The year 1862 began with high hopes in Washington that the Confederate capital at Richmond, Virginia, would be captured and the war brought to a successful conclusion. A large, well-equipped force, the Army of the Potomac, had been organized and in the spring set out for the Union enclave at Fort Monroe, Virginia. Commanded by General George B. McClellan, the Army of the Potomac then marched up the Virginia peninsula to lay siege to Richmond; other smaller commands remained in northern Virginia and the Shenandoah Valley to maintain security for the Federal capital.

However, instead of Union success, the spring and summer saw a string of Confederate victories in Virginia. In May and June a small Confederate force commanded by General Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson separately defeated three small union commands in the Shenandoah Valley, threatening the security of Washington. To better defend the capital and possibly assist in the attack on Richmond, President Abraham Lincoln ordered that these three commands be consolidated into a force to be known as the Army of Virginia.

During the early summer, in the Seven Day's Battles, the Army of the Potomac was driven back from the Confederate capital by the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, commanded by General Robert E. Lee. The Federal government then decided to withdraw the Army of the Potomac and join it with the Army of Virginia. However, before both Union commands could unite, Lee's army marched north and in late August defeated the Army of Virginia at the Battle of Second Bull Run, thirty-five miles south of the Union capital. As summer came to an end, the Union had not captured Richmond and the Confederates appeared poised to capture Washington.

Although the year had seen one Confederate victory after another in Virginia, months of campaigning had taken its toll on the Army of Northern Virginia. Lee's command had suffered many casualties who would be difficult to replace. It was also short on rations and supplies, and literally thousands of Lee's troops were without sufficient clothing, especially shoes. As the Army of Northern Virginia prepared to embark on another major

campaign, only its military organization prevented it from resembling a mob of hungry vagabonds.

In the days after Second Bull Run, the government in Washington prepared for an expected Confederate assault and Lee pondered his options. Insufficient numbers of troops, rations, ammunition, and other supplies prevented him from either attacking or engaging in a siege of the city. Washington was surrounded by extensive fortifications, bristling with artillery, and defended by large numbers of troops.

Lee could not afford to remain idle. It would be only a matter of time before Union forces reorganized and embarked on yet another advance into Virginia. To draw the Union Army out of its entrenchments around Washington and into the open, Lee planned to march north of Washington into Maryland. A Confederate movement north of the Potomac River would threaten both Washington and Baltimore and force the Federal government to devote large numbers of troops to defend those cities. (Submitted Article Details of Lee's effort to distract General George B. McClellan before Antietam Special Order 191, Position Paper)

In early September Lee wrote to Confederate President Jefferson Davis that the Army of Northern Virginia was not properly equipped for such a campaign, especially since thousands of its men were barefoot. Nevertheless, Lee thought that his army was strong enough to keep the enemy occupied north of the Potomac until the approach of winter would make an enemy advance into Virginia  difficult, if not impossible. Richmond would be safe, at least until the following spring. On 4 September the Army of Northern Virginia crossed the Potomac River near Leesburg to the martial strains of "Maryland, My Maryland" and marched on to Frederick, Maryland. difficult, if not impossible. Richmond would be safe, at least until the following spring. On 4 September the Army of Northern Virginia crossed the Potomac River near Leesburg to the martial strains of "Maryland, My Maryland" and marched on to Frederick, Maryland.

Fifty-five-year-old Virginian Robert E. Lee was the son of Revolutionary War hero General Henry "Light Horse Harry" Lee. Robert E. Lee graduated second in the West Point Class of 1829 and later served in the Mexican War, in which he was slightly wounded. He was superintendent of West Point from 1852 to 1855. In April 1861 Lee resigned his commission, hoping to remain out of the coming conflict. However, after Virginia seceded from the Union in late May, Lee accepted an appointment as commander of Virginia military forces. Later he served as military adviser to Jefferson Davis. On 1 June 1862, Davis assigned Lee to command the force defending Richmond, which would soon become known as the Army of Northern Virginia. During the summer he led that army in the successful Battles of the Seven Days and Second Bull Run. Now, in early September, Lee led the Army of Northern Virginia north to the Potomac and into Maryland. He entered Maryland not on horseback but in an ambulance, for almost a week earlier he had fallen and broken a small bone in one hand and strained the other. His hands had been placed in splints, with his right arm in a sling. It would be another week before he would be able to ride at all, and then only with a courier often leading his horse.

At the beginning of the Maryland Campaign, the Army of Northern Virginia was organized into two infantry commands, or "wings."

Forty-one-year-old General James Longstreet commanded one wing of the army. A native of South Carolina, Longstreet had graduated from West Point in 1842. Like Lee, he was wounded in the Mexican War. At the beginning of the Civil War, Longstreet resigned his U.S. Army commission and accepted a commission as brigadier general in the Confederate Army, commanding an infantry division. In October of the same year Longstreet was appointed major general and during the summer of 1862 commanded a wing in the Army of Northern Virginia. Longstreet's wing contained the divisions of General Lafayette McLaws and Richard H. Anderson, as well as Brig. General David R. Jones, General John B. Hood, and General John G. Walker.

Thirty-eight-year-old Virginian Stonewall Jackson commanded Lee's other wing. Jackson had graduated from West Point in 1846 and resigned his commission almost ten years later to become an instructor at the Virginia Military Institute. When the Civil War broke out, Jackson accepted a colonelcy in the Virginia militia. Shortly thereafter, while a brigadier general at the First Battle of Bull Run, he earned the sobriquet Stonewall by standing firm against Union attacks. Jackson's wing included the divisions of General Ambrose P. Hill, General Daniel H. Hill (Jackson's brother-in-law), Brig General John R. Jones commanding Jackson's division, and Brig. General A. R. Lawton commanding Ewell's Division (the name given to the division previously commanded by Maj. General Richard S. Ewell).Jackson also spent time traveling in an ambulance. Shortly after entering Maryland, he was injured when his horse reared up and fell on him. Jackson was severely bruised and unable to ride for several days.

In addition to the two infantry wings, Lee's army included a cavalry division commanded by 29-year-old General James E. B. Stuart, a Virginian and 1854 graduate of West Point. Stuart's division also included three batteries of artillery commanded by Capt. John Pelham.

The artillery of the Army of Northern Virginia at the Battle of Antietam totaled approximately 246 guns, at least 82 of which were rifled, organized into batteries of 4-6 guns each. A battalion of several batteries was attached to each division, and four battalions of several batteries each were attached to the army's reserve artillery, command by Brig. General William N. Pendleton. The strength of the Army of Northern Virginia in July was almost 50,000 men. However, by the Battle of Antietam in mid-September, combat casualties, sickness, and straggling had reduced those numbers to roughly 35,000.

After crossing the Potomac, the main portion of the Army of Northern Virginia reached Frederick by 7 September. The following day Lee issued a proclamation to the people of Maryland in which he promised "to aid you in throwing off this foreign yoke" and to restore sovereignty to the state.

Meanwhile, the Federal government at Washington was moving to counter Lee's advance into Maryland. On 5 September the Army of Virginia was officially consolidated with the Army of the Potomac, with the whole to be commanded by 35-year-old General McClellan. A West Point graduate of 1846 and former classmate of General Jackson's, McClellan had resigned his commission in 1857. He served for a time with the Illinois Central Railroad and shortly before the Civil War was president of the eastern division of the Ohio and Mississippi Railroad. When war broke out, McClellan offered his services to the military forces of Ohio. In late 1861 he was summoned to Washington by President Lincoln, commissioned major general in the Regular Army, and appointed as general in chief of the Army.

