HEADQUARTERS PROVISIONAL ARMY,

Charleston, S.C., April 27, 1861.

SIR: I have the honor to submit the following detailed report of the bombardment and surrender of Fort Sumter and the incidents connected therewith:

Having completed my channel defenses and batteries in the harbor necessary for the reduction of Fort Sumter, I dispatched two of my aides at 2.20 p.m., on Thursday, the 11th of April, with a communication to Major Anderson, in command of the fortification, demanding its evacuation. I offered to transport himself and command to any port in the United States he might elect, to allow him to move out of the fort with company arms and property and all private property, and to salute his flag in lowering it. He refused to accede to the demand. As my aides were about leaving Major Anderson remarked that if we did not batter him to pieces he would be starved out in a few days, or words to that effect. This being reported to me by my aides on their return with his refusal, at 5.10 p.m., I deemed it proper to telegraph the purport of his remark to the Secretary of War. In reply I received by telegraph the following instructions at 9.10 p.m.: “Do not desire needlessly to bombard Fort Sumter. If Major Anderson will state the time at which, as indicated by him, he will evacuate, and agree that in the mean time he will not use his guns against us unless ours should be employed against Fort Sumter, you are authorized thus to avoid effusion of blood. If this, or its equivalent, be refused, reduce the fort as your judgment decides to be most practicable.”

At 11 p.m. I sent my aides with a communication to Major Anderson based on the foregoing instructions. It was placed in his hands at 12.45 a.m. 12th instant. He expressed his willingness to evacuate the fort on Monday at noon if provided with the necessary means of transportation, and if he should not receive contradictory  instructions from his Government or additional supplies, but he declined to agree not to open his guns upon us in the event of any hostile demonstrations on our part against his flag. This reply, which was opened and shown to my aides, plainly indicated that if instructions should be received contrary to his purpose to evacuate, or if he should receive his supplies, or if the Confederate troops should fire on hostile troops of the United States, or upon transports bearing the United States flag, containing men, munitions, and supplies designed for hostile operations against us, he would still feel himself bound to fire upon us, and to hold possession of the fort. instructions from his Government or additional supplies, but he declined to agree not to open his guns upon us in the event of any hostile demonstrations on our part against his flag. This reply, which was opened and shown to my aides, plainly indicated that if instructions should be received contrary to his purpose to evacuate, or if he should receive his supplies, or if the Confederate troops should fire on hostile troops of the United States, or upon transports bearing the United States flag, containing men, munitions, and supplies designed for hostile operations against us, he would still feel himself bound to fire upon us, and to hold possession of the fort.

