| Read all the Civil War Sesquicentennial articles | Comments and Questions to the Author |

| A Trial Lawers Notebook | |

| President Lincoln’s War Fleet | |

| What If New York State Had Seceded |

I

President Lincoln Dupes The Confederates into Firing on Sumter ©

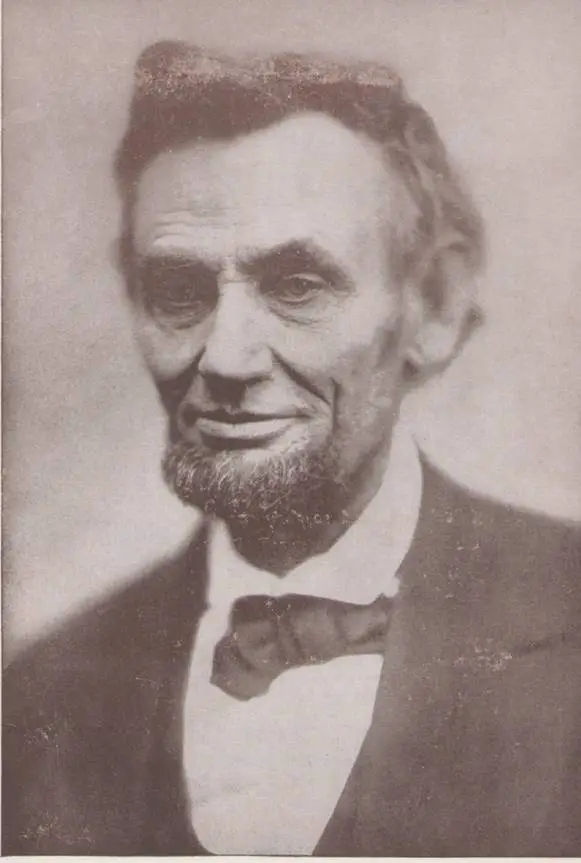

On Monday, April 1, 1861, Abraham Lincoln decided how he would deal with the problem of Fort Sumter. It was plain that an attempt to enter Charleston Harbor with military force would be recognized the world over as an act of hostility by the United States against South Carolina, that the State would be privileged under the laws of war to resist. It was exactly this outcome that William H. Seward had been adament in arguing, over the last two weeks, Lincoln should avoid.

Just three days earlier, at a Cabinet meeting, Seward’s policy seemed to be accepted, when General Scott formally opined that both Fort Sumter and Fort Pickens be evacuated. Backing Scott up, Seward had stressed the point that the dispatch of an expedition to Charleston “would provoke an attack and so involve war at that point.” Seward had tried to bloster his case with the concession that, while Sumter should be evacuated, Pickens should be held— suggesting that Captain M.C. Meigs could organize an expedition to relieve Pickens.

Lincoln responded, by giving Seward the choice of either having the expedition to Charleston result in a collision of arms, as Lincoln already had Gustavus V. Fox organizing it, or help Lincoln derail it without any one knowing.

Executive Mansion, April 1, 1861

William H. Seward

My dear Sir: Upon your propositions, you say that whatever policy we adopt either the President must energetically prosecute it or delegate it to some member of his cabinet such as you. I remark that if this must be done, I must do it. When a general line of policy is adopted, I want no unncessary debate.

Your Obt Servt. A. Lincoln

Accepting the fact he could not move Lincoln to his view, Seward agreed to participate. Working hand-in-hand now with Seward, Lincoln wrote the following messages on Monday, April 1.

No originals of these messages have come down to us. There are more than one version of some of them, written by different persons. None of the messages in the record are in Lincoln’s hand, but their essential accuracy is confirmed by David D. Porter who received them from Lincoln’s hand and carried them to New York. (Porter does not tell us what he did with the order addressed to him.)

Executive Mansion, April 1, 1861

Commandant Andrew H. Foote, commanding Brooklyn Navy Yard

Sir: You will fit out the Powhatan without delay. Lieutenant Porter will relieve Captain Mercer in command of her. She is bound for secret service, and you will under no circumstances communicate to the Navy Department the fact that she is putting out.

Abraham Lincoln

Executive Mansion, April 1, 1861

Captain Samuel Mercer, U.S. Navy

Sir: Circumstances render it necessary to place in command of your ship, and for a special purpose, an officer who is duly informed and instructed in relation to the wishes of the Government, and you will therefore consider yourself detached.

Abraham Lincoln

Executive Mansion, April 1, 1861

Lieutenant David D. Porter

Sir: You will proceed to New York, and with the least possible delay assume command of the Powhatan. Proceed to Pensacola Harbor, and at any cost prevent any Confederate expedition from the mainland reaching Fort Pickens. This order, its object, and your destination will be communicated to no person whatever until you reach the harbor of Pensacola.

Abraham Lincoln

New York Times, April 1, 1861

There are four percipiant witnesses who have left accounts in the historical record of what happened next. First, Gideon Wells:

On Friday, March 29, Welles had received this message from Lincoln.

Executive Mansion, (Friday) March 29, 1861

Hon Secretary of the Navy

Sir: I desire an expedition, to move by sea, be got ready to sail as early as April 6, the whole according to memorandum attached; and that you cooperate with the Secretary of War for that object.

Your Obt Servt. A. Lincoln.

Navy Department

Steamers Pocahontas at Norfolk, Pawnee at Washington, and Harriet Lane at New York to be ready (under sailing orders) for sea.

War Department

Two hundred men at New York ready to leave garrison. Supplies for twelve months for two hundred men ready for instant shipping. A large steamer and three tugs engaged.

In a book published by his son after his death, these words are put in Welles’s mouth: “Mr. Gustavus V. Fox visited Fort Sumter, (on March 23rd) and saw Major Anderson, and was confident he could reinforce the garrison. The President determined to accept the volunteer services of Mr. Fox. The transports which the War Department was to charter were to rendezvous off Charleston Harbor with the naval (war) vessels, which would act as convoy, and render such assistance as would be required of them. The steam frigate Powhatan, which had returned from service in the West Indies and needed considerable repairs, had just arrived and been ordered out of commission the day before the final decision of the President was communicated. Dispatch was sent revoking the decommissioning order, directing that the Powhatan be again put in commission, and to fit her without delay for brief service. The Pawnee and one or two other vessels were ordered to be in readiness for sea service on or before the 6th of April. These preparatory orders were given on Saturday, March 30.” (The Diary of Gideon Welles, Vol I, pp.15-16.)

Note: At some point between Friday, March 29 and Friday, April 5, Welles sent Commandant Foote an order to add the Powhatan to the list of ships in Lincoln’s memorandum. Presumably the impulse to do this came from Lincoln; probably, after he had gotten Seward to cooperate with him, on the basis that, instead of attempting to force an entrance into Charleston Harbor, he would make it seem as if the fleet was steaming to do that. The way to do this, the two men together probably figured out, was to tie the execution of the naval fleet’s attack on Charleston Harbor to the presence of the Powhatan.

Lincoln, leaving the details to Seward, had two naval expeditions being organized on April 1,by two different groups of people, with one officer, Lt. Porter, operating independantly of each:

One expedition going to Pensacola was under the command of Colonel Harvey Brown. Captain M.C. Meigs and Lt. Colonel E.D. Keyes were charged with the duty of requistioning the necessary men, vessels, and materials. General Scott was in overall charge, as shown by his letter to Col. Brown.

Headquarters of the Army, April 1, 1861

Col. Brown, Washington D.C.

Sir: You have been designated to take command of an expedition to reinforce and hold Fort Pickens. You will proceed to New York, where the Atlantic will be engaged, and putting on board such supplies as you can ship without delay, proceed at once to your destination. Captain Meigs will accompany you until you are established at Pickens, then he will return to Washington. Lt.-Col. Keyes will be authorized to give all necessary orders to requisition material, and steamers for transportation. The naval officers in the Gulf will be instructed to cooperate with you in every way.

Winfield Scott

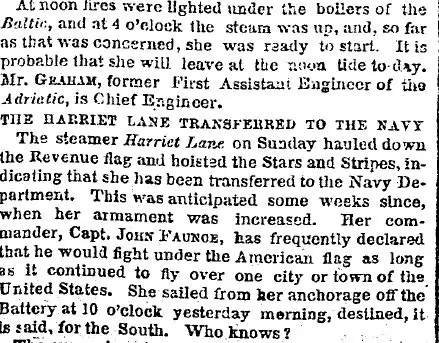

The other expedition, going to Charleston, was under the command of G.V. Fox. Fox, with Welles’s cooperation, was also ordered to New York, for the purpose of going aboard the steamer Baltic, in the company of two hundred recruits from the army station at Governor’s Island, and with supplies, then sail to Charleston for the rendevousz with the four U.S. Navy war ships, Powhatan (assigned by Welles), Pochantas, Pawnee and Harriet Lane (assigned by Lincoln). Three tugboats would also sail for the harbor as well. As Fox and Welles understood it, once all the vessels were before the harbor mouth, Fox would put the troops in whaleboats and have the tugs pull them into the harbor while the guns of the warships suppressed the fire of the Confederate batteries.

Now came Lincoln’s brilliant trick. While news of the departure of the war ships from New York would be communicated to the Confederate Government the instant the ships sailed, and though Lincoln would send a messenger to Governor Pickens of South Carolina, informing him the fleet of ships was coming, with men and materials to reinforce the garrison at Fort Sumter, he would freeze the fleet at sea by the simple device of secretly diverting the Powhatan from Charleston to Pennsacola.

Lincoln used Welles to do it..

Navy Department, (Friday) April 5, 1861

Captain Mercer, commanding U.S. Steamer Powhatan, N.Y.

