| Read all the Civil War Sesquicentennial articles | Comments and Questions to the Author |

The War in the West

By June 3, 1862, with a hundred thousand soldiers organized into three army corps, Major-General Henry Halleck, had forced Confederate General Beauregard, with less than fifty thousand men, to abandon the defenses of the railroad crossroad at Corinth and retreat south, down the Mobile & Ohio Railroad to Tupelo, Mississippi. Halleck now had to decide what to do next.

The obvious prime objective for the Union in the West was to capture Vicksburg. No doubt Halleck spend long hours calculating the probabilities of capturing the point; that, at the end of the analysis, he decided against attempting the effort is hardly surprising, given the objective circumstances he was confronted with.

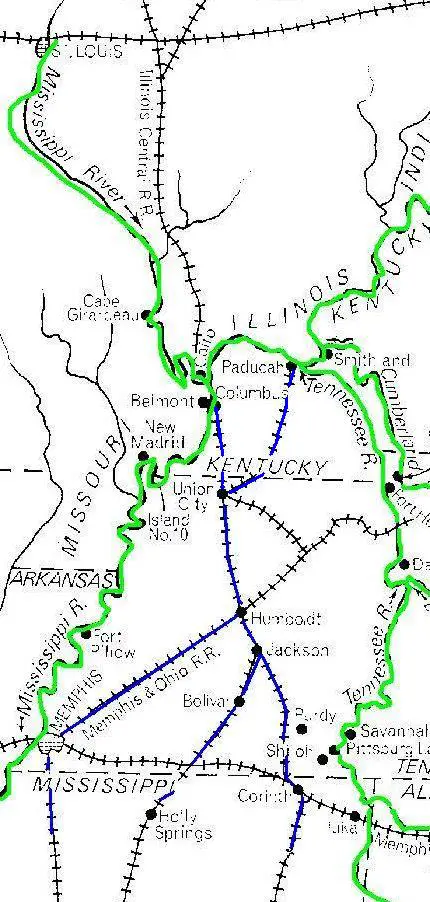

Upper Mississippi 1862

The historians and civil war writers generally turn Halleck into a caricature at this point in his career, claiming quite wrongly that he should have kept his 100,000 soldiers together and marched south into Mississippi with the objective of capturing Vicksburg. As Curt Anders, one of Halleck's biographers has put it, referring to the critics, Halleck, at this point, "was excessively timid, entirely too cautious, a fool easily fooled."

William Sherman, who helped create the myth that VIcksburg was attainable in 1862, writing in 1891, had a different view of Halleck's professional abilities: "General Halleck was a man of great capacity, of large acquirements, and at the time possessed the confidence of the country, and of most of the army. I held him in high estimation, and gave him credit for the combinations which had resulted in placing this magnificent army of a hundred thousand men, well equipped and provided, with a good base, at Corinth, from which he could move in any direction. Had he held his force together, he could have gone to Vicksburg. [But] the army had no sooner settled down at Corinth before it was scattered."

Contrary to Sherman's view that Halleck "could have gone to Vicksburg," the objective evidence is plain that Halleck took a long, cold look at the map and recognized immediately the impossibility of capturing Vicksburg by marching an army of 100,000 men south.

The Actual State of Things

As a consequence of Halleck's capturing Corinth, the Confederates had no choice but to abandon their Mississippi River forts (Fort Pillow) near Memphis and at Columbus, Kentucky. This allowed the U.S. Navy gunboats, stationed at Cairo, Illinois, to steam down the Mississippi to Memphis and attack the Confederate gunboats defending that place. This happened on June 6, 1862, as Halleck was sending John McClernand's division marching along the Memphis & Charleston Railroad toward that place.

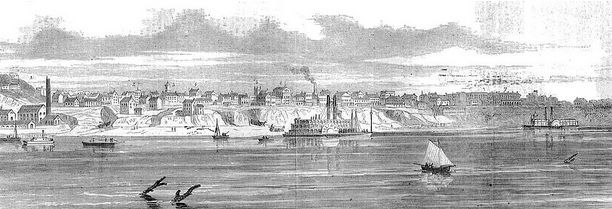

U.S. Gunboats Destroy Rebel Naval Force at Memphis

At this time Memphis was the fifth largest city in the Confederacy, with a population of about fifty thousand citizens occupying a street grid covering about four square miles. The city sits on high bluffs which, in 1862, had deep ravines cut in their face through which roads ran up to the city proper from the river bank. The river bank, itself, was lined with an extensive collection of wharfs that could support the landing of a hundred steam vessels. The cargo unloaded at the wharfs was distributed through the Mississippi and Tennessee Valleys by means of three railroads: The Memphis & Charleston, the Memphis & Ohio, and the Mississippi & Tennessee. Clearly, as long as the civilian population could be held in check, Memphis made the perfect base of operations for a movement southward toward Vicksburg.

