The NAACP Pulls Down The Rebel Flag

|

The sesquicentennial of the Civil War has barely begun and the NAACP has already made its policy toward celebration plain: We Americans, white or not, should view the Southern experience of the Civil War as the Jews view the German experience of the Holocaust. In the political view of the NAACP, in other words, the Southern soldier, much less his friends and family, was as base as the German soldier who facilitated the extermination of Jews. And his descendents should bow their heads in shame and hide the location of his grave.

In a historically black neighborhood in South Carolina 20 miles from where the Civil War began, Annie Chambers Caddell has flown a Confederate flag from her porch for years. Dozens of neighbors have protested against it, and one person even threw a rock. Although Caddell initially put up a wooden lattice and fences to shield the flag from view, she has now raised the flagpole higher than the fences so the flag can be seen, the AP reports. Caddell insists the flag is part of her Southern heritage — her ancestors fought for the Confederacy — and says she’s not taking the flag down any time soon.

The policy of the NAACP manifests itself most blatantly in the organization’s persistent attack on the public display of the Confederate battle flag. To the NAACP the display of the battle flag is racist behavior—nothing more or less; and the flag itself a symbol of a racist heritage that through violence sought the breakup of the Union in order to maintain slavery.

In The View Of The NAACP It’s Proper To Fly This

Or This

But Not This

The NAACP’s view of things hangs on the indisputable fact that, in the Fifties and early Sixties, the flag was on occasion waved in public by racist hands.

High School Students waving the flag in Montgomery Alabama

Mississippi Governor Ross Barnett in 1962

But more often than not, the racists of the Sixties waved American flags to make their point, or just let sneers and jeers get their message across.

Little Rock 1956

15 year old Dorothy Counts walking to school in North Carolina

Who over fifty can forget the image of Alabama Governor George Wallace, standing in the door of the Admissions Office of the University of Alabama, giving bodily presence to his slogan of the early Sixties, “Segregation in the past, segregation now, segregation forever” Yet, by 1969, he was on the phone, calling black high school athletes begging them to come play football for the Crimson Tide; and they did! But not, at first, as quarterbacks.

Governor George Wallace Confronting the United States Government

The NAACP must leave out of its complaint the image of the Klu Klux Klan waving the flag as the Klan’s sacred symbol, besides the white robe and hood, is a flaming cross.

So a few racist white kids of the Fifties and early Sixties sometimes waved the battle flag in the faces of African-Americans braving the mob in front of the high schools. Does this fact mean that it is reasonable for the NAACP to insist the flag has no important meaning beyond the racist behavior of the few caught up in the prejudice of the moment?

Hardly: The Confederate battle flag is not, in historical fact, the defining symbol of the South’s intent to maintain slavery, it is the defining symbol of one large population of white people resisting the aggression of another large population of white people—the latter population motivated to restrict black folk to the territory of the Southern states.

The Civil War, at the bottom of it all, was about white people fighting white people because neither side wanted to live as social equals with Africans. Lincoln’s policy—the Republican Party’s policy—was to restrict slavery in order than white people (Irish and German predominantly) could immigrate to the Territories of the United States without fear that Africans would appear on the lot next to theirs. This policy, in its essence, was a pretense for the domination of the South by the North; one would have to be mildly retarded not to grasp the reality. So the Southern states seceded from the Union, a perfectly logical and “legal” step to take under the circumstances of the case, and, among others, the Army of Northern Virginia was raised, with the mission of defending the Confederate Capital, and its soldiers fought the invaders, giving the great battle flag of their de facto country honest and faithful service to the bitter end.

The white guy’s people “died because of this flag?” This would be a great surprise to the soldiers of Lee’s army, who resisted Lincoln’s invasion of their country. The black guy’s people “died because of this flag?” What an absolutely silly idea. The black guy’s people were bystanders, watching from the sidelines as white men plummeted each other to death. Is there properly a self-imposed limitation to the public display of the Confederate soldiers’ great battle flag? Of course there is. In the Sixties, attending Tiger football games at the University of Missouri at Columbia, I was a bit surprised to see giant flags waving from the upper tiers of the Stadium as the Mizzou marching band played Dixie. At that time I had no interest in, or any ideas about, the American Civil War. So I was unable to understand the point. By 1969, the year I graduated, both Dixie and the battle flag had been banned from the games. Unless your team’s name is The Rebels, the flag has no relevance to sports. (And even then perhaps the flag can be misused.)

