore he decided to meet Lee's presumed force head on, leaving three divisions under William Franklin to guard his right flank and rear. Keep in mind that McClellan's own experience with Lee was limited to the encounter on the Chickahominy, where Lee threw his forces at McClellan repeatedly, apparently not concerned with the ratio between casualties suffered and success in the attacks. McClellan expected the same carnage to happen at Turner's Gap. |

|

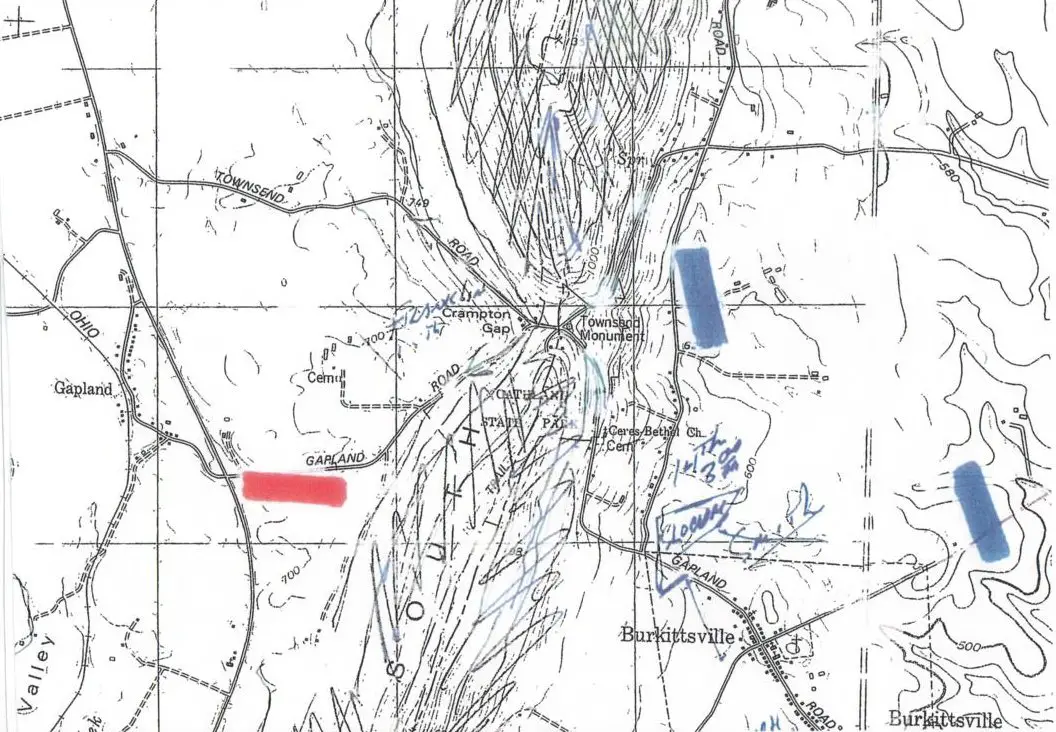

Turner Gap Topographical Map

| |

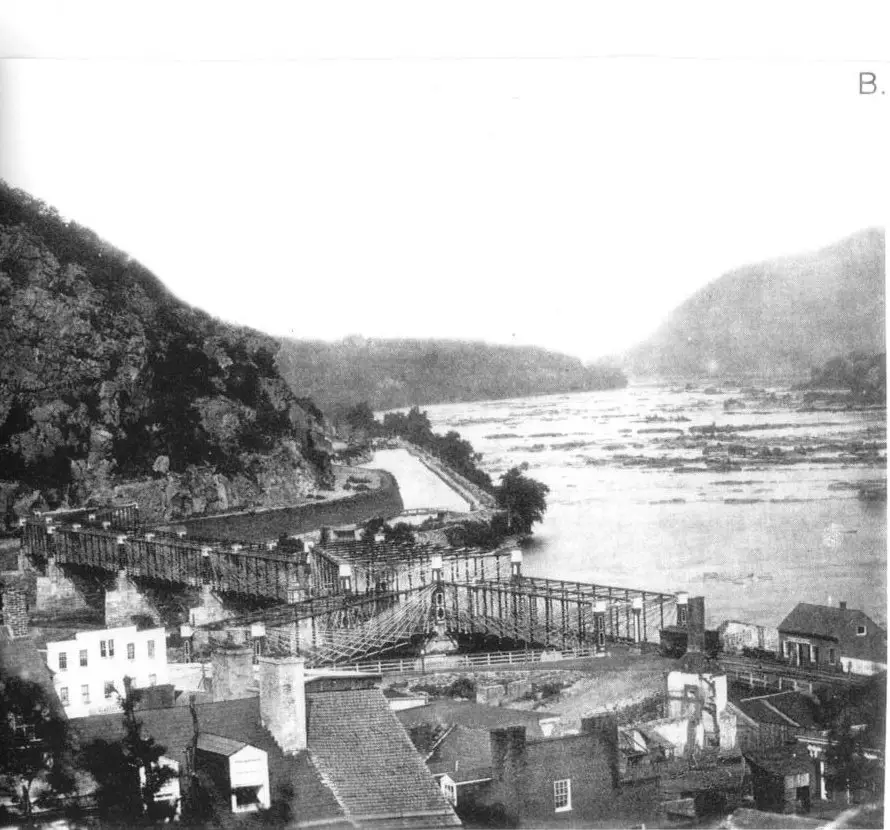

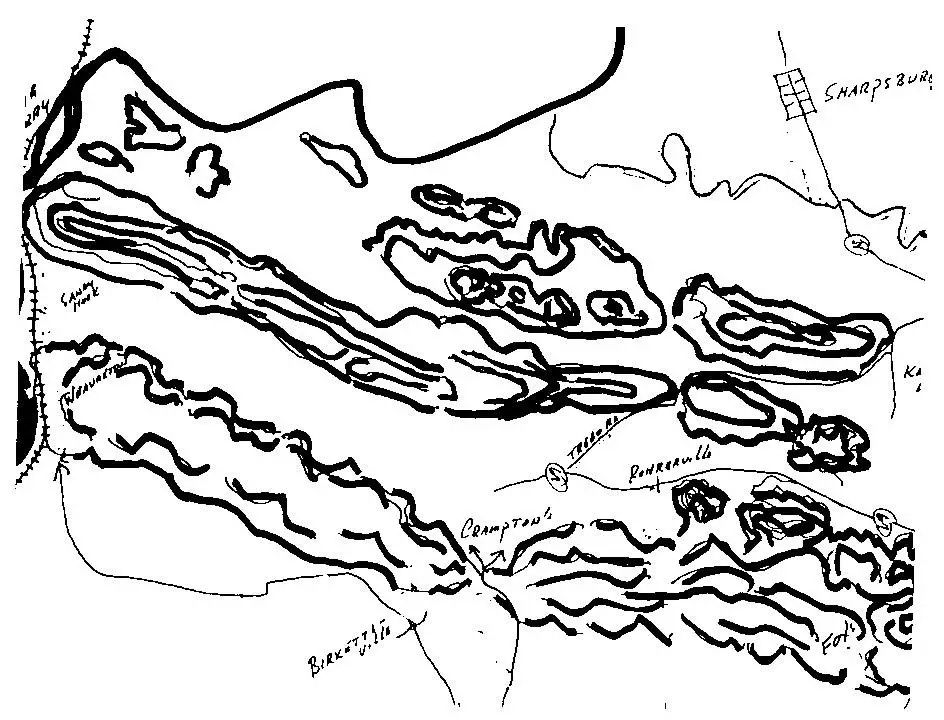

McClellan had been to Harper's Ferry. He knew the terrain on the left bank of the Potomac made it impossible for the two divisions under McLaws's command to force the surrender of the garrison at the Ferry. The best that McLaws could do with infantry is send a column around the butt of Maryland Heights, cross over the C & O canal, a formidable event in itself, reach the throat of the B & O Railroad bridge and, in mass, attempt to rush across 1,500 feet of open space, all the while from start to finish, under the fire of rifles, shells, and canister. Just an impossible task. |

