|

In the two weeks that passed after Lincoln published his

April 15 proclamation, calling upon the loyal state governors to send him

regiments of militiamen, the governors of Illinois, Indiana, Ohio,

Pennsylvania, New York and New Jersey went to their legislatures and obtained

authority to muster their militiamen into regiments for a term of three months,

and to use state funds to purchase rifles, ammunition, clothing, accruements,

wagons, horses and artillery for the use of Lincoln’s government. (At this time

Lincoln had little money in the treasury to draw upon.)

As the

men mustered into companies in their respective states, and moved to camps

where they were organized into regiments, the governors appointed general

officers to command their state forces. In New York, Governor Morgan made John

A. Dix and Charles Sandford “major-generals of state militia.” Governor

Dennison of Ohio gave the same title to George B. McClellan. Governor Curtin of

Pennsylvania did the same with Robert Patterson. Massachusetts Governor

Andrews gave this rank to Benjamin Butler and Nathaniel Banks, and Governor Sprague

of Rhode Island gave it to Ambrose Burnside. As the

men mustered into companies in their respective states, and moved to camps

where they were organized into regiments, the governors appointed general

officers to command their state forces. In New York, Governor Morgan made John

A. Dix and Charles Sandford “major-generals of state militia.” Governor

Dennison of Ohio gave the same title to George B. McClellan. Governor Curtin of

Pennsylvania did the same with Robert Patterson. Massachusetts Governor

Andrews gave this rank to Benjamin Butler and Nathaniel Banks, and Governor Sprague

of Rhode Island gave it to Ambrose Burnside.

In Washington, President Lincoln, through his agent, Lieutenant

General Winfield Scott, the Regular army’s general-in-chief, made these state

militia general officers “major-generals of volunteers.” Scott, with Lincoln’s approval, divided the territory covering the loyal states bordering on the Potomac and Ohio rivers into “departments,” and placed these officers in command of them:

McClellan was assigned command of the Department of the Ohio, which eventually

came to include Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky and western Virginia. Patterson was

assigned the Department of Washington which included Pennsylvania and Delaware. A few weeks later, Patterson was switched to the “Department of Pennsylvania,”

and John Mansfield, a colonel in the Regular army, took command of the

Department of Washington, now limited to the District of Columbia. Dix was

assigned recruitment duty in New York City. Butler was assigned the Department

of Maryland, including Baltimore, then, replaced by Massachusetts militia

general, Nathaniel Banks, he was moved to Fort Monroe. Charles Sandford was placed

in command of the New York regiments which, by the middle of May, constituted

the largest state force encamped at the Capital and would be the first to

invade Virginia.

By May 3, having been bombarded by the loyal state governors

to muster more men into service, Lincoln realized that he could abandon all

pretense of acting in conformance to the Constitution. He had restricted his

first call for troops to a three month term of service in order to conform to

the restrictions imposed upon the President by the Militia Act of 1795, which ,

in section 2, specified that, “whenever the laws of the Union shall be opposed

in any state by combinations too powerful to be suppressed by ordinary means,

it shall be lawful for the President to call forth the militia, and the use of

the militia may be continued until the expiration of thirty days after the

commencement of the then next session of Congress.”

|

Lincoln had purposely chosen July 4th as the day

for the special session of Congress to convene, to give himself time to bring

the Army into existence, depending upon unfolding events to convince the

Congress to continue the war he had created. Now, with the response from the

governors so uniformly supportive of his initial action and their clamor rising

for the mustering of more troops, he knew the likelihood slim that the Congress

would repudiate his actions. So, with an eye on the coming secession referendum

in Virginia, he decided to get moving with military offensive actions, which

required volunteers committed to long term enlistments.

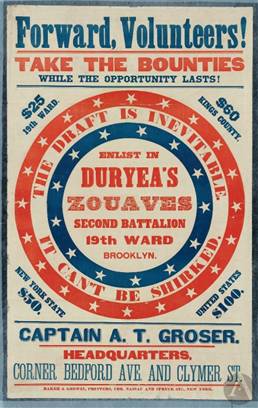

Thus, on May 3, he published the following call, based on

nothing at all but the gamble he would not be impeached in July.