The United States steamers Powhatan, Pawnee, Pocahantas and Harriet Lane will compose a naval force under your command, to be sent to the vicinity of Charleston, S.C. for the purpose of aiding in carrying out the objects of an expedition of which G.V. Fox has charge.

Should the authorities at Charleston permit the fort to be supplied, no further service will be required of the naval force under your command. Should the authorities, however, refuse to permit, or attempt to prevent the vessels having supplies on board from entering the harbor, you will protect the boats of the expedition in the object of their mission in such manner as to open the way for them, and repelling all obstructions.

You will leave New York with the Powhatan in time to be off Charleston Bar, ten miles distant from and due east of the lighthouse, on the morning of the 11th instant, there to await the arrivial of the transports with troops and stores. The Pawnee and Pocahantas will be ordered to join you there at the time mentioned, and also the Harriet Lane.

Your Obt Servt. GIDEON WELLES

Welles’s “diary” tells the balance of the story: “Sealed orders were given to Commander Rowan of the Pawnee, Commander Gillis of the Pocahantas, and captain Tanner of the Harriet Lane, to report to Captain Mercer on the 11th.” They were to “wait on station ten miles due east of the lighthouse for the Powhatan to arrive and then take their orders from Mercer.” Obviously if Mercer and the Powhatan did not appear nothing would happen, except three ships and some transports would be standing in the sea.

Lt. David Porter gives his version of events.

“Armed with [the secret orders] I bade the President good day, . . . Next morning (Wendesday April 3) I was at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, and found Captain A.H. Foote was in command. . . . He read my orders over and over. `I must telegraph to Mr. Welles before I do anything and ask for further instructions,’ he said.

`Look at these orders again,’ I said. `If you must telegraph, send a message to the President or to Mr. Seward.’ Captain Foote was puzzled. At last he said, `I will trust you. I will set to work immediately, and by night we will have the spars up on the Powhatan and the officers called back.’ Next morning I went with Foote to the office and Captain Mercer was sent for and the President’s orders read to him, and he was enjoined to secrecry. On the fourth day the Powhatan was ready for sea and Meigs informed me that he would sail on the Atlantic.’”

The New York Times

At some point, apparently while the Powhatan was still at the yard, a message from Welles arrived for Foote. It read “Prepare the Powhatan for sea with all dispatch.” According to Porter’s story, Foote turned to him and said, “There, you are dished!.”

“Not by any means,” Porter says he replied. “Let me get on board and off, and you can telegraph that the Powhatan has sailed.” Bidding Foote good by, Porter says he went on board the Powhatan and proceeded down the East River to Staten Island where Captain Mercer was put ashore. This movement took at least several hours, if not more. Just as Porter gave orders to move across the bar into the open sea, he says, a boat appeared alongside the Powhatan and a Lt. Roe came aboard and handed Porter a message.

Deliver up the Powhatan at once to Captain Mercer.

Seward

Porter gave Roe a message to telegraph back::

Have received confidential orders from the President, and shall obey them. D.D. Porter

Porter then gave orders to go ahead and the Powhatan put to sea. It was Saturday, April 6, “late afternoon.” A few days later the Powhatan was off Pensacola, in the company of the Gulf fleet watching over Colonel Brown’s transfer of troops into Fort Pickens. (D.D. Porter, Incidents and Anecdotes of the Civil War; see also, E.D. Keyes, Fifty Years of Observation of Men and Events.)

Brooklyn Navy Yard (1861)

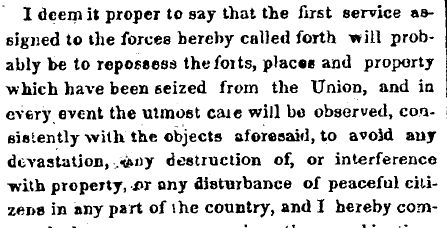

The New York Times Tells the Story

![]()

April 7, 1861

Fox’s Expeditions

April 9, 1861

April 10, 1861

![]()

On the evening of April 11, 1861, Confederate Brigadier-General P.G.T. Beaureguard, late Superintendent of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, was in command at Charleston. Word came to him from the sentry boats guarding the harbor mouth that the Harriet Lane was standing some miles off in the sea. The sighting confirmed in his mind what he already knew—a fleet of U.S. Navy war ships was bearing down on Charleston, to force an entrance into the harbor. Beaureguard had learned this, from a message brought to Governor Pickens on April 9, by an agent from Lincoln. The message said: “Expect an attempt will be made to supply Fort Sumter; if such attempt is resisted an effort will be made to throw in men, arms, and ammunition.”

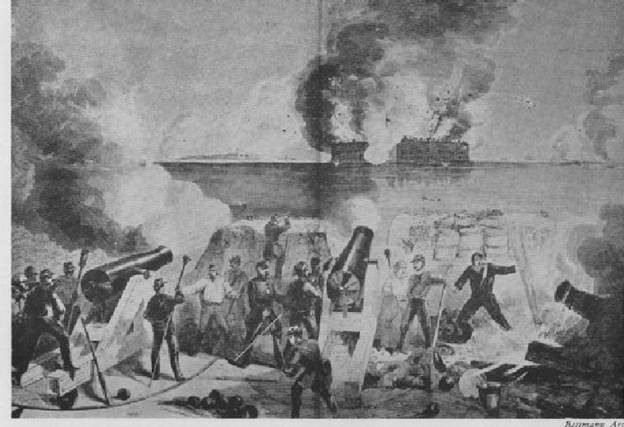

Beaureguard had informed the Confederate Government at Montgromery of this, and instructions had come from Secretary of War Walker to bombard the fort if Major Anderson did not surrender. At 4:30 a.m., on April 12, 1861, Beaureguard ordered the batteries to commence firing. |

|

Headquarters Provisional Forces

Charleston, S.C., April 12, 1861

Hon. L.P. Walker, Secretary of War

Sir: I have the honor to report our fire was opened upon Fort Sumter at 4:30 o’clock this morning. The pilots reported to me last evening that a steamer, supposed to the Harriet Lane, had appeared off the harbor. She approached slowly, and was lying off the main entrance, some ten or twelve miles, when the pilot came in.

Your Obt. Servt. G.T. Beaureguard, Brigadier General Commanding

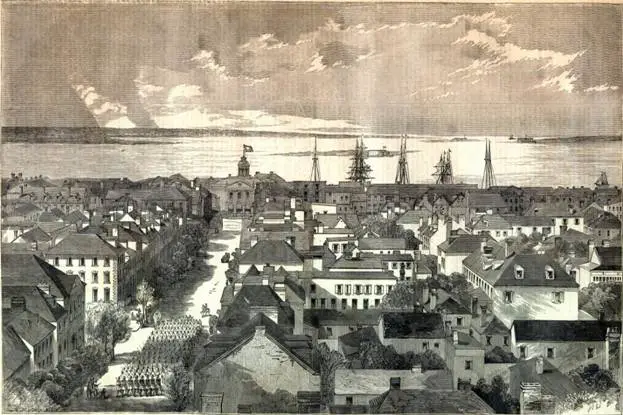

The Rebels fire on Sumter

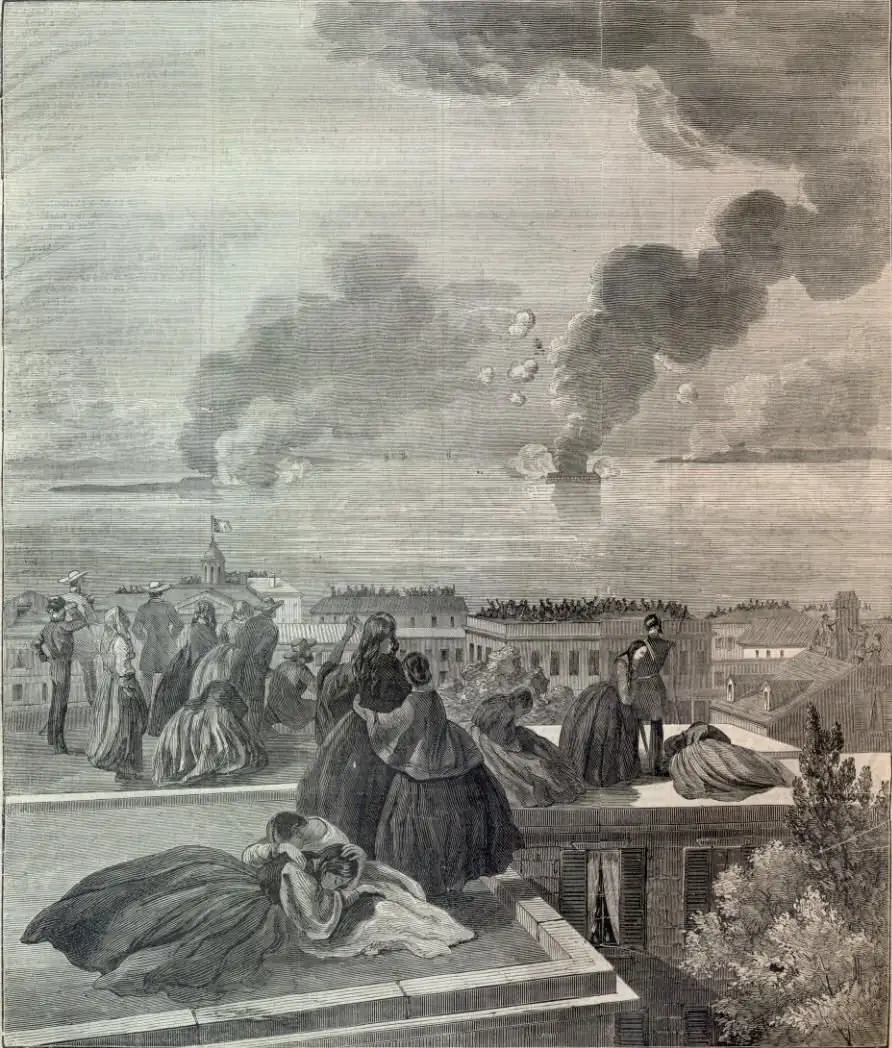

Charleston looking toward Sumter

Rebels Batteries Open on Sumter

The view From the Rooftops

|

April 12th.— I do not pretend to sleep. How can I? If Anderson does not accept terms by four, the orders are, he shall be fired upon. I count four, St. Michael’s bells chime out and I begin to hope. At half-past four the heavy booming of a cannon. I sprang out of bed, and on my knees prostrate I prayed as I never prayed before. (Mary Boykin Chesnut, A Diary From Dixie) |

