|

|

|

|

Voice of Freedom A Story About Frederick Douglass Interesting for both children and adults . |

We, the colored soldiers, have fairly won our rights by loyalty and bravery -- shall we obtain them?

If we are refused now, we shall demand them. ...Sargent Major William McCeslin; 29th U.S.C.T.

Serving the Union: U.S. Colored Troops in the Retreat to AppomattoxThe union armies under Lt. General Ulysses S. Grant would sever Confederate General Robert E. Lee's supply line to Petersburg on April 2, 1865. Lee would be forced to evacuate the Confederate Capital of Richmond and the fortified supply center of Petersburg thus beginning his final campaign of the war. While most of the United States Colored Troops in the Federal Army were involved with the occupation of Richmond on the morning of April 3rd, some did enter Petersburg when it fell on the same day. Brigadeer General William Birney's second division, XXV Corps, operating south of the Appomattox River, would be among the first units to come into the city from the west. It was noted that the 7th U.S.C.T. regiment, recruited in Maryland, and the 8th U.S.C.T., from Philadelphia, were on the skirmish line that morning and with those who marched into the evacuated railroad center. The 7th's commander, Lt. Colonel Oscar E. Pratt, wrote, "I entered the city of Petersburg at 6 a.m., amidst the joyous acclamations of its sable citizens." There were seven Black units (approximately 2,000 men, or 3% of the Federal force) which made the journey all the way to Appomattox Court House with Major General Edward Ord's Union Army of the James and arrived in time to be involved in the final fighting. On their wat they passed through the settlements of Blacks & Whites, Nottoway Court House, Burkeville Junction, Rice's Station, and Farmville. From the latter point they stayed south of the Appomattox River and traveled via Walker's Church (present day Hixburg) to Appomattox. These regiments were of Colonel William W. Woodward's brigade, the 29th and 31st U.S.C.T., along with the 116th U.S.C.T., assigned to them from another brigade. Colonel Ulysses Doubleday's brigade, 8th, 41st, 45th, and 127th U.S.C.T., were also present. The first brigade, under Colonel James Shaw, Jr., would not arrive until the day after the surrender, having march ninety-six miles in four days. His brigade was detached from the others and sent back to Sutherland Station for a period of time, causing their delay. On the morning of the 9th at Appomattox Court House, the Black units were sent forward to support other Federal units in the closing phase of the battle. Consequently, only Woodward's brigade participated in the final advance on the Confederate line. Some of Doubleday's skirmishers did proceed forward, and the only casualty for the U.S.C.T. brigades was Captain John W. Falconer of Company A, 41st U.S.C.T., a white officer. He was mortally wounded and died on April 23rd. According to Surgeon-in-Chief Charles P. Heinchhold, during the entire campaign, the U.S.C.T.'s lost 4 men killed, 1 officer (mortally) and 30 men wounded, a total of 35 casualties. |

Kindle Available Black Slaveowners: Free Black Slave Masters in South Carolina, 1790-1860 An analysis of all aspects and particularly of the commercialism of black slaveowning debunks the myth that black slaveholding was a benevolent institution based on kinship, and explains the transition of black masters from slavery to paid labor. |

Banner of the Third U.S. Colored Troops African-American Regiment in the Civil War 12 in. x 9 in. Buy at AllPosters.com Framed Mounted |