Whereas existing exigencies (i.e.,

“necessity”) demand immediate measures for the protection of the National

Constitution and the preservation of the Union. . . to which end a military

force (for offensive operations) appears to be indispensably necessary I call

into the service of the United States 42,034 volunteers, to serve for a period

of three years, plus men enough to fill eight new regiments in the Regular

army.

The Governors instantly respond to Lincoln:

Governor Curtin: “We have more than the requisition of

troops called by you, now in the field. The Legislature has authorized the

formation of twenty-five additional regiments as Pennsylvania’s reserve and has

granted the necessary funds to support them.”

Governor Olden, of New Jersey: “Four regiments start

tomorrow.”

Governor Andrews of Massachusetts: ten thousand drilling,

hoping for call.”

Governor Fairbanks of Vermont: “Two regiments waiting for

orders.”

Governor Buckingham of Connecticut: “One regiment ready.”

Governor Sprague of Rhode Island: “One regiment and a field

battery ready.”

Governor Washburn of Maine: “Four regiments nearly ready.”

Governor Dennison of Ohio: “Twenty-two regiments in camp,

under drill; Legislature has approved $3 million.”

On May 6, Governor Randall of Wisconsin wrote Lincoln:

“The governors of several of the states

met on Friday last, at Cleveland. We make you these suggestions: We must

control the business of the Mississippi and the Ohio. There is a spirit invoked

by this rebellion among the liberty-loving people of the country that is

driving them to action and if the government will not permit them to act for

it, they will act for themselves. It is better for the government to direct

this current than to let it run wild. There is a conviction of great wrongs

to be redressed. If the government does not act at once there will be a war

among the Border States. Call for three hundred thousand. These states cannot

be satisfied with call after call for raw troops. They would not be soldiers

but marks for the enemy to shoot at. We want authority to put more men in the

field.”

The

Problem of the Three Month Men

|

In

response to the governors’ enthusiasm, Lincoln, through Simon Cameron,

Secretary of War, encouraged them to induce the three month volunteers, still

in state camps, to muster, or remuster as the case may be, into United States service for three years. Governor Curtin, of Pennsylvania, wired Cameron in

reply: “I have prepared a circular to be sent to the colonels embracing the

suggestion of your dispatch. On May 13, Cameron wired Curtin: “How many

regiments that have been mustered into service for three months are willing to

be remustered for three years?” The next day Curtin answered: “Keim’s division

of six regiments would not go for three years. No regiment as yet mustered in

for three years.” Cameron replied to this with, “Ten regiments are assigned to Pennsylvania under second call, for three years service.” Curtin responded on May 20:

“Patterson claims that his entire division has been mustered into service as

three month men. An order was issued by me on April 17th, directing

Patterson to march his division at once. Patterson claims that, under this

order, the seven regiments of the division were mustered in.”

Upon Lincoln’s first call, the Pennsylvania Legislature was

not in session. Governor Curtin, on his own authority, called for 25,000 men.

Cameron refused to accept all of them, as the number exceeded the quota then

assigned. Curtin then called the Legislature into session and it passed an act

authorizing the organization of fifteen additional regiments into the Pennsylvania

Reserve Corps. These troops as they came into camp were then sworn into the

service of the State and were subject, under the state law, to the call of the

National Government. |

The Problem of

Who Commands Who

Up to the time of Lincoln’s call for three year volunteers,

he allowed all the officers, whatever their rank, to be appointed by the

governors. After the call, he specified that the commissioned officers of the

company and regiment levels were to be appointed by the governors or by the men,

but the general officers only by him. The force of three year volunteers was to

be organized into three divisions, each composed of from three to four

brigades, and each brigade to have four regiments. Each division was to be

commanded by a major-general and each brigade by a brigadier-general. In this

way, Lincoln cut the governors out of the chain of command between himself and

the troops in the field; henceforth, the governors could not give orders to the

generals and the company and regimental officers could take orders only from

the generals. Lincoln now had his hand firmly on the throttle.

The Problem of Choosing

a Strategic Plan of Operations

Lincoln’s purpose, in making his second call, was to use the

42,000 three year volunteers as the core of an army to operate against the

Confederate army assembling at Manassas Junction. Though he knew the military

forces gathering in Virginia intended to act on the defensive, he meant to

attack them as soon as he could assemble an army capable of taking the field

against them—as soon as the people of Virginia ratified the Ordinance of

Secession, that is.

