| Read all the Civil War Sesquicentennial articles | Comments and Questions to the Author |

PART I

The Object and Cause of the American Civil War

Congress to Confiscate Rebel Slaves

Editor's Note: State departments of education and, consequently, text book writers, have constructed a false impression over the last one hundred years, of what exactly caused the American Civil War. Invoking a chain of abstractions, they present the cause of the war as a series of economic and political events that induced the North and the South to engage in violent conflict. Resentments over governmental policies of tariffs, taxes, and immigration into the territories, coupled with the splintering of the Democratic Party into factions, they teach, essentially constitute the sum of the complex causes of the Civil War. Yet, the evidence they ignore shows indisputedly that the real cause of the Civil War was simply white racism, a deep virulent prejudice by all but a very few of the white people that inhabited the States both north and south of the Mason-Dixon Line, in 1861.

Nowhere in the textbooks these educators provide, can the intelligent high school or college student find the objective truth of history. As a consequence americancivilwar.com offers those students interested in understanding what was really at the bottom of the war this abridged version, transcribed verbatim in all essential parts, of the Congressional Record of the Second Session of the Thirty-Seventh Congress of the United States, as printed by the court reporter, John Rives, in 1862.

In The United States Senate

Confiscation of Rebel Property

March 4, 1862

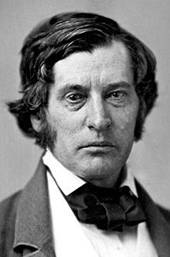

The Vice President: Senate Bill No. 151, to confiscate the property and free the slaves of rebels is now before the Senate; and upon that question the Senator from Pennsylvania, Mr. Cowan, is entitled to the floor.

Mr. Cowan of Pennsylvania: We are standing now squarely face to face with questions of most pregnant significance. Shall we stand or fall by the Constitution, or shall we leave it and adventure ourselves upon the wide sea of revolution? Shall we attempt to liberate the slaves of the people of the rebellious states, or shall we leave them to regulate their domestic institutions the same as before the rebellion?

If we can suppose consummated the scheme the bill proposes, we shall

have the following result: This bill proposes, at a single stroke, to strip

four millions of white people of all their property, real and personal, and

mixed, of every kind whatsoever, and reduce them at once to absolute poverty;

and that, too, at a time when we are at war with them, when they have arms in

their hands, with four hundred thousand of them in the field opposing us

desperately.

If we can suppose consummated the scheme the bill proposes, we shall

have the following result: This bill proposes, at a single stroke, to strip

four millions of white people of all their property, real and personal, and

mixed, of every kind whatsoever, and reduce them at once to absolute poverty;

and that, too, at a time when we are at war with them, when they have arms in

their hands, with four hundred thousand of them in the field opposing us

desperately.

Now, Sir, it does seem to me that if there was anything in the world calculated to make that four millions of people and their four hundred thousand soldiers in the field now and forever hostile to us and our Government, it would be the promulgation of a law such as this.

I do not know the value of the property forfeited by this bill; except to say it is enormous—to be computed in billions. But, Sir, the bill goes farther and forfeits a vast amount of property which, when forfeited, cannot be confiscated. I mean their property in negro slaves.

Now, I do not mean to stop here to discuss their right to this species of property. What I mean to say is, that this bill would liberate, perhaps, three millions of slaves; surely the most stupendous stroke for universal emancipation ever before attempted in the world.

Those who favor this bill seem determined to impose yet a greater project, of procuring a home for these emancipated millions in some tropical country, and of transporting, colonizing, and settling them there. Surely, sir, we must have been recently transported away from the sober domain of practical fact, and set down in the regions of eastern fiction, if we can for a moment entertain this proposition seriously.

At a time when every energy of the country is put in requisition to suppress the rebellion, when we are in debt equal to our resources or payment, is it not strange that this scheme, which would involve us in a cost more heavy than even the present war, should be so coolly presented for our consideration, and urged to its final consummation with a kind of surprise that anyone should oppose it?

The bill is in direct conflict with the Constitution of the United States, requiring us to set aside and ignore that instrument in all its most fundamental provisions; those which guarantee the life, liberty, and property of the citizen, and those which define the boundaries between the powers delegated to the several departments of the Government.

Pass this bill, sir, and all that is left of the Constitution is not worth much. Certainly it is not worth a terrible and destructive war, such as we now wage for it. And it must be remembered that this war is waged solely for the Constitution, and for the ends, aims, and purposes sanctioned by it, and for no others.

I am aware, however, that some think the Constitution is a restraint upon the free action of the nation in the conduct of war, which they suppose could be carried on a great deal better without it.

We have here in these Halls of Congress solemnly declared that the war was for no such purpose as conquest and subjugation; but that it was for the purpose of compelling obedience to the Constitution and the law. The Constitution and the laws being restored and obedience tendered, is this law one of them? Thousands of these people have been duped into rebellion by being told that we of the North were all abolitionists, intent, when we had the power, to wield it for the emancipation of their slaves, and the destruction of their social system. That slander, sir, was the moving cause of the war.

But when the rebel leaders attempted to provoke a struggle as to whether the common Territories of the nation should be the homes of free white men or of servile negroes, the people of the North resisted it. It was a simple question between the white men and the negroes—which should have the Territories; if the negroes succeeded, the white man would not inhabit them in his company, and if the white succeeded, the negro should not.

The victory was won by the white man; and the creed and doctrine which animated him in achieving it is `Republicanism.' Nothing more, nothing less. So it declared and published everywhere; so it is understood by the people; so it was put forth almost unanimously by the present Congress. We have said we had no right, and we claimed none, to meddle with slaves or slavery in the slave States. All which has been and is now perfectly understood by all not willfully blind.

Then, sir, I say again, that as a Republican, standing upon the Constitution as construed by that party, I protest against this bill as being a total and entire departure from the principles of that instrument. . . I know that many people suppose that our powers under the Constitution have been indefinitely enlarged by the fact that a civil war is now raging, calling into play what is called the `war power' of Congress, by virtue of which we can pass any law we choose which tends or is supposed to tend toward the suppression of the rebellion, and that under it this Bill is warranted by the Constitution.

I think all this will be found a delusion and a snare. Our power today is no greater than it ever was. Nobody pretends that if Jefferson Davis alone had been guilty of treason last year or the year before, and had escaped the jurisdiction of the courts, that Congress could have attained him as a traitor, or forfeited his property, or emancipated his slaves. Even the simplest man would have known that in such case he must be tried, convicted, and punished by law. Nor can the case be altered if one hundred thousand other traitors were in the same category. The grants of power to us in the Constitution were fixed in it from the beginning, and we stand just where we did always.

But the case has arisen where the laws are inadequate to the preservation of the order of society, and the question is, what remedy? Since the laws are silent, the courts destroyed, and the will of the nation discarded, how does the Constitution meet the emergency? Does it meet it, and effectively? I say it does; since the law is of no avail it resorts to force, military force, in other words, war, and those who resist are treated as enemies.

Then, who shall make this war and determine how it shall be carried on? Shall it be Congress, the President, or the judges? Some think the power is in Congress, Some think the President. The Constitution declares that the President shall be the Commander-in-Chief, or, in other words, the force of the nation is put into his hands, investing him with the war-making power, and he must wield it until all resistance has ceased or till peace is made. He is dependant upon the Congress only so far as he needs it to foot his bills and authorize his levies.