Black Soldiers Along the Rio Grande Colored Troops Reading Titles |

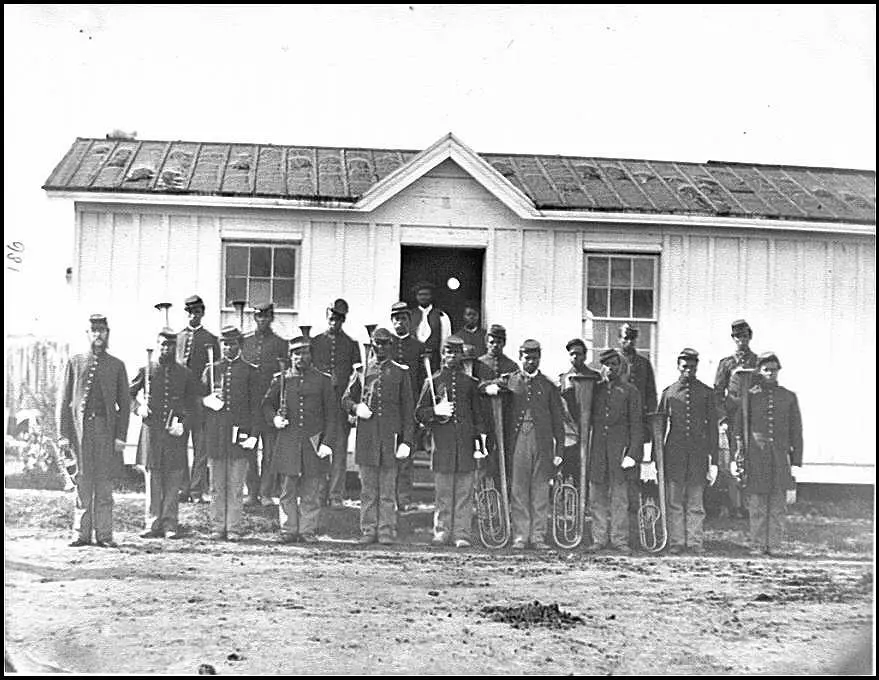

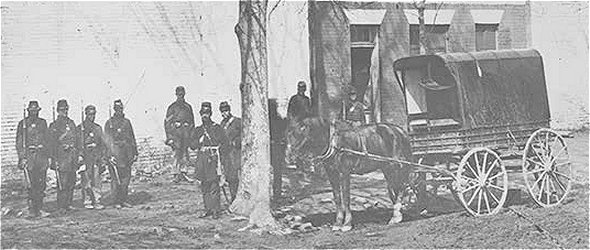

Click to enlarge Arlington, Virginia Band of 107th U.S. Colored Infantry at Fort Corcoran |

|

A must-read for American and African American history classes |

|

Honor in Command: Lt. Freeman S. Bowley's Civil War Service in the 30th United States Colored Infantry  Black Southerners in Confederate Armies Official records, newspaper articles, and veterans' accounts to tell the stories of the Black Confederates. This well researched collection is a contribution to the discussion about the numbers of black Southerners involved and their significant history. |

Serving the ConfederacyWith General Robert E. Lee's manpower reserves quickly draining, on March 23, 1865, General Orders #14 was issued which allowed for the enlistment of Blacks into the Confederate service. Shortly thereafter, a notice was posted in Petersburg's The Daily Express, "The commanding General deems the prompt organization of as large a force of negroes as can be spared, a measure of the utmost importance, and the support and co-operation of the citizens of Petersburg and the surrounding counties is requested by him for the prosecution to success of a scheme which he believes promises so great benefit to our cause...To the slaves is offered freedom and undisturbed residence at their old homes in the Confederacy after the war. Not the freedom of sufferance, but honorable and self won by the gallantry and devotion which grateful countrymen will never cease to reward." The recruitment effort did bear fruit in Richmond where Majors James W. Pegram and Thomas P. Turner put together a "Negro Brigade" of Confederate States Colored Troops. The Richmond Daily Examiner noted of the unit "the knowledge of the military art they already exhibit was something remarkable. They moved with evident pride and satisfaction to themselves." As the Confederate army abandoned Richmond on April 3rd, apparently these Black Confederate soldiers went along with General Custis Lee's wagon train on its journey. They would move unmolested until they reached the area of Painesville on April 5. Here they were attacked by General Henry Davies' cavalry troopers. A Confederate officer, who rode upon this situation as it was transpiring, recalled: "Several engineer officers were superintending the construction of a line of rude breastworks...Ten or twelve negroes were engaged in the task of pulling down a rail fence; as many more occupied in carrying the rails, one at a time, and several were busy throwing up the dirt...The [Blacks] thus employed all wore good gray uniforms and I was informed that they belonged to the only company of colored troops in the Confederate service, having been enlisted by Major Turner in Richmond. Their muskets were stacked, and it was evident that they regarded their present employment in no very favorable light." On April 10th, as Confederate prisoners were being marched from Sailor's Creek and elsewhere to City Point (present day Hopewell) and eventually off to Northern prison camps, a Union chaplain observed the column. This incident along the retreat to Painesville, seems to be the only documented episode of "official" Black troops serving the Confederacy in Virginia as a unit under fire. African-Americans also accompanied the Confederate army on the retreat with the First Regiment Engineer Troops and provided yeoman service. One member of this unit remembered that they mounded roads, repaired bridges and cut new parallel roads to old ones when they became impassable. When this was not possible, an engineer officer would post a group near the trouble spot to extricate wagons and artillery pieces. When Lee surrendered his army at Appomattox, thirty-six African-Americans were listed on the Confederate paroles. Most were either servants, free blacks, musicians, cooks, teamsters or blacksmiths. A Black woman was to become the only civilian casualty in the final fighting at Appomattox. Hannah stayed behind with her husband in the home of Doctor Coleman located on the battlefield and was mortally wounded by an artillery round. A Union chaplain remembered: "she was sick with fever and unable to be moved. As she lay upon her bed, a solid shot had passed through one wall of the house at just the right height to strike her arm, and then passed out through the opposite wall |

Black Confederates and Afro-Yankees in Civil War Virginia African American life in Virginia, both slave and free, during the civil war, from soldiers who fought in the Confederate and Union armies to those who acted as spies |