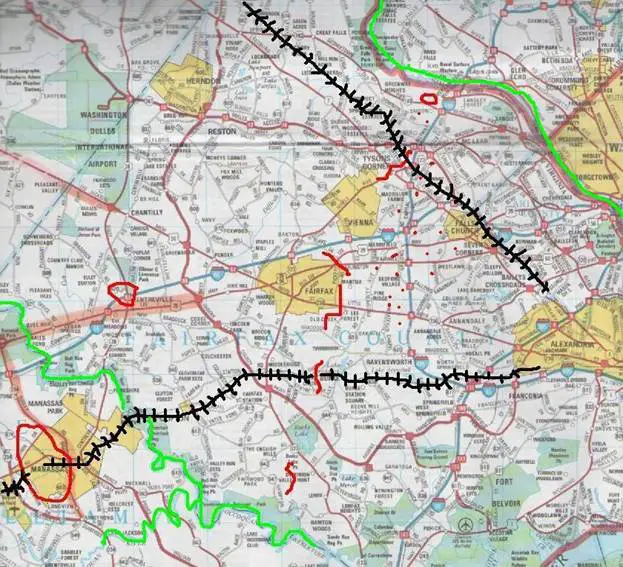

Confederate detachments were then occupying a defensive line,

trying to block Lincoln’s invasion, that would eventually stretch from the Potomac at Vienna, cutting the Loudoun & Hampshire Railroad, south through Fairfax

Courthouse, cutting the Orange & Alexandria Railroad, to the Occoquan River.

But General Scott had a different idea.

On May 3, the day Lincoln published his second call, 74 year

old General Scott wrote to 34 year old George McClellan, disclosing what he was

thinking:

|

“It will not be prudent to rely on the

three month men for offensive operations as their term of service will expire.

We must rely greatly on a blockade (Lincoln, at Scott’s behest, had proclaimed

a blockade late in April). I propose a movement down the Mississippi. We will

need twenty gun boats, forty steamers, and sixty thousand men. It is probable

you will be invited to command this army. The great danger to this plan is the impatience

of our Union friends (read Lincoln). They will be unwilling to wait for the

slow instructions, for the rise of the rivers, for the return of the frost.” A

few days later, he wrote again to McClellan, to say: “I proposed to establish

an army of regulars, say 80,000, to be divided into two columns, to clear the Mississippi to the Gulf.” |

General

Scott has been, for the most part, forgotten by this generation of Americans.

Those who know his name think of him as old, feeble, barely able to move,

which, of course, by 1861, he was. But his writings show that his mind was

still sharp, filled with the knowledge and experience gained from almost fifty

years military service, and which included his organizing and commanding the

little American army (the core of which were regulars) that invaded Mexico, in

1846; marched 600 miles into her interior and, six months later, brought her

government down, forcing a treaty that doubled the size of the territory of the

United States.

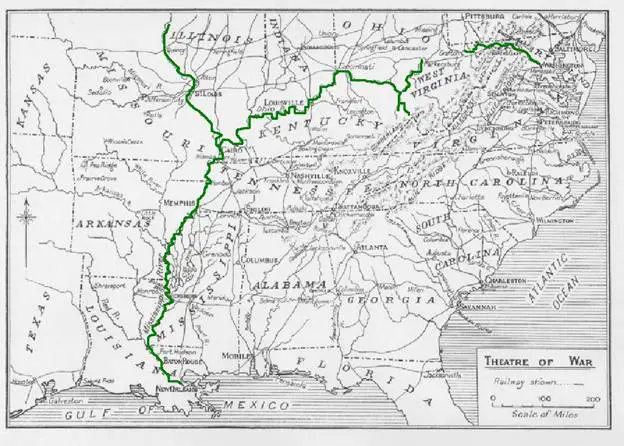

The Theater of

the War

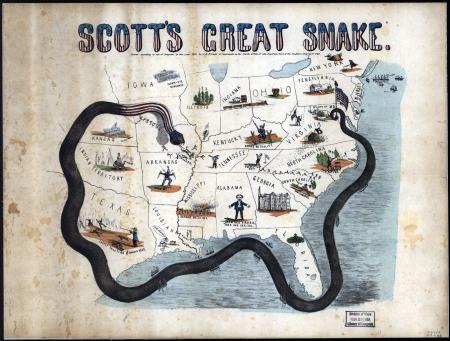

General Scott understood clearly that conquering the

Southern States by war would not happen quickly; rather than the war ending

with a grand battle like Waterloo, it would end, he knew, in the economic

strangulation of the country—one way or another. The strangulation could happen

two ways—by armies fighting armies across its breadth, or by a military

blockade that sealed the country from the world. By either method it would take

years to conquer the South, but the latter method would be less destructive of

the people and infrastructure of the South, making a durable peace more likely

to take hold quicker. So General Scott, a native born Virginian, thought.