Memphis Rail Network in 1862

Memphis in 1862

Assuming the railroads were in operational order, Halleck might have used most advantageously the Mississippi & Tennessee Railroad and, from Grand Junction, Tennessee, the Mississippi Central Railroad, to move daily the huge tonnage of supplies the army would require, south as far as Grenada, Mississippi. Once the Union army reached Grenada, Beauregard's position at Tupelo would now be turned and he would have to retreat further south, probably to Meridian. Building up a depot at Grenada, Halleck could then march his army toward Vicksburg on the ridge between the Yazoo and Big Black Rivers, using the Big Black to protect his left flank. The distance to be marched approached 200 miles, almost twice as many miles as those that McClellan's army covered in its movement from Fort Monroe to Richmond. It had taken McClellan about six weeks to cover about 100 miles in the midst of constant rain storms. Therefore, one can reasonably assume it might have taken Halleck about ten weeks to reach the vicinity of Vicksburg; thus, if he had started the march on June 5 he should have been in front of Vicksburg by about August 5. (With navy gunboat support arriving from both Memphis and New Orleans)

But, in fact, the railroads were not in operational order, were not likely to be in operational order any time soon, and, even if put in operational order, they would quickly be put out of order by Confederate cavalry raids striking the roads at innumerable points. As Sherman tells the story: "On June 7, I reported to Halleck that the amount of work necessary to reestablish the railroad between Corinth and Grand Junction was so great, that he concluded not to attempt to repair it, but to rely on the road back to Jackson, Tennessee, and forward supplies by wagon to Grand Junction; and I was ordered to move to Grand Junction (from south of Corinth) to take up repairs from there toward Memphis. The enemy's detachments could strike the Memphis & Charleston Railroad (as well as the others) at so many points, that no use could be made of it." Compounding the problem of operational order was the additional fact that Halleck did not have available sufficient locomotives and rolling stock to move the supplies, even if the tracks and bridges were intact. All the locomotives and rolling stock attached to the civilian use of the railroads had either been taken south by Beauregard's retreating army, or were shoved into the swamps bordering the tracks.

In Halleck's mind, then, the objective viability of capturing Vicksburg turned on the practical reality that the railroad net—as it existed at the time―could not possibly support the movement of 100,000 men and hundreds of animals almost two hundred miles into the interior of Mississippi.

Locomotive and Cars in 1862

The railroads would have been required to deliver, on a daily basis, over six hundred tons of supplies to the front of the moving mass of men and animals. The logistics of doing this was impossible for Halleck to master with the resources available to him. First, the railroads were single track, meaning loaded trains going south would be delayed by unloaded trains going north; second, the evidence shows that there were almost no locomotives available to Halleck, to pull the ten-car trains; third, and most overwhelming, was the fact that Halleck did not have sufficient cavalry to protect the railroads between the Mississippi border and Grenada, much less between Memphis, Jackson, and Grand Junction, from guerrilla raids. Nor could he protect, for the same reason, the additional two hundred miles of railroad between Grand Junction and Corinth, Tennessee, and Columbus, Kentucky. To support the masses of infantry required to capture Vicksburg by a frontal assault against its east-facing defenses, by means of a 400 mile line of railroad, subject to constant interruption by guerillas operating in the Union rear, was objectively an expectation for a general in Halleck's position too unreasonable to be seriously entertained.

Railroad Net: Tennessee & Kentucky

Realizing this, Henry Halleck did the intelligent thing: he decided to consolidate his hold on the territory―some four hundred square miles—that his operations had so far achieved, and move Buell's army into East Tennessee, with its objective being the capture of Chattanooga. Putting Pope's army in front of Corinth and Grant's army behind him, to guard West Tennessee, Halleck, on June 5, ordered Buell to move his army east on the line of the Memphis & Charleston Railroad to connect up with a Union force, under Michel, that was then occupying Decatur, Tennessee, about thirty miles west of Chattanooga.

Halleck's decision to send Buell east makes a great deal of sense, given the impossibility of moving overland to Vicksburg. By standing on the defensive at the northern border of Mississippi, holding the line of the Memphis & Charleston Railroad between Memphis and Corinth with elements of Grant's Army of Tennessee, Halleck pushed Buell's Army of the Ohio eastward two hundred miles, with the objective of gaining control of Chattanooga, another major railroad crossroads, and with it control of East Tennessee. But, for the same reason he could not get an army to Vicksburg, Halleck could not get Buell to Chattanooga.

Reorganization, Again

For Halleck's subordinate generals, June was a month full of change. On June 19, his army turned over to William Rosecrans, John Pope was ordered to go to Washington. Though supposedly in command of the District of West Tennessee, with Buell in command of the District of East Tennessee, Grant found himself still sidelined by Halleck. Buell once again was on his own, moving east with essentially an independent command.