In this case the President has the right to take, by way of capture, all the public property of the rebels used in the war, such as forts, ships, ammunition, stores of every kind, but he could not do as this bill proposes to do; he could not follow the rebel after his surrender and take from his house the private property which he had left there for his wife and children, while he was at war. And all this because a Christian civilization has taught the nations that such mode of making war is mischievous and injurious. The modern rule of the law of nations is plainly understood by all: `Private property on land is exempt from confiscation, with the exception when taken from enemies in the field or besieged towns, and of military contributions levied upon the inhabitants of hostile territory.

I am well aware, sir, that there are many who think emancipating the slaves of the rebels ought to be done, because they think slavery is the only cause of the rebellion. In considering this, it is well to remember that there are many evils in the world. Four millions of negros are now in bondage. Where are the signs of their emancipation? Have not hundreds of thousands of these had ample opportunity to throw off their chains within the last few months? Have they done so? And if they have not done so, can you compel them to exchange voluntary servitude for involuntary freedom? I thought the world was old enough for everyone to know, if you want freedom, you must strike the blow which is to secure it.

March 6, 1862

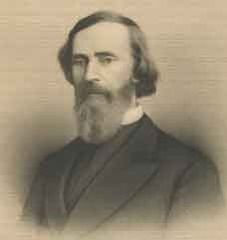

Mr. Morrill of Maine: The great measure before us has

been characterized in this debate in earnest, eloquent, indignant, satirical

speech, as extraordinary, unconstitutional, oppressive, and inexpedient. The

bill contemplates the exercise of the extreme legislative power of the nation

for the purpose of self-preservation and for the overthrow of its domestic

enemies. The primary object of the bill is the suppression of the rebellion. It

proceeds upon the assumption that the insurrection is incited by a faction in

the slave States, holders of the vast proportion of the property and slaves in

those States; that this property and these slaves constitute the incentive and

form the material base of the rebellion; and that, therefore, it becomes the

right and duty of the nation, from the height of its extreme authority, to

award the penalty of condemnation of estate and forfeiture of control over persons

to those who thus conspire against the Government and make war on its

authority.

Mr. Morrill of Maine: The great measure before us has

been characterized in this debate in earnest, eloquent, indignant, satirical

speech, as extraordinary, unconstitutional, oppressive, and inexpedient. The

bill contemplates the exercise of the extreme legislative power of the nation

for the purpose of self-preservation and for the overthrow of its domestic

enemies. The primary object of the bill is the suppression of the rebellion. It

proceeds upon the assumption that the insurrection is incited by a faction in

the slave States, holders of the vast proportion of the property and slaves in

those States; that this property and these slaves constitute the incentive and

form the material base of the rebellion; and that, therefore, it becomes the

right and duty of the nation, from the height of its extreme authority, to

award the penalty of condemnation of estate and forfeiture of control over persons

to those who thus conspire against the Government and make war on its

authority.

But, sir, at the threshold of this measure, we are met with a flat denial of adequate constitutional authority. The nation is involved in the perils of civil war, demanding the instant and decisive exercise of its upmost powers, and yet it is painfully obvious that there exists the most embarrassing contrariety of opinions as to the constitutional powers of Congress, and the policy demanded by the public emergency.

Constitutionally speaking is the nation in a state of war; and if so, what are its powers, under the Constitution, and to what extend to the public perils render the exercise of those powers necessary and expedient?

First, is the nation, for purposes offensive and defensive, for all questions of its authority, to be regarded as in a state of war? The Government has made no formal declaration of war, and the conflict is between the established Government and members of the same Government. Yet it will not be questioned that a state of war may exist between the Government and a portion of the people, and that no formal declaration is necessary to legalize hostilities. As to the policy of war all now happily agree.

The nation, sir, is in a state of war, involuntary war on its part, insurrectionary, causeless, rebellious war on the part of its domestic enemies. As, sir, it matters not that it is not purely public war, conflict between two nations; civil conflict is unqualifiedly war, and has its laws as well defined as conflict between two nations.

Our condition, sir, being that of civil war, I think it must be manifest that the nation possesses all the rights and powers necessary for self-preservation and for dealing with its enemies that are common to a nation in that situation. Clearly the Constitution contemplates the contingency when the Government may be required to draw the sword against internal enemies, and wisely provides for such an event by the institution of an army and navy; and in such contingency imposes no limitation on its power, but plainly designed that it should be left wholly unrestricted, to exercise all the powers and rights of a nation forced to take up arms for its defense.

While, under the Constitution, a state of peace is the normal condition of the nation, a state of insurrectionary war is contemplated, and in such event, the power of the Government over all its enemies is unlimited and unrestrained, and is controlled only by the law of nations. The nation may then deal with its enemies in any way its exigencies may require, not repugnant to the principles of international law.

In its civil functions the Constitution provides for Government with limited power and duties, general in their character. Its war power is of the most absolute character; the right of making war is expressly given to the Federal Government, and the States are expressly forbidden to exercise it. And, sir, the war power is not incidental, but a substantive power, and is that extreme power known to nations as the ultima ratio at the declaration of which civil privileges are in abeyance and municipal laws silent.

I am aware, sir, that there are those who do not agree to this assumed power of the Government; in the words of the late president (Mr. Buchanan), `the Federal Government has no authority to decide what shall be the relations between the Federal Government and the States; that Congress possesses no authority, by force of arms, to compel a State to remain in the Union; that while Congress possesses many powers of preserving the Union by conciliation, the sword was not placed in their hands to preserve it by force.'

There is, sir, some fatal delusion misleading the minds of those who thus reason and act. The history of the origin of the Constitution shows that its founders designed to provide for a government with the essential attributes of government for `domestic tranquility.'

Assuming, then, we are in a state of war, the question is, in what department of government does this power of self defense reside. This is not an open question. The supreme power of making and conducting war is expressly placed in Congress by the Constitution. The "whole power of war," says the Supreme Court, is vested in Congress. Surely we can all agree there is no such power in the judiciary, and the Executive is simply `Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Navy;' all other powers and duties, not necessarily implied in the command of the military and naval forces, are expressly given to Congress. Congress declares war, grants letters of marque, makes rules for captures on land and water, raises and supports armies, provides for and maintains a navy, makes rules for the government of the armed forces, provides for organizing the militia, and is thus invested, in the language of the Supreme Court, `with the whole powers of war.' (Brown v. U.S. 1 Cranch)

There is, then, sir, no limit on the power of Congress; but it is invested with the absolute powers of war—the civil functions of government are, for the time being, in abeyance when in conflict, and all State and national authority subordinated to the extreme authority of Congress, as the supreme power in the peril of internal hostilities. The ordinary provisions of the Constitution, peculiar to a state of peace, and all laws must yield to the force of martial law, as resolved by Congress.

Now, sir, upon principles of international law, what are some of the rights of nations in a state of hostility? In war, says Grotius, "We have the right to deprive the enemy of his possessions, of anything which may augment his strength and enable him to make war.' In the language of Professor Martin, `The conqueror has a right to seize on the property of the enemy, whether moveable or immoveable.' Says the Supreme Court: `War gives the full right to take the persons and confiscate the property of the enemy wherever found.'

Thus, sir, we see that Congress is invested with the whole power of war, and that confiscation of the enemy's property is one of its powers. Confiscation, sir, is the fate of the property of the belligerent—the penalty of war—and there can be no fair pretense that these principles do not apply in the case of a domestic enemy. Confiscation of the estate of the domestic enemy of the nation is the current judgment of the civilized world.