Scott’s strategic vision was focused on taking immediate

control of the navigation of the Mississippi which would cut off Missouri, Arkansas, Louisiana, and Texas from the Confederacy, and would lead to the occupation

of Memphis, Vicksburg, and New Orleans. Meanwhile, the naval blockade would, in

large measure, eventually prevent the Confederacy from receiving substantial

support from the seas. Only after time had allowed a huge army of drilled

regulars to develop, would an advance be made into the depths of the South.

With the wide river of the Ohio making it practically

impossible for the Confederacy to retaliate against Illinois, Indiana, and

Ohio, backed as they were by Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan, it’s only

choice would be to direct its military energy toward Pennsylvania where it

would face the combined forces of that State, New York, New Jersey, and New

England. If the Confederacy were to take the offensive against the North, as

far as Scott was concerned it would be battering itself against an impenetrable

wall while it exhausted its supplies.

But though he seemingly listened to Scott initially, Lincoln had, in his mind, a quite different approach. He was not willing to take what

seemed to him an approach that had no certain end at a definite

time and which left the North sitting on its hands—something he could not

afford politically to do. His strategic vision was to use the great

numerical strength in men and material that the North enjoyed, to

crush the South’s resistance to his rule as fast as the men could be

organized into armies and march into the heartland of the Confederacy. In his

mind, the more territory he could seize and hold, the more evidence he

could show the Northern people and the world that his government was winning;

and thus induce the people to endure the war, and the world not to take the

Confederacy’s side. And as long as the North endured and the world did not give

the South military support, Lincoln was certain the rebel states could not

escape the Union’s grasp.

Lincoln’s

General Strategic Idea: “Cut em to Pieces”

The West Point

Graduates Scramble For Rank

From all over the Union they came: McClellan quit his

position as a railroad president, and seized the chance to command the Ohio

State Militia; Grant, employed as a shopkeeper in Galena, Illinois, coming

under the wing of Illinois Governor Yates, gained command of the 21st

Illinois volunteer regiment and went into camp with it at Springfield; Sherman,

employed as president of a military college in Louisiana, resigned and hurried

to Washington, where his brother, John Sherman, U.S. Senator from Ohio,

introduced him to Lincoln, which netted him a commission as a colonel in the

Regular army and got him a place on General Scott’s headquarters staff; Ambrose

Burnside, employed as a cashier with the Illinois Central Railroad, took

command of the Rhode Island Militia and, by May, was in Washington with two

regiments and an artillery battery. John Fremont, returning from Europe, was in Washington by late May, looking for a slot at the major-general level. Henry

Halleck, practicing law in San Francisco, gained command of the California

State Militia and would eventually become a major-general in the Regular army,

rising by 1862 to the position of Lincoln’s general-in-chief. And Joe Hooker, employed

in California as a poor rancher, set sail for Washington in May with $700 in

his pocket.

Then

there is the special case of forty-three year old Major Irvin McDowell. By the

beginning of May, thinking offensively, Lincoln had set his Secretary of the

Treasury, Salmon Chase, and his Secretary of War, Simon Cameron, to work with

the loyal state governors, to find the money to pay for the cost of bringing

the volunteers into his service, and to get the volunteers to Washington and Cincinnati. In performing their work, both secretaries came in personal contact with

McDowell, who as a member of Scott’s staff was acting as the mustering officer

for the District of Columbia’s militia. As a consequence of his position,

McDowell became responsible for organizing the militia into regiments. As the

loyal state regiments arrived at Washington, they came within his command and Lincoln took notice of him, the two men having been introduced by Chase. Then

there is the special case of forty-three year old Major Irvin McDowell. By the

beginning of May, thinking offensively, Lincoln had set his Secretary of the

Treasury, Salmon Chase, and his Secretary of War, Simon Cameron, to work with

the loyal state governors, to find the money to pay for the cost of bringing

the volunteers into his service, and to get the volunteers to Washington and Cincinnati. In performing their work, both secretaries came in personal contact with

McDowell, who as a member of Scott’s staff was acting as the mustering officer

for the District of Columbia’s militia. As a consequence of his position,

McDowell became responsible for organizing the militia into regiments. As the

loyal state regiments arrived at Washington, they came within his command and Lincoln took notice of him, the two men having been introduced by Chase.

