What Happened In March 1862

III

The War in the East

| What Happened in March 1862 |

Hampton Roads

On the 8th of March 1862, the United States Navy had at anchor in Hampton Roads five warships of the line—Minnesota, Roanoke, St. Lawrence, Congress, and Cumberland—plus many support vessels, steamers, tugs, and barges; all of these ships were supporting the Union troops that were operating against Confederate defenses on the Carolina coast, at Port Republic and Roanoke Island. Shortly after noon "three small steamers" were sighted coming around Sewell's Point. Soon, as the sailors were running to the general battle stations, the report came from the lookouts that one of the approaching vessels was the C.S.S. Virginia.

U.S.S. Virginia Steams into Hampton Roads

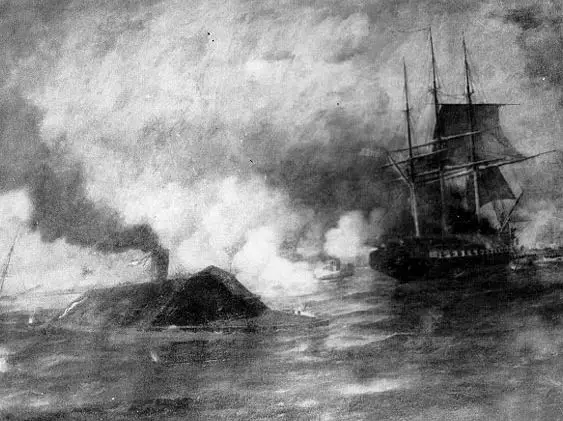

The Virginia stood straight for the Congress and the Cumberland which opened their guns on her as she came within three-quarter miles range. With cannon balls slamming against her iron sides, the Virginia steamed pass the Congress directly toward the Cumberland and rammed into her starboard side, opening a great rift in her side and she began to sink. Backing out, the Virginia, still under fire from the guns of both enemy warships, turned, and standing broadside to the stern of the Congress, threw shot and shell into her as she slipped her anchor and her sailors scrambled into the rigging to set foretopsails, her captain endeavoring to move the ship closer to shore to get under the batteries of Fort Monroe, but as the ship was maneuvered it ran aground in the shallows.

C.S.S. Virginia Rams U.S.S. Cumberland in Hampton Roads

Stuck fast in the shallows, the Congress kept up a fire with her pivot guns for about an hour, with the Virginia, lying off her stern boring her through and through with shells and finally setting her on fire. As the fire exploded the ship's magazine, throwing a ball of flame through her rigging, two Confederate gunboats, armed with rifle guns, dismounted the Congress's stern guns, so that she became entirely helpless. The colors were hauled down and the ship surrendered. Taking off the crew in the gunboats, the Confederates left the ship to burn down to the waterline.

C.S.S. Virginia Blasts U.S.S. Congress

Everything on the exterior surfaces of the Virginia had been badly damaged by the fire of the enemy guns: the muzzles of two of her guns were shot off, the anchors, smokestack and steam pipes were shot away, railings, stanchions, boat davits, everything on the outside of the vessel were swept clean. In the interior, notwithstanding the vessel's heavy armor, the crew had taken twenty-one casualties.

During the Virginia's attack on Cumberland and Congress, the Minnesota, Roanoke and St. Lawrence attempted to reach the scene but they ran aground off Fort Monroe. Recognizing this, the Virginia, late in the afternoon, turned toward the Minnesota, helpless now on the shoals, and began steaming across the road, but, upon reaching the middle channel, found the ebb tide made the passage too dangerous and she was turned round and steamed out of sight behind Sewell's Point. As she did this, with dusk settling over Chesapeake Bay, the U.S.S. Monitor came steaming between the capes and entered the road.

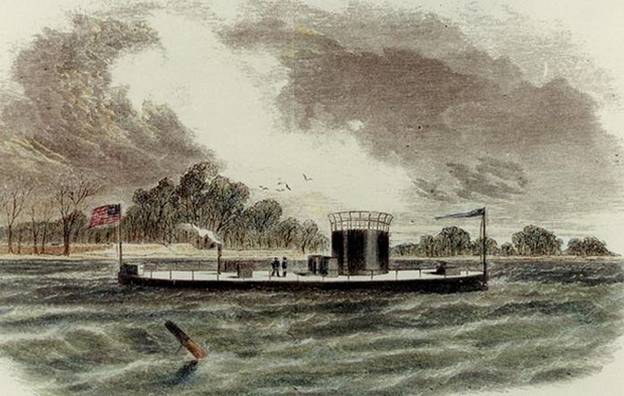

U.S.S. Monitor

After six months of construction and trials, the U.S.S. Monitor put to sea from New York Harbor, on March 6, 1862, and, towed by the tug, Seth Low, steamed south in stormy weather that twice almost caused her to flounder. Despite chalking around the turret, the sea water came into the interior of the vessel like a waterfall, causing the belts of the blower-engines to slip, the steam pressure to fall, and the engines consequently to stall. These conditions, in turn, produced a mixture of gasses which filled the engine room, forcing the crew to abandon the space as some were passing out from the lack of fresh air.