And, sir, necessarily connected with the question of the confiscation of the property of rebels, is that affecting his right to control his slave. If it be allowable to take his property, why not his slave, and which is, indeed, in this case the casus belli? Sir, the well-defined notions of mankind in relation to persons and property, in peace or war, seems wholly to fail to guide us when the shadow of the sable African falls upon us. He is the riddle we cannot tell; the nondescript we constantly fail to comprehend; the visible outline of man with the invisible quality of property, mysteriously united, that confounds us; the grim idol of an idolatry that shocks while it enchants and infatuates. Plainly, that judgment which condemns the person and property of the rebel, necessarily absolves the allegiance of his slave.

The senator from West Virginia, Mr. Blair, supposes slave property to possess a constitutional immunity. He seems to regard the institution as possessing a sanctity akin to that which attaches to the Constitution—its existence essentially the bond of union between the States, and which was carefully protected by the framers of the Constitution. That a war for the liberation of the slaves would be a war for the overthrow of the Constitution. Now, sir, the plain import of this is that the institution is indissolubly bound up with the Constitution and so an element of the essential life of the nation. That the institution and the Constitution must stand or fall together.

Sir, I do not care at this time, to attempt the refutation of these ideas, nor do I stop to take issue with the Senator whether slavery is the real or the predisposing cause of the rebellion. Sufficient that it is the ostensible cause. The Government has inaugurated no war on slavery; but, sir, it has raised the great battle ax of war on rebellion; and on whatever is inseparably connected with rebellion—its guilty cause and support. The right of slavery to exemption from interference is lost in its audacious revolt and armed assault on the Government.

March 10, 1862

Mr. Browning of Illinois: We will have prosecuted the war to a melancholy end if its result shall be only to restore the authority over the revolted States, and overthrow the Constitution. Unless we can save the Constitution with the Union we had better let them both go.

I concede that the bill exceeds in the importance of the principles

which it involves. Its constitutionality is questioned. The power to pass bills

of attainder is expressly prohibited to Congress by the Constitution, and I

believe it is not denied that this is a bill of attainder. How, then, can we

constitutionally pass it?

I concede that the bill exceeds in the importance of the principles

which it involves. Its constitutionality is questioned. The power to pass bills

of attainder is expressly prohibited to Congress by the Constitution, and I

believe it is not denied that this is a bill of attainder. How, then, can we

constitutionally pass it?

I understand the Senator from Maine to derive the power not from the Constitution, but from the existing state of war. Or, to state the proposition in his own language, `the ordinary powers of Government, under the Constitution, are applicable to the nation in a state of peace; and yet, as clearly, the Constitution contemplates the exercise of powers peculiar to a state of war.' The truth of this proposition, I am willing to concede, but I controvert the deductions which the Senator has thought proper to make from it.

The powers of the Government are unquestionably enlarged by a state of war; that is, the Government may constitutionally exercise powers in a state of war which it cannot in a state of peace; powers which are in entire harmony with the Constitution, but which lie dormant during peace, and are brought into exercise and constitutionally asserted only in a state of war.

But is Congress the Government? Do these extraordinary powers belong to Congress; and may Congress exercise them at all either in peace or war? I think not. All the powers which Congress possesses are those which are granted by the Constitution, and they are the same yesterday and today and forever. They do not change, expand, and contract with the uncertain and fluctuating tide of human affairs. The infirmity of the Senator's contrary argument is to be found in the distribution of the powers of Government, a distribution, in my judgment, directly in the teeth of the Constitution.

Says the honorable Senator: `There is no limit on the power of Congress; but it is invested with the absolute power of war. The civil functions of Government are, for the time being, in abeyance when in conflict, and all State and national authority subordinated to the extreme authority of Congress, as the supreme power in the peril of external and internal hostilities.'

There, sir, is as broad and deep a foundation for absolute despotism as was ever laid. In a time of war, and especially in a time of domestic war, when the restraints and protection of the Constitution are more than at any other time needed to check and control inflamed passions, and protect minorities from the oppression and tyranny of excited majorities, life, liberty, property, all are to be held at the will and caprice of Congress, without limitation, or restraint of any kind or character upon its power.

If these extreme war powers be prostituted to the purposes of tyranny and oppression by the President, to whom the Constitution has entrusted them, when peace returns he is answerable to the civil power for that abuse.

If Congress usurps and prostitutes them, the liberty of the citizen is overthrown, and he is hopelessly without remedy for his grievances. The Constitution was not constructed upon a sliding scale; and I know of no single act which Congress may constitutionally do in a time of war that it may not, in equal accord with the Constitution, do in time of peace.

The extraordinary powers which the Government may exercise in time of war, but the assertion of which is denied to it in times of peace, are war powers, vested in and to be wielded by that part of the visible organism which represents the sovereignty of the Government in the actual and potential conduct and prosecution of the war—and that is not Congress. Congress can no more command the Army, or interfere with the command of it when in the field, than it can adjudicate a case at law or control the decision of the court.

The war powers belong to another department of Government. The Congress can exercise no war powers. This question has been considered and I think fully passed upon the Supreme Court, in Luther v. Borden. The Supreme Court there said: `The elevated office of President, chosen as he is by the people, and the high responsibility he could not fail to feel when acting in a case of so much moment, appear to furnish as strong safeguards against a willful abuse of power as human prudence and foresight could well provide. At all events, it is conferred upon him by the Constitution and must therefore be respected and enforced by the judicial tribunals.'

But, sir, if Congress should assume the exercise of the war powers, should usurp them, and should use them for the purpose of tyranny, there is absolutely no remedy to be found anywhere.

I read these cases for the purpose of showing that the war-executing powers are vested in the President and Congress has no more right to touch them than it has to usurp the judicial function of the Government.

This bill is not restricted to property which, by its character or uses, is adapted to aid the rebellion, but strikes at all the property of every kind and character of all the citizens of the seceded States. It sweeps away everything, even the most ordinary comforts and necessities of domestic life, and reduces all to absolute poverty and nakedness. It leaves them the ownership of nothing, and when executed will leave them the possession and enjoyment of nothing. If the bill is constitutional, the instant it passes millions of people in the private walks of life will be stripped of the ownership of everything. They may repent of their past rebellion and return to their allegiance the next day or the next month, but they return bankrupts and beggars, with nothing on earth to make government desirable.

If we recognize the existing state of things as war, then we must also recognize the rebels are public enemies, and deal with them according to the rules of war established by the law of nations. We must deal with them precisely as we would deal with a foreign nation with which we were at war. And if at war with a foreign nation, the law of nations would forbid us to pass a law to confiscate the property of the private citizens of that nation, or even plunder them when our victorious army had invaded their country. Our Constitution, I concede, would not restrain us. We would be restrained by the law of nations.

If we do not recognize the rebellion as war and the rebels as public enemies, but as insurgent citizens only, and deal with them and treat them as citizens, then we cannot pass the law proposed, because the Constitution forbids the enactment of bills of attainder, and this is, in the meaning of the Constitution, a bill of attainder.

Thus, Mr. President, whether we regard the rebels as public enemies with whom we are at war, or only as insurgent citizens, we are, in either case, without power to pass this bill.

I now proceed to submit some views upon the subject which has caused the war. I believe, sir, that slavery is the sole, original cause of the war; that is, I believe, without slavery there would have been no war. And I believe it is slavery alone that maintains the war. A large majority of the people believe as I do, and are anxious that the war shall be made the occasion of wiping slavery out. Suggestions are made that it is the duty of the President to proclaim universal emancipation to the slaves and many people believe he has the power to do so. Your table is crowded with petitions calling on Congress, under the war power, to pass laws for the emancipation of all slaves and I suppose this bill is intended as the first step.