Realizing that he and Scott entertained divergent views of

military strategy, and that Scott would resist his wishes, probably using his

control of the officer corps as a device to neutralize him, Lincoln decided to

make McDowell his boy, by offering him a commission as brigadier-general in the

Regular army. |

II

Lincoln Invades Virginia

If You Can Kill

Virginia, You Can Kill The Confederacy

The New York

Times

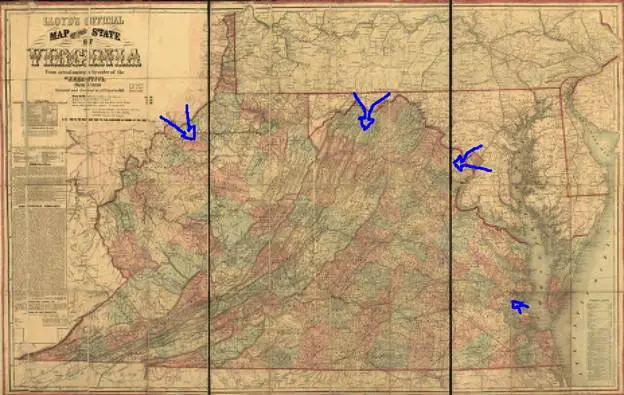

As soon as the people of Virginia ratified their State’s

Ordinance of Secession, Lincoln began orchestrating movements of military

forces into Virginia. At Washington, New York State Militia Major General,

Charles Sandford, led a force of New York and Rhode Island Volunteers across

the three bridges linking Washington with Virginia and occupied the city of Arlington and the Lee family plantation on Arlington Heights, making the Lee family

mansion his headquarters.

In the course of this, Lincoln suffered his first personal

loss of the war. Colonel Elmer Ellsworth, of the Eleventh New York Regiment—the

“New York Fire Zouaves”—was shot and killed, when he barged into a private house

in Alexandria and charged up a flight of stairs to rip down a Confederate flag

flying on a pole from the roof. (On the way up the stairs, a man stepped from a

room and shot him dead.) Ellsworth’s corpse was carried to the White House and

placed in the East Room, as Lincoln stood over it, in tears; crying, “My boy!

My boy!” Thus, you reap what you sow.

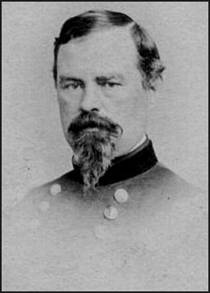

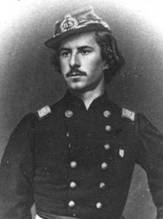

Pennsylvania State Militia Major General Robert Patterson (also

commissioned, like Sandford, a major-general of volunteers by Lincoln) began

assembling a force of seventeen regiments of Pennsylvania three month

volunteers at Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, to invade the Shenandoah Valley,

occupy Harper’s Ferry, and move on Martinsburg where the repair shops and train

sheds of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad were located. Though not a West Point graduate, Patterson had been a general officer in the U.S. Army, and had acted

as General Scott’s second-in-command for a short time during the War with Mexico. The same age as Scott, Patterson was assumed to be the right man to carry the war

into the Valley.

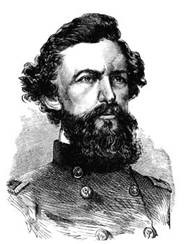

Patterson in 1847 |

Patterson

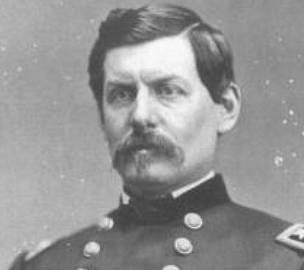

in 1861 |

Benjamin Butler, who had been replaced by Nathaniel Banks

after occupying Baltimore with troops early in the month, was at Fort Monroe with Massachusetts troops. He would do nothing but hold the fort.

