| Read all the Civil War Sesquicentennial articles | Comments and Questions to the Author |

The War In The East July 1862

Union Rear Guard at White Oak Swamp

I

McClellan Flees To Harrison's Landing

The battle of Malvern Hill, on July 1, 1862, began around 3:00 p.m. and went on until darkness brought an end to it. Late in the struggle it appeared for a moment that the rebel attacks on McClellan's center were about to break through, but Sumner, whose corps was formed on the right flank of McClellan's line, detached two brigades which arrived in time to patch the hole in the center and stabilize the front.

Malvern Hill

The

result of the battle was a defeat for Lee's army. His divisions, exhausted and

diminished by six days marching and fighting, had been led by their officers to

the assault of formidable positions without order or unity of action, suffering

enormous casualties out of all proportion to those McClellan's soldiers

received. Lee had thrown his forces at McClellan's army again and again and

again, gambling that he could force its capitulation. But the gamble failed

and, for the moment, his army was in shambles. The Confederate offensive,

beginning at Beaver Dam Creek and ending at Malvern Hill, had resulted in the

capture of fifty pieces of artillery, many taken at the point of the bayonet,

many wagons, thousands of rifles, and accoutrements of every description,

provisions, tents, ammunition, together with six thousand prisoners, and among

them several generals. None of this, though, was sufficient to justify the huge

loss in human resource the rebels suffered. Only the fact that the effort had

broken the siege of Richmond justified it. McClellan had been violently

prevented from solidifying the strength of his position on the right bank of

the Chickahominy, forced to make a perilous retreat across difficult terrain to

seek a new base of operations at a further distance from Richmond. Yet,

McClellan had redeemed the defeat at Gaines Mill with a victory at Malvern Hill

and had only to take advantage of it and his fame as a great general would have

been assured. But he failed to do so, missing the chance to snatch success from

the teeth of defeat.

The

result of the battle was a defeat for Lee's army. His divisions, exhausted and

diminished by six days marching and fighting, had been led by their officers to

the assault of formidable positions without order or unity of action, suffering

enormous casualties out of all proportion to those McClellan's soldiers

received. Lee had thrown his forces at McClellan's army again and again and

again, gambling that he could force its capitulation. But the gamble failed

and, for the moment, his army was in shambles. The Confederate offensive,

beginning at Beaver Dam Creek and ending at Malvern Hill, had resulted in the

capture of fifty pieces of artillery, many taken at the point of the bayonet,

many wagons, thousands of rifles, and accoutrements of every description,

provisions, tents, ammunition, together with six thousand prisoners, and among

them several generals. None of this, though, was sufficient to justify the huge

loss in human resource the rebels suffered. Only the fact that the effort had

broken the siege of Richmond justified it. McClellan had been violently

prevented from solidifying the strength of his position on the right bank of

the Chickahominy, forced to make a perilous retreat across difficult terrain to

seek a new base of operations at a further distance from Richmond. Yet,

McClellan had redeemed the defeat at Gaines Mill with a victory at Malvern Hill

and had only to take advantage of it and his fame as a great general would have

been assured. But he failed to do so, missing the chance to snatch success from

the teeth of defeat.

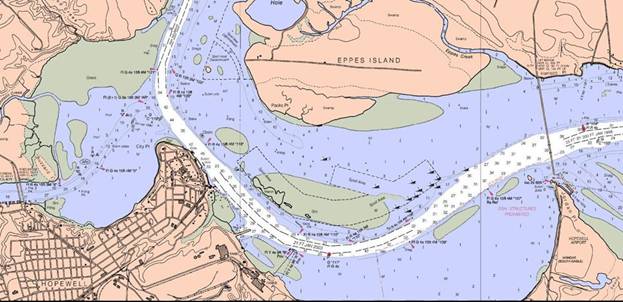

Even before his army was concentrated at Malvern Hill, McClellan had decided not to make it the starting point of his renewed advance on Richmond. According to the Comté de Paris, in his History of the Civil War in America, published in 1867, McClellan "was compelled by the configuration of the course of James River to leave Haxall's Landing" as base of supply and take his army further down the river to Harrison's Landing. "In fact," the Comté wrote, "the James River becomes so narrow above its confluence with the Appomattox at City Point, that vessels going up to Haxall's would have been constantly exposed to the fire of rebel batteries erected on the right bank."