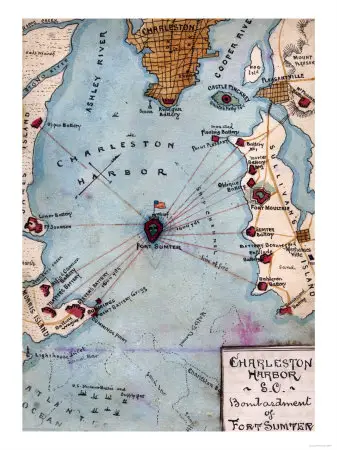

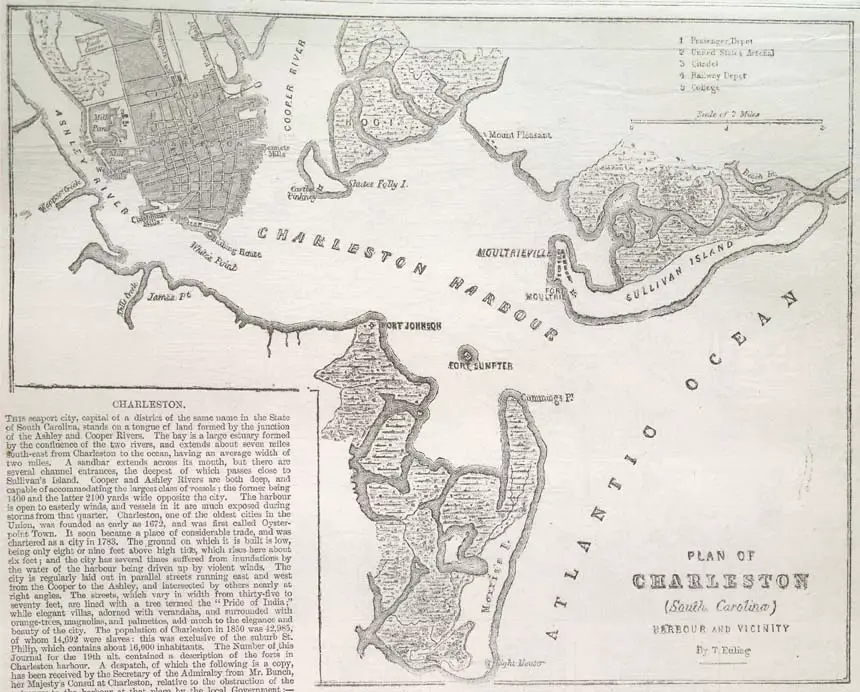

As, in consequence of a communication from the President of the United States to the governor of South Carolina, we were in momentary expectation of an attempt to re-enforce Fort Sumter, or of a descent upon our coast to that end from the United States fleet then lying at the entrance of the harbor, it was manifestly an imperative necessity to reduce the fort as speedily as possible, and not to wait until the ships and the fort should unite in a combined attack upon us. Accordingly my aides, carrying out my instructions, promptly refused to accede to the terms proposed by Major Anderson, and notified him in writing that our batteries would open upon Fort Sumter in one hour. This notification was given at 3.20 a.m. of Friday, the 12th instant. The signal shell was fired from Fort Johnson at 4.30 a.m. At about 5 o'clock the fire from our batteries became general. Fort Sumter did not open fire until 7 o'clock, when it commenced with a vigorous fire upon the Cummings Point iron battery. The enemy next directed his fire upon the enfilade battery on Sullivan's Island, constructed to sweep the parapet of Fort Sumter, to prevent the working of the barbette guns and to dismount them. This was also the aim of the floating battery, the Dahlgren battery, and the gun batteries at Cummings Point.

The enemy next opened on Fort Moultrie, between which and Fort Sumter a steady and almost constant fire was kept up throughout the day. These three points - Fort Moultrie, Cummings Point, and the end of Sullivan's Island, where the floating battery, Dahlgren battery, and the enfilade battery were placed - were the points to which the enemy seemed almost to confine his attention, although he fired a number of shots at Captain Butler's mortar battery, situated to the east of Fort Moultrie, and a few at Captain James' mortar batteries at Fort Johnson.

During the day (12th) the fire of my batteries was kept up most spiritedly, the guns and mortars being worked in the coolest manner, preserving the prescribed intervals of firing. Towards evening it became evident that our fire was very effective, as the enemy was driven from his barbette gun which he attempted to work in the morning, and his fire was confined to his casemated guns, but in a less active manner than in the morning, and it was observed that several of his guns en barbette were disabled. During the whole of Friday night our mortar batteries continued to throw shells, but, in obedience to orders, at longer intervals. The night was rainy and dark, and as it was almost confidently expected that the United States fleet would attempt to laud troops Upon the islands or to throw men into Fort Sumter by means of boats, the greatest vigilance was observed at all our channel batteries, and by our troops on both Morris and Sullivan's Islands.