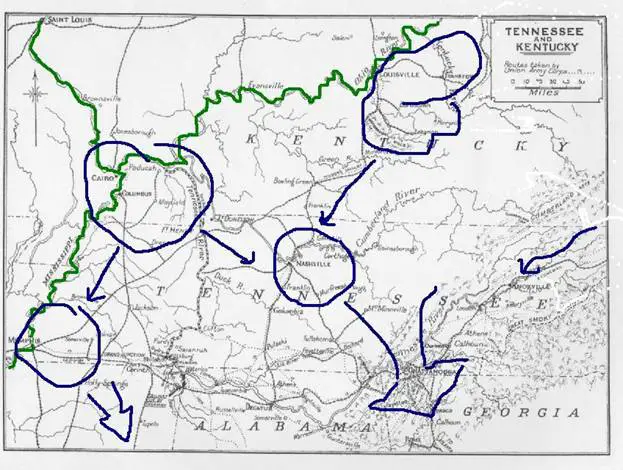

George

McClellan, commissioned by Lincoln a major-general in the Regular army late in

May, had spent the early part of the month, promoting himself, by writing

personal letters to Lincoln, Chase, Cameron, and Scott, proposing one plan of

operations for his troops after another. First, he proposed that 80,000 men be

assigned to his department for a movement across the Ohio River, to move south

through the valley of the Great Kanawha and toward Richmond. A fanstasy

everyone knew. The next plan he offered, was to move his proposed army into Kentucky and march on Nashville, and then head for Alabama and Georgia. When these plans

reached Lincoln’s desk and he expressed interest, General Scott dismissed them

on the ground that they entailed overland marches that would break down the men,

their horses and wagons. Rather than attempt to subdue the Confederacy, piece

meal, Scott tried to convince Lincoln, it should be enveloped—by establishing a

cordon of posts on the Mississippi down to its mouth, and by blockading the

seaboard with warships. But Lincoln would have none of it, appointing McClellan

the first regular army major general with the expectation that, like McDowell

in the East, Mac would be his boy in the West. George

McClellan, commissioned by Lincoln a major-general in the Regular army late in

May, had spent the early part of the month, promoting himself, by writing

personal letters to Lincoln, Chase, Cameron, and Scott, proposing one plan of

operations for his troops after another. First, he proposed that 80,000 men be

assigned to his department for a movement across the Ohio River, to move south

through the valley of the Great Kanawha and toward Richmond. A fanstasy

everyone knew. The next plan he offered, was to move his proposed army into Kentucky and march on Nashville, and then head for Alabama and Georgia. When these plans

reached Lincoln’s desk and he expressed interest, General Scott dismissed them

on the ground that they entailed overland marches that would break down the men,

their horses and wagons. Rather than attempt to subdue the Confederacy, piece

meal, Scott tried to convince Lincoln, it should be enveloped—by establishing a

cordon of posts on the Mississippi down to its mouth, and by blockading the

seaboard with warships. But Lincoln would have none of it, appointing McClellan

the first regular army major general with the expectation that, like McDowell

in the East, Mac would be his boy in the West.

McClellan knew how to flatter: on May 9, when it became

apparent to him that General Scott was not pleased with his end-around communications

with politicians, he sent Scott a long personal letter full of bull: “The first

aim of my life,” he wrote, “is to justify the good opinion you have of me, and

to prove that the great soldier of our country can not only command armies

himself but teach others to do so. I do not expect your mantle to fall on my

shoulders, but I hope it will be said I was a worthy disciple of your school.” At

the same time, the two-faced jerk was writing Ohio Governor William Dennison:

“The apathy in Washington is very discouraging . . . they are entirely too slow

for such an emergency and I almost regret having entered upon my present duty.”

And, a few days later, he wrote this to Dennison: “General Scott is eminently

sensitive, and does not take suggestions kindly from subordinates, especially

when they conflict with his preconceived notions.” He was already angling to

undercut Scott and slip into his place.

On May 24, the day following the No vote on secession by twenty-five

of the counties in northwestern Virginia, Lincoln through Scott sent McClellan

the message that he wished him to move into Virginia. Scott wrote McClellan: “We

have information Virginia troops have reached Grafton (a point on the B & O

Railroad). Can you counter it? Act promptly.” The next day, from his

headquarters at Cincinnati, McClellan sent orders to several regiments posted

at Parkersburg and Wheeling, to move up the spurs of the B & O Railroad and

drive the rebels away from Grafton.