The Confederate Government Blundered

That Beaureguard did not wait for the enemy to actually initiate its naval attack, ex-Confederate President Jefferson Davis wrote, in 1881:

It would have been merely, after the avowal of a hostile determination by the Government of the United States, to await an inevitable conflict with the guns of Fort Sumter and the naval forces of the United States in combination; with no possible hope of averting it, unless in the improbable event of a delay of the expected fleet for nearly four days longer. There was obviously no other course to be pursued than that announced by General Beaureguard.” (Had Davis known that the fleet had been rendered a nullity by Lincoln’s orders his decision probably would have been different.)

(See, Jefferson Davis, The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government (Appleton & Co. 1881)

Fifteen years after the end of the Civil War, Davis did not know he had been manipulated by Lincoln.

Robert Toombs, the Confederate Secretary of the Treasury, had warned Davis to wait for the actual attack. As his biographer put it, in 1913:

“Toombs entered the Cabinet meeting of April 9 after the discussion had already begun. (Lincoln’s message to Governor Pickens had been by then delivered and news of the fleet’s sailing had reached Montgomery.) Upon learning the trend of the discussion and reading the telegram from Charleston, he said: `The firing on that fort will inaugurate the war, Mr. President; it is suicide and will lose us every friend in the North. You will strike a hornet’s nest which will sting us to death. It is unnecessary; it puts us in the wrong; it is fatal.’ Davis, however, decided in favor of attack.” (Ulrich B. Phillips, The Life of Robert Toombs, MacMillan Co. 1913)

The New York Times

.’

The Historians Blind to Reality

“Lincoln had failed to peruse the orders carefully and inadvertently assigned the Powhatan simultaneously to both Pickens and Sumter.”

(Doris Kearns Goodwin, Team of Rivals: The Poltical Genius of Abraham Lincoln, Simon & Shuster 2005)

“Before Captain Mercer recognized the superiority of the President’s instructions to those of the Secretary of the Navy, the confusion was reported to Seward, who took the telegram to Welles. Then both went to the White House. Lincoln gave his support to Welles. Then the Secretary of State telegraphed these words to Porter: `Give up the Powhatan to Mercer—Seward.’ Porter held his course, being in no mood to admit that a Presidential order could be swept away by a few words telegraphed by Seward. It was a striking exhibition of Seward’s mental state at the time that he should fail to send the command in the President’s name (or, perhaps, that Lincoln let him).” (Frederic Bancroft, The Life of William H. Seward, Harpers Brothers 1899)

Note: When Porter presented Lincoln’s orders to Commandant Foote at the navy yard, Foote had received, or soon thereafter received, a telegraphed order from Welles to get the Powhatan ready for sea. Uncomfortable with holding both an order from his direct commander, Welles, and an order from Lincoln, once Porter had gone aboard the Powhatan and the ship began moving down to the bar, Foote apparently telegraphed Seward for clarification. (Why Foote chose to communicate with Seward and not Welles, only he can explain.)

At this point, Seward and Lincoln must have decided to give the Powhatan time to clear the bar, by having Seward, instead of immediately replying to Foote, take Foote’s telegram to Welles. (Seward, on his own, could not rightly have ordered one of Welles’s naval officers to do anything.)

Welles, rightly irritated that Seward had somehow gotten involved in his chain of command, expectedly charged to the White House to confront Lincoln. Welles now became a manufactured witness to show that Lincoln had “inadverently” mixed things up; in other words, to show that he had actually intended to use the war fleet to force an entrance into Charleston Harbor, rather than that he had intentionally orchrestrated events to make it seem that was his intent.

The proof of this lies in what Welles says was Lincoln’s response to his complaint of Seward’s interference with Navy affairs. Lincoln, Welles says, now told Seward to reply to Foote with “Welles is right, tell Porter to give the Powhatan to Mercer.” Having given Porter direct orders, Lincoln would not have expected Porter to obey Seward’s. Had the “give back” order come to Porter from Welles, he might have obeyed it.

Striking indeed that the myth of Lincoln’s innocent mixup could be sustained by the historians so long. But then Lincoln is a holy icon to the historians: they are loath to show him in his full nature: even when his own words expose himself.

On July 4, 1861, in a special message to the Congress, he gave this explanation of what had happened in the runup to the bombardment of Sumter.

“It was believed that to abandon Sumter would be utterly ruineous; that the necessity under which it was done would not be fully understood; that by many it would be construed as a part of a voluntary policy; that at home it would discourage the friends of the Union, embolden its adversaries, and go far to insure to the latter a recognition abroad; that, in fact, it would be our national destruction consummated. This could not be allowed. (italics original)

In precaution, the Government had commenced preparing an expedition, as well adapted as might be, to relieve Fort Sumter, which expedition was intended to be ultimately used or not, according to circumstances. It was resolved to sent it forward. It was further resolved to notify the governor of South Carolina that he might expect an attempt would be made to provision the fort; and that, if the attempt should not be resisted, there would be no effort to throw in troops. This notice was given; whereupon the fort was attacked and bombarded to its fall. Without even awaiting the arrival of the provisioning expedition. (Italics added.)

It is thus seen that the assault upon Sumter was in no sense a matter of self defense on the part of the assailants They well knew that the garrison in the fort could not possible commit agression upon them. They knew that the giving of bread to the few brave men of the garrison was all that on that occasion would be attempted, unless themselves, by resisting so much, should provoke more. (Wow, Lincoln!) They knew the Government desired to keep the garrison in the fort as visible evidence that the Union was preserved—trusting to time, discussion, and the ballot-box for final adjustment.” (Italics added.) (See, Congressional Globe, Appendix, Debates and Proceedings, First Session of the Thirty-Seventh Congress, 1861)

Your resistence provokes me. Is that what he said? Never did an accomplished trial lawyer ever spill more ink in the eyes of his audience, pour more sonorous sound in its ears than Lincoln did here. (Shhhhh, not a word said about the Powhatan’s “mixup.”)

The Republican Senators Give Lincoln’s Conduct Their Spin

During the several weeks debate that went on in Congress after it came into special session, over the issue of approving by joint resolution Lincoln’s conduct in initating the war, Senator John Breckinridge of Kentucky engaged in argument with the leading figures of the majority party now in power.

Of the proposed resolution, Senator Breckinridge said, “It proposes that all of the extraordinary acts of the President be, and hereby are, approved and declared legal and valid as if they had been done under the authority of the Congress. The resolution seems, on the fact of it, to admit the acts of the President were not performed in obedience to the Constitution and the laws. I should like to hear some reasons showing the power of Congress to cure a breach of the Constitution or to indemnify the President against violations of the laws. Congress has no more right to make valid a violation of the Constitution or the laws than does the President to `proclaim.’ If a bare majority of the two houses of Congress by joint resolution, make that constitutional which was unconstitutional, by the same reasoning it may confer upon the President in the future powers not granted by the Constitution. This resolution contains the very essence of a Government without limitations of powers.”

I deny that the President may violate the Constitution upon the excuse of necessity. The doctrine is utterly subversive of the Constitution; and it substitutes, especially where you make him the ultimate judge of that necessity, and his decision not to be appealed from, the will of one man for a written constitution.”

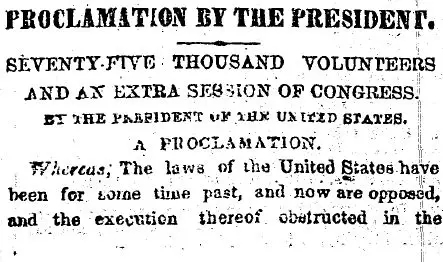

In reply to Breckinridge, several senators focused their remarks on the source of the “necessity” that justified the President’s proclamation of April 15 calling for 75,000 volunteers to suppress “insurrection.”

Mr. John Sherman, freshman senator from Ohio. speaks:

“Senator Breckinridge says that the President has brought on this war—that by issuing the proclamation of April 15 he commenced the war. I ask the honorable senator from Kentucky who fired upon our flag at Charleston? Was not that an act of war? Who attacked our fort at Sumter? Who fired on one of Kentucky’s distinquished citizens, and even fired upon him after he had raised a flag of truce, fired upon him while the buildings were burning over his head? Was this no act of war?”

Mr. Browning of Illinois, speaks:

“I ask the senator from Kentucky, what, in his judgment, should the President have done when the flag was fired upon, when Fort Sumter was attacked, when a starving handful of loyal men in the discharge of their lawful duties were fired upon? Should the government have humbled itself in the face of treason? Was that what he thinks should have been done? The alternative was either disgraceful submission, or manly, constitutional, heroic resistence to the infamies that had been committed against us. This is strictly a war of self defense as ever a people were compelled to prosecute. It is strictly a war of self defense and nothing else.”