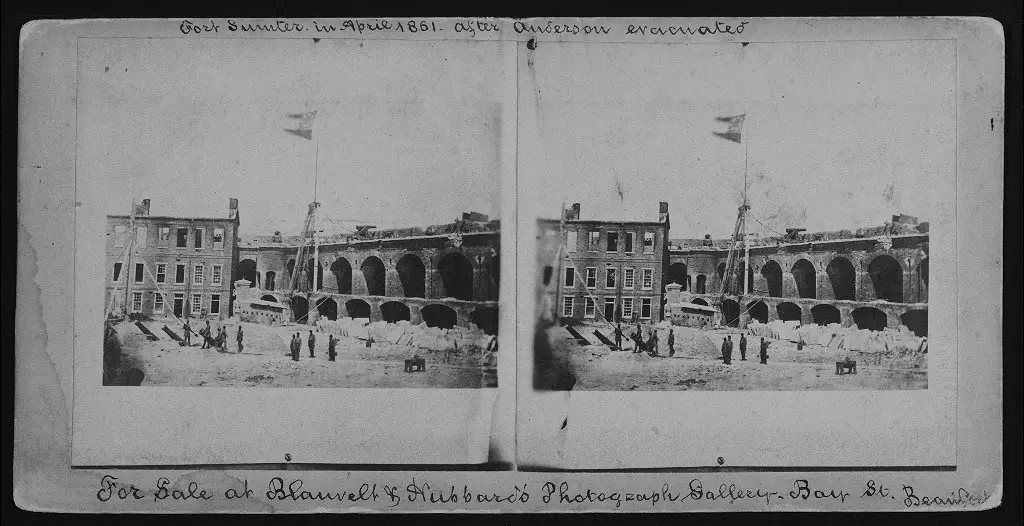

Early on Saturday morning all of our batteries reopened upon Fort Sumter, which responded vigorously for a time, directing its fire specially against Fort Moultrie. About 8 o'clock a.m. smoke was seen issuing from the quarters of Fort Sumter. Upon this the fire of our batteries was increased, as a matter of course, for the purpose of bringing the enemy to terms as speedily as possibly, inasmuch as his flag was still floating defiantly above him. Fort Sumter continued to fire from time to time, but at long and irregular intervals, amid the dense smoke, flying shot, and bursting shells. Our brave troops, carried away by their natural generous impulses, mounted the different batteries, and at every discharge from the fort cheered the garrison for its pluck and gallantry, and hooted the fleet lying inactive just outside the bar.

About 1.30 p.m., it being reported to me that the flag was down (it afterwards appeared that the flag-staff had been shot away), and the conflagation from the large volume of smoke being apparently on the increase, I sent three of my aides with a message to Major Anderson to the effect that seeing his flag no longer flying, his quarters in flames, and supposing him to be in distress, I desired to offer him any assistance he might stand in need of. Before my aides reached the fort the United States flag was displayed on the parapet, but remained there only a short time, when it was hauled down and a white flag substituted in its place. When the United States flag first disappeared the firing from our batteries almost entirely ceased, but reopened with increased vigor when it reappeared on the parapet, and was continued until the white flag was raised, when it ceased entirely. Upon the arrival of my aides at Fort Sumter they delivered their message to Major Anderson, who replied that he thanked me for my offer, but desired no assistance.

Just previous to their arrival Colonel Wigfall, one of my aides, who had been detached for special duty on Morris Island; had, by order of Brigadier-General Simons, crossed over to Fort Sumter from Cummings Point in an open boat, with private Gourdin Young, amidst a heavy fire of shot and shell, for the purpose of ascertaining from Major Anderson whether his intention was to surrender, his flag being down and his quarters in flames. On reaching the fort the colonel had an interview with Major Anderson, the result of which was that Major Anderson understood him as offering the same conditions on the part of General Beauregard as had been tendered him on the 11th instant, while Colonel Wigfall's impression was that Major Anderson unconditionally surrendered, trusting to the generosity of General Beauregard to offer such terms as would be honorable and acceptable to both parties. Meanwhile, before these circumstances were reported to me, and in fact soon after the aides whom I had dispatched with the offer of assistance had set out on their mission, hearing that a white flag was flying over the fort, I sent Major Jones, the chief of my staff, and some other aides, with substantially the same propositions I had submitted to Major Anderson on the 11th instant, with the exception of the privilege of saluting his flag. The Major (Anderson) replied, “it would be exceedingly gratifying to him, as well as to his command, to be permitted to salute their flag, having so gallantly defended the fort under such trying circumstances, and hoped that General Beauregard would not refuse it, as such a privilege was not unusual.” He further said he “would not urge the point, but would prefer to refer the matter again to me.” The point was, therefore, left open until the matter was submitted to me.