Although McClellan was an excellent administrator and enormously popular with the troops, he was at constant odds with the Lincoln administration over military policy. In March 1862, when McClellan left Washington to accompany the Army of the Potomac to Fort Monroe, Lincoln relieved him as general in chief. (He retained command of the Army of the Potomac.) McClellan's continued bickering with the administration and the failure of his campaign before Richmond led to calls for his dismissal. It was, therefore, a surprise to many when Lincoln announced that McClellan would command the reorganized army during the Maryland Campaign. Lincoln believed that McClellan alone was capable of the complex task of quickly reorganizing and consolidating the two demoralized armies and then leading them immediately into battle. In addition to many regiments and batteries drawn from the defenses of Washington, the new elements of McClellan's army included the North Carolina Expeditionary Force of Maj. General Ambrose E. Burnside's IX Corps. Burnside's command had arrived in northern Virginia in July from operations along the coast of the Carolinas. In early September Brig. General Jacob D. Cox's Kanawha Division, which had arrived from western Virginia the previous month, was attached to the IX Corps.

When the War Department learned that Lee's army had crossed into Maryland, McClellan was ordered to pursue immediately. By 7 September he was leading the Army of the Potomac north in search of Lee.

Aware that McClellan's army was moving westward on a broad front toward Frederick, Lee had to decide where to meet the enemy for battle. Lee's army had to reach the Shenandoah Valley eventually, because it was the only place where the army might rest and replenish its sustenance supplies. But if the army moved immediately across the Potomac into the Valley, without offering battle, Lee expected McClellan to directly follow. To prevent that, McClellan had to be induced to abandon the offensive and stand on the defensive, and only a general battle might accomplish that. Offering McClellan battle on the line of the Monacacy River, in front of Frederick, was impossible, because McClellan's army was so large it could easily turn the flanks of Lee's smaller army. Lee needed a battlefield where his flanks could not be turned and, scrutinizing his map he recognized the location of Sharpsburg on he Antietam as the place.

But Lee could not commit his army to battle on the line of the Antietam, as long as the Union garrisons at Martinsburg (5,000 men) and Harper's Ferry (10,000 men plus 1,200 cavalry) were capable of interfering with his line of retreat. These garrisons had to be neutralized first. Accordingly, Lee devised an audacious plan of action, which, if successful, would allow the Battle of Antietam to occur.

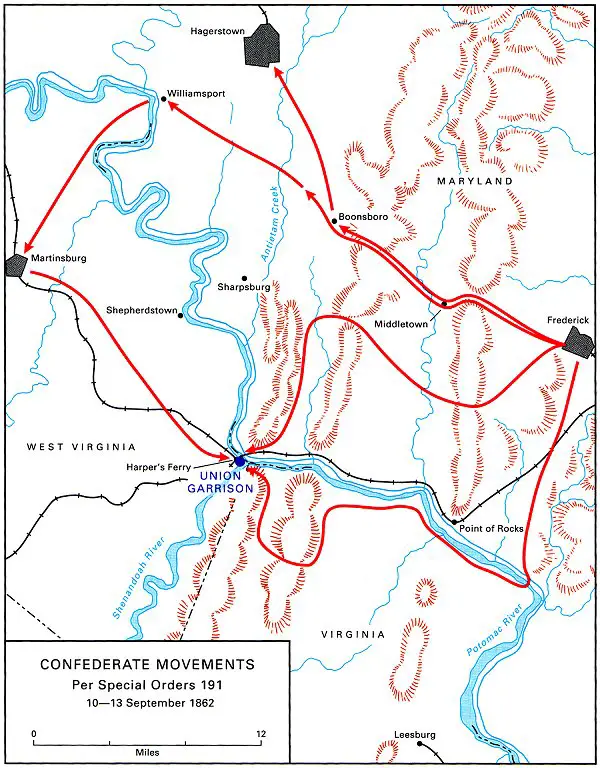

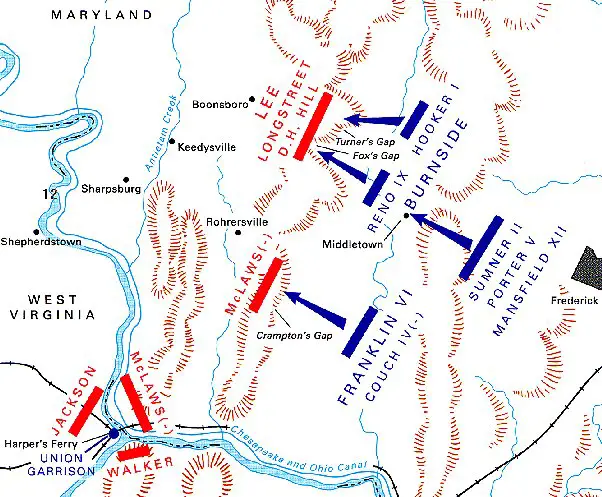

Lee, after consultation with Jackson, decided to capture the two garrisons. On 9 September Lee issued Special Orders 191, which explained the Harper's Ferry operation in detail, including the routes of march for the various units involved. Jackson, with the divisions commanded by J. R. Jones, Lawton, and A. P. Hill, was to recross the Potomac River at Williamsport, Maryland, and capture the garrison at Martinsburg. The divisions of McLaws and Anderson were to march through Pleasant Valley, directly to Maryland Heights, on the Elk's Ridge spur overlooking Harper's Ferry, while Walker's division crossed the Potomac into Loudoun County and blocked the river road leading from Harper's Ferry to Leesburg. Longstreet's command, followed by D.H. Hill's division, acting as rear guard, was to move according to circumstances to Boonesboro or Hagerstown, on the west side of Turner's Gap in the South Mountain, and wait there for the return of the detached forces. Maryland, and capture the garrison at Martinsburg. The divisions of McLaws and Anderson were to march through Pleasant Valley, directly to Maryland Heights, on the Elk's Ridge spur overlooking Harper's Ferry, while Walker's division crossed the Potomac into Loudoun County and blocked the river road leading from Harper's Ferry to Leesburg. Longstreet's command, followed by D.H. Hill's division, acting as rear guard, was to move according to circumstances to Boonesboro or Hagerstown, on the west side of Turner's Gap in the South Mountain, and wait there for the return of the detached forces.

The Confederate army departed Frederick on 10 September. Jackson's command marched to Williamsport, where it forded the Potomac while bands played "Carry Me Back to Ole Virginny." On 12 September, as Jackson approached Martinsburg, the Federal garrison there fled to Harper's Ferry. The following morning Jackson resumed his march; by the evening of 13 September, the time by which Lee had hoped the operation would be finished, the commands of Jackson, Walker, R. H. Anderson, and McLaws were surrounding Harper's Ferry.

On 12 September, only two days after the Confederate army's departure from Frederick, elements of the Army of the Potomac began entering that city. The following day McClellan himself arrived. The 80,000-man Union army was organized into three wings. Thirty-eight-year-old General Burnside commanded the army's right wing, consisting of the I Corps, led by General Joseph Hooker, and the IX Corps, led by Maj. General Jesse L. Reno. Sixty-five-year-old Maj. General Edwin V. Sumner commanded the center wing, which included Sumner's own II Corps and the XII Corps, commanded by Maj. General Nathaniel Banks. Because Banks had been retained in Washington to command the defense of the capital, the corps was placed under the temporary command of Maj. General Joseph K. F. Mansfield. Thirty-nine-year-old Maj. General William B. Franklin commanded McClellan's left wing, which included Franklin's own VI Corps and the division of Maj. General Darius Couch. Couch's division had been part of the IV Corps, but that organization had recently been disbanded and Couch's division attached to Franklin's command. Brig. General Alfred Pleasonton commanded McClellan's cavalry division, which contained five brigades of cavalry. McClellan's field artillery consisted of approximately 300 guns, typically organized into batteries of 6 guns, each with several batteries assigned to each division. Almost 60 percent of McClellan's artillery was rifled.

After McClellan arrived at Frederick on the morning of 13 September, circumstances intervened on his behalf. That morning a Union enlisted man camping near town found several cigars around which was wrapped a copy of Lee's Special Orders 191. By early afternoon the document was in McClellan's hands.