I confess, sir, that I do not comprehend this. All the power of legislation that Congress possesses is derived from the Constitution and the power of emancipating slaves is not included.

To ask the President to proclaim emancipation to the slaves, is to ask him to usurp a power which, in the existing state of things, he does not possess. To ask Congress to do it, is to assume that Congress may disregard all constitutional guarantees, and transcend all constitutional limitations. A state of war does not justify the civil power in abrogating constitutions, nor in violating the rights of person or property. The right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness is as inalienable in the citizen in time of war as in time of peace.

I pass by all refinements as to the name that shall be used to designate the existing state of things. Call it treasonable insurrection, call it rebellion, it is nevertheless war—real, actual, present war. The so-called Confederate states are public enemies. They are at war with the United States and all the laws of war apply.

What are these laws and the enemies' rights? The rebel States by making war upon the United States have, for the time being, dissolved the state of society which previously existed between them; and they can no longer invoke the protection of the Constitution. The state of war permits us to use every method of recognized warfare to subdue them. By the laws of war, we have the belligerent right to seize all the property of those who are in arms against the Government. The Government has the right to seize and confiscate all the property, of every character, including slaves, of those in armed rebellion against this Government, so far as such property may come within reach of our army, and so far as its seizure may tend to cripple the enemy. To accomplish this, neither legislation or adjudication is necessary. The power is a war power, the right a belligerent right.

No officer should be permitted to return slaves to their masters; but they should be received, and used in whatever they could be made most available and efficient in the prosecution of the war; and if any come that cannot be useful, let them pass through the lines and shift for themselves. The Army is not bound to take care of them, and cannot have them as camp followers, to be provided for at the expense of the Government. Let them do the drudgery and labor which would otherwise devolve on our soldiers. Let them open roads, build bridges, dig ditches, erect fortifications, and do labor of every kind which may be needed by our army; and if need be to save the Government from overthrow, the country from ruin, and our homes from desolation. Let them be formed into regiments and companies, and drilled and disciplined and armed, to take their chances for wounds and death in the front of battle.

I would not do this now, because it is not required by the stress of war, and because the measure will be distasteful, if not offensive, to our friends in the slave States. Their situation is peculiar, delicate and embarrassing; and I appreciate the difficulties that surround them.

Two governments cannot exist where before there was but one. Whenever the Confederate States shall be recognized as one of the family of nations, the struggle with us becomes a struggle for our own throats. Our only alternative will be to subjugate or be subjugated, to exterminate, or be exterminated. The responsibility for this state of things is not with us. Then is the time to bring on the negroes. We will then be fighting for our individual lives and the lives of our wives and children; and it would be wicked to refuse to arm fugitives, but to drive them back to be armed against us. And why should we hesitate? Can any one give a reason why, when the necessity arises, we should hesitate?

I know, Mr. President, there are those whose sensibilities are shocked at the idea of the Government accepting the armed assistance of the colored race. They are willing that traitors shall slay our soldiers with every weapon. That is all right; but we must fight them with kid gloves and if even by accident we knock a traitor down, we must wait till he gets up and call to time before we strike again. I am tired, sir, of this war on one side. I am tired of using our soldiers for the base purpose of holding negroes for rebels. If it is war, let it be war in earnest. Let it be quick, fierce, and terrible.

If, on the contrary, we are fighting only to protect the institution of human slavery, if we are fighting only to rivet the fetters more firmly, if the preservation of slavery, and not the preservation of the Government, is the great end and object of the war, then let us disband our armies, break our swords, abase our souls, and cease this wicked and unholy strife.

March 11, 1862

Mr. Carlile of "Virginia:" The bill is entitled `A Bill to confiscate the property and free the slaves of rebels.' Such a sweeping proposition, one better calculated to continue the war forever and exhaust the whole country, never has been in the history of the world.

The ablest speech made this session in favor of converting the struggle into an antislavery war, was made by Senator Conway of Kansas. Let him speak: `The wish of the masses of our people is to conquer the seceded States and hold them as subject provinces.' To accomplish his purpose, he would recognize the so-called Confederate States as a separate nation, and wage war upon them because he believes that the law of war would enable him to deprive the citizens of those States of $2 billion worth of slave property.

They on the other side are pulling the same string at different ends. They want the Confederate Government recognized, they want the rebellion dignified with the name of war.

The bill makes it the duty of the President to colonize the negroes at the cost of the Government. Of course the Government gets its money by taxing the people. The people are to be taxed for lying down, getting up, standing or walking, asleep or awake, all for the glorious privilege of evincing to the work that enlarged philanthropy that can view with complacency the sufferings and groans of the white race, but is horrified at the sight of four millions of negroes comfortable, contended, and unconscious of suffering until informed by some Greeley.

The bill fails to make provision for the negroes who shall be

unwilling to leave the land of their birth and the home of their nativity. That

this latter class will comprise at least 99% of the slaves, is a fact known to all acquainted with the race

The bill fails to make provision for the negroes who shall be

unwilling to leave the land of their birth and the home of their nativity. That

this latter class will comprise at least 99% of the slaves, is a fact known to all acquainted with the race

The advocates of this bill have a scheme, it is clear, to Africanize American society in the southern States. If this is their purpose, I assure them they are mistaken. Self-preservation would compel the States within which slavery now exists, if the slaves were emancipated, either to expel them from the State or reenslave them. If expelled where would they go? The non-slaveholding States, many of them, exclude negroes by express constitutional provisions; others would do so, for we are told by the advocates of emancipation that the negro is not to be permitted, when liberated, to come into their States. What follows? Extermination or reenslavement.

Can it be possible that the Christian sentiment of the North, which it is said demands the abolition of slavery, desires the extermination of the negro race? Such, I trust, is not the sentiment of any considerable number of people anywhere. The result would be that the States would do what they have the acknowledged constitutional right to do, reenslave them. The well being, if not the existence, of the white race would demand their reenslavement, and it would be done. I ask, then, what good to either race would be accomplished by the passage of this bill?

It should never be forgotten that the struggle in which we are engaged is on our part, constitutionally speaking, not a war. We are not engaged in war. Congress makes war, declares war. Congress has made no such declaration, nor has Congress declared that war exists. When we speak of war we generally mean public war. The war spoken of by the writers on the laws of war is public war, that which takes place between nations and sovereigns, where one nation seeks to enforce its alleged rights against another and separate nation. The struggle we are engaged in is, on our part, an effort to suppress insurrection.

Sir, I deny this is a civil war. I pronounce it a rebellion and those engaged in it, rebels. I deny, therefore, that the laws of war would authorize or justify the enactment of this bill. Congress has the power to legislate for the suppression of insurrection, but the insurrection must be suppressed and the rebellion put down by constitutional means, otherwise all that would be necessary to overthrow the Constitution would be to incite insurrection. If Congress were to suppress the rebellion with unconstitutional means there would be nothing for the loyal citizen to fight for.

Mr. President, the Senator from Maine argues that we are engaged in a war, and contends that Congress has the power to do what he says the law of nations authorizes nations to do. Therefore, he argues, we have the power to confiscate the property of the rebels. He would concede to the rebels what they claim, that they are not engaged in rebellion, but in waging war against a foreign government. We are not at war, Mr. President, with a belligerent Power but with rebellious citizens.

There are those who say if there had been no slavery there would have been no rebellion. As well they might attribute the rebellion to the Union, for, if there had been no Union there would be no rebellion against it.