Senator Johnson, of Tennessee, speaks:

“On the 11th of April Beauregard had an interview with Anderson and made a proposition for him to surrender. Major Anderson refused; but he said at the same time that by the 15th his provisions would give out. We find that after being in possession of this fact, on the morning of the 12th Beauregard commenced the bombardment, fired upon your fort and upon your men. They knew that in three days Anderson would be compelled to surrender; but they wanted war. It was indispensible to produce an excitement in order to hurry Virginia out of the Union, and they commenced the war. Who commenced the war? Who struck the first blow? Was it not South Carolina in seceding? And yet you talk about the President having brought on the war by his own motion, when these facts are incontrovertible.”

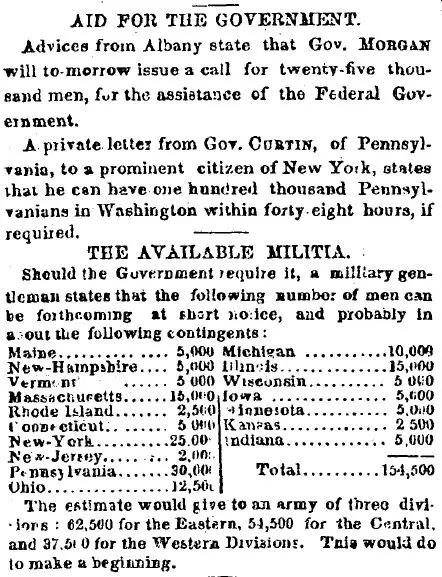

President Lincoln Rushes to the Public with his Proclamations

The New York Times

and in Charleston

The Status of Virginia?

April 12

April 15

April 20

The Governors Respond to Lincoln’s Call

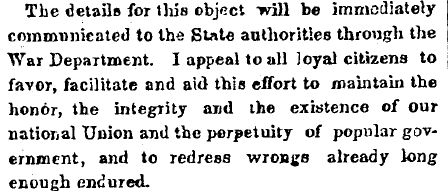

On April 15, Lincoln called forth the militia of the several states of the Union, to the aggregate of 75,000 men, the details of the call to be communicated to the governors through the War Department.

On the same day, Simon Cameron, Secretary of War, telegraphed the governors:

“Under the act of Congress `for calling forth the militia to execute the laws of the Union’ approved February 28, 1795. I request the immediate detachment from the militia of each of your states the quota designated below, to serve as riflemen for the period of three months. . . “ Forty Regular army officers were dispatched to the states to muster into the service of the United States the militia collected in camps and organized into companies and companies into regiments. The Northern StatesThe same day these communications were sent from Washington, Governor Washburn of Maine telegraphed Cameron: “The people of Maine will rally to the maintenance of the government and the Union.” Massachusetts Governor John A. Andrew wired, “By what rout shall we send?” Governor William Dennison of Ohio telegraphed Lincoln—“We will furnish the largest number you will receive.” Governor Goodwin of New Hampshire wrote Cameron: “Immediate measures will be adopted for the formation of companies.” Samuel Kirkwood of Iowa wrote on April 16 to Cameron: “nine-tenths of the people here are with you.” Governor Morton of Indiana wired, “the six regiments will be full in three days.” Governor Yates of Illinois chimed in with “Send requisitions for arms and accouterments.” Alex Randall of Wisconsin wired: “The call for one regiment of militia will be promptly met.” Same from Governor Erasmus Fairbanks of Vermont. The governors of New York and New Jersey asked for clarification. The Special Case of PennsylvaniaOn April 17, Governor Andrew Curtin of Pennsylvania wrote Cameron a message that led to a consequence no one apparently made an effort to avoid: “Volunteers are arriving. Shall I order the Philadelphia regiments to march?” Cameron answered, “The President has modified the requisition made upon you for troops from Pennsylvania so as to make it 14 instead of 16 regiments. You are entitled to 2 major generals and 3 brigadier generals.”

Governor Curtin promptly appointed Robert Patterson, aged 74, an old crony of General Scott, now a wealthy Pennsylvania businessman, as Major General of Pennsylvania’s Militia. President Lincoln appointed Patterson to command for the period of three months enlistment the Department of Pennsylvania. On April 26 Patterson wired Curtin that his force should be increased by an additional twenty-five regiments. Curtin wired Cameron to say that he was moving to recruit these additional regiments, that many companies were already on the march and asked that an immediate order be sent to Patterson instructing him to receive the additional regiments. The Border StatesGovernor John Ellis of North Carolina, responded in the vein Virginia’s Governor John Letcher did: “I can be no party to this wicked violation of the laws of the country.” Governor Magoffin of Kentucky, likewise, was not pleased. He wrote, “Kentucky will furnish no troops for the wicked purpose of subduing her sister Southern states.” Governor Thomas Hicks of Maryland, walking the tightrope between martial law and secession, called personally on Lincoln to say Maryland would provide two regiments to remain inside Maryland. Isham G. Harris, Governor of Tennessee wired Cameron, “Tennessee will not furnish a single man for purpose of coercion.” Governor C.F. Jackson of Missouri wired the same, “Not one man will the State of Missouri furnish to carry on such an unholy crusade.” |

II

President Lincoln Suspends The Writ of Habeas Corpus

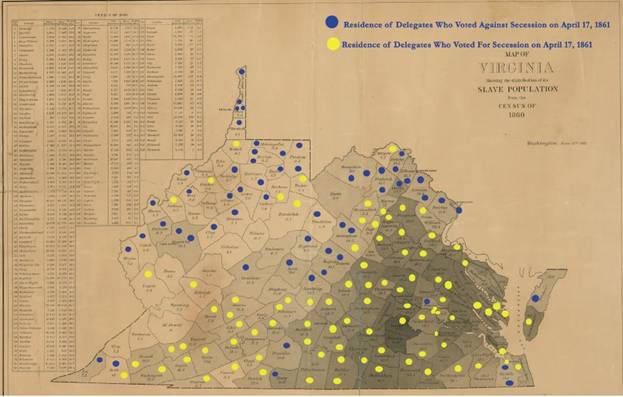

On April 15, 1861, President Lincoln called for troops. On April 17, Virginia seceded. On April 19, a large mob of Baltimore residents attacked the soldiers of a Massachusetts regiment passing through the city to Washington. Several soldiers and civilians were killed. On April 27, Abraham Lincoln ordered General Scott to arrest any civilians Scott, or his subordinate officers, thought might pose a threat to the Union.

President Lincoln’s Order to General Scott

April 27, 1861

To the Commanding General of the Army of the United States:

You are engaged in suppressing an insurrection against the laws of the United States. If at any point in the vicinity of the military railroad line between Philadelphia and Washington, you find resistance which renders it necessary to suspend the writ of Habeas Corpus for the public safety, you, personally or through an officer in command at the point the resistance occurs, are authorized to suspend the writ.

Abraham Lincoln

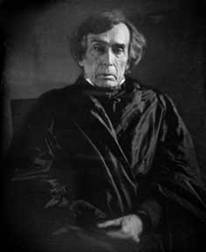

The Merriman Case

John Merryman, a Maryland Militia member was seized by the military

and imprisoned at Fort McHenry in Baltimore Harbor. Merryman, through counsel,

filed a petition for the issuance of a writ of habeas corpus with the United

States Circuit Court for the District of Maryland. Chief Justice Roger Taney,

sitting as presiding judge over the district, granted the petition, and the

writ was issued and served on Merriman’s custodian, General George Cadwalader.

When Cadwalader refused to produce Merriman in court, Chief Justice Taney—in

his capacity as presiding circuit judge—issued an opinion holding that only

Congress had the authority to suspend the writ

John Merryman, a Maryland Militia member was seized by the military

and imprisoned at Fort McHenry in Baltimore Harbor. Merryman, through counsel,

filed a petition for the issuance of a writ of habeas corpus with the United

States Circuit Court for the District of Maryland. Chief Justice Roger Taney,

sitting as presiding judge over the district, granted the petition, and the

writ was issued and served on Merriman’s custodian, General George Cadwalader.

When Cadwalader refused to produce Merriman in court, Chief Justice Taney—in

his capacity as presiding circuit judge—issued an opinion holding that only

Congress had the authority to suspend the writ

The basis of the Court’s jurisdiction was the 14th section of the Judiciary Act of 1789 which gave the courts of the United States, as well as each justice of the Supreme Court, power to grant habeas corpus petitions and issue writs for the purpose of making a factual inquiry into the grounds the Government asserted as justification for holding the petitioner.

Merryman’s petition set forth the allegations that, on May 25, 1861, he had been residing peaceably at his home in Baltimore County when soldiers entered, seized him and imprisoned him in Fort McHenry.General Cadwalder replied in writing to Merryman’s petition, offering as lawful authority the fact that Merryman had been seized by a General Keim, of Pennsylvania, and brought to Cadwalder at Fort McHenry. Keim, Cadwalder asserted, believed that Merryman was a traitor and a rebel who had burned railroad bridges in Pennsylvania. Cadwalder, offering no facts to support this hearsay belief, refused to obey the writ on the ground that “he was duly authorized by the president to suspend it.”

Taney summed up the situation this way: “I understand that the president not only claims the right to suspend the writ of habeas corpus himself, at his discretion, but to delegate that discretionary power to a military officer, and to leave it to him to determine whether he will or will not obey judicial process that may be served upon him.”

