| Read all the Civil War Sesquicentennial articles | Comments and Questions to the Author |

What Happened In July 1862 ©

| The War in the East July 1862 | |

| The War in the West July 1862 |

In The Senate Of The United States Congress

July 7, 1862

Provisional Governments

The Senate, as Committee of the Whole, proceeded to consider the bill (S.No. 200) to establish provisional governments in certain cases. The bill proposes to give authority wherever, within the territorial limits of the United States, the constitutional authority of the United States is or may be resisted by arms during the present rebellion, to the president of the United States in order, to establish a provisional government.

The executive power of every government so established is to be exercised by a Governor, the judicial power by three judges, and the legislative power by a legislature consisting of the governor and the three judges.

The amendment sought to insert into the language of the bill the following limitation on the power of the governor and three judges, "and not interfering with the laws and institutions existing in such State at the time its authorities assumed to array the same against the Government of the United States."

Note: The lauguage of the amendment is an example of the core tension between the senators that threads through all the legislation they are considering during the second session of the Thirty-Seventh Congress. One group, composed of about half the Republicans and all of the Democrats, are still clinging to the illusion that the nature of the war is simply "rebellion"—that is, the Union remains intact, the country intact, with the Federal Government simply suppressing a group of rebellious citizens. Therefore, when, in the process of suppressing the rebellion, the Federal Government sets up "military governments" to execute the laws in a certain area, the military government must enforce the civil law as it exists in that area; i.e., enforce the rights of slaveowners against slaves.

The other group of senators, composed of about half the Republicans―these are the radicals, men like Sumner, Wade, Chandler, Trumbull, and King—are operating with a view toward conquering the South, destroying the slave States' infrastructure and extinquishing the institution of slavery by force of arms. With them the language of the Constitution means nothing. The concept of a republican form of government means nothing. Slowly through the six months of the congressional session, the latter group take command of the majority, in part by changing senate rules of procedure, in part by the assistance of Lincoln who goes with the flow.

Mr. Sumner, of Massachusetts: I cannot consent to that amendment. It seems to me that it is going very far. A government organized by Congress, and appointed by the President, is practically to enforce laws and institutions, some of which are abhorrent to civilization. For example, I have before me a law of North Carolina; it reads: "any free person who shall teach any slave to read shall be deeded guilty of a misdemeanor and shall be imprisoned, fined, or whipped."

Sir, the bare statement of the case is enough. It is impossible to consent to any such thing. In organizing these governments, all we can do is protect life and property, and generally to conduct the machinery of government. We cannot go further, and protect institutions which are an outrage to civilization.

Mr. Harris, of New York: Mr. President, the object of the bill is not to change the legislation of the States. It is to establish a temporary government, to execute the laws and constitution of the rebel States during the interval that may occur between the time when the rebellion shall be suppressed, and when those States shall be able to reorganize themselves and shall be restored to their proper position in the Union. During this time those clothed with authority to govern the State requires some power to legislate, but I should be very unwilling to clothe these officers with power to change the entire body of laws of those States.

Mr. Ten Eych, of New Jersey: I oppose this bill. In my view, States in rebellion, as the southern States now are, are still States of this Union, as much today as they were when they became so by their admission into the Union; and that no act of insurrectionists or rebels can change the legal character or status of these States from that which they were entitled to and enjoyed prior to the commencement of the rebellion; and that to recognize any other doctrine acknowledges at least the power, if not the right, of secession.

Note: The theory of the Union that Mr. Ten Eych expresses, is one repeated frequently by historians in their books, to characterize the war as a "civil war" as opposed to a war "between States." The distinction between the two concepts goes to the core of the debate whether, under the political system the founders framed with the Constitution, a State—let us stick for the moment with an "old" State―could legally "secede" from the Union.

Adopting this theory as your own saddles you with the position that, despite the formal political action of its citizens proclaiming otherwise, the State is still in the Union. And this position forces you, as it does with Mr. Ten Eych, to acknowledge that the Federal Government cannot change the domestic policies of the State. Why? Because as a State presumed to be still in the Union, it is entitled, under the Constitution, to a republican form of government; meaning a government of its choice, not yours.

It is against this very heresy that we are now offering up hundreds of thousands of precious lives. Under our frame of government there can be no such thing as secession. The Union was meant to be perpetual, and if such a thing as secesssion in fact exists, it is because the Federal Government has not sufficient force to compel obedience to its powers.

Note: "The Union was meant to be perpetual." This is one prong of the traditional argument raised to rebut the proposition that, under the Constitution, secession was lawful. In fact, the objective record shows that the framers did not for a moment think the Union, as a political institution, was to be "perpetual" no matter what its members might decide to do with their allegiance to it.

The easy rebuttal to the statement—"The Union was meant to be perpetual"―is to point to the Articles of Confederation, which do indeed unequivally state that the Union formed by the instrument is "perpetual," and then point to the Constitution which, if adopted by nine of the thirteen States confederated, forms a new Union comprised of the nine, with the remaining four out in the cold and on their own. So much for the value of raising "The Union was meant to be perpetual" argument.

In my view the people of a State constitute the State; that the State is not constituted by a mere ideal outline or boundary of territory; for if the territory be devoid of people, it surely cannot be a State.

Note: Here, Mr. Ten Wych has got it right on a key political concept that underlies the law of nations. It is that the people constitute the State. The question then is, under what circumstances can the people change the affiliation of their State with a larger political body? And, to what extent should the people be responsible for the State?

The people then constitute the State; and I hold that if there be one hundred or ten true and loyal Union men in one of these insurrectionary Staes, although all the rest are rebels and deserve destruction, they constitute the State and are entitled to all the blessings and all the immunities of their State governments under the Constitution; nay, more, the Government of the United States, by the Constitution, is bound to protect them in their State governments and to maintain them in a republican form of government. We may establish temporary or local control over these insurrectionary States, as we have already begun to do and are now successfully doing in the State of Tennessee, by the appointment of a military governor (Andrew Johnson), who, armed with the whole power of the United States, puts down rebellion and enforces the laws.

Note: Here you see the fatal flaw in the argument that, in terms of political science, much less of law, the rebel States are still in the Union, in 1862. The people of South Carolina in convention assembled vote unanimously that their State secede from the Union, but, because in one county of the State, when the convention's delegates were elected on a secession platform, ten citizens of South Carolina voted against the platform, ipso facto the State must be deemed still in the Union. The argument is absurd.

This bill provides for a provisional government in a State, as against the State government. It frames and organizes an antagonistic government to the State government which the true and loyal people living in these insurrectionary Staes have the right to have maintained for their protection and benefit. I cannot vote for a bill that would establish such a government, when the Constitution guarantees the loyal people a Republican government. This bill reduces these States to a territorial condition.

Mr. Powell, of Kentucky: I have been taught to believe that there was no liberty save in the supremacy of the laws; and I now ask the senator who introduced this bill to show me the clause in the Constitution that will warrant or authorize its passage. I will say there is no such clause.

Mr. President, in my judgment this bill in every feature of it is unconstitutional. There is no power vested in Congress to declare sovereign States provinces. This bill does that virtually. There is no power in Congress to declare that the people of a State of this Union shall not govern themselves in all matters touching their domestic affairs. I ask my friend from New York what he would do with the clause of the Constitution which says the United States shall guarantee to every State in the Union a republican form of government? A republican form of government is one in which the people shape their own domestic policy in a manner that suits them, so that it is not in contravention of the Constitution of the United States. The people of every State in the Union have a right to govern themselves just as they please, subject to the limitations of the Constitution.