Think you, Mr. President, if General Halleck had announced to the people of Tennessee that his purpose was to confiscate their property and turn them houseless and homeless upon the world, and to free their slaves, Nashville and Clarksville would have been ours? Would they not have been reduced to ashes, and would not their people have rushed to the field and arrayed themselves under the banner of rebellion? Pass this bill and interminable never-ending war will be the result.

Slavery in the District of Columbia

March 12, 1862

Mr. Morrill of Maine: I move to take up for consideration the bill (S.No. 108) for the release of certain persons held to service or labor in the District of Columbia.

The motion was agreed to; and the Senate, as a Committee of the Whole, proceeded to consider the bill.

Mr. Davis of Kentucky: I offer by way of amendment to

this bill, this clause, `That all persons liberated under this act shall

be colonized out of the limits of the United States and the sum of $100,000

from the Treasury will be used for this purpose.

Mr. Davis of Kentucky: I offer by way of amendment to

this bill, this clause, `That all persons liberated under this act shall

be colonized out of the limits of the United States and the sum of $100,000

from the Treasury will be used for this purpose.

I ask for the yeas and nays.

The yeas and nays were ordered.

Mr. Doolittle of Wisconsin: I understand that the effect of this amendment to be to colonize them whether they are willing to be colonized or not. If the amendment was to make colonization voluntary I would vote for it; as it is I cannot.

Mr. Davis: I think I am better acquainted with negro nature than the honorable Senator from Wisconsin. He will never find one slave in a hundred that will consent to be colonized., when liberated. The liberation of the slaves in this District, or in any State, will be just equivalent to settling them in the country where they live; and whenever the policy is inaugurated, it will inevitably and immediately introduce a war of extermination between the two races.

Here there are a great many vagabond negroes in a state of slavery in this city. They are now idle and comparatively worthless; and whenever they are liberated they become greatly more so. A negro's idea of freedom is freedom from work. After they are liberated they become lazy, indolent, thievish vagabonds, Men may hug their delusions, but these are facts heretofore, and they will remain facts in the future. I know this just as well as I know that these gentlemen around me belong to the Caucasian race.

The negroes that are now liberated, and that remain in the city, will become a sore and a burden and a charge upon the white population. They will be criminals; they will become paupers, and the power that would liberate them ought to relieve the white population of their presence.

Mr. President, whenever any power, constitutionally or unconstitutionally, assumes the responsibility of liberating slaves where slaves are numerous, they establish as inexorably as fate a conflict between the races that will result in the exile or the extermination of the one race or the other. I know it. We have now about two hundred and twenty-five thousand slaves in Kentucky. Think you, sir, that we should ever submit to have those slaves manumitted and left among us? No, sir; no, never; nor will any white person in the United States of America where the slaves are numerous. If by unconstitutional legislation you should by laws which you shrink from submitting to the test of constitutionality in the courts, the moment you reorganize the white inhabitants of those States as States in the Union, they would reduce those slaves again to a state of slavery, or they would expel them and drive them upon you, or they would hunt them like beasts and exterminate them.

If at the time you commenced this war, you had announced as the national policy that was to prevail the measures and visionary schemes and ideas of some gentlemen on this floor, you should not have had a solitary man from the slave States to support you. You will unite the slave States by this conduct as one man, one woman, to resist your deadly policy.

March 19, 1862

Mr. Pomeroy of Kansas: I have noticed that

persons who have some constitutional  objections in regard to having free colored men among them, never

have any very severe difficulties to having slaves about them. Colored men are

as sweet as flowers in slavery, but if they are free they have a tremendous

odor, and men are anxious to colonize and to banish them. There are about

eleven thousand colored persons of whom three thousand are slaves. I do not

think we need to open a country for their colonization.

objections in regard to having free colored men among them, never

have any very severe difficulties to having slaves about them. Colored men are

as sweet as flowers in slavery, but if they are free they have a tremendous

odor, and men are anxious to colonize and to banish them. There are about

eleven thousand colored persons of whom three thousand are slaves. I do not

think we need to open a country for their colonization.

We have been told that slavery was established in Maryland, and that the laws of Maryland have been extended to the District. The law of Maryland was passed in 1715, and it limited slavery to two generations. As slavery was not perpetual in Maryland I would like to know who made it perpetual in this District.

If the Senate shall come to the strange conclusion that money must be paid, that $1 million must be appropriated to compensate the owners of the slaves, then I say let it be measured out in justice. There are families here holding slaves that have served their masters for forty years. Are you going to give the master of such a slave $300 and turn the slave loose without any settlement for his unpaid labor? To give a man $300 to rid himself of some old slave that he does not like to keep any longer, is an act of injustice that I think the Senate will not commit.

March 20, 1862

Mr. Willey of "Virginia:" I shall speak today as a border state man, as a representative of the loyal people of Virginia. Sir, in the name of two hundred thousand southwestern Virginians who have been immured for many months in the dungeons of rebellion at Richmond, I appeal to you today for your forbearance.

I remember what Webster said here in 1850: `There are men who, with clear perceptions, as they think, of their own duty, are disposed to mount upon some duty as a warhorse and to drive furiously on, and upon, and over all other duties that may stand in the way. There are men, in such times, who think human duties may be ascertained with the precision of mathematics. They deal with morals as with mathematics, and they think what is right may be distinguished from what is wrong with the precision of an algebraic equation. Men too impatient to wait for the slow progress of moral causes in the improvement of mankind.'

Mr. President, the question which I want to discuss is, is it wise, under the existing circumstances, to pass this bill? Sir, this bill is part of a series of measures, already initiated, all looking to the same ultimate result—the universal abolition of slavery by Congress.

Mr. President, I shall not trouble the Senate with any argument respecting the constitutional power of Congress to pass laws emancipating slaves. The arguments already made against this power have not been answered, and I believe they never will be. But I do not think the argument against the practicability of emancipation has been exhausted. I cannot understand these bills: They punish the traitor, indeed, but they only increase the burdens and taxes of the loyal people. Why thrust these questions upon the country and upon Congress now, when both are staggering beneath the pressure of exigencies involving the very integrity of our national existence? Sir, in no degree can the agitation and adoption of the policy contained in these measures contribute to the success of our arms, the peace of the country, or to the restoration of the Union. No, sir, the agitation of these questions must be mischievous. It will create strife and division and disturb the country.

The people of the South have been taught to believe that the object and design of the Republican party was to abolish slavery in all the States. These bills will be seized upon as evidence of this intention. They will say: `Look at their unconstitutional confiscation law. Look at the bill to make slaves free in the District. Especially will they point to sweeping resolutions of the great apostle of abolition, Senator Sumner, which by one dash of the pen, deprives every southern man of his slaves.

Mr. President, is it desired to make this a war of total extermination? Let us beware how we drive our friends in the South into the ranks of our adversary! One year's experience has taught us that a divided South was no contemptible foe. What will it be united? Seven hundred thousand square miles of fruitful territory, full of natural resources, inhabited by six millions of united, desperate people, may not be easily overcome and brought back to their allegiance.

Besides, sir, there is no necessity for driving these people to such desperate extremities. They love the old flag, they love the Union. Show them their rights under the Constitution will be respected and you will strike a blow more fatal to the rebel cause that a score of such victories as that at Fort Donelson.