Taney then stated his basis for rejecting the President’s claim of power to suspend the writ: “This is one of those points of constitutional law upon which there is no difference of opinion, as I think it is admitted by everyone, that the privilege of the writ cannot be suspended, except by act of Congress. Having, therefore, regarded the question as too plain and well settled to be open to dispute, . . .I should have contented myself with referring to the clause in the constitution (Art I, Section 9.), and to the construction it received from every jurist since the founding.

But, given the response received, I state plainly and fully the grounds of my opinion.”Section 9 of Article I has not the slightest reference to the Executive department. . . The great importance which the framers of the constitution attached to the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus, to protect the liberty of the citizen, is proved by the fact, that its suspension, except in cases of invasion or rebellion, is first in the list of prohibited powers; and even in these cases the power is denied, and its exercise prohibited, unless the public safety require it.” (The constitution of the Confederate States had the same provision; see Article I, Section 7, subparagraph 3.)

It is Congress, Taney wrote, that the framers made “the judge of whether the public safety does or does not require” suspension of the writ in the context only of invasion or rebellion. “There is not a word in the Constitution,” he went on, “that can furnish the slightest ground to justify the exercise of this power” by the president.

President Lincoln, by implication, was basing his exercise of the power on the Executive’s oath of office and his status as Commander-in-Chief as described in Article II. In other words, Lincoln was claiming, by reference to these two elements in Article II, that the framers meant to give the Executive the inherent power to suspend the writ of habeas corpus whenever he felt it necessary to do so.

|

Chief Justice Taney rejected this contention out of hand: “The only power which the president possesses, where the `life, liberty or property’ of a private citizen is concerned, is the power and duty prescribed in the third section of the second article, which requires `that he shall take care that the laws be faithfully executed.’ He is not authorized to execute the laws himself, or through agents or officers, civil or military, appointed by himself, but he is to take care that they be faithfully carried into execution, as they are expounded and adjudged by the coordinate branch of the government to which that duty is assigned by the constitution. (Thus) in exercising this power he acts in subordination to judicial authority, assisting it to execute its process and enforce its judgments.” (Justice Taney’s reasoning here is based on Chief Justice John Marshall’s famous pronouncement in Marbury v. Madison (1807) that the Supreme Court, and only the Supreme Court, is assigned the task, under the Constitution, of interpreting its words.) |

What about the constant claim of Lincoln’s successors, “But I think it’s necessary.”

Mr. Chief Justice Taney answered this:

“With such provisions in the constitution, expressed in language too clear to be misunderstood by any one, I can see no ground whatever for supposing that the president, in any emergency, or in any state of things, can authorize the suspension of the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus, or the arrest of a citizen, except in aid of the judicial power. He certainly does not faithfully execute the law, if he takes upon himself legislative power, by suspending the writ of habeas corpus, and the judicial power also, by arresting and imprisoning a person without due process of law;” i.e., ignoring the person’s constitutional rights, to counsel, to a statement of the charges against him, and in a trial by jury to proof beyond a reasonable doubt of his guilt of the charges. Lincoln, here, in other words, had made the Federal Government a one man show.

But what about the idea of the existence of a “fundamental law” that Lincoln, in his inaugural address, said recognizes that the Federal Government, regardless of the constitution, has the inherent right to preserve itself?

Here, Chief Justice Taney, writing for himself alone, and not speaking for the Supreme Court itself, expressed the reasoning of his rejection of the idea:

“No such argument can be drawn from the nature of sovereignty, or the necessity of government, for self defense in times of tumult and danger. The government of the United States is one of delegated and limited powers; it derives its existence and authority altogether from the constitution, and neither of its branches, executive, legislative, or judicial, can exercise any of the powers of government beyond those specified and granted; for the tenth article of the amendments to the constitution, in express terms, provides that `the powers not delegated to the United States by the constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, are reserved to the states, respectively, or to the people.’”

Lincoln’s position was that the president might do anything, regardless of so-called prohibitions in the constitution, which he believes is necessary to protect the Federal Government from losing control of the land and people it governs. Lincoln put his position this way, in his message to Congress delivered July 4, 1861:

“Soon after the first call for militia, it was considered a duty to authorize the commanding general in proper cases, according to his discretion, to suspend the writ of habeas corpus, or, in other words, to arrest and detain, without resort to the ordinary processes and forms of law, such individuals as he might deem dangerous to the public safety. . . The legality and propriety of what has been done under it are questioned.”

What is Lincoln’s basis for justifying his usurpation of the power to suspend the writ?

“Of course some consideration was given to the questions of power and propriety before this matter was acted upon. The whole of the laws which were required to be faithfully executed by me were being resisted and failing of execution in nearly a third of the states. (But not in Maryland, or in Baltimore County). . .”

Here comes the President’s reasoning for the usurpation!

“Must the whole of the laws be allowed to fail of execution (in the rebel states), even (if) it’s perfectly clear that by the use of the means necessary to their execution (in the rebel states) some single (silly) law. . (applied in a loyal state).should to a very limited extent be violated?”

Abraham Lincoln spent thirty years practicing as a trial lawyer in all the courts of Illinois, reportedly winning the jury’s verdict more often than not. He was publicly acclaimed, since his string of debates with Stephen Douglas for a senate seat, in 1856, as a great speaker and writer of speeches which were clear and lucid in reasoning and which built elaborate arguments in support of the policies of the Republican Party. And yet this written language, preserved in the Congressional Globe, with its confusing syntax, is the best argument he can come up?

What an argument has he constructed out of thin air. He is saying, when the ambiguity is cut through, simply this: “It was absolutely necessary to suspend the writ of habeas corpus in the loyal state of Maryland in order to ensure that the whole of the laws of the United States would be executed in the Confederate States of America.” This must have sounded like nonsense to the public mind.

Knowing this, Lincoln, in his message, tried to bolster his argument with more words, but ended up just saying the same thing over again.

“To state the question more directly: are all the laws but one to go unexecuted, and the government itself go to pieces, lest this one be violated?”

The Government was in danger of going to pieces if the President did not have the inherent power to seize and imprison citizens in Maryland, without judicial process? Hardly. All the laws but one were not going unexecuted in the State of Maryland or in Baltimore County where John Merryman resided. Nor was the government in any real danger of “going to pieces” merely because the Constitution expressly and plainly authorized only the Congress to suspend that “one law” that was so dangerous to execute in times where other States had abandoned the Union. And, of course, by not calling Congress into session immediately upon taking the oath of office, Lincoln had made the conscious decision to keep Congress out of the decision-making process of what to do with the Confederate States of America. Lincoln wanted no debate.

To Lincoln the great writ of habeas corpus that has come down to us through eight hundred years of English Common Law history, is a law “made in such extreme tenderness of the citizen’s liberty that practically it relieves more of the guilty than of the innocent.” And therefore, the clear words of the Constitution can be ignored by the President whenever he or she claims to be acting to preserve the government from hostile forces arraigned against it

Yet again, Lincoln tried to come at his action a different way, a way

every war time president who has followed him has seized upon as justification

for tyranny. “In such a case,” Lincoln wrote, “would not the official oath be

broken if the Government should be overthrown, when it was believed that

disregarding the single law would tend to preserve it?” According to Lincoln, then, the President’s fear that the government might be overthrown,

however unreasonable that fear might be under the plain circumstances of the

case, justifies ignoring judicial process and the law. In 1942, President

Franklin D. Roosevelt, issuing an order for the military imprisonment of

hundreds of thousands of American citizens, used this argument.. (See the

cases cited in the trial lawyer’s notebook.)

Yet again, Lincoln tried to come at his action a different way, a way

every war time president who has followed him has seized upon as justification

for tyranny. “In such a case,” Lincoln wrote, “would not the official oath be

broken if the Government should be overthrown, when it was believed that

disregarding the single law would tend to preserve it?” According to Lincoln, then, the President’s fear that the government might be overthrown,

however unreasonable that fear might be under the plain circumstances of the

case, justifies ignoring judicial process and the law. In 1942, President

Franklin D. Roosevelt, issuing an order for the military imprisonment of

hundreds of thousands of American citizens, used this argument.. (See the

cases cited in the trial lawyer’s notebook.)

So it is seen how all presidents can be expected to

think: whoever they are, whatever party they belong to, whatever their

education and experience in life may be, they will  always seize upon the oath of office to claim for themselves

the power to do whatever they think is necessary to preserve the government,

and to the winds they will throw silly laws written into the constitution that

are too tender for their taste given the times. But, still we are

lucky, aren’t we, that it was Lincoln who set the standard? That

is why we the people have erected a massive block of marble at the foot of Constitution Avenue to honor the spirit of him.

always seize upon the oath of office to claim for themselves

the power to do whatever they think is necessary to preserve the government,

and to the winds they will throw silly laws written into the constitution that

are too tender for their taste given the times. But, still we are

lucky, aren’t we, that it was Lincoln who set the standard? That

is why we the people have erected a massive block of marble at the foot of Constitution Avenue to honor the spirit of him.

Lincoln Supports His Position With Attorney General Bate’s Opinion

The day following the day his message was read into the congressional record, Lincoln delivered to the Congress a written opinion ostensibly authored by his attorney general, Edward Bates. Though the opinion contains more words of argument they all boil down to the same old argument of necessity.

“It is the plain duty of the President. . . [to put] down rebellion. The duty to suppress the insurrection being obvious and imperative, the two acts of Congress, of 1795 and 1807, come to his aid, and furnish the physical force that he needs.” (This much is true.)

“The manner in which he puts down the insurrection is not prescribed by any law. . .(This is not true: the President must act in the context of due process of law.) He is, therefore, necessarily thrown upon his discretion, as to the manner in which he will use his means to meet the various exigencies as they arise. If the rebels employ spies to forward rebellion, he may arrest them and imprison them, rending them powerless for mischief, until the exigency has passed.”

