|

Flames Beyond Gettysburg certainly does

deserve a place in the Gettysburg library of any serious judge of the facts

underpinning the Gettysburg Campaign. Written by Scott L. Mingus, Sr., the book

provides a well-written picture of the Confederate advance into Pennsylvania, beginning with Richard Ewell’s corps reaching Carlisle and ending with John

Gordon’s brigade of Jubal Early’s division arriving at Wrightsville. Most

importantly Mr. Mingus documents the rain fall that occurred over a period of

several days during the Confederate march, and gives close details of the

movements of the cavalry squadrons that accompanied Early and Ewell’s separate

marches toward the Susquehanna; details important to any critical analysis of

Lee’s objective in moving into Pennsylvania. corps reaching Carlisle and ending with John

Gordon’s brigade of Jubal Early’s division arriving at Wrightsville. Most

importantly Mr. Mingus documents the rain fall that occurred over a period of

several days during the Confederate march, and gives close details of the

movements of the cavalry squadrons that accompanied Early and Ewell’s separate

marches toward the Susquehanna; details important to any critical analysis of

Lee’s objective in moving into Pennsylvania.

However, in bringing these important details into clear

view, Mr. Mingus failed to seize the opportunity to use them to debunk the

historical myth that General Lee’s intent, in carrying the war into Pennsylvania, was merely to threaten the seizure of Harrisburg while sweeping up as much

moveable wealth of the State that he could, before returning to Virginia.

The missed opportunity is manifest in Mr. Mingus’s choice of

subtitle: “The Confederate Expedition to the Susquehanna River.” The

word “expedition” is defined by Webster’s to mean “a sending forth of

men on the march for some definite purpose.” As do historians and civil war

writers generally, Mr. Mingus identifies the purpose of Lee’s march into Pennsylvania to be the capture of Harrisburg, writing that Lee meant to “push well beyond Maryland into the lush Pennsylvania farmlands, forcing the Army of the Potomac to come to

[him]. [His] eyes were on targets of political and strategic importance, among

them Harrisburg.”

Mingus offers the explanation that Lee was motivated by this

purpose, because the “seizure of the capital of the North’s second most

populous state could stimulate cries for a negotiated peace and increase

European pressure on Washington.” Yet, when one uses common sense to analyze

the objective strategic situation confronting Lee and the Confederacy, in June

1863, such an explanation is easily seen to be silly indeed. For Vicksburg was

about to fall to Grant’s siege and the Northern people could hardly be expected

under such circumstance to cry for a negotiated peace; nor could the British

government—the only foreign government that mattered—seriously be expected to

exert the only meaningful “pressure” that counted, the British Navy, against

Lincoln’s now effective blockade.

Mingus hints at another purpose Lee might have had in mind

when in a throwaway sentence he writes, “Surely Hooker’s army would follow Lee.

. . . If Lee was correct (in thinking this), he could, at the time and place of

his choosing, [initiate] a pitched battle.” Shying away from analyzing

the facts in light of this quite different purpose, the author concentrates the

reader’s attention on the details of Early’s march from Cashtown to York and then Gordon’s march on to Wrightsville. In the process of this, for proof of

Lee’s motive, the story relies on the writings that obscure the objective truth

of the matter. For example, as do most historians writing about the campaign,

the author, here, refers the reader to the message that time has preserved,

sent by General Lee to Ewell on June 22, 1863, as Ewell was crossing the Potomac. “I think,” Lee wrote, “your best course will be toward the Susquehanna. . . If Harrisburg comes within your means, capture it.”

Apparently loath to separate from the pack of historians who

cling to Lee’s phrase, the author means this shopworn citation to form the

primary basis for proving the fact of Lee’s intent. Yet, given the undisputed reality

of the matter all one can say about Lee’s statement is that it was

intended to mislead the enemy in the event the courier carrying the message was

seized in route to Ewell. For everyone must agree General Lee was not stupid.

He had to know—as any reasonable person under the circumstances had to

know—that it was impossible for Ewell’s corps, much less Lee’s whole

army, to “capture” Harrisburg.