As for Grant, it was plain to him as well as everyone else, that Halleck did not respect him as a soldier. First, there had been the demeaning remarks Halleck had made in several messages, send to Grant in the first week of March, and Halleck's ordering Grant to remain in the rear at Fort Henry while Charles Smith, a subordinate general in rank to Grant, commanded the expeditionary force that eventually went into camp at Pittsburg Landing. (Whether Halleck intended at that time to dump Grant, he shrugged the thought off quickly enough and put Grant back into the lead command.) Second, after the Battle of Shiloh, apparently his disgust with Grant renewed, Halleck stripped him of field command and sent him to the rear to sit on his hands while George Thomas, another general inferior to him in rank, took field command of his army on the march to Corinth and handled it during the subsequent siege. Now, again restored to command of the Army of Tennessee and placed in command of the West Tennessee District, Grant was still being ignored, with Halleck issuing orders directly to his division commanders. On June 23, with Halleck giving orders directly to Grant's divisions in the field, he left Corinth and rode to Memphis where he established his headquarters. Grant put his situation this way: "My position at Corinth, with a nominal command and yet no command, became so unbearable that I asked permission to remove my headquarters to Memphis."

Clearly, Halleck thought Grant was suited for nothing more than taking care of the rear areas, responsible for funneling troops and supplies forward to the front which was in the charge of officers like Sherman, Thomas and Rosecrans, the latter having stepped into Pope's shoes.

Buell Struggles With Supply Problems

When Halleck brought up with Buell the idea of his moving toward Chattanooga, over two hundred miles away, Buell's reaction was to insist that the movement should be in the direction of Nashville, where his army could get on the Nashville & Decatur Railroad and move by it to McMinnville and then head south toward Chattanooga.

Buell's Preferred Route to Chattanooga

Halleck rejected this idea, insisting that Buell use the Memphis & Charleston Railroad. (This meant Halleck would be moving supplies from Jackson, Tennessee, down to Corinth, and then east.) Buell had good reasons why this would not work. First, the road passed through the driest and barest terrain possible and the temperature would be in the hundreds, meaning that there would be very little clean water available for the men in the creeks and streams feeding the Tennessee River. Second, as with the obstacles to the Vicksburg operation, there were few locomotives available and those were being used to transport working crews and materials to the many bridge sites where repairs were necessary. Whichever railroad was used, Buell would have to detach substantial amounts of men to guard the bridge crossings, and the rails themselves, from guerrilla depredations; but the problem would be worse on the railroad running through north Alabama than on the one running through East Tennessee, so he argued. But Halleck ordered Buell to draw his supplies from Corinth.

The

Nashville & Decatur Railroad joined the Memphis & Charleston Railroad

at Decatur and another branch also connected at Stevenson. Once Buell reached

these points he could make them his depots. In the meantime, some supplies

might reach his line of march by way of the Tennessee River at Eastport and Florence. Supplies could be landed at these points and wagoned six to ten miles to Iuka,

put on cars and hauled to his front as he moved east. (Beyond Florence, the

river in June was too shallow to allow steamboats to pass up it.)

The

Nashville & Decatur Railroad joined the Memphis & Charleston Railroad

at Decatur and another branch also connected at Stevenson. Once Buell reached

these points he could make them his depots. In the meantime, some supplies

might reach his line of march by way of the Tennessee River at Eastport and Florence. Supplies could be landed at these points and wagoned six to ten miles to Iuka,

put on cars and hauled to his front as he moved east. (Beyond Florence, the

river in June was too shallow to allow steamboats to pass up it.)

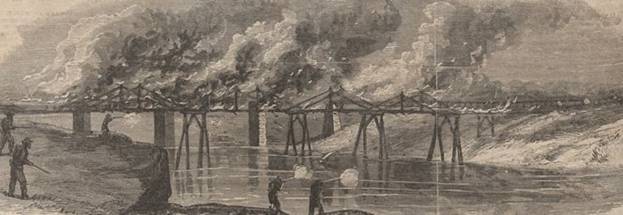

By June 20, Buell had gotten as far east as Florence; a distance of sixty miles. By the end of June his lead division―the rest were strung out behind it—reached Huntsville (a distance of 110 miles) where Michel, with 10,000 men was waiting. He wanted to switch now to the Nashville & Decatur Railroad, but the rebel guerrillas had destroyed the Elk River Bridge. (The only issue for history is, whether he would have gotten to the same spot quicker going the other way)