Previous to the return of Major Jones I sent a fire engine, under Mr. M. H. Nathan, chief of the fire department, and Surgeon-General Gibbes, of South Carolina with several of my aides, to offer further assistance to the garrison at Fort Sumter, which was declined. I very cheerfully agreed to allow the salute, as an honorable testimony to the gallantry and fortitude with which Major Anderson and his command had defended their post, and I informed Major Anderson of my decision about 7½ o'clock, through Major Jones, my chief of staff.

The arrangements being completed Major Anderson embarked with his command on the transport prepared to convey him to the United States fleet lying outside the bar, and our troops immediately garrisoned the fort, and before sunset the flag of the Confederate States floated over the ramparts of Fort Sumter.

I commend in the highest terms the gallantry of every one under my command, and it is with diffidence that I will mention any corps or names for fear of doing injustice to those not mentioned, for where all have done their duty well it is difficult to discriminate. Although the troops out of the batteries bearing on Fort Sumter were not so fortunate as their comrades working the guns and mortars, still their services were equally as valuable and as commendable, for they were on their arms at the channel batteries, and at their posts and bivouacs, and exposed to severe weather, and constant watchfulness, expecting every moment and ready to repel re-enforcements from the powerful fleet off the bar, and to all the troops under my command I award much praise for their gallantry, and the cheerfulness with which they met the duties required of them. I feel much indebted to Generals R. G. M. Dunovant and James Simons and their staffs, especially Majors Evans and De Saussure, South Carolina Army, commanding on Sullivan's and Morris' Islands, for their valuable and gallant services, and the discretion they displayed in executing the duties devolving on their responsible positions. Of Lieut. Colonel R. S. Ripley, First Artillery Battalion, commandant of batteries on Sullivan's Island, I cannot speak too highly, and join with General Dunovant, his immediate commander since January last, in commending in the highest terms his sagacity, experience, and unflagging zeal. I would also mention in the highest terms of praise Captains Calhoun and Hallonquist, assistant commandants of batteries to Colonel Ripley; and the following commanders of batteries on Sullivan's Island: Capt. J. R. Hamilton, commanding the floating battery and Dahlgren gun; Captains Butler, South Carolina Army, and Bruns, aide-de-camp to General Dunovant, and Lieutenants Wagner, Rhett, Yates, Valentine, and Parker. his immediate commander since January last, in commending in the highest terms his sagacity, experience, and unflagging zeal. I would also mention in the highest terms of praise Captains Calhoun and Hallonquist, assistant commandants of batteries to Colonel Ripley; and the following commanders of batteries on Sullivan's Island: Capt. J. R. Hamilton, commanding the floating battery and Dahlgren gun; Captains Butler, South Carolina Army, and Bruns, aide-de-camp to General Dunovant, and Lieutenants Wagner, Rhett, Yates, Valentine, and Parker.

To Lieut. Colonel W. G. De Saussure, Second Artillery Battalion, commandant of batteries on Morris island, too much praise cannot be given. He displayed the most untiring energy, and his judicious arrangements and the good management of his batteries contributed much to the reduction of Fort Sumter. To Major Stevens, of the Citadel Academy, in charge of the Cummings Point batteries, I feel much indebted for his valuable and scientific assistance, and the efficient working of the batteries under his immediate charge. The Cummings Point batteries (iron--42 pounder and mortar) were manned by the Palmetto Guards, Captain Cuthbert, and I take pleasure in expressing my admiration of the service of the gallant captain and his distinguished company during the action.