But the objective evidence does not support the Comté's assessment, nor does it sustain McClellan's excuses which he first related in his official report, filed in 1864:

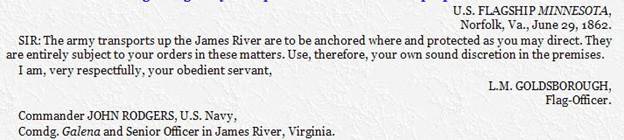

"I extended my examination of the country as far as Haxall's, looking at all the approaches to Malvern. . . I returned from Malvern to Haxall's and went on board Captain Rodger's gun-boat lying near, to confer with him in reference to the condition of our supply vessels, and the state of things on the river.

It was his opinion that it would be necessary for the army to fall back to a position below City Point, as the channel there was so near the southern shore that it would not be possible to bring up the transports, should the enemy occupy It (italics added). Harrison's Landing was, in his opinion, the nearest suitable point.

Although the result of the battle of Malvern was a complete victory, it was nevertheless necessary to fall back still further, in order to reach a point where our supplies could be brought to us with certainty. As before stated, in the opinion of Captain Rodgers, commanding the gun-boat flotilla, this could only be done below City Point."

It is here that history judges George B. McClellan correctly: He will always be remembered as the general that organized the Army of the Potomac into the largest army ever assembled in America up to that time, but failed miserably to extend its range in offensive operations to its full capability. Or did he?

At Malvern Hill, McClellan had the chance to profit immensely from his retreat from the Chickahominy; in fact, he had the chance to improve upon the position he relinquished on the Chickahominy by establishing his base of operations against Richmond at Malvern Hill, using James River to Haxell's Landing as his line of communication with Hampton Road. His excuse for failing to redeem himself, by advancing his army from Malvern, is that the commander of the Naval gun-boat flotilla, John Rodgers, opined that steam transport vessels could not reach Haxell's, if the enemy occupied City Point; the idea being that, in that event, the rebels' guns could prevent the vessels from passing up the James.

The James River Channel Between City Point and Haxell's

James River Channel depths in Front of City Point

James River Channel In Front Of Harrison's Landing

|

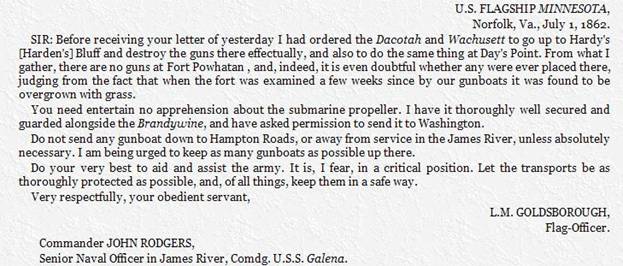

Commander Rodgers had accurately reported to McClellan the fact that the river channel swings close to City Point and Rodgers did, in fact, report to his superior, Commodore Goldsborough, his concern about steam vessels coming under attack at City Point, but George McClellan was in command of an army, the mission of which was to capture Richmond, and this fact ought to have compelled him to hold on to Malvern Hill and take measures to secure his line of communication to that point.

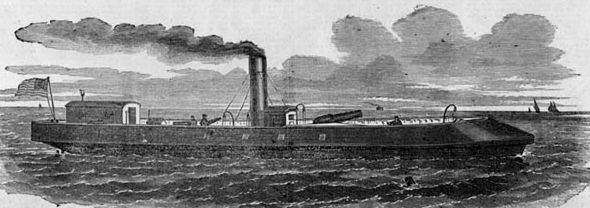

First, McClellan knew that Rodgers was in command of a flotilla of gun-boats and mortar boats that had already steamed successfully up James River to Drewry's Bluff, coming within eight miles of Richmond. Rodgers's flotilla composed of the Galena, Aroostook, Port Royal, Monitor, Naugatuck, and Jacob Bell had had no problem dealing with enemy fire at City Point, nor with enemy fire from the right bank of the river as it steamed through the narrowing river and through the bends and up to Drewry's Bluff. There, the Confederates had established a substantial array of artillery on a bluff on the right bank, had placed a chain across the river, and had sunk vessels loaded with stones in the channel. Rodgers brought the 11-inch Dalgren rifles and the 100 pounder Parrott guns of his flotilla to bear on the Confederate position and a great gun battle ensued, with Rodgers finally giving way after the Galena had been riddled by forty-eight strikes. |

Galena

Aroostook

Naugatuck

Rodgers's Flotilla In Action

Drewry's Bluff Fortifications

Rodgers then steamed back down the river to Tar Bay―the fat bulge in the river shown on the maps—and steamed up the Appomattox River in an effort to reach the railroad bridge at Petersburg.