Monitor Awash At Sea

With the chief engineer and his assistants unconscious from the fumes, Alban Stimers, the vessel's construction foreman, was the only man on board who understood how to operate the engines and pumps. Fumes were now filling the entire ship and the water was rising. Stimers set the crew to bailing by forming a bucket brigade up the turret ladder. Stimers sent men, in quick relays, into the fireroom in an effort to get the blowers, engines, and pumps operating again. As this was being done, the Seth Low altered course, bringing the Monitor closer to shore and into calmer waters which relieved the situation for a time; but then the heavy seas broke the vessel's tiller ropes and she floundered again. Stimers, though, was able to restore control of the helm, and this allowed the ship to move on, and it anchored in Hampton Roads just as the Virginia had retired behind Sewell's Point.

The

news of the Virginia's appearance in Hampton Roads and the destruction of the

warships, Cumberland and Congress, with the loss of

300 men, shocked Lincoln and his cabinet. Edwin Stanton, the Secretary of War,

met with Lincoln at the White House the morning of March 9, and pacing the

Cabinet Room with baleful glances at the men assembled—McClellan, Secretary of

the Navy Gideon Welles, Secretary of State William Seward and others—he almost

shouted in his anxiety that the rebels would destroy the Union fleet, capture

Fort Monroe, and be at Washington before nightfall. "Why, sir, it is not

unlikely that we shall have from one of her guns a cannonball in this room

before we leave it," he had burst out at one point. Welles responded, he

says, to Stanton's hysteria, by saying that the Monitor was

enroute to Hampton Roads and that the vessel would prove more than a match for

the rebel ironclad. A heated discussion followed, with Stanton insisting that

rock-laden steamers be sunk in the Potomac to block the Virginia from reaching the Washington Navy Yard, and he rushed out of the room to send

telegrams to Philadelphia and New York to guard their harbors.

The

news of the Virginia's appearance in Hampton Roads and the destruction of the

warships, Cumberland and Congress, with the loss of

300 men, shocked Lincoln and his cabinet. Edwin Stanton, the Secretary of War,

met with Lincoln at the White House the morning of March 9, and pacing the

Cabinet Room with baleful glances at the men assembled—McClellan, Secretary of

the Navy Gideon Welles, Secretary of State William Seward and others—he almost

shouted in his anxiety that the rebels would destroy the Union fleet, capture

Fort Monroe, and be at Washington before nightfall. "Why, sir, it is not

unlikely that we shall have from one of her guns a cannonball in this room

before we leave it," he had burst out at one point. Welles responded, he

says, to Stanton's hysteria, by saying that the Monitor was

enroute to Hampton Roads and that the vessel would prove more than a match for

the rebel ironclad. A heated discussion followed, with Stanton insisting that

rock-laden steamers be sunk in the Potomac to block the Virginia from reaching the Washington Navy Yard, and he rushed out of the room to send

telegrams to Philadelphia and New York to guard their harbors.

McClellan, after leaving the conference, sent this message to John Dix, commanding at Baltimore:

John A. Dix Washington, March 9, 11:00 a.m.

Virginia sank the Cumberland, the Congress surrendered. Minnesota and St. Lawrence ran aground in approaching scene of battle. At half past eight last night Virginia retired to Craney Island. Please be fully on alert. See that Fort Carroll is in condition of defense in case Virginia should run by Fort Monroe,

George McClellan, Maj.Gen Commanding USA

To John E. Wool, commanding at Fort Monroe, McClellan sent this:

To John Wool Washington, March 9, 1:00 p.m.

If the rebels obtain full command of the water it would seem impossible for you to hold Newport News. You are authorized to evacuate that place, drawing the garrison in upon Fort Monroe which I need not say must be held at all hazards. The performance of the Virginia places a new aspect upon everything and may very probably change my whole plan of campaign, just on the eve of execution.

George McClellan, Maj-Gen Commanding.