|

Harpers Ferry Looking Toward Maryland Heights

view shows obstacles blocking McLaws

| |

McLaws did take possession of the crown of the mountain overlooking the Ferry, but this position gained him nothing in terms of forcing a surrender. The range of his guns could throw shells on to the toe of the peninsula, reaching as far westward as Camp Hill, but not on the Union defensive perimeter at Bolivar Heights. McLaws's real purpose was to prevent the Ferry's garrison from using the Ferry bridges to reach McClellan, just as the objective of Walker's force at Loudoun Heights was to block the garrison from moving toward Leesburg. |

|

| |

The Ferry garrison's defensive perimeter at Bolivar Heights was very strong. Because of this, Jackson was forced to consume an entire day positioning his troops for an assault, the success of which was seriously in doubt. Time was spent having Walker use the old wagon road (the bed of which still exists) to cross the crown of Loudoun Heights and get a battery of guns down on a shelf close to the Shenandoah, in order to throw shells across the river against the left end of the Union line and into its rear; this to occur as a column led by A.P. Hill tried to attack the end of the Union line through a steep ravine. |

|

| |

Why Colonel Miles at the critical moment, as Walker's shells were flying, decided to surrender without putting up resistance to Hill's momentarily expected attack will probably always be a mystery. He claimed he was out of long range shells and therefore could not repress the fire of Jackson's massed batteries along Schoolhouse Ridge. But, even if this was so, Jackson's barrage could not win the day. Jackson's infantry, taking high casualties, would have to make an assault on the scale of Malvern Hill, with the chances high that the result would be the same. Miles tried to give command to Brigadier General White who had arrived with five thousand troops from Martinsburg, but White refused. |