Commander Rodgers's Communications with Goldsborough

On June 27, Rodgers used the Galena to bombard City Point, while troops went ashore in boats and destroyed buildings and a Confederate depot. In the course of this action, it became clear that there were no Confederate artillery, no fortifications, and no troops of much account present at this place. On the same day this action took place, McClellan came abroad the Galena to conduct what he calls his reconnaissance. So, we know that McClellan had four days to make up his mind what his army was to do after it reached Malvern Hill and repulsed the enemy's last attacks. The historians and civil war writers criticize McClellan for leaving his army on its retreat from the Chickahominy and going on board the Galena―some go so far as to label his action a "dereliction of duty"—but this misses the point. McClellan had plenty of time to reconnoiter Tar Bay and City Point and plan how to protect the channel for the passage of transports past it and up to Haxell's Landing. Indeed, it seems most probable that it was he who ordered the troop landing at City Point on June 27th. (I leave it to the viewer to search the Rebellion Record for confirmation of this.)

Later, when Lincoln arrived at Harrison's Landing, on July 8, and met with McClellan, McClellan broached the idea of crossing the army over the James, occupy City Point and move up the Appomattox to capture Petersburg thereby choking off Richmond's line of communication with the Confederate heartland. If he thought such a movement feasible then, he certainly must have thought it possible, on June 27-30, to quickly land troops at City Point to secure the place and, thus, secure the passage of the river for his transports.

City Point in 1864

City Point, 1864

Sitting in a cabin on board the Galena, pouring over his maps, McClellan must have spent considerable time during that four day period, calculating how his army might be advanced up the James's left bank, to again come within contact of the Richmond defenses. Clearly, the Union's unchallengeable command of the river with gun-boats and war ships, at least as far as Drewry's Bluff, meant that, as the army moved up the left bank, the navy's big guns would be throwing shells four and five miles inland, protecting the army's right flank as it moved. McClellan in his report of Malvern Hill praised the Navy's ability to support him in this fashion and so he had to have known what worked for him at Malvern would probably work for him between Malvern and Richmond.

From Malvern Hill To The Richmond Suburbs

McClellan also would have recognized immediately the necessity of constructing a line of fortifications to protect his right flank and keep his base at Malvern Hill secure. No doubt, he expected that full scale battles would erupt in the terrain between the Richmond defenses and Malvern Hill, along the length of the River Road as his advance progressed, but the offensive burden of these battles would be on Lee, not on him. Yet McClellan shrank from the task of advancing his army eleven miles up the River Road to the Richmond suburbs. Why? Because, as he had on the Chickahominy, given the size of his army, he thought the task of protecting his right flank to be impossible.

McClellan's Situation on the Chickahominy

In other words, McClellan found himself in exactly the same tactical situation he had been in, on the Chickahominy: his army had to do two things simultaneously—it had to defend its communications from the enemy's right flank attacks while it advanced to attack the Richmond fortifications. The historians and civil war writers have uniformly ignored the true objective significance of this predicament, in evaluating George McClellan's professional performance as a soldier. To accomplish both operations simultaneously, any general―Grant included—standing in McClellan's shoes, would have required more men.

Grant's Lines At Petersburg, 1864

From a purely analytical point of view, the objective record of the Civil War demonstrates that no Union general, Grant included, successfully performed both operations simultaneously. As the record shows conclusively, Grant arrived in June 1864, at exactly the same spot that McClellan was in, in June 1862 when Lee attacked his right flank at Beaver Dam Creek, and Grant, after losing 10,000 men in ten minutes at Cold Harbor, moved on to the James; and at the James, instead of advancing toward Richmond from Malvern Hill, Grant crossed the river, occupied City Point and began digging his way toward the three railroads that fed Richmond through Petersburg with supplies. Grant spent nine months digging due south, parallel to Petersburg, cutting the railroads, one by one; and while he made some attacks on Lee's lines in the process, they all failed.