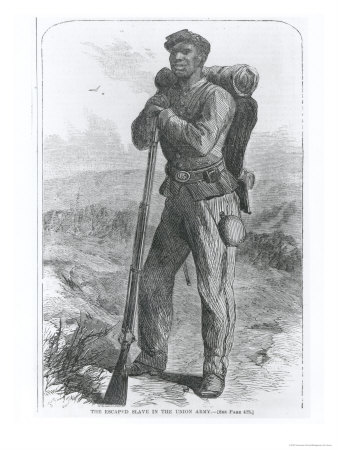

The Escaped Slave in the Union Army from "Harper's Weekly", 1864 18 in. x 24 in. Buy at AllPosters.com Framed Mounted |

DVD  Race to Freedom: The Story of the Underground Railroad Kindle Available  A Slave No More: Two Men Who Escaped to Freedom, Including Their Own Narratives of Emancipation |

Camp of the Tennessee Colored Battery

|

Slaves No More: Three Essays on Emancipation and the Civil War The first essay traces the destruction of slavery by discussing the shift from a war for the Union to a war against slavery The second essay examines the evolution of freedom in occupied areas of the lower and upper South. The third essay demonstrates how the enlistment and military service of nearly 200,000 slaves hastened the transformation of the war into a struggle for universal liberty Kindle Available  Ar'n't I a Woman?: Female Slaves in the Plantation South Firsthand accounts of Black "sisters of the spirit" is the only way to truly gain a feel for what they endured and the larger cultural evils. |

Where Death and Glory Meet: Colonel Robert Gould Shaw and the 54th Massachusetts Infantry July 18, 1863, the African American soldiers of the Fifty-Fourth Massachusetts Infantry led a courageous but ill-fated charge on Fort Wagner, a key bastion guarding Charleston harbor. Confederate defenders killed, wounded, or made prisoners of half the regiment. Only hours later, the body of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, the regiment's white commander, was thrown into a mass grave with those of twenty of his men. |

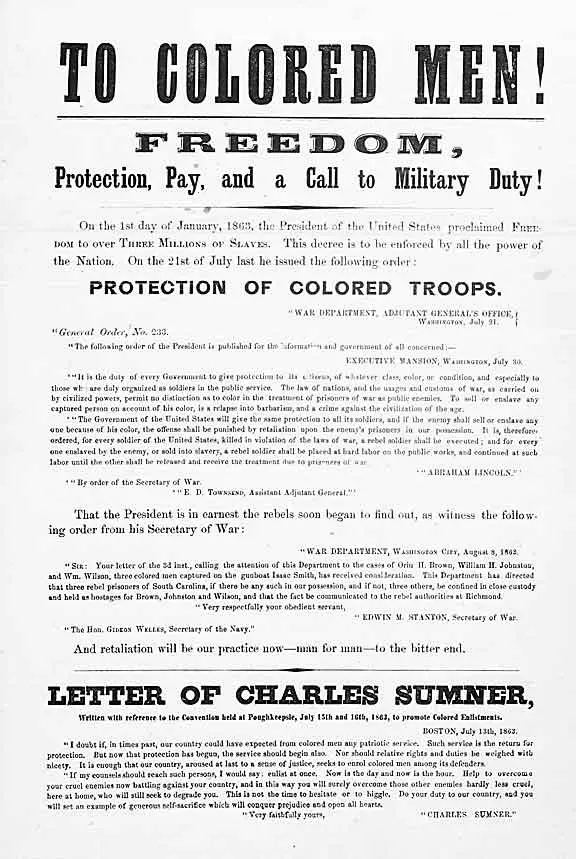

Click to Enlarge Recruiting Poster  |

When Slavery was Called Freedom: Evangelicalism, Proslavery, and the Causes of the Civil War dissects the evangelical defense of slavery at the heart of the nineteenth century's sectional crisis. John Patrick Daly's writing uncovers the cultural and ideological bonds linking the combatants in the Civil War era and boldly reinterprets the intellectual foundations of secession |

Two months after the tragic Petersburg episode, black soldiers displayed their worth at the Battle of New Market Heights (Chaffin's Farm) near Richmond on September 29, 1864. Fourteen men, including Christian Fleetwood, who later became an active community leader in Washington, D.C. were presented the Medal of Honor for valor at New Market Heights. Several were awarded to men who took charge of their units after all white commanders had fallen. Soldiers of distinction were also given the Army of the James or "Butler" medal, designated by champion of the black troops, Gen. Benjamin Butler and the only medal created solely for the U.S.C.T. |

Colored Troops Medal of Honor Winners

|

Kindle Available Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America The evolution of black society from the first arrivals in the early seventeenth century through the Revolution |