Note: Mr. Powell's statement of the case is as close to the mark as objective lawyers and political scientists can get. It highlights the great truth about the war; the war changed "States" into provinces by stripping from the people of these States their sovereign right to control their domestic policy. In 1862, it was the domestic policy of slavery that caused this political revolution to happen; a "good" thing in itself.

One hundred and fifty years later, the consequence of this revolution puts Kansas, in its effort to outlaw abortion within its borders, on Mr. Powell's side of the case; the same with Arizona and Alabama, in their efforts to close their borders to aliens; and California, and a dozen other states, in their efforts to ignore Federal drug laws; and Oregon, in its effort to ignore Federal law making suicide a crime. (Not to mention the issue of "civil marriage" to include gay couples.)

What does this bill do? It clothes the President with the power to send a Governor and two judges to any State in this Union where rebellion exists, and that they shall become the executive and the law making power for those people. Yes, sir, it clothes the President with the power to send Wendell Phillips, or Lloyd Garrison (or Frederick Douglas) to South Carolina, with power to make laws and execute them on that people in derogation of all their local rights. This is a most astounding heresy, a thing unknown to our system of government.

Note: Note Powell's language: ". . . to any State in this Union where rebellion exists. . ." By the end of the congressional session, and certainly by September 21, 1862, when Lincoln publishes his "Emancipation Proclamation," a majority is coalescing in the Senate around the recognition that the seceded States are, indeed, out of the Union, and the Confederacy is, indeed, a foreign power that must be conquered by the Union's force of arms.

Sir, let me tell the senator from New York that this bill of itself is disunion. It is contended here every day that this Union is a Union of sovereign States. Thirty-four sovereign States, they claim, now compose this Union, the Union as formed by the Constitution. But the Senator now comes with his bill and asks for the passage of a law that absolutely blots out of existence these sovereign States and reduces them to provinces, to a condition worse than provinces. You do all in the name of Union. Under that profession you destroy the Union.

Note: The bill in question is the basis eventually for the Union's military occupation of the South, which lasts for ten years, with army officers serving as military governors. The seceded States are admitted back into the Union only after they ratify the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments to the Constitution which effectively delete from the Constitution the framers' acceptance of the domestic policy of the slave states, as lawful.

Mr. Harris: Here are some of the States that declare they are not in the Union, that they will not be governed in the Union, . We set about as a Government to subdue those States, to suppress the rebellion, and as fast as we succeed in that, we undertake to enforce the Constitution and laws of the United States. With that view, military governors are appointed. They have already been appointed (by Lincoln without any law to authorize it), one in Tennessee and one in North Carolina. Where is the provision in the Constitution that authorizes the appointment of military governors? It is hard to find it. It is only under the provision that I say exists, that these States are governed in the Union.

A military government implies that the provinces governed are conquered provinces. The States where these military Governors are appointed are in some sort prisoners of war, and we hold them as conquered States, as prisoners, and undertake to govern them by the arbitrary government of military law.

Note: A "conquered" State can hardly be characterized simultaneously as a "sovereign" State. See how the two competing concepts the Senators are espousing mesh?

Now, sir, this bill contemplates another step in this process; that after these States shall be conquered, after the rebellion shall be suppressed, after the rebels shall be subdued, then, before these States can be brought back into the Union, before the people of those States thus subdued are ready to reorganize themselves and to come back into the Union as loyal States, the Government of the United States shall provide that they be governed in the manner contemplated by the Constitution.

Note: So Senator Harris recognizes that, by their act of seccession, the Confederate States are out of the Union?

How else to do it? You are compelled to resort to some such expedient as this: they have the machinery, they have a constitution; they have laws; but they will not execute them. The people will not organize a [loyal] State Government. They do not. What are you to do? In my judgment, it is the duty of the Federal Government to see that their own laws are executed until they themselves will voluntarily [read duress] organize themselves into a State Government.

Note: Senator Harris is wandering in the morass and has fallen into a sinkhole. He is admitting that the Federal Government is conquering what were once sovereign "States" and treating them as captured territory to be reorganized into provinces as soon as the people living in the territory can be induced to comply with the new program.

Mr. Cowan, of Pennsylvania: I have sometimes been of opinion that there was danger that we would depart, very materially depart, not only from the great principles which were established by the Revolution, but from the principles which were declared by ourselves at the time we undertook this war to suppress the rebellion.

Note: Of all the senators of the thirty-seventh congress, Mr. Cowan, to my mind, stands at the head of the first flight, a real constitutional lawyer with a firm grasp of the realities who believes completely in the principles the founders relied upon in designing the Union.

Sir, what is a republican form of government? Is it not a government formed by the people by their own free consent? The government of North Carolina, before the rebellion, was a government formed by her people and, recognized by this Government. This Government was bound by the Constitution's guarantee to support republican forms of government, to sustain and support that government. Now, sir, a rebellion takes place. If that rebellion involves the whole people in it, that people, by a fundamental principle of our Constitutiont, have a right to establish such form of government as they choose; and if it had been established to the satisfaction of Congress that the whole people of the State in which the rebellion prevailed had been involved in that rebellion, and were anxious to sever their relationship with the Union, I suppose nobody would have undertaken to put down that rebellion. I suppose no Democrat would have undertaken it. I suppose no Republican would have undertaken it. I suppose no man who understands the theory which underlies our Government would have ever undertaken it.

Note: Mr. Cowan gets to the heart of the matter. He is saying that the "whole" people of an American State have the right to secede their State from the Union and if they did this, then the Federal Government has no constitutional authority to use force to prevent it. Of course, the factual debate then must turn to what is meant, under Cowan's expression of the political theory, by "whole." Senator Harris insists that if one citizen objects to the State's secession, the test of "wholeness" has not been made. How many dissenters does it take, in Senator Cowan's view, to negate the "wholeness" criteria?

Of course, as far as Abraham Lincoln is concerned, Cowan's reliance on abstract principles of law is irrelevant. Lincoln does not care about lawyer arguments, about what is "right" or "wrong" in the abstract. His focus is squarely on the fact that the Union must not allow any foreign State to exist on the American continent, regardless of its origin, or its claimed "right" to exist. The Union, in his mind, must use all its power to suppress the existence of any such State, and that is why the Union is at war with the Confederacy.

What, then, was the theory upon which we inaugurated this war? It was because we decided all the people of the rebellious States were not in favor of this rebellion. It was because we believed it was confined to a few. I had no doubt of it. I have no doubt of it now.

Note: How silly is this? To avoid the framers' theory of government, Mr. Cowan tells us Congress "decided," Congress "believed" that "all the people (of say, South Carolina) were not in favor of this rebellion," only "a few." Sidney Johnston led forty thousand young men to Shiloh where ten thousand, in throwing themselves at Grant's fledging army, were either killed or wounded. On June 26, 1862, General Lee led fifty thousand young men against McClellan's right flank, and then through the Seven Days to Malvern Hill. These young men suffered twenty-five thousand casualties. Behind these young men stood their fathers, mothers, and siblings.

Those, Cowan says, in favor of the rebellion were "confined to a few?" Nonsense. The whole people, in the same fraction of the whole that voted in convention assembled to ratify the Constitution, in 1789, voted in convention assembled, in 1861, to ratify their States' Articles of Secession.

So, by the framers' theory, which Cowan accepts, the rebellious States should have been allowed to walk. But theory ends when a Government's territory is at stake. The Sudan, Syria, Serbia, China, Israel, Britain: do governments care how many citizens in a region are insisting on change of territorial control? Do governments care about abstract notions of law, of political science, of theory? Of course not. If they can hold what they think they own by force, it is in the nature of governments that they will use it against any one, civilians or no, who opposes their control.