As his army was marching away from Malvern Hill toward Harrison's Landing, McClellan telegrammed Lincoln, asking for fifty thousand troops as reinforcements. Lincoln continued to pretend this was impossible, replying to McClellan with this:

When you ask for 50,000 men to be promptly sent you, you surely labor under some gross mistake of fact. All of Frémont's in the valley, all of Banks's, all of McDowell's not with you, and all in Washington, taken together do not exceed, if they reach, 60,000. Thus the idea of sending you 50,000 is simply absurd. Save the army and I will strengthen it for the offensive again as fast as I can. The Governors of eighteen States offer me a new levy of 300,000 which I accept.

Setting

aside his inability to do math—he had in his hands at least 80,000, if not

100,000, men―Lincoln was still clinging to the mind-set in which he refused

to put all his eggs in one basket. And, of course, Lincoln had already decided

to put Frémont's, Banks's, and McDowell's divisions into one army to be

commanded by John Pope, who he had called to Washington and who had arrived

there, just as Lee was attacking McClellan's flank at Beaver Dam Creek; and, of

course, McClellan knew this at the time he sent the telegram. Was there ever,

before or since, a more dysfunctional relationship between an American

president and his generals? The relationship between MacArthur and Truman pales

in comparison.

Setting

aside his inability to do math—he had in his hands at least 80,000, if not

100,000, men―Lincoln was still clinging to the mind-set in which he refused

to put all his eggs in one basket. And, of course, Lincoln had already decided

to put Frémont's, Banks's, and McDowell's divisions into one army to be

commanded by John Pope, who he had called to Washington and who had arrived

there, just as Lee was attacking McClellan's flank at Beaver Dam Creek; and, of

course, McClellan knew this at the time he sent the telegram. Was there ever,

before or since, a more dysfunctional relationship between an American

president and his generals? The relationship between MacArthur and Truman pales

in comparison.

Probably, too, at the time Lincoln replied to Mac's telegram, he had already decided to call Henry Halleck from the West. For, his agent, Rhode Island Governor Sprague, had left Washington on July 6 with a letter to be delivered to Halleck, this the same day Lincoln left Washington to travel to meet McClellan at Harrison's Landing on July 8.

|

Westover, at Harrison's Landing

McClellan, in both his 1864 official report and in his posthumously published biography, does not tell us anything about what was said between himself and Lincoln during Lincoln's visit to Harrison's Landing. For Lincoln's part, we have only the 1885 publication of his employees, Hay and Nicolay, who wrote this:

The President reached Harrison's Landing on the 8th of July, and while there conferred freely, not only with General McClellan, but with many of the more prominent officers in command. With the exception of General McClellan, not one believed the enemy was then threatening his position. Sumner thought they had retired, much damaged (true); Keyes that they had withdrawn to go towards Washington (not true); Porter that they dared not attack (true); Heintzelman and Franklin thought they had retired (true); Franklin and Keyes favored the withdrawal of the army from the James; the rest opposed it.

Upon his return to Washington, on July 11, Lincoln penned this order to Halleck:

Ordered, That Major-General Henry W. Halleck be assigned to command the whole land forces of the United States, as general-in-chief, and that he repair to the capital as soon as he can with safety to the positions and operations within the department in his charge.

Why Lincoln did not simply make Halleck take command of both Pope's new army and McClellan's, as Halleck had done with Buell's, Grant's, and Pope's, after Shiloh, escapes understanding completely. One possible explanation is, that, though Grant held the status as second in command to Halleck, once Halleck left the Department, either he or Lincoln or both did not want Grant to assume command of the Department. Had Grant assumed department command, it would have meant that Buell's army, as well as Pope's―now commanded by Rosecrans—would be under Grant's operational control. Clearly, Grant did not have the confidence of either Halleck or Lincoln at this time, and so Lincoln made Halleck "General-in-Chief" in order that Halleck would continue to supervise Grant and control the movements of Buell and Rosecrans, as well as Grant, directly. What other explanation for Lincoln's maneuver is there? Halleck did not ask to be made General-in-Chief; in fact, he asked to be in command of all troops in the East only.