I understand that Mr. Lincoln himself to be actuated by such principles. I understand that these were his principles long ago. Mr. Lincoln, in 1858, in his discussion with Mr. Douglas, at Quincy, used this language:

`We have a due regard to the actual presence of slavery among us, and the difficulties of getting rid of it in any satisfactory way, and all the constitutional obligations thrown about it. I suppose that, in reference to its actual existence in the nation and to our constitutional obligations, we have no right at all to disturb it in the States where it exists. . . We think the Constitution would permit us to disturb it in the District of Columbia. Still, we do not propose to do that, unless it should be on terms which I do not expect the Nation likely to agree to—the terms of making the emancipation gradual and compensating the unwilling owners.'

Mr. President, I ask Senators to consider what must be the practical

effects of emancipation. What then will be the effect upon the slave? Suppose

they are emancipated; what then? Are they freemen in fact? Will they have the

rights of freemen? Sir, such an idea is utterly fallacious. It will practically

amount to nothing. You cannot enact the slave into a freeman by act of

Congress. The servile nature of centuries cannot be eradicated by the rhetoric

of Senators. A freeman has the right of locomotion; he has the right of going

into any State, and of becoming the citizen of any State. Let me ask the

Senator from Illinois whether, if I set my slave free, he will allow him to

come to Illinois. Let me ask the same question of the Senators of Indiana. Sir,

the constitutions of both these States prohibit free negroes from becoming

citizens of those States, or even residents thereof; and that is the liberty

you propose for the slave.

Mr. President, I ask Senators to consider what must be the practical

effects of emancipation. What then will be the effect upon the slave? Suppose

they are emancipated; what then? Are they freemen in fact? Will they have the

rights of freemen? Sir, such an idea is utterly fallacious. It will practically

amount to nothing. You cannot enact the slave into a freeman by act of

Congress. The servile nature of centuries cannot be eradicated by the rhetoric

of Senators. A freeman has the right of locomotion; he has the right of going

into any State, and of becoming the citizen of any State. Let me ask the

Senator from Illinois whether, if I set my slave free, he will allow him to

come to Illinois. Let me ask the same question of the Senators of Indiana. Sir,

the constitutions of both these States prohibit free negroes from becoming

citizens of those States, or even residents thereof; and that is the liberty

you propose for the slave.

Now, sir, I ask, can the free negro be a freeman clothed with the rights of freemen in this country? In how many States is he entitled to the right of suffrage or to be a juror, or a judge, or to a seat in the Legislature; to make, interpret, or execute the laws of the State in which he lives? I understand there are some negroes living in the North who possess large estates, are well educated, and of good morals and manners. Do you receive them into your families on terms of equality? Do you give them your daughters in marriage? Why not? Are they not wealthy, intelligent, polite, and, for aught I know, handsome? Are not `all men born free and equal?'

Sir, I am not going to discuss the dogma of the natural equality of men. I am only referring to facts, fixed facts; and I say, right or wrong, naturally equal or naturally inferior, the negro never can be a freeman in this country, enjoying social and political equality.

We must take things as they actually exist. We shall not deserve the

name of statesman if we do not. Sir, would you recommend the Chinese to adopt a

republican form of government? Would you advise the native African, cannibals

and all, to organize a government on the model of the Constitution of the United States? The idea is preposterous. And now, sir, candidly considering the ignorance,

degradation, and helplessness of the four millions of slaves in the South, can

you desire their immediate emancipation? Would it not be an act of cruelty to

the slave? Sir, what would become of them? Think of it. Think of these four

millions of these degraded, helpless beings, without a dollar of money, without

an acre of land or an implement of trade or husbandry, without house or home,

thrust out upon the community to maintain themselves. Sir, they would starve to

death, or they would steal, or they would murder and rob. Better drive them

into the Gulf of Mexico at once, than perpetrate such a monstrous cruelty as

this upon them.

We must take things as they actually exist. We shall not deserve the

name of statesman if we do not. Sir, would you recommend the Chinese to adopt a

republican form of government? Would you advise the native African, cannibals

and all, to organize a government on the model of the Constitution of the United States? The idea is preposterous. And now, sir, candidly considering the ignorance,

degradation, and helplessness of the four millions of slaves in the South, can

you desire their immediate emancipation? Would it not be an act of cruelty to

the slave? Sir, what would become of them? Think of it. Think of these four

millions of these degraded, helpless beings, without a dollar of money, without

an acre of land or an implement of trade or husbandry, without house or home,

thrust out upon the community to maintain themselves. Sir, they would starve to

death, or they would steal, or they would murder and rob. Better drive them

into the Gulf of Mexico at once, than perpetrate such a monstrous cruelty as

this upon them.

And now you, men of the North, I beg to ask, what would be the

consequences of this wholesale emancipation on your own communities? How long

would it be until this miserable population, like the frogs of Egypt, would be infesting your kitchens, squatting at your gates, and filling your

almshouses? Sir, are you willing to receive them? If you set them free, you

must receive them. Will you extend your hand and receive them as coequals and co-laborers

in your fields and shops? Meantime, what will become of the cotton fields of

the South, and the cotton factories of the North? While you are increasing your

laborers, you will be destroying the sources of their employment.

And now you, men of the North, I beg to ask, what would be the

consequences of this wholesale emancipation on your own communities? How long

would it be until this miserable population, like the frogs of Egypt, would be infesting your kitchens, squatting at your gates, and filling your

almshouses? Sir, are you willing to receive them? If you set them free, you

must receive them. Will you extend your hand and receive them as coequals and co-laborers

in your fields and shops? Meantime, what will become of the cotton fields of

the South, and the cotton factories of the North? While you are increasing your

laborers, you will be destroying the sources of their employment.

The answer to all this is, transport and colonize the emancipated slave in some tropical country. What then? Whither shall they be sent? Where shall we find a tropical country for four millions of slaves? And where shall we find the money to pay for a territory sufficient to settle four millions? How much will it cost? Then, sir, there is the cost of transportation, the cost of outfitting and the cost of houses to be built, and the cost of implements of trade and husbandry, the cost of food and clothing for the first year at least. And then, sir, our task has just begun. We must provide for their continued supervision, direction, and protection. And how long must this continue? How long will it be before this mass of ignorant and servile population will become capable of self-government and self-subsistence? How many generations will it be before he is clothed with the independence of freemen? Who can pay this debt? The accumulating millions of the current war debt, now rising mountain high, sink into mole hills before the Atlas-like dimensions of the sum that will be required for the accomplishment of this stupendous scheme of philanthropy.

I am happy to perceive that the northern mind is beginning to appreciate the difficulties surrounding these schemes of immediate emancipation. I find the following in a recent edition of the New York World:

`The negro race is multiplying with such rapidity in this country that, in a few generations more, its relation to the white population will have become a question of fearful magnitude. At the time of our first census, in 1790, there were in the United States only seven hundred and fifty thousand negoes; at our last census, in 1860, there were four millions. Before the end of the century there will be a negro population of thirteen millions. What is now wanted is an enlightened system, for bringing to bear on a collective mass of plantation negroes all the educative and humanizing influences of which their condition is susceptible. To furnish facilities for such an experiment is work worthy of an enlightened government.'

I cannot close these remarks without making these observations: Sir, what is the object of the present war? For what are we fighting? To what purpose are we taxing the people and expending the treasures of the country? Why are thousands of our sons yielding their lives on the battlefield? I had supposed it was for the preservation of the Union. I had supposed, in the language of the President, it was to `protect, maintain, and defend the Constitution.' I had supposed the Congress meant what it said when, at the last session, it declared that the object of the war was to suppress the rebellion and restore the Union and the Constitution and nothing more. The flag as it was, the Union as it was, the Constitution as it was—this was the universal sentiment.