“In such a state of things, the President must, of necessity, be the sole judge, both of the exigency which requires him to act, and of the manner he acts. . .”

“Since the President has the legal discretionary power to arrest and imprison persons suspected of traitorous complicity, it might seem unnecessary to prove that, in such case, the President is justified in refusing to obey a writ of habeas corpus issued by a court or judge, commanding him to produce the body of his prisoner, and then yield himself to the judgment of the court.”

“If it be true, as I have assumed, that the President and the Judiciary are co-ordinate departments of government, and the one not subordinate to the other, I do not understand how it can be legally possible for a judge to issue a command to the President to come before him and submit to his judgment and, in case of disobedience, treat him as a criminal, in contempt of a higher authority, and punish him.”

“Besides the whole subject matter is political and not judicial. The insurrection itself is purely political. Its object is to destroy the political government and to establish another government upon its ruins. As the political chief of the nation, the Constitution charges the President with its preservation, protection and defense. And in that character, he wages open war against armed rebellion, and arrests and holds in custody those, whom, in the exercise of his political discretion, he believes to be friends of rebellion, which it is his special duty to suppress.”

“The judiciary department has no political powers and no court of judge can take cognizance of the political acts of the President, or undertake to revise or reverse his political decisions.”

All these words that Attorney General Edward Bates (standing in for Lincoln) provides, mean merely that upon the mere allegation of conduct the President deems dangerous to the preservation of the government, an American citizen residing in a loyal state may be arrested by the military and throw into prison without judicial process.

Chief Justice Taney’s fair warning to we Americans

In closing his opinion, in Merryman, Mr. Chief Justice Taney spoke to us of our time when he wrote, “These great fundamental laws (expressed in the 4th, 5th, and 6th amendments to the constitution), which congress itself could not suspend, have been disregarded and suspended, like the writ of habeas corpus, by a military order, supported by force of arms. I can only say that if the authority which the constitution has confided to the judicial department, may thus, upon any pretext, be usurped by the military power, at its discretion, the people of the United States are no longer living under a government of laws, but every citizen holds his life, liberty, and property at the will and pleasure of the army officer in whose military district he may happen to be found.” For over thirteen thousand civilians, this was their fate during the civil war. For hundreds of thousands, it was their fate in World War II. What, one wonders, may happen someday to the Muslim-Americans in Dearborn.

President Lincoln Expands His Suspension of the Writ

On September 24, 1862, seven days after the Battle of the Antietam, and just as the Confederate army, under General Braxton Bragg, reached the outskirts of Louisville, President Lincoln issued his second proclamation regarding the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus.

“Whereas, it has become necessary to call into service portions of the militia of the States by draft in order to suppress the insurrection existing in the United States, and disloyal persons are not restrained by the ordinary processes of law from hindering this measure. . . Now, therefore, be it ordered that all aiders and abettors of the Rebels within the United States, and all persons discouraging volunteer enlistments, resisting military drafts, or guilty of any disloyal practice, shall be subject to martial law and subject to trial and punishment by military commission.” ( A “disloyal practice” was anything President Lincoln said it was.)

In anticipation of the President’s proclamation, the Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton, had already issued instructions to the Army that all persons would be seized and imprisoned who “tried to evade the draft” or who were suspected of committing “disloyal practices,” such as making public speeches criticizing the Government.

The Fort Wayne Sentinel, a Democrat newspaper, editorialized about this on September 27, 1862: “The Constitution has been set aside, freedom of speech and the press destroyed, our citizens subjected to arbitrary arrests, and the right of habeas corpus suspended. If the overthrow of the Constitution. . . is to be excused on the plea of military necessity, it must be obvious that the sooner the war is brought to an end the better.”

What plainer words do we need to understand? War happens. The world, today, is, no question about it, on the move toward a world order—the big dogs have thrown their weight around for two hundred years, been put in their places by two world wars, and now see the point of peace and cooperation; but there are still the small dogs, Venezuela and Iran, for example, puffing up and vying for a recognized slot; and there is China where the Communist Party rules. But there is one people, one race inhabiting the earth: America is the hard-working model, of how to assimulate into one society all the strands of the race, with their diverse colors, prejudices, and religions. The working principle that stirs the polticial stew is freedom. Who, in their right mind, would want to come to America, if not for the freedom? So we can expect the world order to materialize in the form of freedom, if the model of America fails? Not likely.

The Congress Finally Passes An Act Suspending the Writ

Six months later, on March 3, 1863, as thousands of citizens were being seized by the military, thrown in military prisons and tired by military commissions, the Congress finally stepped in and passed the 1863 Habeas Corpus Act which authorized the President to suspend the writ “in any case throughout the United States whenever, in his judgment, the public safety required it.” Quickly the President established “Military Districts” throughout the Free States bordering the Confederacy.

The Congress, in doing this, however, did not immunize the President from the reach of judicial process; it had the political fortitude, backbone, at least to specify in the Act that persons held by the military, who were within the class of nonbelligerents—those persons who were not captured soldiers of the enemy’s armies—were to have the right to petition the courts for issuance of the writ, and if they had not been indicted by a grand jury for crimes allegedly committed, they were to be released from their imprisonment.

Ignoring this, the Judge Advocate of the Army interpreted the congressional Act as inapplicable to persons “triable by court martial and military commission,” such as “prisoners arrested as guerillas or bushwhackers or as being connected with or aiding these.” And, in 1864, Congress authorized military commanders to execute the sentences of military commissions against persons who had violated “the laws and customs of war,” such as suspected spies, mutineers, deserters, saboteurs, and marauders.

. The Milligan Case

Lambdin P. Milligan was admitted to the Indiana bar in 1835. He

established a litigation practice in Huntington, Indiana, in the northeastern

corner of the state, where he became well known as a Democrat who was active in

party politics. In the years before the war, he made public speeches about New England’s exploitation of Indiana farmers, and, during the war, he made speeches about

Republican responsibility for causing it. For example, the Columbia City Republican

newspaper reported, on July 28, 1862: “Of all the infamous harangues ever

delivered in any loyal state of the Union, none can compare to it in traitorous

malignity than the one hissed forth from the villainous lips of Lambdin P.

Milligan on Saturday last.”

Lambdin P. Milligan was admitted to the Indiana bar in 1835. He

established a litigation practice in Huntington, Indiana, in the northeastern

corner of the state, where he became well known as a Democrat who was active in

party politics. In the years before the war, he made public speeches about New England’s exploitation of Indiana farmers, and, during the war, he made speeches about

Republican responsibility for causing it. For example, the Columbia City Republican

newspaper reported, on July 28, 1862: “Of all the infamous harangues ever

delivered in any loyal state of the Union, none can compare to it in traitorous

malignity than the one hissed forth from the villainous lips of Lambdin P.

Milligan on Saturday last.”

In the fall of 1863, it became known that Milligan had joined a Democrat organization known as the Knights of the Golden Circle. At the same time there existed in Indiana Republican clubs, such as the Union Club and the Loyalty League, the members of which spied on their neighbors, on the look out for “disloyal practices.” Acting on a tip from these sources the military raided a print shop owned by a member of the Democratic Party and found, along with rifles and ammunition, letters linking the Democrats to the Knights of the Golden Circle. One of these letters was signed by Lambdin Milligan.

In October 1864, military officers, with Milligan’s letter as the excuse, arrested Milligan at his home. Milligan, having just had leg surgery, was unable to walk. The officers carried him out of the house and, by train, took him to Indianapolis and threw him in a military prison. Less than three weeks later, Milligan was on trial before a military commission, charged with “conspiracy” against the United States, aiding the rebels, inciting insurrection, committing “disloyal practices” and violating the “laws of war.”

The commission was established by the commanding general of the Indiana military district and was composed of five army officers, presided over by a “Judge Advocate” whose function was to rule on all matters involving procedure and the admission of evidence. The substance of the case the Government put on trial was that Milligan and his co-defendants were guilty by association of the charges made against them. They were members of the Democratic Party in Indiana which in turn was a stand-in for the allegedly treasonous organization known as the Knights of the Golden Circle. “When a person takes upon himself the responsibility of joining an unlawful body, he takes upon himself responsibility for every unlawful act of that body,” the Judge Advocate intoned; membership alone, in other words, made Milligan guilty.

On December 6, 1864, the military commission found Milligan guilty of the offenses charged and sentenced him “to be hanged by the neck until dead.” Six months later, after President Lincoln had been shot and killed, his successor, Andrew Johnson, authorized the military authorities to execute the sentence of death.

At this point, David Davis, the judge who rode with Lincoln on the Illinois circuit for years, and who Lincoln had appointed to the Supreme Court bench,

traveled to Indiana and met with its wartime Republican governor, Orton Morton.

Davis influenced Morton to write to John Pettit, the speaker of the Indiana house of representatives, entreating him to go to President Johnson to seek reprieve

for Milligan. Pettit agreed, telling Morton that he doubted the military

commission had legal authority to act as it did, given the fact the courts were

open at all times in Indiana, and that he thought “at the beginning of peace

the President ought not to pick Indiana to have a military execution in.”

At this point, David Davis, the judge who rode with Lincoln on the Illinois circuit for years, and who Lincoln had appointed to the Supreme Court bench,

traveled to Indiana and met with its wartime Republican governor, Orton Morton.