We went to war to rescue the many as against the few—to rescue the loyal as against the disloyal. That was the theory; and upon no other theory can this war be justified or the Government be sustained; because no one then suggested conquest, and all denied it.

Note: Lincoln is listening to this, and rejecting it out of hand. He instigated the war, in order to hold the Union together by force. In less than ninety days he will publish his so-called "Emancipation Proclamation" which will announce his policy: If you live within rebellious territory and own slaves they are emancipated because I say so, and your claim you are one of the "many" loyal people being abused by the few will be ignored. The case has finally come down to one of conquest; forget the nonsense about being in the Union under the Constitution. You are a foreign power, pure and simple, and you will not be tolerated on this continent.

In pursuance of our design not to make a conquest, not to subjugate, but to rescue and restore, we invade a particular State, and we put down the rebellion. What is next to be done? Guarantee them a republican form of government. What republican form of government, I ask? The republican form of government which they made for themselves? Unquestionably. What other one? Who dares propose another one? And yet the Senator from Massachsetts would discharge that guarantee by taking it away and substituting one of his own instead. But he says some of the State's laws are atrocious, and are abhorent to the civilized world. Very well, whose business is that, according to our theory? The business of the Senator from Massachusetts, or of the people of South Carolina, who had the right to make them? The question is whether we will stand upon a great truth taught us in the Revolution, whether we will give to the people the government which they established. I thought that right was the very thing which was achieved by the Revolution. In this country it was decided that the people should frabricate for themselves their government. And that is all we can do if we pretend to carry out the doctrines upon which we entered upon the war―namely, that a State could not go out of the Union, and that, therefore, we could not make a conquest of her as if she were out.

What, then, can Congress do? I answer, nothing. But the President, or his generals acting under his direction, after the rebellion is subdued, can preserve order by military rule until the old government resumes its wonted action. This is a military function, requiring military force. This is my view of it.

Mr. Howard, of Michigan: I do not wish to interrupt, but may I ask a question?

Mr. Cowan: Certainly.

Mr. Howard: I wish to ask him what he would do in case it should turn out that the rebel States had no loyal people at all? How is he going to govern them, and how are they going to govern themselves?

Mr. Cowan: Will the honorable Senator allow me to ask him a question? I have stated distinctly that unless we contemplate conquest it is one of the fundamental principles of our theory of government that the people of a State have a right to form their own government; in other words, it is the right of revolution, if they can make it good. Are governments to be perpetual; and if they are not, where is the power to change them, if not in the people?

Note: Mr. Cowan is talking in a circle here. On the one hand he is saying the "whole" people of South Carolina had a right to form their own government, "but on the other he is saying, "if they can make it good."In other words, despite his lip service to theory, he, too, like everybody else in the room, qualifies the principle of the American Revolution by reference to the force of arms. "You can be free of us, if you can prevent us from invading and devastating your homes." That is what all the Senators, one way or another, are saying.

Mr. Howard: Does the Senator wish an answer?

Mr. Cowan: Certainly I do.

Mr. Howard: The United States of America in Congress assembled has the right to make that government and enforce it.

Mr. Sumner: Beyond all question.

Mr. Cowan: Then you proceed against them precisely as though you proceeded against a foreign State in case of conquest, but that is not under the Constitution.

Note: This one sentence captures in a nutshell the reality of the American Civil War; in what high school, or college, is the reality of this taught?

And this doctrine of the right of conquest is precisely the doctrine which was held by the Parliament and the King of Great Britain in our Revolution. It is the doctrine which has been held by all tyrannies from the time the world began. If this Government becomes a tyranny, how is it to be changed, unless there is some such right of revolution somewhere?

Note: There it is, the objective truth of history American historians, by and large, cannot bring themselves to teach their students. How is it to be changed, if the right of revolution is not recognized, as a right? How is Syria's Government to change? How is China's? How is ours? Without it?

Mr. Carlile, of "Virginia:" The Senator from Michigan puts to the Senator from Pennslyvania a question what will you do if there are no loyal people in any of these rebellious States. If there are no loyal people left in the State after the suppression of the rebellion, I take it there will be no people to govern. You will have exterminated them all and it will be a vast wilderness to be repeopled.

Mr. Howard: I ask my friend from Virginia whether he expects the rebels are to die in the last ditch?

Mr. Carlile: I have proceeded on the theory that there will be loyal people left, this is the only theory we can go on in the name of the United States and wage this war. If it is waged under any other theory it can only be justified upon the ground that rebellion has dissolved the Union, and that this is a war on the part of the non-seceded States against the seceded States for the purpose of compelling them to remain in the Union.

The Senator talks of conquering States. Where does he derive the power to do this, under the Constitution? Are the powers of the creature, greater than the creator?

Mr. Harris: The Senator from Pennslyvania has a proposition which I think is a heresy under our system of government. His argument is based on the proposition that where the people of a State are unanimous in repudiating the Government of the country we have no right as a General Government to suppress that rebellion. Sir, how does the Senator know, how does any one know, that there is a loyal man in South Carolina? The presumption is against it; and according to the doctrine of the Senator from Pennslyvania, unless it happens that there is some loyal man or woman in South Carolina, the war as against South Carolina is unjust."

Note: Whether he knows it or not, Senator Harris has hit the mark. The whole nonsense of debate, argument, theory, law, etc, turns ultimately on a finding of whether the war is unjust? The answer is beside the point. Governments, since their appearance among the human race, all will use force to maintain a grip on territory, regardless of who wins the argument whether the war that results is just or unjust.

Mr. Cowan: Is not the very thing we are trying to ascertain is whether the war is just?

Mr. Harris: I think not.

Mr. Cowan: Is not the very thing we are trying to discover whether there are enough loyal people in the South to maintain a government with our help against the rebellion? If they cannot, the rebellion succeeds, and then, instead of being a rebellion it is a revolution, legitimate, and goes on.

Note: Here we have a definition that makes sense. A "rebellion" is a resistence to rule by some percentage of a people less than its whole; a "revolution" is resistence to rule by the "whole" of a people. In the context of 1862, there is no question but that, under the Constitution, each State being "sovereign" in its domestic affairs, what counts in the equation is the "whole" people of a State, not the "whole" people of the Union. The "Union" was not conceived, under the Constitution, to be the Union of a people, but a Union of States.

Mr. Harris: I do not so understand it. My idea of this thing is this: that, assuming the whole people of South Carolina are in support of the rebellion, it is our duty, under the Constitution, to put down that rebellion, to suppress it; and having done that, what next? The people of South Carolina say, `You have conquered us, you have by physical strength suppressed our determination to go out of the Union, but you will never hold us to the Union notwithstanding. Now, what is to be done? We cannot force these people to hold a convention, make a constitution and a government, hold elections. But we can do this, we can say to them, "we will enforce upon you the laws and constitution you made when you were part of the Union. (Mr. Sumner, of course, is saying, "we will force upon you our political idea of what good domestic policy is.)

Mr. Cowan: Is this enforced government you talk about, pressed on the people of South Carolina, to remain permanently? If you answer yes, is this then not conquest and subjugation? What is conquest? What is subjugation? Conquest simply means the overrunning of a country and the assumption of its political power on the part of the conqueror, and maintaining it as against the will of the people. What is subjugation but the making the people go under the yoke? I thought this was not our objective.

I have no doubt there are gentlemen here in favor of subjugation, and were from the very beginning, because almost everything that they have done since then has indicated that that was their original intent, but I say that was not the original idea of the American people. We, as a nation, are responsible before the world and to ourselves for the honesty of our motives and the correctness of our intentions.