|

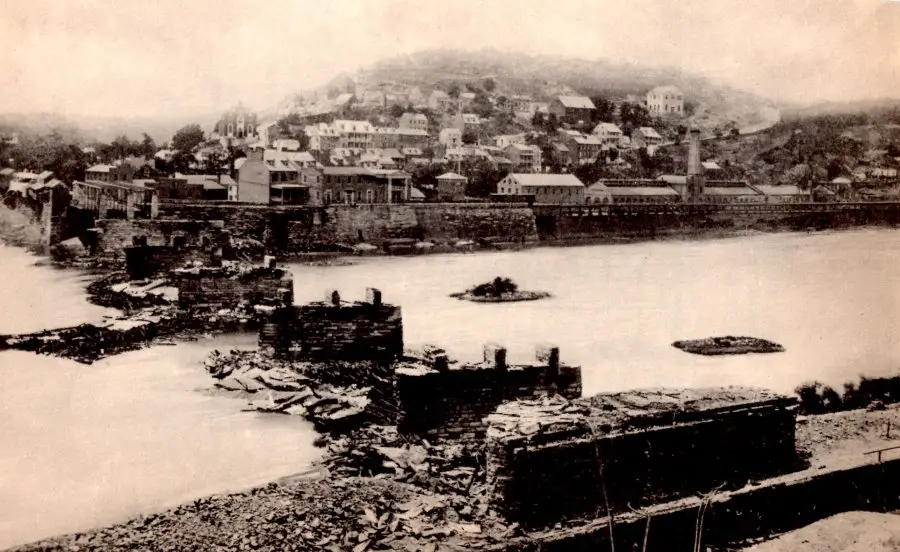

View of Harper's Ferry from the Maryland side of the Potomac

showing the destruction of the railroad bridge following Lee's Antietam Campaign

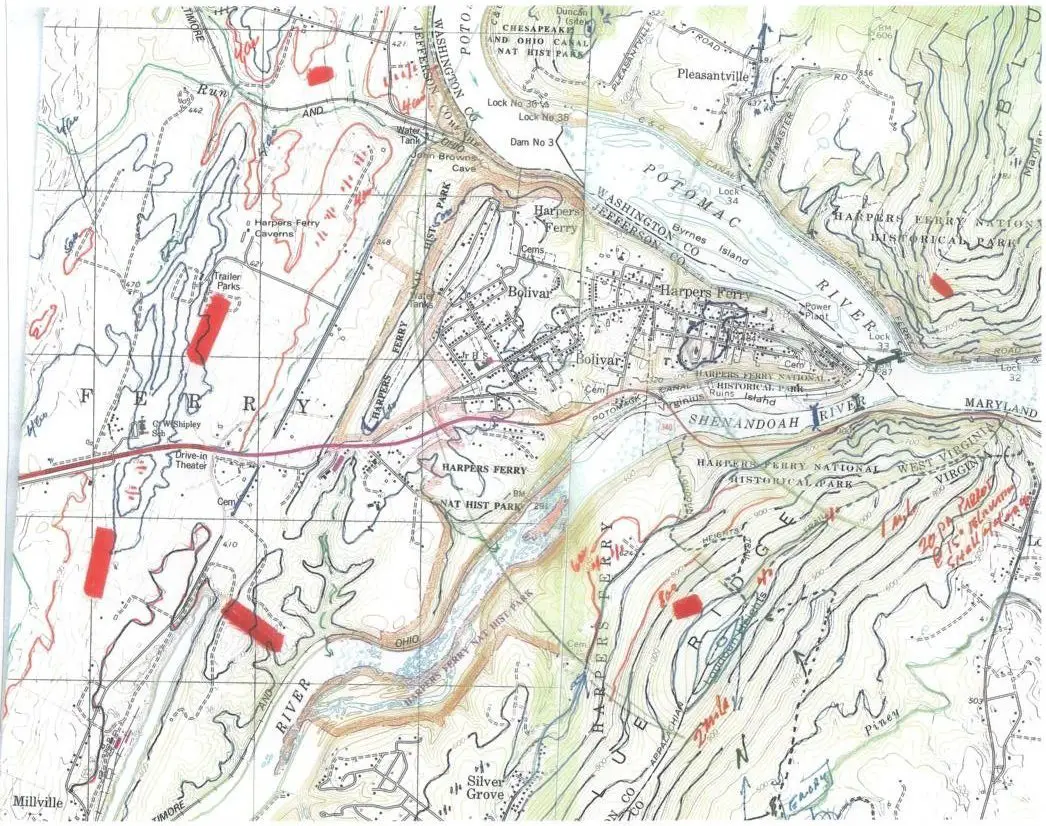

Harpers Ferry Topographical Maps

| |

On Maryland Heights today, stretching from the butt end to Solomon's Gap, the crown shows evidence of the rock fence lines thrown up as a defensive perimeter. A trail can be found leading up the mountain at the mid point and a trail leading up toward the butt end. Over the last twenty years access to these trails have become somewhat bothersome as houses have been built on lots flush up against the mountain base, the homeowners of which do not like to see trekkers swarming the trails. Still the mountain is Federal land and trekkers should not be discouraged. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

Reaching the crown of Loudoun Heights is more difficult. Though part of Shenandoah National Park, the lower slope is claimed by the descendants of the mountain folk that lived there in the 30's, the old log cabins still being maintained. Also the old road leading to the base and up and over the mountain is now claimed to be a private road. Once you gain the slope, however, following a current topo map, you should be able to reach the old wagon road and follow it (the dotted line) over the crown and down to the Shenandoah. |

|

A fragment of a Union topographical map: it shows faint lines which indicate the existing road net over Loudoun and Maryland Heights.