Even if Lincoln expected, nonetheless, that Halleck, as he had on the advance to Corinth, would take field command of both Pope's assembling army on the Manassas Plain and McClellan's on James River, Halleck obviously demurred. Unlike the situation in the West, in April 1862, Halleck had no easy way to concentrate the two armies together. In the West, Buell's army had arrived in the nick of time to save Grant's army from annihilation at Shiloh and thus the two armies were together when Halleck arrived to command the advance to Corinth; at the same time, Missouri having been swept clean of organized rebel forces, John Pope's army of the Mississippi also arrived at Shiloh to join in the advance. But, when Halleck arrived in the East, in July 1862, he found two Union armies separated by ninety miles of terrain with General Lee's army in between and had to somehow bring them together before he could duplicate what he had done at Corinth.

There were only three ways in which Halleck could have brought the two armies together: either Pope's army had to march south from the Rappahannock to Richmond while McClellan marched north, or Pope's army had to reach Harrison's Landing by steam vessels; or McClellan's army had to reach the Manassas Plain by steam vessels to Acquia Creek and Alexandria. Originally, Lincoln had paid lip service, at least, to the idea of Pope marching south to join McClellan, but that was at a time when McClellan had his army positioned on the Chickahominy; with McClellan's army having dropped away from there to the James River, Lincoln, it can reasonably be assumed, would not allow Pope to march overland. This left the alternative that Pope go to McClellan by steam vessels; but, again, Lincoln clearly would not allow this to happen.

Why? Because Lincoln's mind on this point was like a bar of iron. He knew he had a bottomless pool of men to throw into the fire, and that it was certain the war was being won decisively in the West: making it only a matter of time before the Western armies penetrated the heartland of the Confederacy. The Western armies could operate together, without interference from Washington, because they did not have to defend the Union capital, but the Eastern armies could not operate together because Lincoln would not take any chance that the enemy might reach Washington. The only way, in Lincoln's mind, the war might be lost was if Britain broke the Union blockade. For Lincoln, taking no chance, meant that both a force manning the fortifications around Washington and a force in the field in front of the forts were required. This was Lincoln's intractable mind-set and it explains his resolute refusal to strengthen McClellan's army to the point it could both defend its communications and attack the Richmond defenses. At some point―probably when Stonewall Jackson over ran the lower Shenandoah Valley for a moment—Lincoln must have realized how his policy made McClellan's mission to capture Richmond impossible, and this explains why, in June, he had wired Mac that the job should be given up and Mac should bring the army back.

|

II

General Lee Sends Jackson to the Rapidan

The contrast in personal relationship between President Davis and General Lee and that of McClellan and Lincoln is very great, and accounts, in large measure, for the success of General Lee's effort to transfer his army from James River to the Potomac. The measure of respect these two men shared is evident in the contrast between their correspondence and that of Lincoln and McClellan. For example, President Davis wrote these letters to General Lee, the first replying to the latter's message explaining the impossibility of attacking McClellan in his position at Harrison's Landing:

Richmond, July 4, 1862

R.E. Lee, General:

I fully concur with you as to the impropriety of exposing our brave and battle-thinned troops to the fire of the gunboats while attacking a force numerically superior and having the advantage of so strong a position as that held by the enemy. If there should be anything which you think would be more certainly executed by my personal attention you must not hesitate to ask for it. I renew my caution to you against personal exposure either in battle or reconnaissance. It is a duty to the cause we serve for the sake of which I reiterate the warning.

Very respectfully and truly, your friend,

JEFFERSON DAVIS

Richmond, July 5, 1862

General R.E. Lee, commanding:

The entire confidence reposed in you would suffice to secure my sanction to your view of the propriety of withdrawing to a better position for your troops. The enemy commands the water up to our batteries, and thus necessitates on your part a retrograde movement. Where you go, you are better able to judge than myself, and I would not be regarded as interfering with the free exercise of your discretion.