Note: This is a crucial point to understand about the phenomenon of Lincoln. At the time of his inauguration, in March 1861, he knew that the people of the Northern States thought of the seceded States as sovereign entities entitled to leave the Union if that was the wish of their people, and that they had no feelings which motivated them to engage in a war of conquest. For that reason, he instigated the war as a means of inciting their passions and then used the apparatus of the Republican Party machine to quickly establish an army and send it to do battle in the field. Once the body bags came home, nothing would stop the acceleration of the war. Politicians in the White House have been doing the same thing time after time: Viet Nam and Iraq come immediately to mind. And now we hear noise about Iran. The fault, of course, lies not with them but with ourselves.

Mr. Wilkinson, of Minnesota: I wish to ask the Senator from Pennsylvania a question; does the Government not have the right to prevent another government from being established in its borders, even if the whole people of a certain area determined so to do?

Note: See how tricky the language is? Mr. Wilkinson assumes that the Federal Government owns the territory comprising the State of South Carolina. But if this were so, then, of course, it is impossible to call South Carolinia a "State."

Mr. Cowan: We have a right to maintain the integrity of the Republic, of course, under certain conditions; but as nobody supposes the Republic will be eternal, that it will last always, and that it can last against the will of the people who created it, I leave the answer to my colleagues.

Note: Mr. Cowan says some very heavy things. These men, in their debates, take political theory and language to as high an elevation as did certainly the men who attended the Constitutional Convention, in 1787.

At this point Mr. Fessenden asked for priority to present the Tariff Bill and the motion was agreed to.

July 8, 1862

Message From The House

A message was received from the House of Representatives, by Mr. Morris, Chief Clerk, announcing that the House had insisted upon its disagreement to the amendments of the Senate to the bill of the House (No. 471) to confiscate the property of rebels insisted upon by the Senate, agreed to the conference asked by the Senate on the disagreeing votes of the two Houses, and had appointed Mr. Thomas Eliot of Massachusetts, Mr. James Wiley of Iowa, and Mr. Erastus Corning of New York, managers at the same on its part.

Note: On July 8th, President Lincoln went on board the steamer Ariel, and traveled to Harrison's Landing. There he questioned McClellan's corps commanders regarding their views whether the Army should remain where it was, or remove itself to the Manassas Plain. The majority expressed the opinion that the Army should stay. Before he left Washington, Lincoln had sent Rhode Island Governor Sprague to talk to General Halleck at Corinth, to feel out his willingness to come to Washington as "General-in-Chief." Lincoln returned to Washington on July 10th and immediately issued an order to Halleck that he come.

At Harrison's Landing, McClellan handed Lincoln a letter which contained recommendations of military and political policy that were at the heart of the debate going on in the Senate at the time, policies which would be rejected by the Congress at the end of the session and which, for the most part, were already dismissed from Lincoln's mind.

McClellan wrote, "Military

power should not be allowed to interfere with the relations of servitive,"

but in the next sentence he said, "Slaves seeking military protection

should receive it." How these two statements can be reconciled I cannot

say. He repeats himself in this contradiction when he wrote, first, "This

should not be a war looking to the subjugation of the people of any State. It

should not be a war upon a population, but against armed forces. All private

property should be respected and protected." And, then, second, "The

right of the Government to appropriate permanently to its own service claims to

slave labor should be asserted  and the right of the owner to compensatioon

recognized."

and the right of the owner to compensatioon

recognized."

Whether McClellan was simply stupid, or just motivated to speak out of both sides of his month like a politician, who can say? What is clear is that by the time he reached Harrison's Landing, Lincoln had made up his mind what his policy was now to be: The war would be against the civilian population of the South, forcing them by conquest to give up their domestic institution of slavery in the process. If slavery caused the war, the war caused the emancipation of the Africans. It is a fact they ought to respect.

July 9, 1862

The Militia Act

On motion of Mr. Wilson, of Massachusetts, the bill (S.No. 384) to amend the act calling forth the militia was read a second time and amendments offered.

Mr. Grimes, of Iowa: I offer this amendment: be it further enacted that there shall be no exemption from the performance of military duty under this law on account of color or race, but whenever the militia shall be called into service, all loyal able-bodied males persons shall be called to the defense of the Union.

The PRESIDING OFFICER. The question is on the adoption of the amendment proposed by the Senator from Iowa.

Mr. Saulsbury, of Delaware: On that amendment I ask for the yeas and nays.

The yeas and nays were ordered.

Mr. Saulsbury: It would have been utterly impossible, had this war been really prosecuted for the restoration of the Union as it was, for the people to ever allow the Union to be dissolved. But no sooner did the war commence that an attempt is made on every ocassion to change the character of the war and to elevate the miserable nigger, not only to political rights, but to put him in your Army, and while this policy is pursued the Union will never be restored, because you can have no Union without the preservation of the Constitution.

Note: Mr. Saulsbury, a Democrat, was the most uncouth among the senators in the use of language, though some other of them earlier used the word "wenches" to refer to African women. Most of the senators referred to the Africans as "negroes," or "colored people" or "blacks."

Mr. Carlile, of Virginia: I desire to inquire of the Senator from Iowa if negroes constitute a part of the militia of his State. I know they do not constitute a part of the militia of the State in which I live, and I am not aware that they constitute a part of the militia of any State in this Union. As I caught the reading of the amendment, it provides for enrolling as a part of the militia the negroes of the country. Now, sir, who constitute the militia is settled by the laws of the several States and I hold the Congress has no power to determine who shall compose the militia of the States in this Union. This is a subject of State regulation. I do not think this amendment is an effort to elevate the negro to an equality with the white man, as the Senator from Delaware does; but I do think the effect of this legislation will be to degrade the white man to the level of the negro.

Mr. Saulsbury: I accept that suggestion.

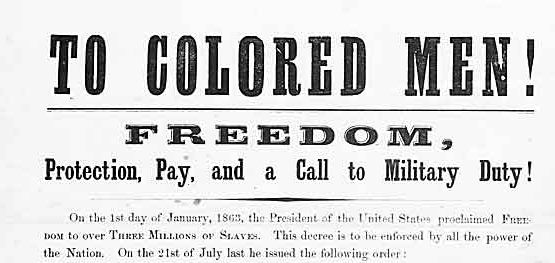

Mr. King, of New York: Let me move to amend Mr. Grimes's proposed amendment with this: be it enacted further that the President is authorized to receive into the service of the United States, for the purpose of constructing intrenchments, or performing camp service, or any other labor, or any war service for which there may be found competent persons of African descent, and such persons shall be enrolled and organized under regulations, not inconsistent with the Constitution; and that whenever any such person serves the country in this manner, he, his mother and his wife and children shall be forever free, any law to the contrary notwithstanding.

Note: Mr. King's proposed amendment runs afoul of the realities of slavery. The civil law of the slave States did not recognize that a male African slave might have a "wife."Ditto, for "children." One white citizen might "own" the male," another the "wife," another the "children."

Mr. Grimes: I accept the provision if I have the power to do so.

The PRESIDING OFFICER. It may be done by unanamious consent. Is there any objection? The Chair hears none.

Mr. Saulsbury: I wish to know what is the question before the Senate?

The PRESIDING OFFICER. The Senator from New York proposes to strike out the first two sections of the amendment of the Senator from Iowa and insert instead what has just been read.