Elk River Bridge

On June 30, with McClellan in headlong retreat, Stanton asked Halleck for 30,000 men to be sent east. The troops would have to come from Grant's district as Lincoln wanted Buell to continue toward Chattanooga. By this time Buell had gotten the Nashville & Decatur Railroad open, but there were no locomotives, so he had to continue with the struggle of getting supplies moving to him from Corinth, now over 110 miles away, on a railroad constantly being interrupted by rebel raids. And to get to Chattanooga he still had to cross the Tennessee River twice. And so matters rested: Buell dragging eastward; Halleck holding the Mississippi border while rebel cavalry units swarmed his rear

The Confederates Reorganize Too

The Confederate army, under Beauregard's command, reached Tupelo by June 9 without serious difficulty. Bragg, commanding the rear guard, had lost six trains loaded with supplies to Halleck's pursuit, the bridge over the Tuscumbia River being destroyed by his own pickets before the trains could cross it. On June 14, Beauregard, who had been seriously ill for many weeks, left the army command to Bragg and went into Alabama to find a place to rest. On June 20, President Davis ordered Bragg to assume command of the Confederate forces in the West.

Bragg

accepted the command under dire circumstances: the desertion rate was soaring,

there was little good water and very limited supplies. The loss of Corinth had severed direct rail communications with the Eastern seaboard, leaving only the

railroad through Montgomery and Selma, Alabama, to Dalton and Atlanta. But Bragg

got the desertion rate under control, got his men fed, found them water, and

replaced the officers killed at Shiloh. By June 30, the army had recovered its

health, discipline and drill had improved the morale of the soldiers and new recruits

were arriving.

Bragg

accepted the command under dire circumstances: the desertion rate was soaring,

there was little good water and very limited supplies. The loss of Corinth had severed direct rail communications with the Eastern seaboard, leaving only the

railroad through Montgomery and Selma, Alabama, to Dalton and Atlanta. But Bragg

got the desertion rate under control, got his men fed, found them water, and

replaced the officers killed at Shiloh. By June 30, the army had recovered its

health, discipline and drill had improved the morale of the soldiers and new recruits

were arriving.

Leaving

his veteran Tennessee troopers behind, Bedford Forest, the mad rebel cavalier, at

Bragg's instigation, was sent to Chattanooga on June 11. He arrived in Chattanooga on June 18, with some two dozen officers and men from his old regiment, and

took command of a cavalry brigade composed of the Eight Texas and some Georgia and Kentucky companies. Forest was to bring these units together, molding them

into a fighting force that would wreck havoc on Buell's supply lines for the

next two months. Together with John Morgan, Forest began planning an operation

against the Nashville & Decatur Railroad and the Union depot at

McMinnville.

Leaving

his veteran Tennessee troopers behind, Bedford Forest, the mad rebel cavalier, at

Bragg's instigation, was sent to Chattanooga on June 11. He arrived in Chattanooga on June 18, with some two dozen officers and men from his old regiment, and

took command of a cavalry brigade composed of the Eight Texas and some Georgia and Kentucky companies. Forest was to bring these units together, molding them

into a fighting force that would wreck havoc on Buell's supply lines for the

next two months. Together with John Morgan, Forest began planning an operation

against the Nashville & Decatur Railroad and the Union depot at

McMinnville.

Post Script Of course, if we put ourselves in General Lee's shoes, giving him the same circumstances as General Halleck faced, is it unreasonable to expect that Lee would have held Halleck's army together and moved it southward as far as he could, especially with Stonewall with him? At some point well short of Vicksburg he would have stopped, for sure, and nailed down his line of communication with Memphis which stretches back over 200 miles into Tennessee.

Unlike McClellan, who had the great advantage of being dependant on only fifteen miles of railroad, Lee, in Halleck's shoes, would be dependant on no less than two hundred. It just seems impossible that the length of the Mississippi Central, from Grand Junction to Grenada, could have been made secure. (Six months later, when Grant tried to use it, his depot at Holly Springs was immediately overrun and he had to turn around.) And had the effort been made there certainly would have been no endeavor by Buell against Chattanooga and East Tennessee. In the final analysis, the call belonged to the Commander-in-Chief. And, although the players, probably intentionally, have left no record behind that proves the fact, it is hard to believe Lincoln didn't make it. |

Joe Ryan

What Happened in June 1862

In The House of Representatives

The War In The West

The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant June 1862

The War In The East

| Read all the Civil War Sesquicentennial articles | Comments and Questions to the Author |

|

Joe Ryan Original Works @ AmericanCivilWar.com Joe Ryan Video Battlewalks |

|

| About the author: Joe Ryan is a Los Angeles trial lawyer who has traveled the route of the Army of Northern Virginia, from Richmond to Gettysburg, several times. |

||

Battle of Gettysburg

General Robert E. Lee

General JEB Stuart

General Jubal Early

Confederate Commanders

General Joseph Hooker

Union Generals

American Civil War Exhibits

State Battle Maps

Civil War Timeline

Women in the Civil War