Davis influenced Morton to write to John Pettit, the speaker of the Indiana house of representatives, entreating him to go to President Johnson to seek reprieve

for Milligan. Pettit agreed, telling Morton that he doubted the military

commission had legal authority to act as it did, given the fact the courts were

open at all times in Indiana, and that he thought “at the beginning of peace

the President ought not to pick Indiana to have a military execution in.”

Milligan himself wrote to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton.

|

On May 10, 1865, Milligan, through counsel, petitioned the federal circuit court at Indianapolis for a writ of habeas corpus. The two judge panel consisted of District Court Judge David McDonald, and Supreme Court Justice David Davis. The two judge panel then certified certain questions to the United States Supreme Court. While the petition was pending, President Johnson commuted Milligan’s sentence to life imprisonment.

Lincoln was dead, the armies were evaporating, the time had finally come for the Supreme Court to right wrong.

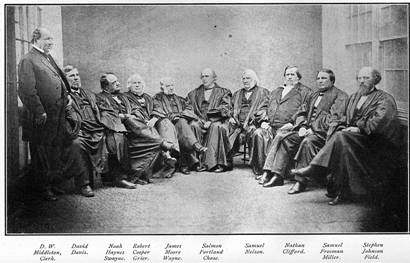

Supreme Court Justice David Davis Writes a Majority Opinion

Chief Justice Salmon Chase and Three Associates Did Not Completely

Agree With

All the justices agreed with Davis that President Lincoln did not have the inherent power to cause a civilian residing in a state free of military fighting and where the courts were open, to be arrested, thrown in a military prison, and sentenced to death by a military commission. Though Lincoln had issued illegal proclamations suspending the writ of habeas corpus, it was true the Congress eventually ratified his conduct by passing the 1863 Habeas Corpus Act, but, in doing so, it did not provide the President with authority to impose death sentences, or any sentence, on civilians by military commission. The result of the President’s conduct, therefore, was tyranny.

What source did the military commission that tried Milligan derive its authority?

Mr. Justice Davis set down the rule: “Certainly no part of the judicial power of the United States was conferred on them;” as it is not pretended that military commissions are courts ordained and established by Congress. These commissions cannot be justified on the ground that the President mandates them, because he is supposed to be controlled by law, and has his appropriate sphere of duty, which is to execute, not make laws.”

“It was the manifest design of Congress to secure a certain remedy by which any one, deprived of liberty, could obtain it, if there was a judicial failure to find cause of offense against him.”

All of this, Chief Justice Chase, and his adherents, concurred with, but with this pronouncement of Justice Davis he did not.

“No doctrine, involving more pernicious consequences, was ever invented by the wit of man than that any of the Constitution’s provisions (the rights guaranteed by the 4th, 5th, and 6th amendments, for example) can be suspended during any of the great exigencies of government. Such a doctrine leads directly to anarchy or despotism. The theory of necessity on which it is based is false; for the government, within the Constitution, has all the powers granted to it, which are necessary to preserve its existence.”

In saying this, Justice Davis, with a majority of the court with him, went beyond the factual situation of Milligan’s case and declared that, regardless of the plea of military necessity, Congress, much less the President, could not suspend the Bill of Rights by authorizing the seizure, imprisonment, and trial by military commission of American citizens in the United States.

Chief Justice Chase and his minority agreed completely with the majority that Milligan was entitled to petition the court for habeas corpus, that, under the congressional act of 1863, he was entitled to be discharged, and that the military commission that tried him had no jurisdiction to try and sentence him. But the minority’s agreement with the majority stopped there. The majority had gone beyond the 1863 Habeas Corpus Act, as the basis of decision, when it asserted as to the concept of a military commission that “Congress had no power to authorize it.”

The majority’s declaration that no exigency of government could justify the suspension of the Bill of Rights, under the constitution, was, Chase wrote, an “expression of opinion” that seemed “calculated to cripple the constitutional powers of the government, and to augment the public dangers in times of invasion and rebellion.”

The Sixth Amendment to the Constitution states plainly: “In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right of a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and District wherein the crime shall have been committed. . . , and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the assistance of counsel for his defense.”

The Fifth Amendment to the Constitution states plainly: “[N]o person shall be held to answer for a capital or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a grand jury.”

Despite the clear language of these constitutional amendments, the Milligan minority took the view that, “We think that Congress has power, though not exercised, to authorize the military commission which was held in Indiana.”

And here are their reasons:

“The Constitution itself provides for military government as well as for civil government. What is the proper sphere of military government? It is not denied that Congress has power to make rules for the government of the army and navy which includes the power to provide for trial and punishment by military courts without a jury. . . “

“We think, therefore, that the power of Congress, in the government of the land and naval forces is not at all affected by [the Bill of Rights]. It is not necessary to attempt any precise definition of the boundaries of this power. But may it not be said that government includes protection and defense as well as the regulation of internal administration? And is it impossible to imagine cases in which citizens conspiring or attempting the destruction or great injury of the national forces may be subjected by Congress to military trial and punishment in the just exercise of this undoubted constitutional power?”

So, then, Chase’s logic goes, because the Congress plainly has power to govern the armed forces without regard to the Bill of Rights through, for example, the Uniform Code of Military Justice, whenever it fears citizens are conspiring against it, Congress magically can claim the power under the constitution to seize and imprison citizens without indictment, without trial, indeed without any judicial process at all! How wonderful Chase’s logic is, for tyrants.

Having presented his argument first in terms of rhetorical questions, Chase next claimed the argument had judicial validity. He went at it this way:

“Congress has the power to declare war. It has, therefore, the power to provide by law for carrying on war. This power necessarily extends to all legislation essential to the prosecution of the war.”

“We (the minority) by no means assert that Congress can establish and apply the laws of war where no war had been declared or exists. Where peace exists the laws of peace (the Bill of Rights, for example) must prevail. What we do maintain is, that when the nation is involved in war, and it is exposed to invasion, it is within the power of Congress to determine in what states such great and imminent public danger exists as justifies the authorization of military tribunals for the trial of crimes against the security of the army or against the public safety.”

|

That this is the rule, can easily be seen by reading the Supreme Court’s opinions which have sanctioned the Government’s military imprisonment of thousands of Southerners during the ten years it ruled the Southern states as conquered territory, its opinions sanctioning the Government’s military imprisonment of hundreds of thousands of Japanese-American citizens in World War II, and the long line of reported decisions—from the federal district court, to the courts of appeal, to the Supreme Court and back again—that track the game the President of the United States played with the petty Chicago gang-banger, Jose Padilla; as like jumping jacks, the President skipped his minions back and forth between the laws of peace and the laws of war until, in the end, he abruptly waved a hand and abandoned the game as it finally was coming to public light. Though, in Padilla’s case, unlike in Milligan’s, the Congress authorized the game. And the United States Supreme Court approved it with a tweak.

|

No Court Has Said it Better than the Court of 1868

The Supreme Court’s opinion in Ex Parte Milligan is the clearest lecture on the limits of their civil rights, ordinary citizens should expect to ever get from the courts. The opinion, pro and con, provides the clearest picture of the alternatives the people have—either the Bill of Rights rules in all times, or it is extinquished, more or less, by the power of the government to wage war. The power to suspend, Chief Justice Chase correctly said, stems for the power to declare war. Exercising the power involves the laws of war which supplant the laws of peace for the duration.

One point above all: It is the Congress, not the courts, not the President, that decides whether it will be one way or the other. The best the courts can achieve, when Congress chooses to suspend the Bill of Rights by its power to make war, is to qualify the power with at least a little process. (See Hamdan, trial lawyer’s notebook.)

Where the rule takes us, can’t be made any plainer than the present circumstances: Even when there is no threatened invasion and no rebellion, American citizens can be seized by the military and tried for crimes by military commission, on the pathetic pretense that our Armed Forces are battling a rag-tail crowd of fervent Muslims, who are succoring terrorists, in a desolate, lawless wilderness thousands of miles from our shores.

Final Remarks

|

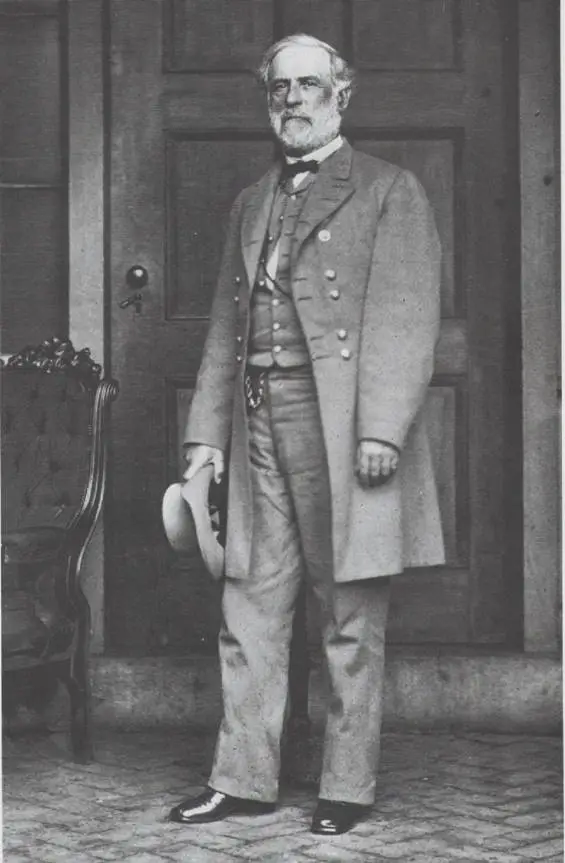

George Washington and his fellow rebels resisted British Government for ten years, finally prevailing in their overthrow of it, when, by chance, the French Navy arrived at the entrance of Hampton Roads just in time to block the British Navy from supplying Cornwallis’s army at Yorktown. General Lee would not be so lucky, and he didn’t expect to be.