Mr. Saulsbury: The proposition is to authorize the President to call into the service free negroes. This is a wholesale scheme of emancipation. Under this proposition the President can go into any State and call into service every slave and if he does that your law makes the slave and his family free. The work goes bravely on, sir. Here is the most magnificent scheme of emancipation yet proposed. How long will you keep the Army in the field after adopting such a policy? Do you believe that free white soldiers of this country will fight side by side with negroes? You will have no armies in the field, in my judgment.

Mr. Sherman, of Ohio: The question must be decided whether the negro population of the country shall be employed only by the rebels. Their labor has furnished the rebels with food, entrenchments, and camp service. The question is, shall the Union employ the labor of a race of men whose interests, whose sympathies, whose whole hearts are with the loyal people of the Union in suppressing this rebellion.

The policy of the officers of the Army so far, has been to repel this class of people from our lines, to refuse their services. They would have made the best spies, and yet they have been driven from our lines. They would have relieved our soldiers from many a hard task, many an irksome duty, but instead of that our soldiers have been made to guard the property of the owners of those slaves. The slaves have been employed to uphold the rebellion and our soldiers have been put as guards around the homes of slaveowners.

I do not believe that the whites and blacks will ever mingle together in terms of equality. I think the law of caste is the law of God. You cannot change it. The whites and the blacks will always be separate, or where they are brought together one will always be inferior to the other. That, however, is not the question now. Here are the blacks in our country, millions of them. They are our natural friends in this war. Now shall we avail ourselves of their services? That is the question.

Note: Mr. Sherman is a Republican.

Mr. Saulsbury: I ask the Senator, is it within the power of Congress to pass this bill?

Mr. Sherman: I have no doubt it is constitutional for Congress, in raising armies, to enroll both whites and blacks, free and slave. And it is equally clear that Congress may, when military service is required, deprive a master of the labor of his slave. But this right is measured by the military necessity and when exercised against a loyal citizen should be accompanied with compensation.

It is true that by the militia law of Ohio, negroes do not muster with whites. They are not enrolled as part of the militia, and why? Because the prejudice of caste separate the white from the black and always will; but in a time of necessity, you have the same right to call on the negro, slave or free, as you have to call upon the Senator from Delaware.

Ordinarily, to arm negroes would be shocking, but now we have to choose between their employment and the destruction of our country.

Mr. President, until we learn a little enegry from those desperate men who are engaged in this warfare against us, we cannot expect to succeed. We must follow, to some extent, their bad example. It is true, that the best mode to conduct war is to regard all persons and all property as exempt except the armed forces of the enemy. But this is a desperate war and our enemy has no problem marching side by side with negroes. The law of retaliation is the only law that will bring these mad men to their senses.

Note: Here, Mr. Sherman expresses in a nutshell the law of nations which the Union Government is about to ignore by establishing the policy reflected in the Emancipation Proclamation. The law of nations does not recognize as an exception to the rule that private property of civilians may not be confiscated, that the war is "desperate;" only "military necessity" provides an exception and the armies' use of such property must be limited to the time in which the necessity exists.

Sir, I think the time has come when we must seize the slaves of the disloyal, when we must seize their property, when we must inaugurate their system of warfare and array the whole physical power of this country and enter this war in earnest. If it is necessary to put down this rebellion I would arm the slaves and let them march and live upon the country wherever they go. Suppose Jeff Davis with his army should go into Maryland and Pennslyvania, do you suppose they would pay, dollar for dollar, for everything they take? If they were to reach a region of the country which does not recognize their authority, they would burn and desolate and rob and plunder and murder.

|

I tell you, Mr. President, that you cannot conduct warfare against savages unless you become half savage yourself. I do not know any other way to bring this war to an end.

Mr. Fessenden, of Maine: The bill is thought to be a necessity. We might as well tell the truth about it here and have it understood by the country. I am ready to say that, from information received from my State, there is not that readiness to enlist that there was; there is not that enthusiasm with regard to enlistments; men do not rush forward and tender their services as they did awhile ago. The people in my State feel that the war must be conducted on some different principles from those upon which it has been conducted so far; that is to say that, on the part of the military officers, there should not be that extreme tenderness and delicacy with regard to men who have no tenderness, except that of the wolf for the lamb, toward us; that they shall be met with the same spirit that is able to resist a determination and a feeling of that description.

Sir, our soldiers do not like it; they do not feel easy that they are called upon, when it is not necessary, to protect the property of the enemy.

Sir, what do we owe these traitors? What makes some gentlemen on the other side of the Chamber so sensitive the moment that you speak of employing negroes, the slaves of rebels, in the service of the country? Why do they jump to their feet the moment the idea is suggested? Why should we not weaken the enemy and attack him at his weakest point? Do you say we are proposing abolition by it, or emancipation? Not at all. We are proposing simply to use those arms and nothing more. Why should men who come to our camps, be turned away?

Sir, you cannot deal with savages in this way. The man who sets himself to overthrow his government is worse than a savage.

We want more men for this war. Why not say so at once, tell the truth that we want them; appeal to the people, let them know what is required for the sake of the country.

Mr. Rice, of Minnesota: I have only a few words to say. It has now become a certainty with all reasonable men, who have thought upon this subject at all, that not many days can pass before the people of the United States north must decide upon one of two questions: we have either to acknowledge the southern confederacy as a free and independent nation, and that speedily, or we have to speedily resolve to use all means given us to prosecute this war to a successful termination.We are expending the money of our citizens; we are almost daily losing by sickness and otherwise thousands of lives, and at the rate this loss has been going on, it will take but a few months more before our Army is reduced to a state that is worthless.

I admit that at one time I was not in favor of employing blacks. I did not believe it was good policy, but Great Britain employs several regiments of blacks on our border with Canada; if this can be done why can we not do it?

Mr. Wilson, of Massachusetts: In the present condition of the country, with the wrecks of humanity that are floating over the land ruined in health in the military service, or who have been wounded in the field, in view of the fact that death has entered so many families, I believe it will be very difficult at this time to raise, by volunteering, the number of men necessary to support the cause of the country. It seems to me that we need men at once, at the earliest possible moment, and I doubt that we can raise men for the next forty days any faster than will be necessary to supply the actual loss that will take place during those forty days. I believe the bill, therefore, is necessary.

Now a word in regard to the action of the Government in stopping recruiting. The fact is, that for thirty days before the order was issued closing up the recruiting stations, the recruiting had ceased altogether, and we had not raised five hundred men for a month before that order was issued. I trust that the experience of the last few weeks has taught the Government and taught our military leaders a lesson. Sir, the country is flooded today with the letters of your brave volunteers, men among the living and the dead, depicting their suffering in swamps and ditches, toiling to build up fortifications, and their sufferings in guarding rebel property and protecting those who would smite them down in any hour.

Note: This is a very telling statement by Mr. Wilson. It is always easy for a government to draw its people into a war; war is a lark at the beginning, bands playing, young men marching, flags waving, but once the body bags and the maimed come home the reality that war is horrible sets in, and governments, unless they pay huge sums to entice the young people in, have to resort to conscription―after all, don't governments own every single human being under their control? Oh no, some politician cries, "It's merely a feeling of patriotism, a duty of allegiance that rules."

Sir, I am for raising voluntarily every man we can; I am for drafting the last man that can carry a rifle to uphold the cause of the country. This rose water way of carrying on the war must cease.

Now a word about the amendment, to use the loyal colored men to uphold the cause of the country. The Senator from Delaware asks if American soldiers will fight if we organize colored men for military purposes. Did not American soldiers fight at Bunker Hill with negroes in the ranks? Did they not fight on the battlefield with American soldiers in Rhode Island? Did they not fight on every battlefield of the Revolution? It is said that General Halleck built two hundred miles of corduroy road, and forty-five miles of fortifications. Everyone knows the great burdens on the Army of the Potomac. The shovel and the spade and the ax have ruined thousands of the young men and sent hundreds of them to their graves. We could have employed thousands of colored men at low rates of wages to do that ditching, and thus save the health of our soldiers.