McClellan recognized that the text of Lee's order seemed to confirm what scouts and civilians had already reported to him. Lee had split his army into separate columns: Jackson's crossing the Potomac at Williamsport, McLaws and Anderson moving to the Potomac in front of Harper's Ferry, while Lee's "main body" had moved through Turner's Gap and was reported marching toward Hagerstown. The situation seemed to call for an immediate and rapid forward movement in the direction of Pleasant Valley and the Potomac bridges in front of Harper's Ferry, where McClellan could cross over and cut off Lee's line of retreat. But, on second thought, McClellan became concerned that Pleasant Valley might be a trap, as Jackson and Lee might be lurking behind South Mountain, waiting to fall on his flank and rear. McClellan later wrote that he "immediately gave orders for a rapid and vigorous forward movement." but the pursuit did not occur that afternoon.

Earlier in the day the IX Corps had been sent to cross Catoctin Mountain and was approaching Middletown. McClellan ordered the IX Corps to continue to Turner's and Fox's Gaps on South Mountain the following morning. At 1820 McClellan also ordered the VI Corps to cross Crampton's Gap the following morning. Around midnight a confident McClellan sent a telegram to President Lincoln: "I have all the plans of the rebels, and will catch them in their own trap if my men are equal to the emergency." He added, "Will send you trophies." the following morning. Around midnight a confident McClellan sent a telegram to President Lincoln: "I have all the plans of the rebels, and will catch them in their own trap if my men are equal to the emergency." He added, "Will send you trophies."

McClellan's confidence about confronting Lee's army, however, came to be tempered by his mistaken belief that Lee's army outnumbered him. From a variety of sources, he was getting estimates of Confederate strength ranging from 80,000-200,000 men. Moreover, as McClellan telegraphed Washington, "Everything seems to indicate that they intend to hazard all upon the issue of the coming battle. They are probably aware that their forces are numerically superior to ours by at least 25 per cent." Observing that a general battle against such odds "might, to say the least, be doubtful," McClellan asked to be reinforced by troops stationed in defense of Washington. The administration responded by sending the V Corps, commanded by Maj. General Fitz John Porter.

On the evening of 13 September Lee received the news from Stuart's cavalry scouts that the Union army had reached Frederick. Stuart estimated Union strength to be 90,000. Shortly afterward Lee also learned from Stuart that, according to a local citizen, a copy of Special Orders 191 was in McClellan's hands. The Union army approaching the South Mountain gaps.

On 14 September McClellan's right wing, commanded by Burnside and consisting of Hooker's I Corps and Reno's IX Corps, fought its way to the top of South Mountain. By evening the Confederate defenders barely held their ground on the crest. During the fighting Reno was killed, and General Cox assumed command of the IX Corps. Six miles to the south, Franklin's VI Corps attacked Crampton's Gap. After a hard-fought battle with McLaws' defenders, Union forces occupied the gap. It had taken all day, but McClellan's army had captured one mountain gap and would probably force its way through the other two the following morning. McClellan was jubilant. He telegraphed the War Department, "It had been a glorious victory." When the results of the Battles of South Mountain reached the White House, Lincoln, who only a few days earlier had feared a Confederate attack on Washington, telegraphed McClellan: "Your dispatch of to-day received. God bless you and all with you! Destroy the rebel army, if possible."

Having watched the defense of the northern gaps, late in the evening Lee determined that the troops at hand were insufficient to prevent an expected Union attempt to cross the mountain the following morning. Consequently, he decided to end the campaign in Maryland and withdraw the troops then with him to Virginia by way of a Potomac River ford at Shepherdstown. But shortly thereafter Lee received the news that Union troops had taken Crampton's Gap. If the Union troops crossed through that gap the following morning, they could relieve the Union garrison at Harper's Ferry. To guard against the potential Union maneuver, Lee decided to halt his retreat near Sharpsburg and threaten any enemy force moving against McLaws' and Anderson's rear.

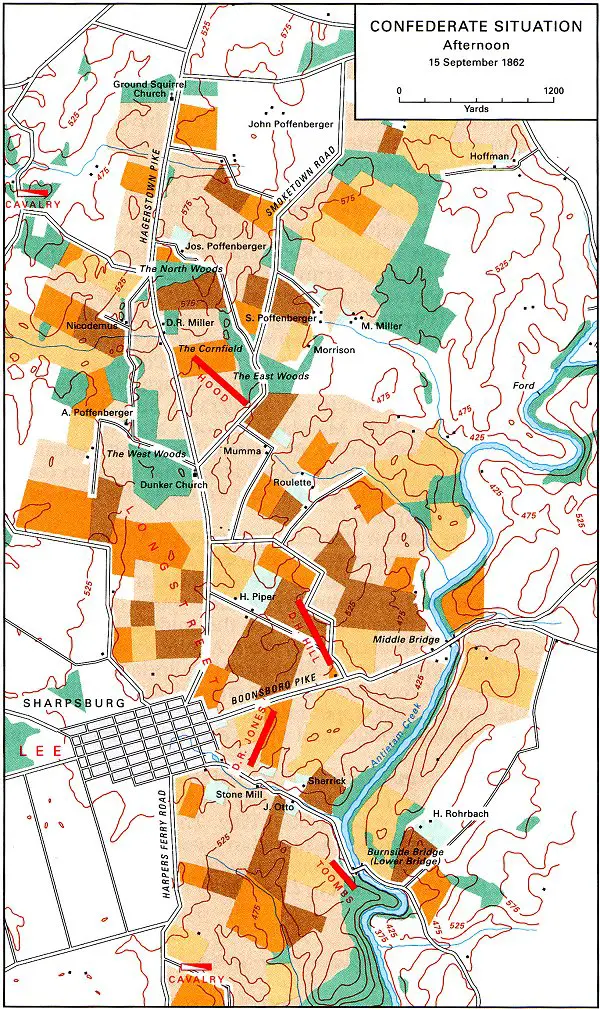

On the morning of 15 September Lee, along with Longstreet, D. R. Jones' and D. H. Hill's divisions, and a portion of Stuart's cavalry, reached Sharpsburg on Boonsboro Pike. The town is just east of Antietam Creek and only about three miles from the Potomac River. A bridge across the river had been destroyed earlier in the war, but the river could be crossed at Boteler's Ford, less than a mile downstream from Shepherdstown.

Around noon Lee received news of the surrender of the Harper's Ferry garrison. The surrender was announced to the army, which, according to Lee, "reanimated the courage of the troops." A short time later Stuart arrived to inform Lee of the large number of Union prisoners captured at Harper's Ferry and the vast amounts of supplies. With thousands of his men barefoot, Lee quickly responded, "General, did they have any shoes?" Pointing to a Confederate unit standing barefoot nearby, Lee told Stuart, "These good men need shoes."

With Harper's Ferry captured and the Confederate victors now marching to rejoin the army at Sharpsburg, Lee elected to remain in Maryland a little longer. Lee made a risky decision to remain north of the Potomac River and confront an enemy he believed to outnumber his army by two to one. On 15 September Lee had on hand at Sharpsburg only about 25,000 men. The Confederates at Harper's Ferry might add another 15,000 men, but it would be a day at least before these troops might rejoin the army at Sharpsburg. At Lee's back was the Potomac River. If Lee was driven back to Boteler's Ford by an aggressive enemy, it might mean disaster for the Confederates. Still, Lee was reluctant to withdraw from Maryland so soon after his "liberating" entry only a week earlier. And even though his command might be outnumbered, he had confidence that his men could hold their own against the Army of the Potomac. He decided to make a stand at Sharpsburg.

In 1862 three narrow stone bridges crossed Antietam Creek in the vicinity of Sharpsburg. A road from Keedysville on Boonsboro Pike crossed the stream at the northernmost, or upper, bridge near the mill of Philip Pry. A mile south of the upper bridge, Boonsboro Pike crossed over the middle bridge (now replaced by a modern highway bridge). A mile south of Sharpsburg, the lower bridge, now called Burnside Bridge, crossed the stream. Antietam Creek could also be crossed at Pry's Mill Ford, a half-mile south of the upper bridge; at Snavely's Ford, a mile south of the lower bridge; and at several other smaller farm fords.