| |

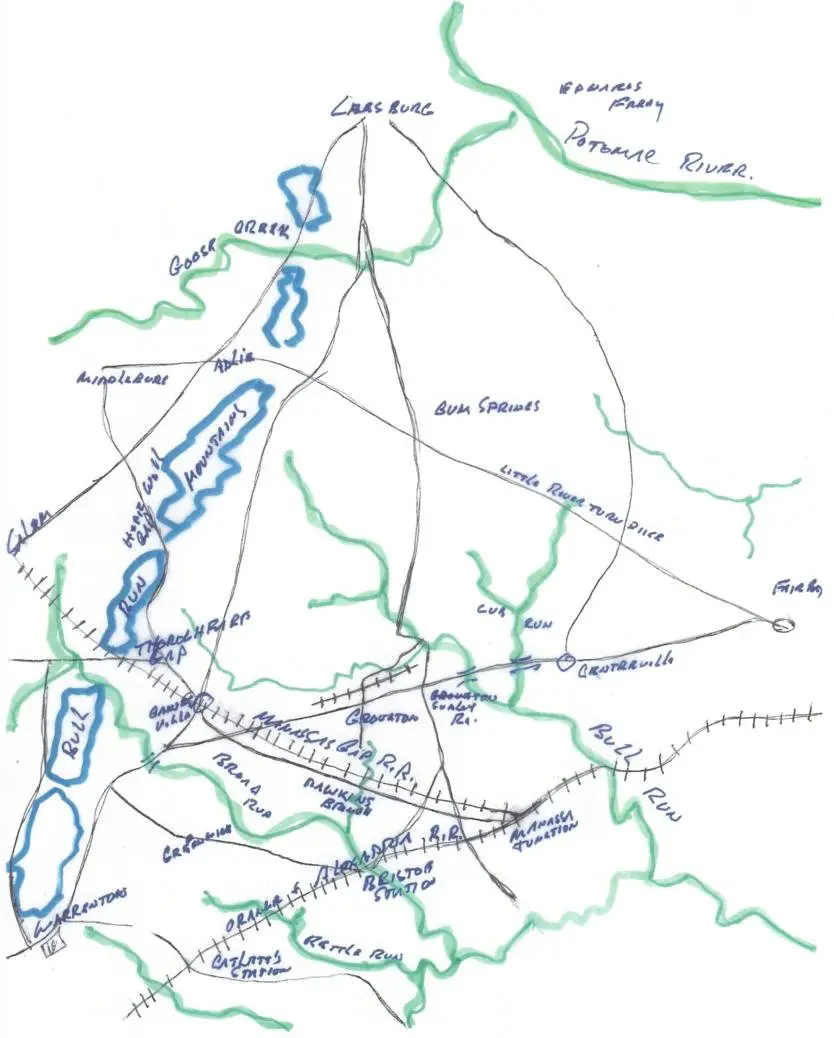

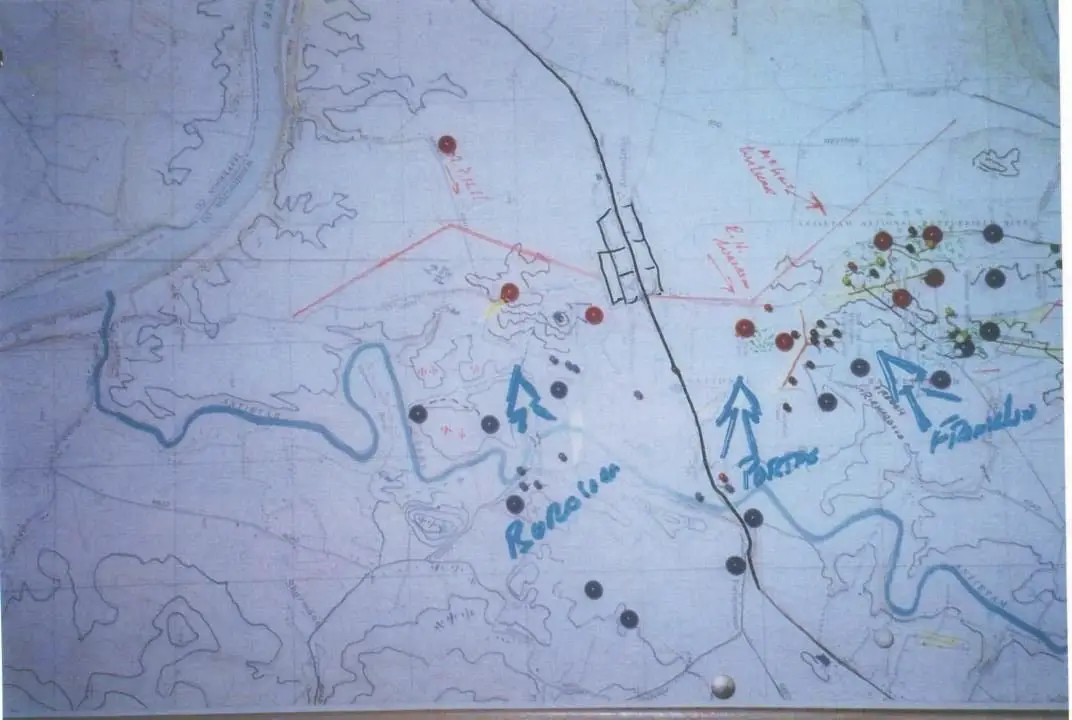

This view of Pleasant Valley shows the difficulty General Lee's force would have faced, had it been required to block Mac's force from occupying the valley. Lee could have gotten at Mac's right flank inside the valley only by sending columns toward Rohrersville. Mac could easily hold his right flank from such an attack while swiftly moving columns to seize Maryland Heights and the Harper's Ferry bridges thereby opening communication with the garrison and thwarting any reasonable chance that Jackson might seize the garrison. At the same time, though, the terrain at the head of the valley at Rohrersville would have given Lee protection as he moved his force away from McClellan's and toward the Potomac. Everything depended on how Mac reacted to the text of the lost order. |