Note: Is this exploitation, or simply quid quo pro—freedom for labor in dangerous circumstances?

Mr. Davis, of Kentucky: I am for the reconstruction of the Union. I believe the only principle and means by which that reconstruction is possible, is by the employment of the full legitimate military power of the country, and not by arming slaves and attempting to form a military force of them.

Note: Mr.Davis is, like Cowan, a close thinker who has a clear grasp of the political realities.

I have

no issue with negroes digging ditches. We hear that the general in charge of

the army down around Vicksburg has employed thousands of them to dig a ditch.

When a general is commanding in the field, and he has occasion for the labor of

horses and oxen, what does he do? He impresses them into the service of the

Army. Just so, if that general may need the services of negroes for the purpose

of fortifying, or ditching. But when the general has done with the negro, the

negro is no longer useful in his camp for the purpose of labor, let him be

discharged, sent away like other property. I protest against placing arms in

the hands of the negro and making a soldier of him.

I have

no issue with negroes digging ditches. We hear that the general in charge of

the army down around Vicksburg has employed thousands of them to dig a ditch.

When a general is commanding in the field, and he has occasion for the labor of

horses and oxen, what does he do? He impresses them into the service of the

Army. Just so, if that general may need the services of negroes for the purpose

of fortifying, or ditching. But when the general has done with the negro, the

negro is no longer useful in his camp for the purpose of labor, let him be

discharged, sent away like other property. I protest against placing arms in

the hands of the negro and making a soldier of him.

Has it come to this, Mr. President, we have run out of white men enough to put down this rebellion? We must rely on the negro? I protest against such a degrading position as that.

I know the negro well; I know his nature. He is, until excited, mild and gentle; he is affectionate and faithful, too; but when his passions have been inflamed and aroused, you find him a fiend, a latent tiger fierceness in his heart, and when he becomes excited by a taste of blood he is a demon. Such is the nature of the race.

Note: Such is the nature of man.

Mr. Wilkinson: I wish to remind the Senator from Kentucky of the proclamation which General Jackson issued after the battle of New Orleans, complimenting his negro soldiers for the manner in which they conducted themselves. The Senator seems to think that negroes are inhuman when they once smell blood. I send to the desk the proclamation.

Mr. Davis: Mr. President, the proclamation was not addressed to slaves, but to free colored persons. The mulattos of New Orleans, educated businessmen, men of intelligence.

Mr. Wilkinson: Mr. President―

Mr. Davis: No, sir; excuse me if you please. In the extreme stress at New Orleans General Jackson did not propose a conscription for all the slaves, or any of them, much less to emancipate them, but summoned the free colored people.

Now, do you want these seceded States back? If you force them back, and cannot change their heart, they will only be a source of unceasing trouble, expense, disturbance, and war to the rest of the nation. If the work is to be done at all, you must adopt a line of policy that will build up a Union party in the South, and to that you must hold up to them the Constitution with none of its provisions broken.

|

When you ask us, will you take general confiscation of the property of all the disloyal; abolition of slavery, the slaves to remain in their localities; will you agree to our arming them and making them soldiers to fight the battle of the Constitution, which Constitution guaranted them as property to their owners, will you take all these atrocities? We answer, never! Never! never!

If this Union cannot be preserved by the white man, there are no conditions upon which it can be saved. If you put arms into the hands of the negroes and make them feel their power, you will whet their fiendish passions, make them the destroying scourge of the Cotton States, and you will bring on a condition that will make restoration hopeless. |

Mr. Rice: The Senator's whole argument has gone to show that we of the North were making war upon the border States, upon the Union men of the border States, and he has held up to us the atrocities that will be committed upon his family and upon the families of the Union men in the border States. Who is it, sir, that has defended the Union men in the border States and those pretending to be Union men? It has been the North. They have saved their wives and children and property. I am not in favor of massing the negroes and putting arms in their hands, but I am in favor of employing them in this war. If you look at the history you will see that 300,000 Confederate soldiers are worth 500,000 of ours. Why is this so? All the building of roads and bridges, all the camp duty, all the menial services among them is performed by negroes.

I was much gratified at one remark the Senator made; and that was if the southern confederacy is successful, it was not the end of secession. That I believe. If they were successful in this contest, the northern States, the free States, would soon divide; first, the West from the East; and eventually mountain range and every lake and principal river would form the boundary line of some petty principality. Such being the case I deem the Union worth saving and every loyal man should be willing to contribute his last dollar and his last meal in its defense.

Mr. Davis: Will the honorable Senator allow me to ask him one question?

Mr. Rice: Certainly.

Mr. Davis: If the Confederates violate the usages and customs of war does he want our Government and our armies to be guilty of the same violation?

Mr. Rice: If a stranger had been here to listen to your speech he would think you are the ambassador from the Confederacy speaking on its behalf.

Mr. Davis: Mr. President—

The PRESIDING OFFICER. The Senator from Minnesota is entitled to the floor.

Mr. Davis: I say that I have said nothing that authorizes him to make that statement.

Mr. Rice: The Senator has spoken as though the people of the North are warring on him.

Mr. Davis: It is not so.

Mr. Grimes: I call the Senator to order.

Mr. Davis: Let the gentleman protect himself.

Mr. Rice: I have no objection to the Senator venting himself any way he wishes.

Mr. Wilson: I move that the Senate proceed to the consideration of executive business.

On motion of Mr. Wilson, the Senate proceeded to executive business.

July 10, 1862

Army of the Potomac

Mr. Chandler, of Michigan: I move now that the Senate move to the consideration of the resolution offered by me a few days ago. (The resolution is to ask the President to produce all communications between the Government and General McClellan relative to his advance against Richmond.)

Mr. Wright, of Indiana: Mr. President, when the resolution was read the other day, I could not refrain an expression of surprise that in the midst of such a crisis as the present that an inquiry should be set on foot, the result of which must be to divide the friends of Union and to unite the enemies of the Union. The Senator proceeded in language and manner sufficiently violent and declamatory, to give the impression he meant to bring contempt and dishonor upon General McClellan. It is not to my taste to go back to the field of Manassas and to say that two hundred thousand men were held at bay by less than 30,000 rebels. I know little of the art of war. I am willing to trust the men in command of the Army. Judging from the explosive rhetoric of the Senator who takes pains to call General McClellan a criminal.

Mr. President, General McClellan has not been a newspaper general. He has not sought to write himself into renown, or court others so to do. Not one word has General McClellan offered to defend himself against the charges of the Senator. His reticence and silence has been remarkable. A more implusive man―and we are told that youth is most impulsive and General McClellan is a very young man—would have rushed into print and insisted upon such a defense of his conduct as would at least assure his friends that was not indifferent to his fame. His studied silence is probably his surest vindication.

I will say that, in my humble opinion, that his ten days campaign upon the peninsula, with an army that he tells us was so much smaller than that of the rebel enemy, out-tongues complaint, and will arouse admiration among our loyal people. Some will say that the general was surprised and taken unaware, and that all the allegations that his moves were planned are untrue. I will say only that the conflict displayed on his part uncommon genius, perseverance, and ability; that his troops were heroic and that he saved them from annihilation and captivity. Sir, I know not where in the history of nations you can point to a seven days' conflict, with the same number of men engaged, where there was more science and skill exhibited by the commander than General McClellan exhibited in this contest.