I would also mention in terms of praise the following commanders of batteries at the point, viz.: Lieutenants Armstrong, of the Citadel Academy and Brownfield, of the Palmetto Guards; also Captain Thomas, of the Citadel Academy, who had charge of the rifled cannon, and had the honor of using this valuable weapon - a gift of one of South Carolina's distant sons to his native State - with peculiar effect. Capt. J. G. King, with his company, the Marion Artillery, commanded the mortar battery in rear of the Cummings Point batteries, and the accuracy of his shell-practice was the theme of general admiration. Capt. George S. James, commanding at Fort Johnson, had the honor of firing the first shell at Fort Sumter, and his conduct and that of those under him was commendable during the action. Captain Martin, South Carolina Army, commanded the Mount Pleasant mortar battery, and with his assistants did good service. For a more detailed account of the gallantry of officers and men, and of the various incidents of the attack on Fort Sumter, I would respectfully invite your attention to the copies of the reports of the different officers under my command, herewith inclosed.

I cannot close my report without reference to the following gentlemen: To his excellency Governor Pickens and staff, especially Colonels Lamar and Dearing, who were so active and efficient in the construction of the channel batteries; Colonels Lucas and Moore for assistance on various occasions, and Colonel Duryea and Mr. Nathan (chief of the fire department) for their gallant assistance in putting out the fire at Fort Sumter when the magazine of the latter was imminent danger of explosion; General Jamison, Secretary of War, and General S. R. Gist, adjutant-general, for their valuable assistance in obtaining and dispatching the troops for the attack on Fort Sumter and defense of the batteries; Quartermaster's and Commissary Departments, Colonel Hatch and Colonel Walker, and the ordnance board, especially Colonel Manigault, Chief of Ordnance, whose zeal and activity were untiring: The Medical Department, whose preparations had been judiciously and amply made, but which a kind Providence rendered unnecessary; the Engineers, Majors Whiting and Gwynn, Captains Trapier and Lee, and Lieutenants McCrady, Earle, and Gregorie, on whom too much praise cannot be bestowed for their untiring zeal, energy, and gallantry, and to whose labors is greatly due the unprecedented example of taking such an important work after thirty-three hours' firing without having to report the loss of a single life, and but four slightly wounded. From Major W. H. C. Whiting I derived also much assistance, not only as an engineer, in selecting the sites and laying out the channel batteries on Morris Island, but as acting assistant adjutant and inspector general in arranging and stationing the troops on said island. To the naval department, especially Captain Hartstene, one of my volunteer aides, who was perfectly indefatigable in guarding the entrance into the harbor, and in transmitting my orders; Lieut. T. B. Huger, who was also of much service, first as respecting ordnance officer of batteries, then in charge of the batteries on the south end of Morris Island; Lieutenant Warley, who commanded the Dahlgren channel battery; also the school-ship, which was kindly offered by the board of directors, and was of much service; Lieutenant Rutledge, who was acting inspector-general of ordnance of all the batteries, in which capacity, assisted by Lieutenant Williams, C. S. A., on Morris Island, he was of much service in organizing and distributing the ammunition; Captains Childs and Jones, assistant commandant of batteries; to Lieutenant-Colonel De Saussure, Captains Winder and Allston, acting assistant adjutant and inspector general to General Simons' brigade; Captain Manigault, of my staff, attached on General Simons' staff, who did efficient and gallant services on Morris Island during the fight; Prof. Lewis R. Gibbes, of Charleston College, and his aides, for their valuable services in operating the Drummond lights established at the extensions of Sullivan's and Morris Islands. The venerable and gallant Edmund Ruffin, of Virginia, was at the Iron battery, and fired many guns, undergoing every fatigue and sharing the hardships at the battery with the youngest of the Palmettoes. To my regular staff, Major Jones, C. S. A.; Captains Lee and Ferguson, South Carolina Army, and Lieutenant Legaré, South Carolina Army, and volunteer staff, Messrs. Chisolm, Wigfall, Chesnut, Manning, Miles, Gonzales, and Pryor, I am much indebted for their indefatigable and valuable assistance night and day during the attack on Fort Sumter, transmitting in open boats my orders when called upon with alacrity and cheerfulness to the different batteries amidst falling balls and bursting shells, Captain Wigfall being the first in Sumter to receive the surrender.

I am, sir, very respectfully, your obedient servant,

G. T. BEAUREGARD,

Brigadier-General, Commanding. |