|

Pleasant Valley

| |

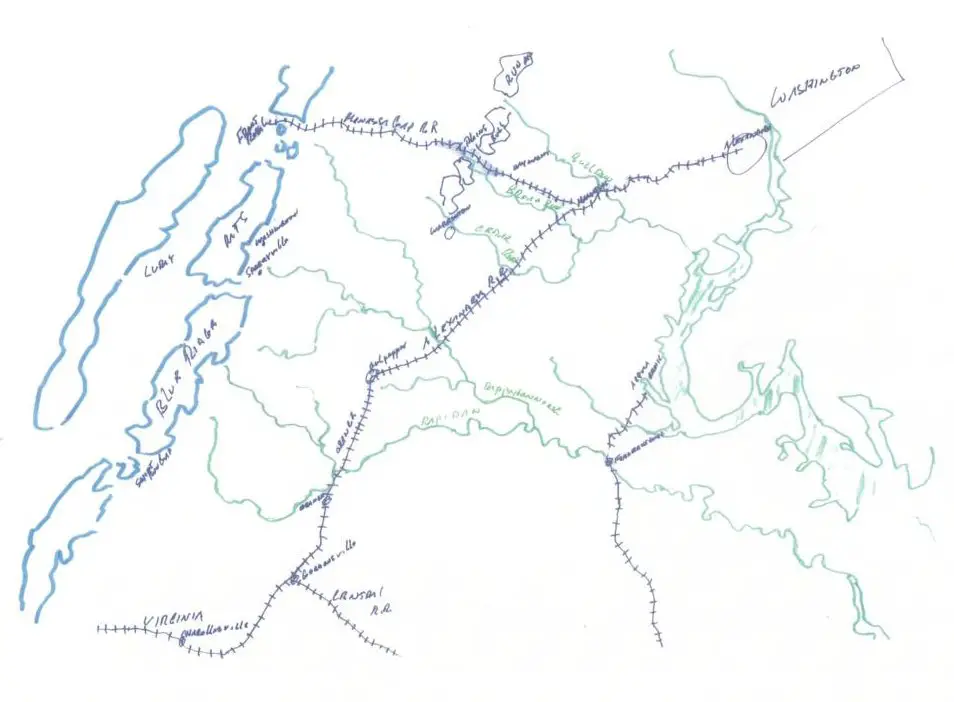

In August/September 1862, the Confederate government's supply system was paralyzed, unable to logistically support General Lee in his advanced position on the Manassas Plain. The Orange & Alexandria Railroad, as well as the Virginia Central, was a one track road. Even if Richmond had sufficient supplies to feed Lee's army, the daily effort to get the supplies forward by trains over almost eighty miles of track was beyond the capacity of the railroads to absorb. This fundamental fact of an army's survival General Lee could not ignore. It made it impossible for him to maintain his army on the Manassas Plain. The consequence of this hard fact of reality was that he had to move his army to the Shenandoah Valley, the only place south of the Potomac where there was an abundance of food for his men, grain and forage for his animals. It should not take a rocket engineer to recognize that Lee could not take his army there directly. So he decided upon the indirect approach, a concept of military maneuver invented by Napoleon. |

|

Northern Virginia Railroad Network

| |

These are the roads that existed in 1862 and which General Lee intended to use as he began moving north toward the Rappahannock, after Pope's withdrawal from the Rapidan. Lee had in view from the beginning of the operation, heading for Maryland via Leesburg. Through the entire month of August, the front of his army kept slowly moving in that direction.

What was to happen along the way, depended upon how efficient the Union command structure was in rapidly bringing together McClellan's army with Pope's. As Lee got abreast Warrenton, on August 23-24, the intelligence he was receiving told him that it was highly unlikely that, over the next several days, Pope would be strengthened by the weight of McClellan's army. Therefore, always thinking attack, Lee decided on the plan which sent Jackson to Manassas Junction to destroy Pope's base of operations.

Once this happened and it was clear there were still several days before Pope was made too big to fight, Lee decided to leave Jackson in a defensive position, to receive Pope's attack, while Lee moved up. Because of the dysfunctional nature of Pope's command structure, and a fatal tactical error Pope made on the second day of the battle with Jackson (removing Porter's corps from Dawkin's Branch), Lee was able to throw his force against Pope's left wing and force Pope back a half mile to the bank of Bull Run; with Pope's retreat to Centerville, then Fairfax and his collapse of will, the stage was set for Lee to continue moving toward Maryland. At any time during his operations against Pope on the Manassas Plain Lee could have disengaged and moved away on the roads toward Leesburg, Jackson acting as rear guard. |

|

Road Net Manassas Plain

| |

This sector was Lee's goal from the moment he left the Rapidan: the lower valley with Winchester as his base of operations, drawing his supplies from the countryside, leaving Richmond to wagon him his ammunition via Culpeper and Staunton. From this position, if pressured, he could move up the valley toward Staunton, or cross the Blue Ridge and head back to the Rappahannock or Rapidan.

The text of the lost order told McClellan that Jackson's command was to move via Shepherdstown ford directly to Martinsburg where he was to stop and wait for refugees fleeing from the Ferry. But Lee had no intention of Jackson doing it that way. Instead of approaching Martinsburg from the northeast, allowing the garrison there to fall back toward the western mountains, Jackson had to make a roundabout march, via Williamsport, pushing the garrison under White eastward toward the Ferry. This roundabout march Lee knew would require an additional twenty four hours to accomplish. Giving Mac, if he had divined it, plenty of time to beat Jackson to the Ferry. |