Lee deployed his small command around Sharpsburg. The division of D. R. Jones was placed on high ground east of the town and south of Boonsboro Pike. The small brigade of Brig. General Robert Toombs was assigned to guard the lower bridge. Farther south, a portion of Stuart's cavalry guarded the army's right flank. Northeast of town, D. H. Hill's division was placed between the middle bridge and Dunker Church. (Also known as Dunkard Church, the small white structure belonged to a pacifist sect known as the Church of the Brethren. Outsiders called the congregation Dunkers or Dunkards because of a doctrine of three total immersions during baptism.) Hood's division was placed near Dunker Church. Surrounding Hood's command were three woodlots known as the West, North, and East Woods and a gently rolling farmland of cornfields, plowed fields, and pastures. On the opposite side of the pike from the church almost half a mile farther north was a thirty-acre cornfield that would gain notoriety in the battle. To guard the army's left flank, another portion of Stuart's cavalry was placed northwest of Dunker Church near the bend in the Potomac River. Lee established his headquarters in a tent on the western edge of town on Boonsboro Pike. Dunkard Church, the small white structure belonged to a pacifist sect known as the Church of the Brethren. Outsiders called the congregation Dunkers or Dunkards because of a doctrine of three total immersions during baptism.) Hood's division was placed near Dunker Church. Surrounding Hood's command were three woodlots known as the West, North, and East Woods and a gently rolling farmland of cornfields, plowed fields, and pastures. On the opposite side of the pike from the church almost half a mile farther north was a thirty-acre cornfield that would gain notoriety in the battle. To guard the army's left flank, another portion of Stuart's cavalry was placed northwest of Dunker Church near the bend in the Potomac River. Lee established his headquarters in a tent on the western edge of town on Boonsboro Pike.

McClellan's army began crossing the northern gaps of South Mountain on the morning of 15 September and marched toward Sharpsburg. To the south, Franklin's VI Corps, followed by Couch's division, crossed at Crampton's Gap. Franklin's mission had been to relieve the Harper's Ferry garrison; but some time after noon the mission changed when, as McClellan later wrote, "the total cessation of firing in the direction of Harper's Ferry indicated but too clearly the shameful and premature surrender of the post. McClellan ordered Franklin and Couch to halt at the western foot of South Mountain and await further orders.

McClellan's army began arriving on the east side of Antietam Creek on the afternoon of 15 September. Although a force of Confederates could be seen halted on the west side of the creek, McClellan believed that the enemy was in full retreat and would cross the Potomac River back into Virginia that night. McClellan established his headquarters on Boonsboro Pike about a mile south of Keedysville. While the cavalry halted on the heights east of the middle bridge, Maj. General Israel B. Richardson's and Brig. General George Sykes' divisions took positions opposite the bridge and Hooker's I Corps halted east of the upper bridge. Sumner, with Maj. General John Sedgwick's and Brig. General William French's divisions and Mansfield's XII Corps, halted at Keedysville. McClellan later said that he had hoped to make an attack that afternoon; but "after a rapid examination of the position, I found it was too late to attack that day. Instead, he spent the afternoon waiting for more troops to arrive, assigning positions for the troops to camp that night, and placing artillery batteries, including long-range rifled artillery, on the ridge overlooking the creek. That evening Cox's IX Corps arrived and was placed opposite the lower bridge. During the day McClellan had suspended the organization of Burnside's right wing and ordered Hooker to report directly to him rather than to Burnside. Burnside was assigned command of the left wing of the army, which consisted of only the IX Corps.

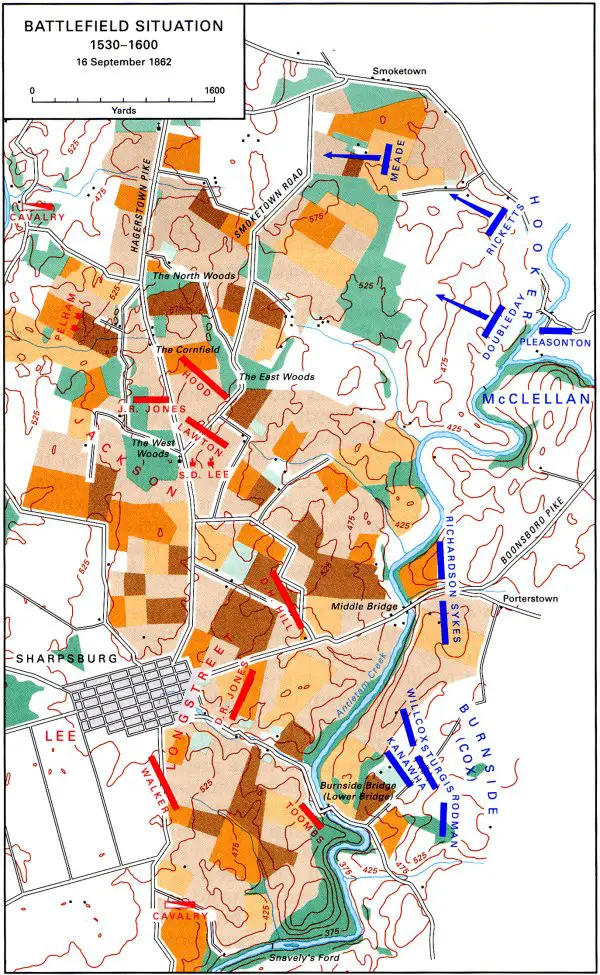

On the morning of 16 September McClellan, still expecting the Confederates to be mostly across the river in Virginia, wrote to his wife: "Have reached thus far and have no doubt delivered Penna and Maryland. All well and in excellent spirits. McClellan also sent a telegram to Washington: "This morning a heavy fog has thus far prevented our doing more than to ascertain that some of the enemy are still there. Do not yet know in what force. Will attack as soon as situation of the enemy is developed. When the fog cleared, McClellan spent most of the morning riding along his line, "examining the ground, finding fords, clearing approaches, and hurrying up ammunition and supply-trains. Around noon Maj. General George W. Morell's division of the V Corps arrived, accompanied by Porter himself, and was halted near Keedysville.

While McClellan continued to prepare to attack, Jackson and the divisions of J. R. Jones and Lawton arrived at Sharpsburg, rejoining Jackson's third division, commanded by D. H. Hill. Jackson's fourth division, that of A. P. Hill, remained at Harper's Ferry to secure captured property and parole the large number of prisoners (about 12,000). Walker's division of Longstreet's command also arrived from Harper's Ferry and halted a short distance south of the town.

By 1330 McClellan was finally ready to go on the offensive, but he was reluctant to commit a large portion of his army to a frontal attack. Instead, he ordered Hooker's I Corps, stationed by the upper bridge, to cross Antietam Creek and if possible to turn Lee's left flank. McClellan later started in his report of the battle:

My plan for the impending engagement was to attack the enemy's left with the corps of Hooker and Mansfield, supported by Sumner's and, if necessary, by Franklin's; and as matters look favorably there, to move the corps of Burnside against the enemy's extreme right, upon the ridge running to the south and rear of Sharpsburg, and having carried their position, to press along the crest towards our right; and whenever either of these flank movements should be successful, to advance our center with all the forces then disposable.

However, if McClellan had indeed formulated such a plan before the battle, he apparently failed to impart it to Hooker, who was under the impression that the I Corps with roughly 8,500 men was acting alone. Hooker's corps consisted of three divisions commanded by Brig. Gens. Abner Doubleday, James B. Ricketts, and George G. Meade. It was not until approximately 1530 or 1600 that the divisions of Meade and Ricketts crossed at the upper bridge and began marching toward Hagerstown Pike while Doubleday's division crossed nearby Pry's Mill Ford.

Hooker's command had not gone much over half a mile when Hooker began to have doubts about attacking the Confederates with only his corps. Hooker informed McClellan that if he were not reinforced, or unless a simultaneous attack was made on the Confederate right flank, "the rebels would eat me up. McClellan promised reinforcements and ordered Sumner's XII Corps, commanded by Mansfield, from Keedysville to support Hooker. Sumner was also to be prepared to send the II Corps from Keedysville for the same purpose the next morning. To be closer to the impending action, McClellan moved his headquarters to the home of Philip Pry, about half a mile south of the upper bridge, just west of Boonsboro Pike.