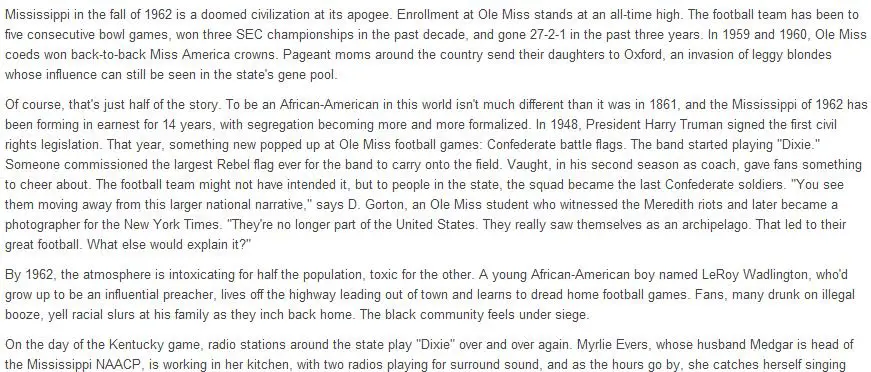

ESPN Black History Month, Ghosts of the Past Written by Wright Thompson

In the heated atmosphere of the Fifties, as finally desegregation of schools became the national rule, the legislatures of several states allowed the display of the flag on their capitol domes. In this context, the symbol of the flag is plain: it signified the State’s resistance to the mandate of the Federal Government. Forty years later, in 1994, the flag was removed from the Alabama Capitol and, in 2002, it was removed from South Carolina’s Capital, although, to the chagrin of the NAACP, it is still displayed on the grounds.

The flag, or elements of it, can be found in the State flags of Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and Florida.

Mississippi’s State Flag

Alabama’s State Flag

Georgia’s State Flag Then

Now

Florida’s State Flag

A State flag should reflect the history of the state, its formation, its growth, even its resistance to tyranny; yet it should not trigger chagrin or true bitterness in any substantial percentage of its people. All reasonable people should be able to agree on this. The resistance of these states to the rule of Lincoln’s government, manifested by our Civil War, was the righteous reaction of a minority to an oppression being inflicted by the majority. The irony is that it resulted, a hundred and fifty years later (a second of time in the history of the human race on earth), in the complete integration of the African race—the ostensible cause of the Civil War—into the social and political fabric of each of these States. It’s time, then, that the symbolism of resistence inherent in the South’s battle flag, be removed from these flags. Leave it to wave in recognition of the heroic courage of the young white men of the South, who braved the horrors of war to protect their states from the Federal Government’s unconstitutional invasion. If this means rock concert-goers (fans of Tom Petty and Kid Rock come to mind) might be exposed to the stars and bars, what harm is done? Perhaps the NAACP will explain.

Of course, there is a great deal really that the N.A.A.C.P. can celebrate about the 150th anniversary of the Civil War that relates directly to the participation of African-Americans in it. After January 1, 1863, over two hundred thousand Africans served as Union soldiers in the war.

PHOTOGRAPHS AND IMAGES OF AFRICAN UNION SOLDIERS

Writing of their conduct during Grant’s Virginia campaign, in 1864, General W.F. Smith, commander of the 18th corps, said: “No nobler effort has been put forth and no greater success achieved than that of the colored troops. With the veterans of the corps they have stormed the works of the enemy and carried them, taking guns and prisoners and displaying all the qualities of good soldiers.” General Ben Butler echoed this view when he wrote, in salutation: “The colored soldiers, by coolness, steadiness, determined courage and dash, have silenced every cavil of the doubters of their soldierly capacity, and have brought their late masters to consider themselves whether to employ them as soldiers.” Twenty-one Africans were awarded the Medal of Honor for conduct above the call of duty. African-Americans Soldiers Awarded the Medal of Honor Bruce Anderson It is a sad commentary on the politics of the NAACP that it fails to recognize the value and importance to the country of the thousands of African-Americans who actively participated as soldiers in the American Civil War. One of the most significant memorial days of the Civil War is Gettysburg Remembrance Day, held on November 19th of each year to commemorate not only the men who fought the battle of Gettysburg but also Abraham Lincoln's visit to Gettysburg National Cemetery where he gave the Gettysburg Address. On this day, thousands of men and women visit Gettysburg and join in a one hour parade, as both participants in the parade and observers of it; many of these visitors spend the day on the streets of Gettysburg, dressed in authentic period garb, recreating a realistic picture of what the people in the town of 1863 looked like.

Predominantly, it is true, the crowd and the parade participants are white, but there are an intrepid few who are black.

It is a sad state of affairs, indeed, that these men are not encouraged by the NAACP, and that the NAACP has no interest in encouraging African-American men to come to Gettysburg for this event in regiment, if not brigade, strength—with all the great banners of their regiments flying in the breeze as they march in their place in the long column of Union soldiers winding its way down King Street, wheeling sharply into Baltimore Street and passing through the town, to the cadence of their snare drums and the bark of their officers. Eight hundred black men in Union uniform as a solid block filling the street in fluid motion; it would be a grand sight conjuring a view of the full strength of the Republic's grand army.