|

Shenandoah Valley

| |

The elevations at Crampton's Gap are half as much as those at Turner's. The gap itself is a low saddle between two 600 foot hills, with several logging roads, cart tracks etc honeycombing the hills. Had McClellan thrown the main body of his force toward this gap on the 14th, Lee would not have been able to prevent him from quickly penetrating the gap, taking possession of Rohrersville and Pleasant Valley and moving columns toward Sharpsburg and the Harper's Ferry bridges. Not only could McClellan easily penetrate the gap directly, but also he could move a column down toward Weaversville, cross one column over the mountain at Brownsville and have another one come around the butt end of the mountain to occupy Sandy Hook. If this had been done, Lee would have had no reasonable choice but to move his force across the Potomac by Sheperdstown ford, Falling Waters, or Williamsport. At that point the theater of operations for both armies would have shifted to the lower Shenandoah Valley.. |

|

Crampton Gap Topographical Map

| |

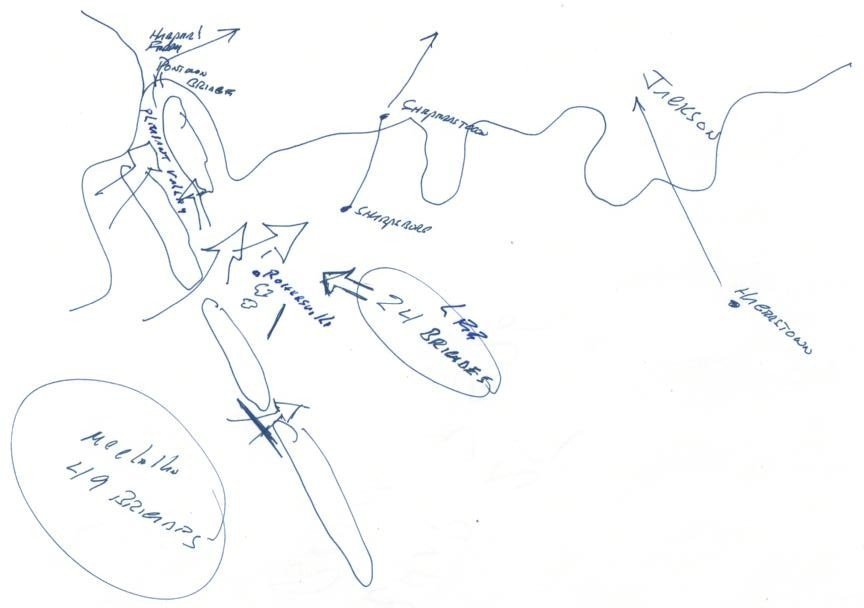

After detaching the forces sent to Maryland Heights and across the Potomac, the force left with Lee was reduced to 24 brigades, less than half the force available to McClellan. If McClellan had moved toward Harper's Ferry, the best that Lee could have accomplished with his force was to hold a defensive position in front of Rohersville as his columns, wagon and ammunition trains included, moved toward Sheperdstown ford and Williamsport. There would have been no chance that Jackson would have time to force the surrender of the garrison at the ferry. |

|

Crampton Gap Relative Forces

| |

By the time McClellan had gained possession of Turner's Gap on the morning of the 15th, Colonel Miles had surrendered the Ferry. Mac spent the 15th getting the main body of his army over the South Mountain and on the 16th followed Lee to the Antietam. By mid-afternoon on the 17th Lee's left and center were on the cusp of being overrun, and Mac ordered a concerted fresh attack using the 9th Corps on the left, Porter's corps in the center and Franklin's corps on the left. But then, his key commanders vacillating, he thought about his two divisions that were not yet up and changed his mind. Only Burnside's attack went forward on the left and Lee met it with his last reserve, A.P. Hill's Light Division. On the 18th, with Couch's and Humphrey's now up, Mac stood on the defensive, his organization wrecked.

The next day Lee stepped into the Valley where he remained unmolested for six weeks. He had moved his army 120 miles in thirty days, from Richmond to Frederick to Sharpsburg to the valley, fighting three battles along the way, clearing Virginia of Lincoln's invading armies. |

|

|

|