Lee, Longstreet, and Jackson were meeting in the center of Sharpsburg when a courier brought word that Union troops were crossing Antietam at the upper bridge. Around the same time they also received news of enemy movements near the lower bridge. To meet the northern threat, Lee sent Jackson with J. R. Jones' command toward Dunker Church to join with Hood. Lawton was initially ordered to support Toombs' brigade at the lower bridge; but after Lee determined that there was no Union attempt to cross the lower bridge, Lawton was sent to join Jackson. Walker's command remained south of Sharpsburg, available to support Toombs if necessary.

Shortly before dark Hooker's columns, preceded by skirmishers from Meade's division, reached the East Woods. Hood's division opened a lively skirmish with Meade's men, but darkness and a drizzling rain ended the confrontation. Hood then withdrew to the West Woods, south of Dunker Church. Jackson extracted a promise from Hood that his division would return to the front the moment it was called upon.

Leaving Brig. General Truman Seymour's brigade of Meade's division in the East Woods, the remainder of Hooker's corps moved into bivouac just east of Hagerstown Pike and north of the Joseph Poffenberger home. Hooker, still nervous about confronting an enemy that he believed to outnumber him, informed McClellan that his attack would begin at dawn. He also asked that reinforcements be sent to him before the attack.

During the night McClellan ordered Franklin's VI Corps, still near Crampton's Gap, to join the main army at Sharpsburg. Couch's division was ordered to remain in place. Around midnight, per McClellan's orders, the 7,500-man XII Corps crossed Antietam Creek and by 0200 encamped about two miles north of the East Woods, joining Hooker's I Corps.

Facing the threat of an attack the following morning, Lee ordered A. P. Hill's division at Harper's Ferry to march for Sharpsburg at first light. Hill was to leave a small force behind to complete the removal of captured property.

The Battle September 17 1862

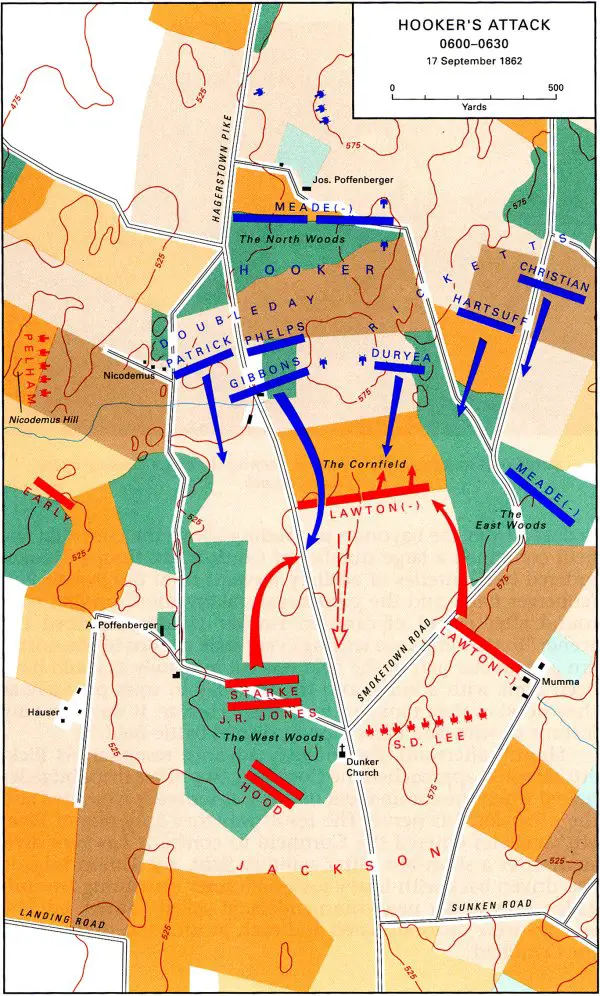

Shortly before daylight on 17 September Hooker's corps began to stir, initiating heavy firing between the pickets of both sides. By roughly 0600 the rain had ceased, and the I Corps began its advance south through a low-lying morning mist. Hooker stated that this immediate objective was to reach high ground almost a mile to the south (site of the present-day Visitor Center). While Doubleday's division marched south along Hagerstown Pike, Ricketts' division moved west of Smoketown Road. The brigades of Col. Albert L. Magilton and Lt. Col. Robert Anderson  of Meade's division waited in reserve near the North Woods. Seymour's brigade, also of Meade's division, remained in an advanced position in the southwest corner of the East Woods. In addition to Hooker's own artillery placed on high ground near the Joseph Poffenberger farm, his advance was also supported by long-range rifled guns on the heights east of Antietam Creek. These guns enfiladed Jackson's lines, dropping rounds randomly along Hagerstown Pike. of Meade's division waited in reserve near the North Woods. Seymour's brigade, also of Meade's division, remained in an advanced position in the southwest corner of the East Woods. In addition to Hooker's own artillery placed on high ground near the Joseph Poffenberger farm, his advance was also supported by long-range rifled guns on the heights east of Antietam Creek. These guns enfiladed Jackson's lines, dropping rounds randomly along Hagerstown Pike.

Under heavy fire from Union artillery, Jackson's command waited. The division of J. R. Jones was west of Hagerstown Pike, about 500 yards north of Dunker Church. Farther west, the brigade of Brig. General Jubal A. Early, part of Lawton's division, supported Stuart's cavalry. East of the pike, on the southern edge of the Cornfield, Lawton extended Jackson's line toward the East Woods. South of this position, near the home of Samuel Mumma, a portion of Lawton's command protected Jackson's right flank.

While Union artillery kept up a steady fire into Jackson's position, Confederate guns quickly responded. Along Nicodemus Hill, fourteen guns of Pelham's artillery opened fire into Brig. General John Gibbon's brigade of Doubleday's division. One of Hood's artillery battalions, commanded by Col. Stephen D. Lee and directly in the path of the Union advance, fired from a knoll just east of Hagerstown Pike and opposite Dunker Church. As the gunners on both sides kept up a lively fire, a civilian spectator noted, "The cannonade, reverberating from cloud to mountain and from mountain to cloud, became a continuous roar, like the unbroken roll of a thunder-storm.

Jackson's men did not have long to wait. Doubleday's and Ricketts' divisions soon reached the Miller farm and halted north of the Cornfield. The corn stood six feet high, but Hooker deduced from the bayonets protruding above the corn that the field contained a large number of Confederate troops. Hooker ordered two batteries of artillery forward from the Joseph Poffenberger farm, and the guns began raking the Cornfield with round after round of canister. Hooker vividly described the scene: "In the time I am writing every stalk of corn in the northern and greater part of the field was cut as closely as could have been done with a knife, and the slain lay in rows precisely as they stood in their ranks a few moments before. It was never my fortune to witness a more bloody, dismal battle-field.

Shortly afterward, the infantry advance resumed. As Ricketts' division approached the Cornfield, two of his three brigades halted when the commander of one was seriously wounded and the other lost his nerve. The result was that only one of Ricketts' brigades entered the Cornfield to confront Lawton's division. After a short but bitter standup fight, the Union brigade was driven back with heavy losses. Ricketts' remaining two brigades, now under new commanders, attacked Lawton; but the assaults were uncoordinated and each in turn was driven from the Cornfield.

While Ricketts' brigades fought in the eastern portion of the Cornfield, Doubleday's division fought in the western portion. An officer in Doubleday's command afterward wrote, "Men, I cannot say fell; they were knocked out of the ranks by dozens. Near Hagerstown Pike, Doubleday's men struck the left of Lawton's command and drove the Confederates back. A portion of J. R. Jones' division then attacked Doubleday, but it was driven back. After losing many casualties, Lawton's command also fell back to join D. R. Jones. The bloody Cornfield was in Union hands.