What must be the feelings of that general when he is charged upon this floor with disloyality; when it is promulgated in this body that every move of his for the last six months would be precisely what Jeff Davis would have desired? Is it possible that we can sustain this Government in this way?

Mr. Chandler: Mr. President, the Senator from Indiana misunderstands me. It is well known that the press for weeks has been filled with denunications of the Secretary of War, calling for his removal, and for what? For failing to have furnished McClellan with reinforcements. I admitted what the press claimed, that a crime had been committed. I denied that Stanton was the criminal and I simply asked for the evidence that he was a criminal.

What are the facts of the case? I stated that the Army of the Potomac, on the day that it marched to Manassas, had two hundred and thirty thousand soldiers upon its rolls. When that army was divided and a large force taken to the peninsula, it was well known that a portion of that army was to be left behind to protect the capital. It was decided that forty-five thousand men should be left here to defend the capital. The evidence shows, though, that McClellan left behind only nineteen regiments. The President at once ordered an army corps to stand between the enemy and Washington. Had McClellan's order taking all away but nineteen regiments been carried out, Jackson would have been in Washington before the 15th of April, but the President intervened. I say the President and Secretary Stanton have sent to McClellan every man that could be spared from the defense of Washington. Is it not proper that the country know this evidence?

Note: It was just not militarily possible that Jackson, with at that time two divisions of infantry, could have gotten as far as Jubal Early did with a corps in 1864, much less had gotten in Washington.

Mr. Saulsbury: I am not disposed to meddle in this matter, but I want to know what number of soldiers there were in the valley of Virginia, in West Virginia, and in front of Washington and also at Baltimore.

Note: Mr. Saulsbury has touched on the tender point: Lincoln had control of over 45,000 men operating independently of McClellan; he simply put them to uses that took them away from the Manassas Plain, and then he complained he didn't have enough men.

Mr. Wright: What does the Senator from Michigan want? He says he wants the record. Has it come to this, that in a controversy of this kind the newspaper press of the country, that has slandered McClellan, is to be the basis of a resolution of the Senate?

Let me say this finally. I do not know General McClellan. I have never met him in my life. But the idea the Senate is to pass resolutions, calling for this and for that, distrusting our generals, is not good for the army. I will never vote for a resolution that implies there is any doubt of the capacity of this general, or that he has not discharged his duty.

Mr. Henderson of Missouri: Let me say that I have utmost confidence in General McClellan. I believe he is true and loyal and that he has performed military service in the field in the last two weeks that will most inevitably distinquish himself beyond all men of his day as a military commander. But, sir, it will not do for us, every time our Army may meet with a little reverse, to rise in the Senate and denounce and charge treason upon the commander.

There is a mistaken notion in respect to the strength and power of this rebellion. I know that the newspapers throughout the North have been in the habit for the last six months of disparaging the power and ability of the rebels to hold out against us in this rebellion. They have invented new terms of reproach. They have again and again said that the rebels will not stand and fight us. In fact, they have invented a new word, `skedaddle' and applied it to the rebels. They say the rebels will run from our troops. I have never thought so; and we shall find out from this day forth, as we have found it heretofore, that they will meet us on the field of battle and fight with a bravery and courage equaled only by the bravery and courage of our own troops; and it is useless any longer to conceal the fact from the country. It is useless, when a reverse happens, for the Senate to say it is a consequence of treason in the commander. It is stupid so to talk.

Sir, this is a great work we have undertaken. It is an immense territory we have undertaken to conquer. Such a territory and such a number of people have scarcely ever been conquered in the world. This is the first reverse we have suffered in some time. Senators have been unable to bear it.

Sir, if the Army of the Potomac is immediately reinforced, and a sufficient number of men given to General McClellan, now is the time to march upon Richmond, and the rebel capital will fall within the next month. Let that be done and the complaints done with against the commander. They are only calculated to divide the loyal men of the country. It has been suggested that if an attempt is made to remove McClellan the army will rise in his favor. Sir, away with such things as that. If he proves to be incompetent let the President remove him at once, and put another man in his stead, and the loyal men will sanction it.

Note: Here is highlighted Lincoln's dilemma with McClellan. McClellan was very well liked by his troops, by civilians at home, and by a strong contingent of senators and, for that matter, governors. Peremptorily removing McClellan and substituting somebody else in his place, Lincoln obviously decided, could not be done. Just as he had finessed the onset of the war, Lincoln now was moving to finesse the ouster of McClellan.

The newspapers have told us for months that the rebels are starving to death, that they have no cannon, no rifles. Why, sir, this is pure ignorance. When we meet them upon the battlefield, we shall find that they are men of our own race, of our own blood, and as brave as we are.

Let me say, too, that it is said by some of you on that side that we border State men are less loyal than you. Let me tell you, sir, that we ought to understand ourselves better. Suppose that Kentucky, Missouri, and Maryland had joined hands with this rebellion at an early day, and passed ordinances of secession, I ask you what would have been the success of our arms? It is true Missouri put into the rebel army about ten to twenty thousand men; but we put into the Union army forty thousand men, and we are ready to put the twelve thousand that may be apportioned to us under the recent call into the field, and if that is not sufficient we are ready to put in twelve thousand more. We are ready to give the men, to give the means, to do everything necessary to crush this rebellion and to restore the Union again as our fathers made it.

Note: As Lincoln intuitively knew, had the mass of Missouri's young men gone to the Confederate Army, coupled with the mass of Kentucky's, Grant's army, as well as Buell's, would have been crushed at Shiloh.

|

And let me say another thing, about this negro business of soldiering. You may honestly believe it is a proper plan to seize upon the negroes of the South and to use them as soldiers. I should regret it. You may muster as many as these black soldiers as you please, but I tell you when you muster them in, you must send two regiments of Yankees to stand behind them, and then there will be a great danger of those regiments being run over by them when the firing begins. They will not make soldiers. You cannot make soldiers of them. But, sir, I have wandered from the subject. If General McClellan is loyal, and I believe he is, he should remain at the head of our forces. If he is incompetent― |

Mr. Chandler: Mr. President, I wish to correct a statement that I have charged General McClellan with disloyalty. I charged him with no such thing. I said I considered the divison of the army and the sending of half of it to the peninsula as a great military blunder. I made no charge of disloyalty.

Mr. Henderson: No man with the military science of General McClellan, unless his heart be corrupt, would ever have blundered accidentally upon all the scientific moves Jeff Davis would have made. Had we, here, not spoken up, it would have gone to the country that we think the man who was conducting our armies was designing, by every movement he could make, to put our armies in the hands of Jeff Davis. I am glad you have set the issue of disloyalty to rest.

Mr. Trumbull, of Illinois: I regard it as a little singular that Senators rise and seek to lay it down as undisputed that General McClellan has done exactly right. The Senators say that General McClellan does not stop to defend himself. He does not enter the newspapers, nor do his friends for him. Have not the Senators read the newspapers of the last ten days, filled with articles showing the strategic ability of McClellan, showing how he was drawing the enemy into a trap?

Note: On June 26, as the battle of Gaines Mill was playing out, Mac wrote his wife, Mary Ellen: "I believe we will surely win and that the enemy is falling into a trap." According to Webster's Dictionary, "trap" means "any stratagem designed to catch an unsuspecting person."How his falling back to Harrison's Landing might constitute a trap for General Lee, McClellan does not say.

If the Senator from Missouri had been told that all the armies of the Union, half a million men, were to be placed under the command of a single individual, and that individual was to have marshalled under his immediate command two hundred and thirty thousand men, with authority to control all the other troops of the Union, and he was to hold these men under his command not only for ninety days, but through the whole season of the fall of the year, through the whole winter, through the whole spring, and into midsummer, and never make an attack upon the rebels—would he have selected an individual to command who has done that thing, if he were told this a year ago in July?