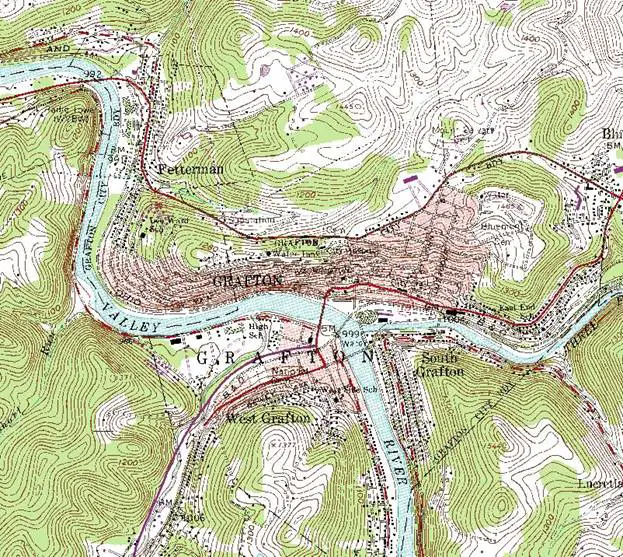

Grafton

Railroad Crossing

May 27, 1861

Lieut. Gen. Winfield Scott:

Two bridges burned last night near Farmington, on the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. Have ordered the First Regiment West

Virginia and one Ohio regiment to move at once by rail from Wheeling on Fairmont, occupying bridges as they go. Two Ohio regiments ordered to occupy Parkersburg and move toward Grafton.

GEO

B. McCLELLAN, Major-General

General McClellan was off and running in the Virginia hinterland. Irvin McDowell, on the other hand, was now front and center; having

been promoted by Lincoln to brigadier-general in the Regular army, Lincoln used the promotion to induce McDowell, over General Scott’s objection, to assume

command of the new Department of Virginia, supplanting New York State Militia

General Sandford. McDowell arrived at Lee’s mansion at Arlington Heights on May

29. Immediately he ordered the regiments that were there to be organized into

three brigades and placed them under the newly promoted Regular army colonels

ordered to report to him. Then he wrote to General Scott’s adjutant.

May 29, 1861

Colonel:

I am aware we are not, theoretically

speaking, at war with the State of Virginia, and we are not here, in an enemy’s

country; but since the courts are not functioning, should not cases of

depredations be handled by military commission as similar cases were in Mexico? It is a question of policy I beg to submit to the General-in-Chief. The plea that a

man is a secessionist is set up by the depredators as a justification for their

acts. (precedent for Mr. Yoo)

Irvin

McDowell, Brigadier-General commanding

Then he wrote a letter to Mrs.

Lee.

Hdqs.

Department of Northeastern Virginia

Arlington, May 30, 1861

Mrs. R.E. Lee:

MADAM: I am here temporarily in camp on

the grounds, preferring this to sleeping in the house. I assure you it has been

and will be my earnest endeavor to have all things so ordered that on your

return you will find things as little disturbed as possible. Everything has

been done as you desired with respect to your servants, and your wishes, as far

as possible have been complied with. I trust, Madam, you will not consider it

an intrusion if I say I have the most sincere sympathy for your distress, and I

shall be always ready to do whatever may alleviate it.