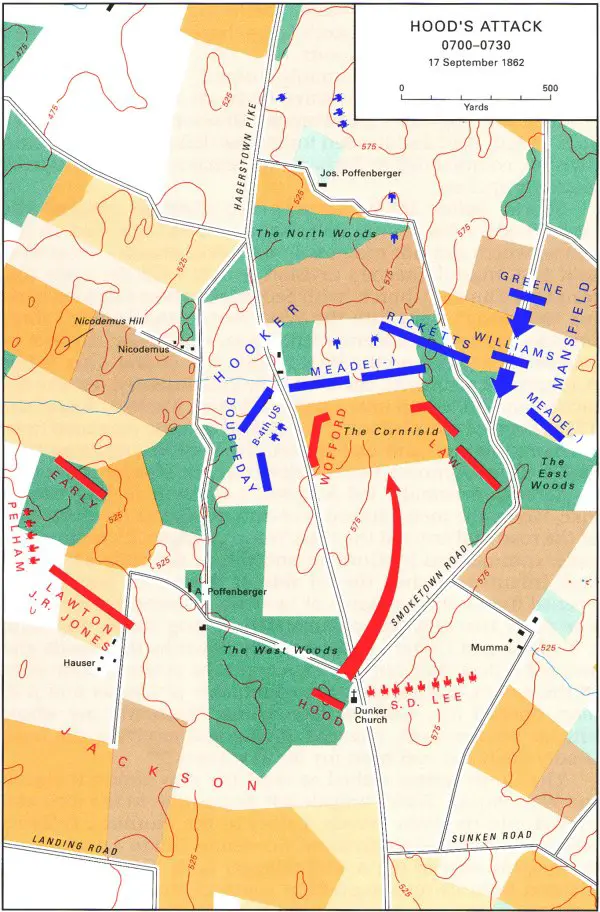

By 0700 over half of Jackson's command had been killed or wounded. J. R. Jones left the field after being stunned by the explosion of artillery shell. Brig. General William E. Starke, a brigade commander in Jones' command, was killed, the first Confederate general to be killed or mortally wounded during the battle. With his line collapsing, Jackson called on Hood's division for assistance.

Hood's men were preparing breakfast in the West Woods southwest of Dunker Church when they received orders to move at once to the front. The command quickly departed the woods and headed north with Col. William T. Wofford's brigade on the left and Col. Evander M. Law's brigade on the right. Doubleday's and Ricketts' divisions had resumed their advance when they were suddenly attacked by Hood's men. A Union Officer remembered, "A long and steady gray line, unbroken by the fugitives who fly before us, comes sweeping down through the woods around the church. They raise the yell and fire. It is like a scythe running through our line. 'Now save, who can.' It is a race for life that each man runs for the cornfield.

The left of Hood's division drove into the Cornfield, where another round of violence exploded. Hood later wrote, "It was here that I witnessed the most terrible clash of arms, by far, that has occurred during the war. As his men pressed forward, Hood's left flank came under fire from Doubleday's troops, who had fallen back to the west side of Hagerstown Pike. Battery B, 4th U.S. Artillery, also west of the pike, opened fire on the Confederates. The guns fired canister at a range of less than twenty-five yards, throwing splintered pieces of fence rails and men alike into the air. The Confederates who survived the blast began shooting down the gunners.

While part of Hood's command fought along the pike, the 1st Texas Infantry pushed through the Cornfield toward the Miller farmhouse, where Magilton's and Anderson's brigades of Meade's division had arrived earlier. The one-sided confrontation resulted in the Texans' suffering over 80 percent casualties and retreating to the Cornfield.

Meanwhile, the right of Hood's division entered the East Woods. There, it confronted Mansfield's newly arrived XII Corps, which McClellan had ordered to support Hooker the day before. Mansfield, thinking that his command was firing on Hooker's men, rode in front of his line to halt the firing and was mortally wounded. Brig. General Alpheus S. Williams, one of Mansfield's division commanders, assumed command of the corps and launched a counterattack into the Cornfield. Hood's command was driven back to the West Woods.

While Williams' division halted in the Cornfield, the other division of the XII Corps, commanded by Brig. General George S. Greene, detached one brigade to support Williams. Greene's two remaining brigades continued south on Smoketown Road. Colonel Lee's guns quickly withdrew, and Greene halted on a plateau east of Dunker Church. It was around this time that Hooker received a slight wound in the foot and turned over command of the I Corps to Meade. Meade, believing that the XII Corps was arriving to relieve Hooker's corps, began withdrawing the I Corps toward the North Woods.

As the fighting momentarily paused, McClellan ordered Sumner to send two of his three divisions to support Hooker. Sumner led Sedgwick's and French's divisions across the creek at Pry's Mill Ford and headed for the battlefield. Sumner's third division, commanded by Richardson, remained east of the creek guarding artillery.

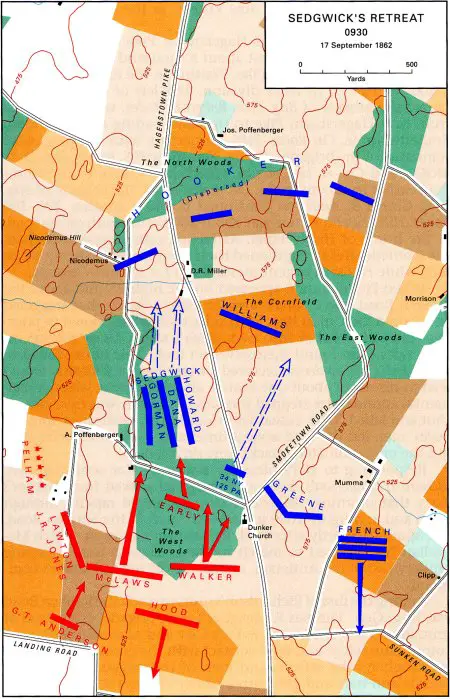

Shortly before 0900 Sumner's two divisions reached the East Woods. After a brief halt, the command resumed its advance, which did not progress in a unified manner. It split first around Greene's division, which held the open plateau near Dunker Church, with Sedgwick's three brigades moving to Greene's right into the West Woods and French's three brigades moving to Greene's left. Then, within the advance of Sedgwick's division on the West Woods, one of Brig. General Willis A. Gorman's regiments, the 34th New York Infantry, became detached and ended up near Dunker Church. There, it found the 125th Pennsylvania Infantry, which had become separated from Williams' division and had entered the West Woods some time earlier. Thus, Sumner's two divisions did not attack together.

Sumner personally led Sedgwick's division to Hagerstown Pike, where the men climbed post-and-rail fences on either side of the road and entered the West Woods. Sedgwick's leading brigade, commanded by Gorman and minus the stray 34th New York Infantry, reached the far side of the woods and quickly opened fire on the remnants of Jackson's command to the west. The other two brigades, commanded by Brig. Gens. Napoleon J. T. Dana and Oliver O. Howard, lay down in the woods and awaited orders. As Gorman's men appeared at the western edge of the woods, troops from the commands of Lawton and J. R. Jones opened fire. Gorman later wrote, "Instantly my whole brigade became hotly engaged, giving and receiving the most deadly fire it has ever been my lot to witness.

The Confederates rushed to meet the new Union threat in the West Woods. Early's brigade left its position to the west and moved into the West Woods. Earlier in the morning, Pelham's artillery had shifted south from Nicodemus Hill to a position on the heights west of the A. Poffenberger farm. Lee sent Walker's division from its reserve position south of Sharpsburg and the division of McLaws newly arrived from Harper's Ferry. Joining these divisions was the brigade of Col. George T. Anderson of D. R. Jones' division.

These Confederates, almost 8,000 strong, charged into the West Woods, first overrunning the isolated 34th New York and 125th Pennsylvania Infantries, then striking the left and rear of Sedgwick's division. Dana's and Howard's brigades leapt to their feet and tried to meet the attack, but it was too late. Like dominoes, they began to tumble northward with the Confederates in close pursuit. Gorman's brigade was also attacked, but it had more time to react and turned to meet the threat. Acting as a rear guard, Gorman's command withdrew northward, stopping now and then to fire a volley at its pursuers.