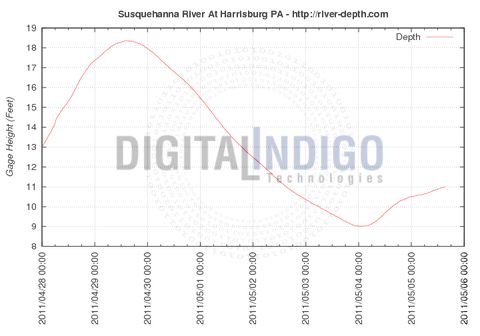

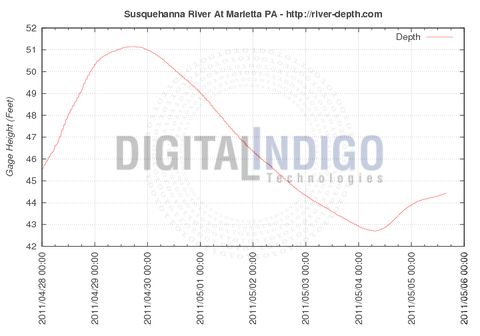

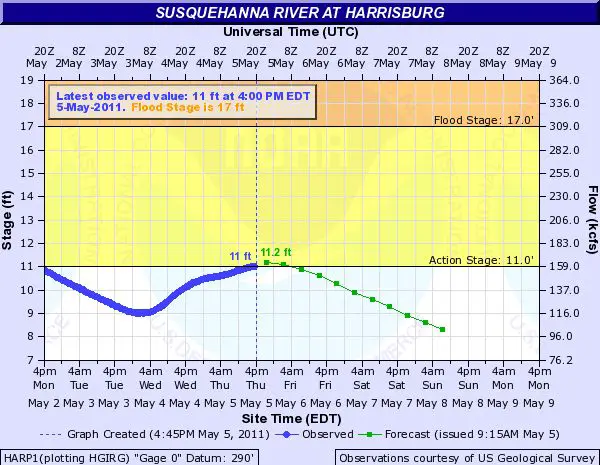

Why? Because, as Mr. Mingus must well know, the Susquehanna River, in June 1863, was impossible to cross without a bridge; and there

certainly would not be a bridge by the time either Rodes’s division reached the

river in front of Harrisburg, or Gordon’s brigade reached the river in front of

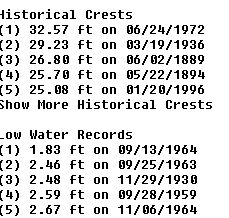

Columbia! The historical depth charts for the river at these points is available

to anyone who cares to read them.

Historically, one might wade across the mile wide river at

either point in the fall of the year, but never in the history of recorded time

during June. Mr. Mingus, in the substantial part of his book, confirms this

fact when he writes: “Gordon realized there was no alternative means for his

brigade to cross the still swollen river. The dam (some distance south

of Wrightsville) was too far beneath the surface of the water to provide

footing.” The reason, of course, for the “swollen river” was that it had been

raining off and on from June 24 through June 30, the rain, dropping on the Alleghenies

to the west, pouring into the Susquehanna. Lee knew, therefore, as early as

June 25 when he crossed the Potomac with Longstreet that Ewell wasn’t going

beyond the Susquehanna, just as he knew McClellan wasn’t crossing the Chickhominy

at any time soon, in June 1862, or that Pope’s army would be crossing Great

Run, where Early’s brigade was situated in August 1862, any time soon.

The Wrightsville Bridge

That neither Ewell nor Early had any chance of getting

possession of the bridge at Harrisburg or Wrightsville, Mr. Mingus debunks

with plain fact: “Shortly before 8:00 p.m. (June 28) Colonel Frick gave the

order. John Denny and his companions threw torches onto the oil soaked floor

and timbers. . . Soon the span was fully engulfed, filling the evening sky

with glowing embers” as “Rebels now crowded the Wrightsville riverbank.”

Shortly the flaming spans collapsed, one by one, into the river. Of course the

certainty that Lee couldn’t be planning to cross the Susquehanna induced Meade

to presume Lee would appear in the direction of Baltimore and he reacted to the

presumption by dispersing his army along the Pipe Creek line, his right flank

extending as far as Manchester. Which, of course, gave General Lee the opportunity

he was looking for, his eyes at all times being on the target of the enemy’s army.

Joe Ryan

|