Presentation of Rebel Flags

The House was divided on the motion; and there were—yeas fifty-three, noes not counted Mr. Lovejoy of Illinois: "I demand the yeas and nays. This has been ordered by the War Department; and according to the gentlemen, we have no right to oppose anything done by military men. The War Department has ordered the presentation of these flags." Mr. Dawes of Massachusetts: "I would like to know how these flags are to be presented to us, if we will not receive them. I do not want to magnify those rebel flags in this way, and I hope that Congress will respectfully decline to receive them in this public manner." Mr. Campbell of Pennsylvania: "These are the trophies which have been won by our brave officers and soldiers upon hotly contested battlefields. I would magnify the deeds of our officers and soldiers, and not the flags. These flags represent the blood and struggle of these brave men, and I hope, in that view, they will be received, and treated with respect." [Laughter] Now, sir, if there was a riot in this city, and the municipal authorities had at last succeeded in quelling it, and the proposition should be made that the muncipal council should assemble, and that there should be a public presentation of the banners and transparcencies, or the badges which had been carried through the streets by the rioters, would anybody suppose that such a proposition was in harmony either with self-respect or public decency; and, if not, why should we accept the presentation of a flag—not a piece of bunting simply, but a flag which means more than that, coming from a people who have no flag and who have no existence, national or otherwise; but who are simply rebels. Now, sir, I hope there will be no hesitation in dispensing with a public presentation of these rebel flags, for that is no part of the resolution which we have adopted." Mr. Campbell: "I think the gentleman from New York misunderstood my remarks. I intended to say distinctly that our soldiers who sent these trophies from distant battlefields were to be treated with respect by giving these trophies a proper reception; not, however, that these trophies themselves were entitled to any respect anywhere." Mr. Lovejoy: "The law of the land requires, as I understand it, that all flags taken in battle shall be presented by the officers of the Government, and placed at the disposal of Congress. I do not think we respect the rebels by the action which is proposed. To suppose that by receiving these rebel flags we pay respect to the rebels themselves is the most preposterous idea that could ever enter the human brain. I am willing to receive, as a member of Congress or an individual, every flag taken in battle—the more the better. They are the evidence of the power of this Government to suppress this southern rebellion. I now withdraw my call for the yeas and nays. I want the clerk to read the law on the subject of captured flags." The Clerk read as follows: "That the Secretaries of War and Navy be directed to cause to be collected and transmitted to them, at the seat of the Government of the United States, all such flags, standards, and colors as shall be taken from their enemies; that such flags shall be then transmitted to the President of the United States, for the purpose of being, under his direction, preserved and displayed in such public place as he shall deem proper." Mr. Crittenden: "What is the date of that law?" The Clerk: " The 18th of April, 1814." Mr. Edwards of New Hamsphire: "The House has decided that this presentation should take place." [Cries of "No!" "No!"] Mr. Roscoe Conkling: "It is no part of the resolution of either House." Mr. Edwards: "It is now to be determined what is the will of the House in this matter. As an individual, I am in favor of the reception of these flags taken from armed rebels by our brave officers and soldiers. Now, sir, I say, if any gentleman wishes to draw any analogy between a riot in this city and half a nation in arms, he argues from premises which have no influence with me. Sir, we have witnessed within the last three weeks the most desperate exhibition of courage and military skill that has ever been mainifested in any part of the world. To our Navy on the coast and to the soldiers of the West we are indebted for that which has changed the gloom into cheerfulness. These flags have been wrested from an enemy by our sailors and soldiers; and as a tribute of admiration, I would now—[disturbance I the galleries] The Speaker: The Chair appeals to the gentlemen in the galleries to preserve order." Mr. Richardson of Illinois: "I think the galleries have behaved better than we have." [laughter]

Mr. Sedgwick of New York demanded the yeas and nays. Mr. Lovejoy: "Has the Secretary of War arranged for the presentation of these flags? [Cries of "Call the roll!" "Call the roll!"] The question was then put; and it was decided in the affirmative—yeas 69. nays 62. So the resolution was agreed to. Note: Most of the over 400 captured rebel battle flags were entrusted to the Museum of the Confederacy, in Richmond, VA, by mandate of the United States Congress and the Commonwealth of Virginia in 1905.

Joe Ryan

Books Available to Read

John M. Coski, The Confederate Battle Flag: America’s Most Embattled Emblem, Harvard University Press (2005)

G. Schedler, Racist Symbols and Reparations: Reflections on Vestiges of the American Civil War, Rowman & Littlefield (1998)

J. I. Leib, Flag, Nation, and Symbolism in Europe and America, Routledge London (2007)

J.M. Martinez, Confederate Symbols in the Contemporary South, University of Florida Press (2000) |

| Email Comments and Questions to the Author |

|

Joe Ryan Original Works @ AmericanCivilWar.com Civil War Video Battlewalks |

|

| About the author: Joe Ryan is a Los Angeles trial lawyer who has traveled the route of the Army of Northern Virginia, from Richmond to Gettysburg, several times. |

||

Battle of Gettysburg

General Robert E. Lee

General JEB Stuart

General Jubal Early

Confederate Commanders

General Joseph Hooker

Union Generals

American Civil War Exhibits

State Battle Maps

Civil War Timeline

Women in the Civil War