Note: This is an exact statement of the case.

Mr. Henderson: I will repeat what I said before. That the country has been in error as to the strength of the rebels. I recollect when General Sherman, in Kentucky, at one time said it would require one hundred thousand―[Mr. Davis. Two hundred thousand]—to proceed through the State of Kentucky, the newspapers said he was deranged. I recollect that afterwards, when our forces undertook to go through Kentucky, it took over one hundred thousand men.

Mr. Trumbull: Now, I wish to say a word about this over and underestimating the force of the enemy. I disagree entirely with the Senator. The difficulty is that we have been overestimating the force of the enemy. We have been acting on the defensive.

We are engaged in a war to put down a rebellion. It is not a war with an independent nation, where we may wait upon that nation to attack us, but it is a war with rebels, and for every day that the war is prolonged the rebels gain strength; their government becomes consolidated, men become accustomed to that Government, and their interests become identified with it.

Note: Here, again, crops up the difference in concept, of theory, of the political nature of the war. If Lincoln's Government were to have waited for the Confederacy to attack it, it would have waited quite awhile, as history records the undisputed fact that the Confederacy was not acting the part of a military agressor. It was not in the shoes of the United States attacking Japan, Germany, Viet Nam, or Iraq. It was in the shoes of a country defending itself against a stronger power intent on conquering it.

How can you have unbounded confidence in a general, under such circumstance, who for a year has not struck a blow? Has the general ever made an attack, or has he always waited to be attacked? Can a rebellion ever be put down by acting on the defensive, by building entrenchments, by waiting for the rebels to come and attack you?

Note: Trumbull's use of the phrase, "strike a blow" is the theme of the agressor; to conquer you must strike blows. You must charge the enemy out. On April 6, 1862, as McClellan approached Yorktown, Lincoln wrote him: "You now have over 100,000 men. I think you better break the enemies's line at once." Three days later, on April 9, when McClellan said he had only 85,000 men, Lincoln wrote him: "I suppose the whole force is with you now; and if so, I think it is the precise time for you to strike a blow. . . You must act."And on April 10th, Lincoln wrote McClellan, "I think it is the precise time to strike a blow. . . and once more let me tell you it is indispensible to you to strike a blow." On May 1, Lincoln wrote McClellan: "Your call for the Parrott guns argues indefinite procrastination. Is anything to be done?" On May 25, incredibly, Lincoln wrote McClellan this―"I think the time is near when you must either attack Richmond or give up the job and come to the defense of Washington."On May 26, he wrote, "Can you get near enough to throw shells into the city?"

I have heard the strength of these rebels stated here time and again. There are only four or five million white people with whom we are contending; a very little larger population than there is in the State of New York; and the whole rebel States are not equal today in arms, in materials of war, or anything else, to the State of New York alone. She is compact; she could bring her men into the field promptly, while these southern States extend over thousands of miles, with a scattered population, and a large slave population that has to be looked after, and yet we are told we have underated their strength. Sir, we have overestimated it, and waited to act on the defensive, instead of striking this wicked rebellion, and crushing it by active movements upon it; that has been the trouble.

Note: ". . . crushing it by active movements upon it."The politicians are pressing Lincoln to do this and Lincoln is pressing his generals, both Halleck and McClellan, to do this; and, instead of the politicians' idea of what "active movement" means, the generals, both of them, are following the principles of military science, taught to them at West Point, husbanding their resources in manpower, as they advance prudently to close with the enemy in a desperate life and death struggle for a strategic point.

McClellan's big guns almost within range of Richmond

I shall not go into the conduct of General McClellan. I shall express no opinion about it. The country can judge for itself when it sees the results. The country sees that weeks and months were spent in digging intrenchments and throwing up fortifications, and that thousands of lives were sacrificed, and yet when the enemy approaches, your intrenchments are left and your guns hauled away without scarcely the appearance of a battle. The battles that were fought, were fought outside of the intrenchments and on the retreat and the enemy had all the benefit of pursuing a retreating foe. We know, sir, that the retreat was ordered from the west side of the Chickahominy without any considerable battle taking place Friday night. True, sir, a battle had been fought on the east side of the river in which a small portion of our troops were engaged, where they met and were overwhelmed by a superior rebel force. I hope this resolution may be passed, so the country knows what happened.

Mr. Wilson: I move to take up the bill to augment the Militia with negro soldiers.

Several Senators: Let us vote on the resolution.

Mr. Chandler: If the Senator will give way I think we can have a vote.

Mr. Wilson: I have given way and we have got speech after speech.

Mr. Anthony: I hope the Senator will not give way. This debate will last all day.

Mr. Davis: I understand that what has produced this resolution is the attacks by the newspapers upon the Secretary of War. I think he deserves censure. In a short time after his appointment he manifested a very great hostility toward General McClellan. When General Lander had a small, but successful skirmish with the enemy, Stanton published a proclamation praising Lander and censured McClellan. McClellan had explained the reason he had not moved toward Manassas was the condition of the roads, and Stanton used Lander's success to show that the roads were passable. We all know, too, that Stanton entered into an intrigue in the Cabinet to induce the President to remove General McClellan but the President did not agree.

Mr. Wilson: I took that as a mistake.

Mr. Davis: As a consequence of Stanton's intrigue, General McClellan was induced to lay his plan of campaign before a board of generals, twelve in number, and eight approved it and four disapproved it. I know that Stanton has been inimical to McClellan, and that he has time after time controverted his capacity for command, that he has issued a stream of disparagement against McClellan and I condemn him for it.

Mr. Chandler: The Senator is mistaken as to the council. That council was held to decide whether the enemy should be attacked at Manassas or left alone, that the Potomac should be left blockaded, and the army should be taken to Annapolis and shipped to the rear to attack, the council approved this, and the President rejected it, insisting that the army go to Manassas and attack directly.

Mr. Wilson: I do not think the Secretary of War disparaged General McClellan at all. As I understand it there were three plans to go to Richmond. One, I think, originated with General Rosecrans, and that was to make the movement up the Shenandoah Valley, because it could furnish sufficient supplies for the army as it moved, and then it would approach Richmond from the right direction, throwing the enemy toward the tidewater. I understand Stanton thought this the best movement. There was another plan, to go to Fredericksburg, and from there move on Richmond. Then there was General McClellan's plan. I know a great many men who believed that was not the best plan. They are confirmed in it now.

The PRESIDING OFFICER. The question is now on the resolution. The question being taken by yeas and nays, resulted―yeas 34, nays 6. So the resolution was agreed to.

The Militia Act To Make Africans, Soldiers

On motion of Mr. Wilson the Senate, as in Committee of the Whole, resumed consideration of Senate Bill (S,No. 384) to amend the Militia Act.

Mr. Collamer: The Constitution provides that the militia shall be organized by act of Congress. The Congress, in 1792, passed a law organizing the militia, and in that law it was provided that the miltia should be composed of all free white male citizens. But in relation to the Army there is no law forbidding the enlistment of colored people.

I see that some confusion has come over us in regard to volunteers and militia. Volunteers are really militia raised by the States, commissioned by Governors. The confusion comes because we passed an act that allows the President to call for volunteers directly which he can organize as United States Volunteers outside the State militia system. Under that Act the President gave out orders forming brigades and divisions. I do not understand why the Government has not the right to the use of every man in the country, black or white, for its defense, and every horse, and every particle of property, every dollar. That is the eminent domain.