The remnants of Sedgwick's division fled across the Miller farm, where they sought the protection of Hooker's I Corps artillery. Williams' division in the Cornfield and Union artillery stopped the Confederates and drove them back to the West Woods. Sumner's attack into the West Woods had been a disaster. In less than thirty minutes, Sedgwick had been wounded and more than 40 percent of his division had been either killed or wounded. Confederates and drove them back to the West Woods. Sumner's attack into the West Woods had been a disaster. In less than thirty minutes, Sedgwick had been wounded and more than 40 percent of his division had been either killed or wounded.

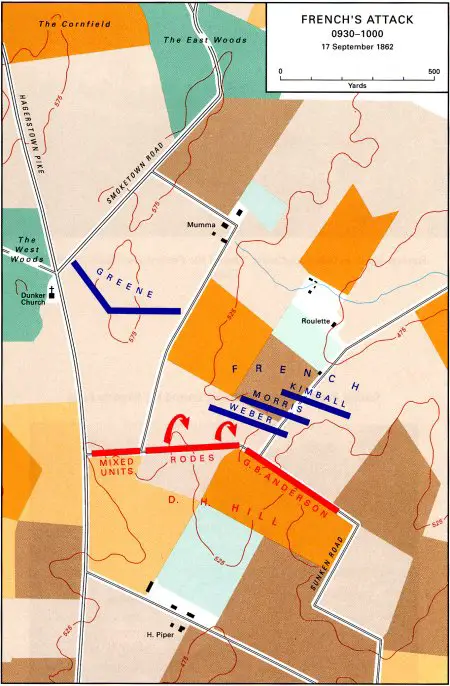

As Sedgwick's division was collapsing, French's 5,700-man division, having split to the left of Sedgwick's advance into the West Woods and cheered on by the martial music of regimental bands, crossed the Mumma and Roulette farms and advanced toward an old farm road, now known as the Sunken Road or Bloody Lane.

The Sunken Road joins Hagerstown Pike 500 yards south of Dunker Church, runs east about a thousand yards, and then turns south to Boonsboro Pike. Waiting in the road were almost 2,500 men of D. H. Hill's division. The left of Hill's line contained the brigade of Brig. General Robert E. Rodes, which extended from near Hagerstown Pike to the lane leading to the William Roulette home. On Rodes' left, connecting with the pike, were remnants of the brigades of Brig. General Roswell S. Ripley, Col. D. K. McRae, and Col. A. H. Colquitt, which had fought in the Cornfield earlier in the morning. On Rodes' right, the brigade of Brig. General George B. Anderson continued the line another 200-300 yards. Hill's headquarters was about 300 yards south of the road, at the home of Henry Piper. As French's division approached, the Confederates strengthened their position by piling up fence rails while Hill sent urgent messages to Lee for more troops.

When French's men appeared on the high ground above the Sunken Road, the Confederates let loose a volley that staggered and halted the Union line. Both sides then settled down to pouring volley after volley into each other's ranks. Many officers on both sides soon found themselves on foot, their horses killed or wounded. G. B. Anderson received a wound in the foot that would lead to his death about one month after the battle. When a regimental commander stepped forward to replace Anderson, he was shot and killed. With casualties mounting on both sides, some of Rodes' men left the road several times and charged French's line; but the uncoordinated attacks were driven back.

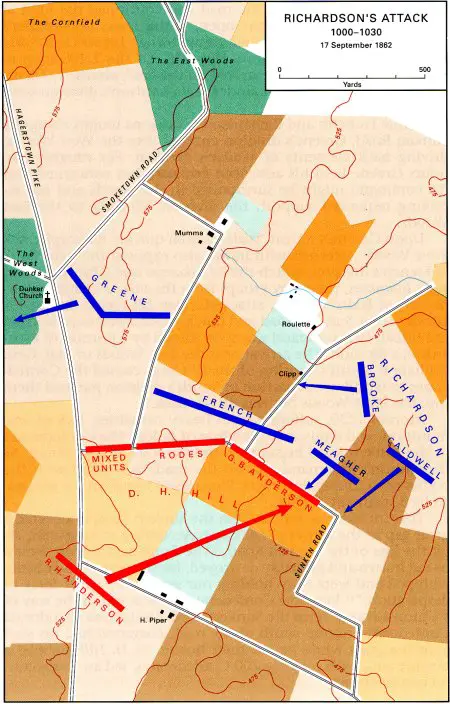

Responding to Hill's pleas for assistance, Lee sent Maj. General Richard H. Anderson's division, which had arrived from Harper's Ferry that morning. Anderson's men advanced rapidly through town and at roughly 1000 joined Hill's men in the Sunken Road. Shortly afterward, Richardson's division, which McClellan had ordered to march to the battlefield from guarding artillery east of the Antietam, arrived on the left of French's command.

Among the first of Richardson's units to reach the Sunken Road was Brig. General Thomas F. Meagher's Irish Brigade, composed of immigrants recruited in New York City and Massachusetts. "On coming into close and fatal contact with the enemy," according to Meagher, "the officers and men of the brigade waved their swords and hats and gave three hearty cheers for their general, George McClellan, and the Army of the Potomac. The Irishmen fired several volleys at the Confederates in the Sunken Road then charged up to the road and continued the fight at close range. Standing in the open, entire ranks of Meagher's men were shot down. Meagher, injured when his stricken horse fell on him, was carried from the field. Of the 1,400 men in Meagher's brigade when it arrived on the field, almost 1,000 lay dead or wounded. The remainder of Richardson's division soon arrived to join the fray.

While French's and Richardson's divisions fought along the Sunken Road, Greene's division charged into the West Woods, driving back elements of Walker's division. For roughly two hours Greene held his advanced position; but concerned that his command might be surrounded in the woods and not receiving requested support, the division fell back to the East Woods.

Upon Greene's retreat, Walker's men quickly reoccupied the West Woods. Greene's withdrawal also exposed the right flank of French's division, which the 3d Arkansas and 27th North Carolina Infantries, joined by groups from the mixed commands to the left of Rodes' brigade, attacked. French halted his attack on the Sunken Road and quickly faced westward to meet the threat. His command was soon joined by a portion of Richardson's division. The arrival near the East Woods of Maj. General William F. Smith's division of the IV Corps caused the Confederates to withdraw. A portion of Smith's division pursued them into the West Woods but was driven back.

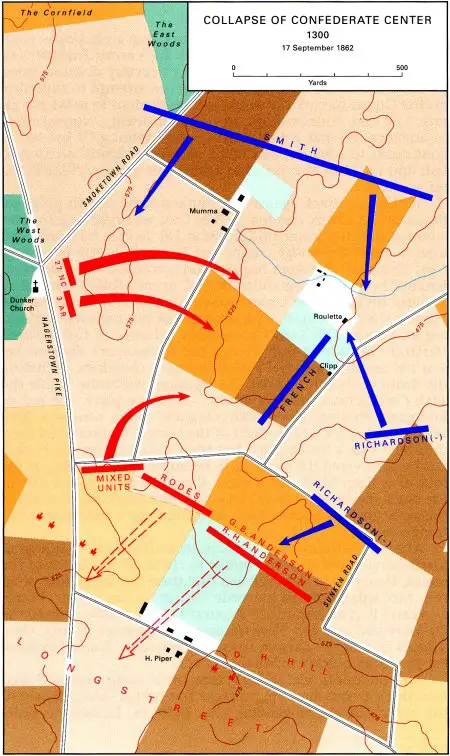

Around 1230, suffering from heavy casualties, lack of ammunition, and a misunderstanding of orders, the Confederates in the Sunken Road began to withdraw toward Sharpsburg. As Richardson's command crossed the road, now filled with the bodies of its former defenders, Richardson was mortally wounded by a fragment of shell.

The Confederate retreat from the Sunken Road uncovered a great gap in the center of Lee's line. According to Longstreet, after the loss of the Sunken Road, "The Confederate army would be cut in two and probably destroyed, for we were already badly whipped and were only holding our ground by sheer force of desperation. Very few Confederates now stood in the way of a Union advance from the Sunken Road. Seeing two abandoned Confederate cannon south of the road, Longstreet had his staff man the guns while he led their horses. D. H. Hill grabbed a musket and, with roughly 200 Confederates, led an unsuccessful counterattack.