What now? We are told that the rebels have forfeited their rights under the Constitution, that the States in rebellion have abdicated their authority as States, and may be no longer recognized as members of the Confederacy. What is to become of the loyal inhabitants of the South, of Virginia, Louisiana, Tennessee, North Carolina? We may well pray, save us from our friends. It would have been better to have been crushed to death at once beneath the iron heel of the rebellion.

March 24, 1862

Mr. Davis again: The natural law gives no right of

property to man in anything save what he is using at the moment. It is the

public law that gives security to the owner of property. My right to land and

to a slave is based on the same law. African slaves were introduced more than

two centuries ago into this country by Las Casas, in humanity to the Indian

race. The Spaniards were enslaving the Indians and making them work in mines,

and treating them with great cruelty; and in tenderness toward the Indian race,

Las Casas himself originated the slave trade in Africans, and he marshalled the

way to the introduction of the negro from his native country to this country to

serve here as a slave. Slavery was in that way introduced into the thirteen

colonies, except Pennsylvania. Then our difficulties with the mother country

commenced. Slavery was existing as an institution and slaves were recognized as

property. They united together as slaveholding colonies to resist the aggressions

of England. Then the present Constitution came to be formed. The existence of

slavery is recognized in that instrument under a mild phrase, but just as

clearly and as certainly recognized as though the term slave

itself were used. Hence it is a delusion, not true in fact or law, when

gentlemen assume that slavery is local and freedom is universal.

Mr. Davis again: The natural law gives no right of

property to man in anything save what he is using at the moment. It is the

public law that gives security to the owner of property. My right to land and

to a slave is based on the same law. African slaves were introduced more than

two centuries ago into this country by Las Casas, in humanity to the Indian

race. The Spaniards were enslaving the Indians and making them work in mines,

and treating them with great cruelty; and in tenderness toward the Indian race,

Las Casas himself originated the slave trade in Africans, and he marshalled the

way to the introduction of the negro from his native country to this country to

serve here as a slave. Slavery was in that way introduced into the thirteen

colonies, except Pennsylvania. Then our difficulties with the mother country

commenced. Slavery was existing as an institution and slaves were recognized as

property. They united together as slaveholding colonies to resist the aggressions

of England. Then the present Constitution came to be formed. The existence of

slavery is recognized in that instrument under a mild phrase, but just as

clearly and as certainly recognized as though the term slave

itself were used. Hence it is a delusion, not true in fact or law, when

gentlemen assume that slavery is local and freedom is universal.

As Chief Justice John Marshall decided, the slave trade and the existence of slaves as property was recognized at one time throughout the whole civilized world, according to the usages and practices of every European Power that had a colony either on the continent or on the islands of North America. It therefore results that slavery is the normal condition in the United States, and the abolition of slavery the exception.

I say that the prohibitions of the Constitution restrict Congress's power to legislate freedom for slaves living in the District. One of the rights secured by the Constitution is the right of property; the Congress cannot take a person's property without due process which means just compensation, and then can take it only for a public use.

There is a very different spirit and there are very different purposes now in the dominant party in this chamber, in relation to slavery, than what was declared a few months ago. If the present policy had been declared before or immediately after Bull Run, what now would be the condition of this Government and of your Army? I know that the Army of the West is not engaged in a crusade against slavery.

Just days after Bull Run, the Senate, by overwhelming margin, passed this resolution: `This war is not being prosecuted for the purpose of overthrowing or interfering with the rights of established institutions of the seceded States, but to defend and maintain the supremacy of the Constitution and preserve the Union, and that when these objectives have been met the war shall cease.' Now, sir, if you intended to make that pledge in good faith, you have no right now to enlarge the purposes of the war.

Mr. Clark of New Hampshire: Does the Senator understand this to be a purpose of war that we are now about?

Mr. Davis: Yes, sir; this is a purpose of war now. It is an entering wedge. You want to get the head in, and then you intend to push the monster through. That is what you are after. If there was to be no other movement upon slavery, we never should have heard of this bill to abolish slavery in the District. This is but a preliminary experiment. You are endeavoring to experiment now how far you can go, and how far the moderate men in your party will go with you.

You are men. You act as all parties do. The possession of power intoxicates you as it intoxicates others. You abuse it; you trample upon the Constitution in the exercise of powers of Government that it gives you; you commit acts of injustice and oppression; you go to such extremes and excesses as to revolt the public mind, and sooner or later the people will rise and overthrow you as they have overthrown the parties that preceded you.

Now, Mr. President, there is one gentlemen in the Republican party who understands. Mr. Doolittle of Wisconsin. As he justly remarked, there is a question beyond that of manumitting slaves in the District; and that question is the separation of the races. He said, very correctly, that God, who made both races, has in effect decreed that they shall be separate. They can never live together in any considerable numbers except as master and slave, and all the puny efforts of man can never repeal that law. Whenever liberation comes, separation must follow. If it does not follow, the war of races is inevitable, and one or the other must and will be exterminated. We have two hundred and twenty-five thousand slaves in Kentucky. They are owned mostly by Union men. If you proceed upon the principle of manumitting all the slaves in that State that have belonged to person who were in the rebel army, you will find that it is impossible, that you will have no power to enforce the law, and you will never enforce it. There is no being in that state who would not rise up in revolt.

What right have you to force your views on the people of the

District? Why do you not go out into the city and hunt up the blackest,

greasiest, fattest old negro wench you can find and lead her to the altar of

Hymen? You do not believe in any such equality, nor do I. Yet your emissaries

proclaim here that the slaves, when you liberate them, shall be citizens, shall

be eligible to office in this city. A few days ago I saw several negroes

thronging the open door listening to the debate on this subject, and I suppose

in a few months they will be crowding white ladies out of these galleries.

What right have you to force your views on the people of the

District? Why do you not go out into the city and hunt up the blackest,

greasiest, fattest old negro wench you can find and lead her to the altar of

Hymen? You do not believe in any such equality, nor do I. Yet your emissaries

proclaim here that the slaves, when you liberate them, shall be citizens, shall

be eligible to office in this city. A few days ago I saw several negroes

thronging the open door listening to the debate on this subject, and I suppose

in a few months they will be crowding white ladies out of these galleries.

I have some statistics. The free negroes in the District in the 1860 census was 11,500, the slaves 3,000. All these 11,500 were not manumitted here; how did they come here? This is a general receptacle for the free negroes, refugees negroes from Virginia and Maryland. The white population is 37,000. Are you willing to take that portion of free negroes into your communities? If you are so humane, buy the slaves from their owners at a fair price and take them to your homes, and there make them your neighbors, if you choose, your equals in politics and in the social circle. When you do this the world will give you credit, but now it is all cant, it is all ambition.

March 25, 1862

Mr. Wilson of Massachusetts: The Constitution gives Congress the "power to exercise exclusive legislation in all cases whatsoever," over this ceded ten miles square we call the District of Columbia. Instead of providing a code of humane laws for the government of the Capital of a Christian nation, Congress enacted, in 1801, that the laws of Maryland and Virginia, as they then stood, should be in force in the District. By this act, the indecent slave codes became the laws of republican America for the government of its chosen capital. By this act of national legislation the people of Christian America began the first year of the nineteenth century by accepting for the government of their capital, the colonial legislation, enacted for the wild hordes of Africa, which the colonial and commercial policy of England forced upon Maryland and Virginia.