Very respectfully and truly, yours,

JEFFERSON DAVIS

Here is one of General Lee's letters to President Davis:

Hdqrs. Army of Northern Virginia

His Excellency President Davis,

Mr. President: I conclude that the enemy has been reinforced and intends to make a lodgment on the James River as a base for further operations. The great obstacle to operations here is the presence of the enemy's gunboats, which protect our approaches to him and would prevent us from reaping any of the fruits of victory and expose our men to great destruction. This consideration induces the opinion that it may be better to retire the army near Richmond, where it can be better refreshed and strengthened, and be prepared for a renewal of the contest, which must take place at some quarter soon.

I have the honor to be, your obedient servant,

R.E. Lee, General

July 6, 1862

In accordance with the views expressed, General Lee began moving the main body of his army―now organized as the commands of Jackson and Longstreet—back to the suburbs of Richmond on July 8th, the day Lincoln arrived at Harrison's Landing. At this time, General Lee shed from his army several major-generals and other officers who he thought had underperformed during the battles of the Seven Days, and he dealt with the necessity of stifling the egos of those who remained. On July 12, for example, A.P. Hill, who went into the Seven Days with the largest division in the army, found himself under Longstreet's command and asked to be relieved. Longstreet did not object, but Lee tabled it. Hill pressed the matter, however, having become embroiled with Longstreet over a perceived slight he thought he received at the hands of Longstreet's staff. In the course of the dispute, Longstreet ordered Hill to be arrested and Lee promptly ordered Hill, with his light division, transferred from Longstreet's to Jackson's command.

At about this same time, General Lee directed Stonewall Jackson, with three divisions―his own, Richard Ewell's and, coming a little later, A.P. Hill's—to march north toward Culpeper County, where reports suggested John Pope's army was concentrating. Reduced by sickness and the casualties of the Seven Days, these three divisions amounted to little more than 24,000 men. On July 16th, Jackson's leading division reached Gordonsville, just as Pope's cavalry was approaching the place. On July 26th, as Henry Halleck was arriving at Harrison's Landing, Lee sent this message to Jackson:

I will send you A.P. Hill's division. I want Pope suppressed. Cache your troops as much as possible till you can strike a blow, and be prepared to return to me when done, if necessary. I will endeavor to keep General McClellan quit till it is over, if rapidly executed.

At the end of July, A.P. Hill's division arrived at Gordonville just as Pope's army―Sigel's, Banks's, and McDowell's corps (six divisions 47,000 strong)—were moving south to the Rapidan River and Pope's cavalry drove Jackson's out of Orange Courthouse and Union scouting parties penetrated to within a few miles of Jackson's headquarters at Gordonsville. And General Lee began seriously to consider how to take advantage of Lincoln's dilemma: two Union armies separated by many miles. On July 28, Lee wrote the Confederate Secretary of war:

"I have ordered our big guns to be moved to endeavor to cut off McClellan's communications with the river. (McClellan by this time had made a show of moving a force back to Malvern Hill.) I know of no heavier blow that could be dealt McClellan's army than to cut off his communication. It would oblige him to retire at least to the broad part of the river. The attempt, if only partially successful, will anchor him in his present position from which he would not dare to advance, so that I can reinforce Jackson without hazard to Richmond, and thus enable him to drive if not destroy the miscreant Pope."

Within the space of thirty days, General Lee would not only do that, though substantially outnumbered by Pope, but he would manevuer Lincoln's other army―almost three times the size of his—into the most bloodiest battle the war would ever see, and gain for his army the opportunity to rehabilitate itself in the Shenandoah Valley unmolested by the enemy for six weeks, building its strength up again and ready to block the Union's efforts to get beyond the Rappahannock.

Joe Ryan

Joe Ryan

The War In The East

| Read all the Civil War Sesquicentennial articles | Comments and Questions to the Author |

|

Joe Ryan Original Works @ AmericanCivilWar.com Joe Ryan Video Battlewalks |

|

| About the author: Joe Ryan is a Los Angeles trial lawyer who has traveled the route of the Army of Northern Virginia, from Richmond to Gettysburg, several times. |

||

Battle of Gettysburg

General Robert E. Lee

General JEB Stuart

General Jubal Early

Confederate Commanders

General Joseph Hooker

Union Generals

American Civil War Exhibits

State Battle Maps

Civil War Timeline

Women in the Civil War