Nine days after the Ex Parte Milligan decision was announced, Lambdin Milligan was at his home in Indiana. The City of Huntington received him with an ovation of welcome, cannon blasts, marching bands, and a speech by the mayor. Milligan returned to the practice of law. In an attempt to gain some stamp of righteousness over the wrongness of the Government’s conduct toward him, he filed a civil suit, in 1868, against the whole cast of characters responsible for his military imprisonment.

The Indiana Legislature had passed a law that placed a limit of five dollars on the amount of damages Milligan could be awarded. The jury gave him that amount. Today, Jose Padilla, the petty criminal from Chicago, now another classic example in American history of how the United States Government can use the power of war to kick its citizens around, has filed a similar lawsuit against the President’s men, seeking one dollar in damages.

|

Jose Padilla

As for us, the latter-day Americans, if we keep in mind anything the Supreme Court has said over the last one hundred and fifty years, it should be the words of Mr. Justice Davis, who saw into the darkest recesses of Lincoln’s mind and shivered.

“This nation cannot always remain at peace, and has no right to expect that it will always have wise and humane rulers, sincerely attached to the principles of the Constitution. Wicked men, ambitious of power, with hatred of liberty and contempt of law, may fill the place once occupied by Washington and Lincoln; and if this right [of suspension] is conceded, and the calamities of war again befall us, the dangers to human liberty are frightful to contemplate.”

The United States Supreme Court Today

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg proves the Best of the Lot;

only she urged the acceptance of Jose Padilla’s case

.

III

The Secession of Virginia

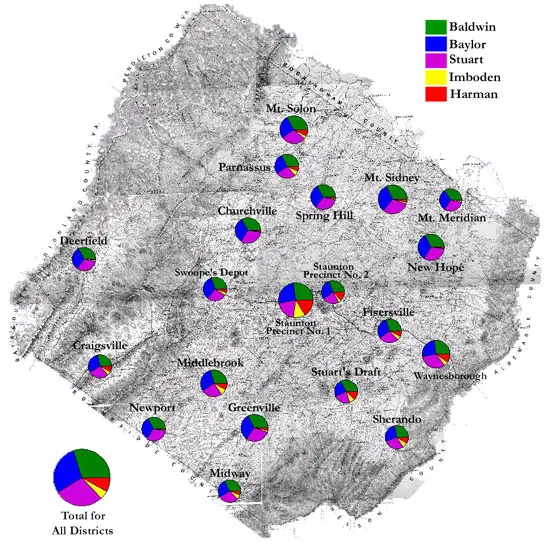

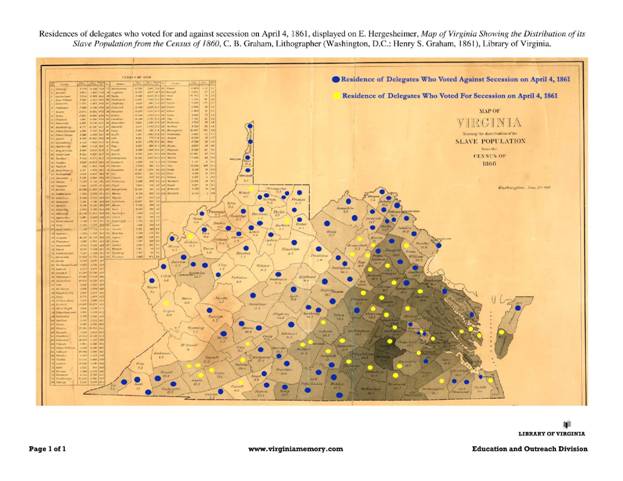

On February 4, 1861, the voters in each county of Virginia went to the polls to select their delegates to the state convention called by Governor John Letcher to consider the issue of secession. The ballot included the question whether a majority vote of the delegates was sufficient to take Virginia out of the Union, or whether they were merely to recommend it, secession depending in the end on ratification of the convention’s recommendation by a popular referendum. The voters answered, by a two to one margin, that a popular referendum was required to ratify a recommendation of secession.

Augusta County (20.2 enslaved) elected H.H. Stuart,

John Baldwin, Peter Baylor, Unionists

One hundred and fifty-two delegates assembled in Richmond on February 13 and began a debate that lasted until April 17. Back and forth, those pushing secession and those resisting it battled with words for over seven weeks. Among the most prominent of these white men, mostly lawyers, mostly slaveholders, was Jeremiah Morton, a past U.S. congressman, who owned several plantations in Orange County (49.8 percent enslaved). On February 28, he made a ringing speech for secession.

“Our soil has been invaded; our rights have been violated; principles hostile to our institutions have been inculcated in the Northern mind and ingrained in the Northern heart, so that you may make any compromise you please, and still, until we can unlearn and unteach the people, we shall find no peace.

Mr. President, by the election of Mr. Lincoln, the popular sentiment of the North has been placed in the Executive Chair, of this mighty nation:a man who did not get a single electoral vote south of Mason and Dixon’s line, a man who was elected purely by a Northern fanatical sentiment hostile to the South.

Men in every branch of the business of life do not know how to shape their contracts because of the agitation every four years of this never-dying question of slavery—I say, I want to see this question put to rest, not where it will spring up to disturb my children and involve them in utter ruin twenty or thirty years hence; but I want to put it where it never will disturb my descendants—for if there is to be bloodshed, and this question cannot otherwise be settled, I would rather give the blood that runs through my veins. . . “

On March 4, the day of Lincoln’s inauguration, Waitman Willey, representing Monogalia County (0.8 percent enslaved), in the extreme northwestern edge of Virginia, answered Morton, for the Unionists.

“The remedy proposed by the gentlemen on the other side is secession, but I never shall believe that Washington brought the States together without any bond to bind the Union.

But you over there say the Republican party threatens to exclude the South from the common territory. As to this I have said I will never submit to it. But what danger is there of our rights being invaded? Has not the Supreme Court decided to guarantee, to the full extent, the right of every slaveholder in the land to carry his property into all the territories of the United States? (In Re Dred Scott, 1856) But suppose there were no such decision, and we had to redress our rights in another way. I ask you gentlemen to point out to me, how are we to acquire our equal rights in the territories, by seceding, by turning our backs on those territories, by giving up our rights to share in those territories?

I am not here to defend the election of Abraham Lincoln. I believe his election was a fraud, nominated as he was by a sectional party, and upon a sectional platform. But he was nominated and elected according to the forms of law.

I say, sir, that a dissolution of the Union will be the commencement of the abolition of slavery, first in Virginia, and ultimately throughout the Union. Will it not, sir, make a hostile border for Virginia, and enable slaves to escape more rapidly? Will it not, virtually, bring Canada to our doors? The slave will know that when he reaches the line he will be safe; and escape he will. The owners of slaves will either move themselves further south, or they will sell their slaves south, which in either case will push slavery further and further south until it is swept from the country. That is what they say, don’t they—Charles Sumner and Lloyd Garrison? They want to surround the slave states “with a belt of fire.” Let the Union be dissolved and the slave states will be hemmed in by a cordon of hostile elements.

But it is said the Union is already dissolved. I think not, sir. The Union still lives, and will live while Virginia stands firm. Let her stand where she ever stood, and this Union can never be permanently dissolved. Some of the states may secede, but they will be like asteroids flung off from the sun. But, sir, the sun still shines. The Union still remains while Virginia is steadfast.”

Willey’s speech was followed by speeches from more Unionist delegates, including among them John Carlile’s (Harrison County 4.2 percent enslaved); George Brent’s (Alexandria 11 percent enslaved); and George Summer’s (Kanawha Country 13.5 percent enslaved). On March 16, as Lincoln was battling Seward for control of the government’s policy, this string of pro-union speeches was broken by George Wythe Randolph’s (Thomas Jefferson’s youngest grandson).

“Take the history of abolitionized governments,” he said; “it is the history of abolitionized people. Look at England, France, Denmark. Look at Russia. Abolition mounts the throne and serfdom disappears. What right have we to expect better things from our Government? Will the Constitution restrain it? Abolition will soon have the power to make that what it pleases. The whole argument against the extension of slavery is soon by a very slight deflection, made to bear against the existence of slavery and thus the anti-extension idea is merged in that of abolition. With such views held by the chief Executive, the dispenser of patronage, must we wait for an overt act—must we stand until the bayonet is at our throats?”

More secessionist speeches followed Randolph’s, the emotion in the assembly hall rising and falling as each speaker confronted shouts and interruptions from the other side. Then toward the end of March John Baldwin, a slaveholder from Augusta County (20.2 percent enslaved) stirred the delegates to a fever pitch of passion whichever side of the issue they rested.

“Sir, in regard to the question of slavery, I have always entertained the opinion that African slavery, as it exists in Virginia, is a good thing, a blessing alike to the master and the slave. I have no objection that this mild institution may cover the whole earth.

The election of Lincoln has been spoken if as an overthrow, or a subversion of the Constitution, by the use of its own forms. I regard this assumption, that the election of any man to the Presidency can justify disunion, as a direct assault upon the fundamental principles of American liberty. Our fathers built into the Constitution too many barriers to allow one man to usurp authority. One may fail, and yet another remains to protect the Constitution from overthrow.

Now, sir, these barriers were erected as an injunction to us, if we are to be beaten in the House, we appeal to the Senate. If beaten in the Senate, we appeal to the President’s veto. If that fails, we appeal to the Supreme Court. And, if all these means of protection have failed, we do not give up the ship, but we appeal from the false agents of the people, to their masters at the polls.