IRVIN

McDOWELL

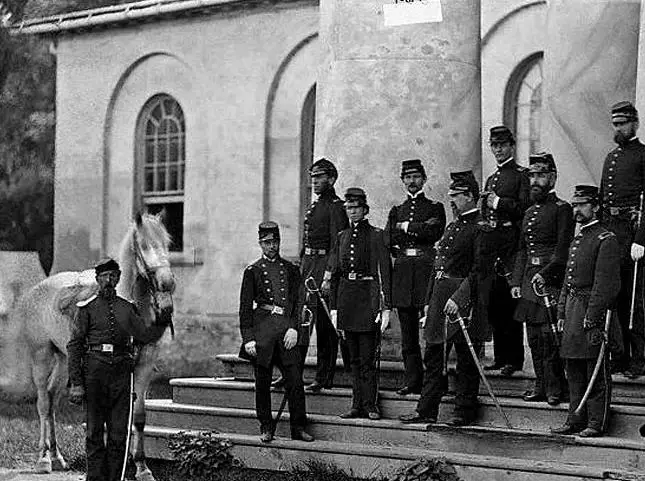

McDowell

and Staff on the Steps of Mrs. Lee’s Home

III

The World Sits Back and Waits

In early May, Lord John Russell, British Secretary of State,

announced in the House of Commons that a British naval force had been

dispatched to the coast of the United States, to protect English commercial

interests; and that France and Great Britain had agreed to take the same course

of recognition of the Confederate Government. At the same time, he received

Confederate ambassadors, in the manner in which Secretary of State William

Seward had received them in Washington earlier. Learning of this from Charles

Francis Adams, the United States Ambassador to Britain, Seward wrote

instructions.

|

“As to the blockade, you will say that

by our own laws and the law of nations, this government has a clear right to

suppress insurrection. An exclusion of commerce from national ports which have

been seized by insurgents is a proper means to that end and, thus, we expect

the blockade to be respected by Great Britain. If it doesn’t, a war may ensue

between the United States and one, two, or even more European nations. Great Britain has but to wait a few months, and all her present inconveniences will cease

with all our own troubles.”

Seward is kidding. According to the law of nations, as it

existed at the time, a blockade such as Lincoln had proclaimed was permissible

only between belligerents, not between a government and what it deemed

to be insurgents. The purpose of a blockage is to isolate and weaken an enemy.

That this may be done effectively, the merchant ships of neutral nations may be

stopped and searched on the high seas, and in case they carry contraband, or

are bound for a blockaded port, they may be seized and brought before a prize

court for condemnation. Similarly, the enemy may, under the law of nations,

resort to the measure of using privateers on the high seas for the same

purpose. Such conduct, under the law of nations, is lawful only in time of war.

As a result of the two American governments’ positions—the one blockading, the

other privateering—Lord Russell counseled the Queen that the British Government

was bound to recognize that they were both entitled to claim the rights, and be

responsible for the obligations, of belligerents. (Something our government

still doesn’t accept; it calls something war but ignores the obligations.) |

Queen Victoria

In consequence, on May 13, the Queen of England proclaimed

that she recognized a state of war existed between Lincoln’s government

and Davis’s, and that therefore both were entitled to belligerent rights.

Within a week France, Spain, and the Netherlands followed Britain’s lead.

As Lord Russell told Adams, the reality was that eight

million citizens of the Confederacy were in open revolt against Lincoln’s government. “It is not our practice,” Russell said, “to treat eight million free

men as pirates and to hang their sailors if they attempt to stop our merchant

ships. It seems to me that you have expected us to discourage the South. How

this is to be done, except by waging war against it, I am at a loss to

imagine.”

William Seward answered this with an Alice-in-Wonderland

concoction: “We shall never admit that Great Britain and France have recognized the insurgents as a belligerent party. You say you have declared it.

We reply, `but not to us.’ You rejoin: `The public declaration of the Queen

concludes the fact.’ We, nevertheless, reply: ‘It must be not her declaration,

but the fact, that concludes the fact.’”

On May 21, Lord Russell told the Confederate ambassadors

that Great Britain would recognize the Confederate Government as legitimate,

as opposed to belligerent, upon the first decided Confederate

success. Napoleon III told the ambassadors when they reached Paris that France would follow Britain’s lead. The threat, which Adams reported, did not dissuade Lincoln from rushing his people into the abyss.

IV

The People Waive Their Civil Liberties

The New York

Times

May 29, 1861

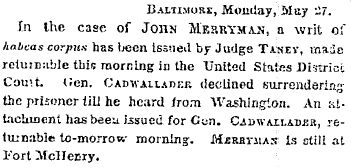

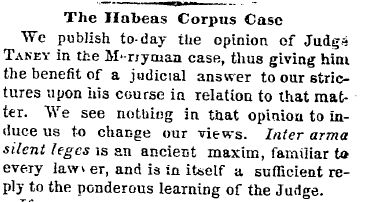

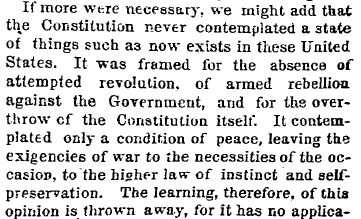

Chief Justice

Roger Taney

“It is the fuction

of judges to apply the law,

not teach

morality or preach religion”

Joe Ryan |