Kindle Available The Missouri Compromise and Its Aftermath: Slavery and the Meaning of America Go behind the scenes of the crucial Missouri Compromise, the most important sectional crisis before the Civil War, the high-level deal-making, diplomacy, and deception that defused the crisis. |

Reconstruction after the Civil War Chicago History of US Civilization Praised for cutting through the controversial scholarship and popular myths of the time to provide an accurate account of the role of former slaves during this period in American history |

Kindle Available Nothing but Freedom Emancipation and Its Legacy Insights into the relatively neglected debates over fencing laws and hunting and fishing rights in the postemancipation South, and into the solidarity of the low-country black community |

Slavery, Secession, and Civil War Views from the UK and Europe, 1856-1865 Contains articles written by foreign journalists living in the UK and Europe during the American Civil War, who provide an outsider's view of events. Articles were first published from 1856-1865 in British, French, and Spanish journals |

Bitter Fruits Of Bondage: The Demise Of Slavery And The Collapse Of The Confederacy, 1861-1865 The process of social change initiated during the birth of Confederate nationalism undermined the social and cultural foundations of the southern way of life built on slavery, igniting class conflict that ultimately sapped white southerners of the will to go on. |

Prelude to Civil War: The Nullification Controversy in South Carolina From 1816 to 1836 planters of the Palmetto State tumbled from a contented and prosperous life to a world rife with economic distress, guilt over slavery, and apprehension of slave rebellion. Compelling details ofhow this reversal of fortune led the political leaders down the path to states rights doctrines |

A House Divided: The Antebellum Slavery Debates in America, 1776-1865 An excellent overview of the antebellum slavery debate and its key issues and participants. The most important abolitionist and proslavery documents written in the United States between the American Revolution and the Civil War |

To 'Joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women's Lives and Labors after the Civil War Thousands of former slaves flocked to southern cities in search of work, they found the demands placed on them as wage-earners disturbingly similar to those they had faced as slaves: seven-day workweeks, endless labor, and poor treatment |

Kindle Available Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America The evolution of black society from the first arrivals in the early seventeenth century through the Revolution |

Kindle Available Political Culture and Secession in Mississippi: Masculinity, Honor, and the Antiparty Tradition, 1830-1860 A rich new perspective on the events leading up to the Civil War and will prove an invaluable tool for understanding the central crisis in American politics. |

Kindle Available Nothing but Freedom Emancipation and Its Legacy Insights into the relatively neglected debates over fencing laws and hunting and fishing rights in the postemancipation South, and into the solidarity of the low-country black community |

Strike the Blow for Freedom: The 6th United States Colored Infantry in the Civil War The recruitment, training, battles and finally the mustering out of the 6th. The 6th shared some of the same influences that shaped the formation of many military units of that time |

Kindle Available The Negro's Civil War: How American Blacks Felt and Acted During the War for the Union In this classic study, Pulitzer Prize-winning author James M. McPherson deftly narrates the experience of blacks--former slaves and soldiers, preachers, visionaries, doctors, intellectuals, and common people--during the Civil War |

Slaves without Masters The Free Negro in the Antebellum South The moving story of the quarter of a million free black men and women who lived in the South before the Civil War. portraying their struggle for community, economic independence, and education within an oppressive society. |

Black Confederates It was illegal for Blacks to carry arms until March of 1865, and numerous Confederate Government documents attest to the illegality of using slaves and free Blacks in that capacity |

|

Turn Homeward, Hannalee During the closing days of the Civil War, plucky 12-year-old Hannalee Reed, sent north to work in a Yankee mill, struggles to return to the family she left behind in war-torn Georgia. "A fast-moving novel based upon an actual historical incident with a spunky heroine and fine historical detail."--School Library Journal. |

My Brothers Keeper Virginia Dickens is angry. Her father and brother Jed have left her behind while they go off to Uncle Jack's farm to help him hide his horses from Confederate raiders. It's the summer of 1863 and Pa and Jed believe 9-year-old Virginia will be out of harm's way in the sleepy little town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. |

Kindle Available I Thought My Soul Would Rise and Fly: The Diary of Patsy, a Freed Girl, Mars Bluff, South Carolina 1865 Not only is 12-year-old Patsy a slave, but she's also one of the least important slaves, since she stutters and walks with a limp. So when the war ends and she's given her freedom, Patsy is naturally curious and afraid of what her future will hold. |

Numbering The Bones The Civil War is at an end, but for thirteen-year-old Eulinda, it is no time to rejoice. Her younger brother Zeke was sold away, her older brother Neddy joined the Northern war effort,. With the help of Clara Barton, the eventual founder of the Red Cross, Eulinda must find a way to let go of the skeletons from her past. |

|

Books Civil War Womens Subjects Young Readers Military History DVDs Confederate Store Civil War Games Music CDs Reenactors |