With the Confederate center broken, one great Union push might have destroyed what was left of Lee's army. Franklin's IV Corps, Porter's V Corps, and the army's cavalry division stood poised for action. But McClellan made no attempt to capitalize on the Union success. "It would not be prudent to make the attack," he said, "our position on the right being ... considerably in advance of what it had been in the morning. Instead of continuing to advance, McClellan ordered Richards' division to halt and to "hold that position against the enemy. Lee's center was safe.

While the attack against the Sunken Road was in progress, Burnside's IX Corps, commanded by Cox, was attacking Toombs' command at the lower bridge. (Map 13) Toombs had only 400 men to hold the bridge, supported by another 100 from Brig. General Thomas F. Drayton's brigade and a company of men from Jenkins' brigade, commanded by Col. Joseph Walker, both of D. R. Jones' division. The Union attack began about 1000, but the assaults were piecemeal, with only one or two regiments attacking at a time. The 11th Connecticut Infantry of Col. Edward Harland's brigade of Brig. General Isaac P. Rodman's division began the assault; but after suffering heavy casualties, including the death of its commander, the regiment withdrew. While the 11th Connecticut Infantry attack was taking place, the rest of Rodman's division, along with a brigade of the Kanawha Division, searched for a ford south of the bridge. Rodman had been informed that a ford existed less than a mile below the bridge, but he discovered the crossing to be impracticable, being at the foot of a steep bluff rising more than 160 feet on the side of the creek. Rodman's command continued south and crossed at the waist-deep Snavely's Ford, two-thirds of a mile below the bridge.

After the withdrawal of the Connecticut troops, an aide from McClellan arrived near the bridge to check on the status of the attack. He reported to McClellan that there had been little progress. McClellan ordered Burnside "to assault the bridge at once and carry it at all hazards. Around 1100 Burnside ordered the 2d Maryland and 6th New Hampshire Infantries of Brig. General Samuel D. Sturgis' division to cross the bridge. Toombs' defenders, however, quickly drove them back.

Around noon McClellan's aide once again reported that Burnside's troops had yet to cross the bridge. McClellan sent the army's inspector general, Col. Delos B. Sackett, to order Burnside, at the point of the bayonet if necessary, to capture the bridge immediately. McClellan instructed Sackett to remain with Burnside until the attack was successful.

Burnside next ordered the 51st New York and 51st Pennsylvania Infantries, also of Sturgis' division, to attempt to cross the bridge. Around 1300 the two regiments, supported by a howitzer positioned near the bridge abutment, charged across the bridge and reached the opposite bank. (Map 14) About the same time, Rodman's division made its crossing at Snavely's Ford. North of the bridge, several companies of the 28th Ohio Infantry of the Kanawha Division waded across the creek to the west bank. With the crossing of Burnside's troops at the bridge and other Union troops crossing above and below, Toombs' defense ended and the remnants of his command fell back toward Sharpsburg. and below, Toombs' defense ended and the remnants of his command fell back toward Sharpsburg.

It had taken three hours for the IX Corps to secure a crossing, and it would be another two hours before Burnside could get the entire corps across the creek. McClellan was unhappy with the delay and ordered Burnside to continue his attack. Around 1500 the IX Corps began climbing the slopes toward Sharpsburg. As the troops approached the town, a Union signal detachment east of Antietam Creek signaled to Burnside, "Look out well on your left; the enemy are moving a strong force in that direction. It is unknown whether Burnside actually saw the warning message.

The approaching Confederates were elements of A. P. Hill's division arriving from Harper's Ferry. Hill had left the brigade of Brig. General Edward L. Thomas at Harper's Ferry to continue removing captured supplies, but he himself headed toward Sharpsburg with his five remaining brigades. Around 1430, after a seventeen-mile forced march, the head of Hill's command reached Sharpsburg; Lee quickly ordered it toward Burnside's advancing columns. (Hill's attack map.) While the brigades of Col. J. M. Brockenbrough and Brig. General William D. Pender guarded Hill's right, the brigades of Brig. Gens. L. O'B. Branch, Maxcy Gregg, and J. J. Archer charged into Burnside's left. The strenuous march had seriously depleted their strength, however, and the three attacking Confederate brigades numbered fewer than 2,000 men. In fact, Archer's brigade alone numbered only 350 men

While Brig. General Orlando B. Willcox's division, on the right of Burnside's attack, continued its advance to the outskirts of Sharpsburg, the sudden attack on the Union left halted Rodman's division. A portion of the Kanawha Division was ordered up the slope to support Rodman, but the troops had difficulty distinguishing friend from foe in the battle smoke. Troop identification was made even more difficult because some of Hill's men were wearing portions of Union uniforms captured at Harper's Ferry. In the confusion the portion of the Kanawha Division ordered to support Rodman was outflanked by Gregg and fell back.

For the IX Corps' effort to climb the hill to Sharpsburg, it suffered 2,000 casualties, including General Rodman, killed early in the attack. Rodman was the third Union general officer to be killed or mortally wounded this day. Toward the end of the fighting, Branch was killed, bringing to three the number of Confederate general officers killed or mortally wounded in the battle.

It was now around 1700 and growing dark. Unsure of the size of the Confederate force attacking his left, Burnside ordered the IX Corps to withdraw to the creek. As the sun set on what would become known as the bloodiest single day of the war, the IX Corps established a defensive perimeter near the lower bridge. Lee's exhausted troops on the heights above the bridge were content to remain in place.

The following morning, 18 September, the two armies remained in position. McClellan wrote, "To renew the attack again on the 18th or defer it, with the chance of the enemy's retirement after a day of suspense, were the questions before me. McClellan decided to wait and issued orders to renew the attack on 19 September. Lee, however, was ready to keep up the fight. An additional 5,000-6,000 stragglers had caught up with the army; according to one of Lee's officers, the Confederate commander hoped to turn McClellan's flank near the bend of the Potomac River west of Nicodemus Hill. Due to the large amount of Union artillery in the area, the plan was abandoned Unable to outflank McClellan on the Maryland side of the river, Lee withdrew his army to Virginia during the night of 18 September, hoping to recross the Potomac at Williamsport and attack McClellan's rear. The plan, however, was thwarted by the poor physical condition of his army; Lee decided to remain in Virginia

On the morning of 19 September McClellan discovered that the Confederates had withdrawn. A feeble Union pursuit resulted in a sharp fight at Boteler's Ford the following day, but McClellan was content to remain in Maryland and claim victory. Lee's army withdrew into the Shenandoah Valley to continue to gather supplies.

Weeks passed. In early October Lincoln visited the Union army near Sharpsburg to urge McClellan to cross into Virginia and give battle. McClellan, however, insisted that he needed more men and supplies before beginning another campaign. On 6 October Lincoln telegraphed McClellan to "cross the Potomac and give battle to the enemy or drive him south

On 10 October, while the Army of the Potomac remained in the Sharpsburg area, 1,800 men of Stuart's cavalry crossed the Potomac near Williamsport and reentered Maryland on an armed reconnaissance. The troops rode to Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, then eastward, gathering intelligence and much-needed horses while pursued by McClellan's cavalry. After circling around McClellan's encamped army, Stuart's men recrossed the Potomac near Leesburg on 12 October.

McClellan was still at Sharpsburg on 25 October, when he wired to Washington that he remained unable to move because his horses were suffering from sore-tongue and fatigue. An exasperated Lincoln responded: "I have just read your dispatch about sore-tongued and fatigued horses. Will you pardon me for asking what the horses of your army have done since the battle of Antietam that fatigues anything?"

The Army of the Potomac finally began to cross the Potomac River on 26 October but did not complete the crossing for almost a week. Lincoln finally reached the end of his patience and on 7 November relieved McClellan of command and replaced him with Ambrose Burnside.

|

|