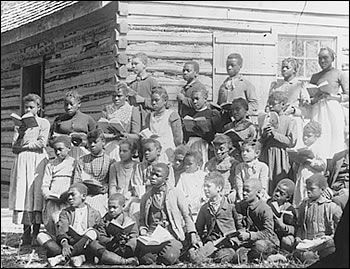

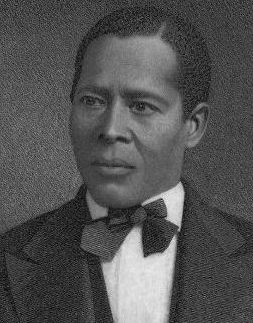

In spite of oppressive and cruel laws which have pressed with merciless force upon the black race, bond and free, slavery, has grown weaker, and the free colored stronger, at every decade that passes. Within the last half century, the free colored population of the District has increased from four to twelve thousand. In spite of the degrading influences of oppressive statutes, and a perverted public sentiment, this free colored population, as it increased in numbers has increased also in property, in churches, in schools, and all the means of social, intellectual, and moral development. This despised race is industrious and law-abiding, loyal to the Government and its institutions. Today the free colored men of the District possess hundreds of thousands of dollars of property. They are compelled to pay for the support of the public schools for the instruction of white children from which their own children are excluded by law, custom, and public opinion. Some of these free colored men are distinguished for intelligence, business capacity, and the virtues of grace that adorn men of every race.

This bill proposes to strike the chains from the limbs of three thousand bondmen in the District, to erase the name slave from their foreheads, to convert them from personal chattels into free men, to place them in the ranks of free colored men

The Senator may have the right to talk about colored folk in Kentucky, but he knows nothing of free colored persons in the District. As a class, the free colored people of this District are not worthless, vicious, thriftless, indolent, vagabonds, criminals, paupers, nor are they a charge and pest upon society. Do they not support themselves? Support their churches, their schools? Do they not take care of their sick and their dying? Do they not bury their dead free of public charge? What right does the Senator from Kentucky have to come into this chamber and attempt to deter us from executing this act of emancipation, by casting undeserved reproaches upon the free colored people of this District?

The Senator from Kentucky chooses to indulge in vague talk about the deadly resistance which the whole white population of the slaveholding States would make to unconstitutional encroachments. Why, sir, does he indulge in such allusions? Have not the American people the constitutional right to relieve themselves from the shame of upholding slavery in their capital? Sir, I tell the Senator from Kentucky that the day has passed by in the Senate of the United States for intimidation, threat, or menace, from the champions of slavery. |

I remind the Senator from Kentucky that the people, whose representatives we are, now realize in the storms of battle that slavery is, and ever must be, the relentless and unappeasable enemy of free institutions in America, of the unity and perpetuity of the Republic. Slavery plunged the nation into the fire and blood of rebellion. The loyal people of America have seen hundreds of thousands of brave men abandon their peaceful pursuits, leave their quiet homes, follow the flag of their country to the field, to do a soldier's duty, and fill, in need be, soldiers' graves. They know that slavery has caused all this.

The Senator from Kentucky proposes the bill be amended so that the emancipated may be removed from the District. He tells us that where slaves are numerous, they establish a conflict between the races that will result in the exile or extermination of one or the other. `I know it!` exclaims the Senator. How does he know it? In what age and in what country has the emancipation of one race resulted in the extermination of the one race or the other? Nearly a quarter century ago, England struck the chains from eight hundred thousand of her West Indies bondmen. There has been no conflict between the races. Other European nations have emancipated their colonial bondmen. No wars of races have grown out of these deeds of emancipation. The existence in Delaware of a large class of emancipated slaves has not produced a war of the races. The people of Delaware have never sought to hunt them down like beasts and exterminate them.

No, sir, no, sir, Emancipation does not lead to wars of the races. In our country enfranchisement of bondmen has tended to elevate both races, and has been productive of peace, order and public security. The bill, if it shall become law, will blot out slavery forever from the national capital, transform personal chattels into freemen, obliterate oppressive, odious, and hateful laws and ordinances, which press with merciless force upon persons of African descent.

Mr. Kennedy of Maryland: I shall content

myself with entering the most solemn protest against this bill. The census

figures show that we have the largest free colored population than any other

State. The six New England States, have 65,000 square miles of territory and,

in 1850, had 23,000 free colored persons living there. The little State of Maryland

Mr. President, I say in conclusion, that while we of Maryland avoided the rock of secession, still clinging to the Constitution upon which we were embarked, we may find ourselves drifting into the dark and overwhelming whirlpool of a relentless, unyielding, and reckless sectional policy, which will end forever the last hope of bringing together the dismembered and broken ties that bound this great and prosperous nation in one fraternal bond of union and power. In the name of my State, I protest against this measure. |

Mr. Saulsbury of Delaware: I will remark now only that

if this bill passes it is to pass by the votes of Senators from the

non-slaveholding States, gentlemen representing States that are not afflicted

with the great curse of a free negro population. I propose this amendment: That

the said persons liberated, within thirty days thereof, be transported to the

States of Maine, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut,

Vermont, and New York.

Mr. Saulsbury of Delaware: I will remark now only that

if this bill passes it is to pass by the votes of Senators from the

non-slaveholding States, gentlemen representing States that are not afflicted

with the great curse of a free negro population. I propose this amendment: That

the said persons liberated, within thirty days thereof, be transported to the

States of Maine, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut,

Vermont, and New York.

The yeas and nays were called for and the Secretary proceeded to call the role. The result was then announced: yeas 2, nays 31.

Mr. Harlan of Iowa: Mr. President, I regret very much that Senators depart so far from the proprieties as to make the allusions that they do. I refer to the allusions to white people embracing colored people as their brethren and the invitations of Senators to white men and women to marry colored people.

I do not deem it proper to enter into a labored investigation of the probabilities of amalgamation of the white with the negro race if the negroes should be set free. How is it in point of fact? Do you find white gentlemen and white ladies marrying the free negroes that are now in this District? I have known but three cases and in all those men marrying wenches have been citizens of slave States, where, I doubt not they acquired their tastes. (Laugher) Liberating the negroes carries with it no obligation to marry their wenches to white men.

Mr. Saulsbury: I will say to the Senator from Iowa that that man wherever he exists within this Union—who would make the emancipation of the slave population a paramount consideration to the preservation of his country is a disloyal man; and he cannot cover up his disloyalty under the cry of Union, or by wrapping around himself the American flag and thanking God that he is not as other men or even as these poor slaveholders. (Applause in the galleries).

The Presiding officer called for order.

Mr. Saulsbury: Senators, abandon now at once and forever your schemes of wild philanthropy and universal emancipation; proclaim to the people of this whole country everywhere that you mean to preserve the Union established by Washington and Jefferson and Madison, and the fathers of the Republic, and the rights of the people as secured by the Constitution and your Union never can be destroyed; but go on with your wild schemes of emancipation, throw doubt and suspicion upon every man simply because he fails to look at your questions of wild philanthropy as you do, and the God of heaven only knows after wading through scenes before which even the horrors of the French Revolution pale their fires, what ultimately may be the result.

March 31, 1862

Mr. Sumner of Massachusetts: Mr. President, with unspeakable delight I hail this measure and the prospect of its speedy adoption. It is the first installment of that great debt which we all owe to an enslaved race, and will be recognized in history as one of the victories of humanity.

As the moment of justice approaches we are called upon to meet the

question of ransom of the slaves of the Capital. At some other time the great

question of emancipation in the States may be more fitly considered, together

with those questions the Senator from Wisconsin has allowed himself to take