And to Edwin Stanton he wrote:

Hon. E. W. Stanton, Sec of War March 9

I think we will find the danger less as we learn more, and am less inclined to think that the Virginia will venture out—nevertheless we must take it for granted that the worst will happen.

McC.

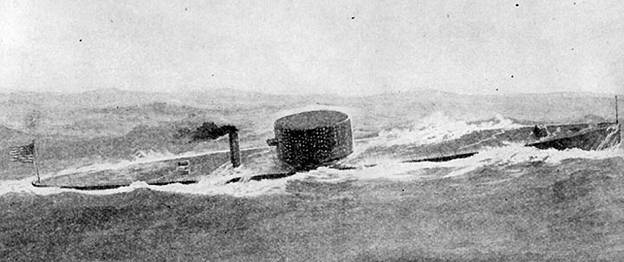

As these messages were going forth the Virginia was indeed venturing forth, and this time she encountered the Monitor standing in her way. When dawn came clear and bright, on March 9, the United States pennant could be seen floating from the Cumberland whose top sail mast appeared above the water, marking the spot where she sank. The Minnesota, badly cut up, lay hard and fast aground, off Fort Monroe and it was evident it was helpless to protect itself. The Congress was gone beneath the waves. As the Virginia approached the Minnesota, it veered around the "Rip Raps," a small man-made island in the main channel of the Road, turned round and came back down on the Minnesota. Then appeared the Monitor abeam the Virginia and opened fire with the two 11-inch guns of her revolving turret, the shots clanging against the Virginia's iron bulwark.

Though the Virginia had more guns, it had lost its smokestack, which inhibited its engine from building steam, and this allowed the Monitor, drawing less feet of water, to come in close and engage the Virginia at point blank range.

Monitor Holds Her Own

The Monitor's captain, John L. Worden, maneuvered to within several feet of the Virginia and concentrated the slow fire of his turret guns in an effort to break in her sides with solid shot. The Virginia, in turn, kept up a rapid fire of broadside, but the only target was the Monitor's turret and her blasts kept missing the vital spot. More than two hours passed as the vessels threw shots and shells at each other, the impacts of the missiles shuttering the iron but neither punching home a vital blow against the other. Worden, at one point, went up into the turret during a lull in the exchange and asked why the guns were not firing. The gun captain replied, "I can do the enemy about as much damage by snapping my fingers every few minutes." Worden then attempted to bring the Monitor directly against the Virginia with the view of boarding her, but the vessel's steering system was inadequate for the task.

The Crews at Work

Bringing the Virginia to full speed her captain, Catesby Jones, tried to ram the Monitor, but Worden turned as the two vessels came in contact and no harm was caused. Again the Monitor came upon the Virginia's side, her bow touching, and fired at point blank range twice, causing the iron plating at the point of impact to buckle. Crewmen of the Virginia came out of a hatchway and made to clamber on board the Monitor, but Worden slipped his vessel quickly astern and opened her batteries upon the open hatchway.

John L. Worden |

Catesby Jones |

Now, tired of the battering, Jones decided to ignore the Monitor and move on to destroy the Minnesota standing aground now in the shoals in front of Newport News. As the Virginia steamed toward it, the Minnesota opened with all her broadside guns. The Virginia responded with its rifled bow gun, sending shells crashing through the frigate into its magazine. This caused an explosion and the ship burst into flames. During this time the Virginia took fifty hits from the Minnesota's guns, sustaining no damage. Then the Monitor came into the scene, interposing herself between the contending vessels, and the Virginia, maneuvering around the Monitor to get a line of fire on the Minnesota, suddenly found herself run aground. After a time, under fire from the Minnesota, Virginia regained the sea and steamed down the bay, with the Monitor trailing her; turning suddenly, Virginia attempted to ram Monitor, but the sleek little vessel dodged away.

At this point, a shot from the Virginia exploded in front of the turret house, throwing hot power into Captain Worden's face, where he had been standing, looking through a slit. Blinded by the blast, Worden turned command over to his executive officer who continued to maneuver the vessel as the Virginia again turned toward the helpless Minnesot. Then, with the tide falling in the Road, the Monitor drew over the middle channel, which the Virginia, because of draft, could not follow, and stood down by Fort Monroe. The falling tide caused Captain Jones to break off the engagement and he steamed the Virginia for Sewell's Point and thence to the dockyard at Norfolk.

Virginia Steams Away

The sea battle between Virginia and Monitor was, tactically, a draw, but from the strategic point of view the edge clearly goes to Virginia. The presence of the Monitor in Hampton Roads gave the wooden war ship fleet some protection against Virginia—it could press Virginia and hound her—but, unless the power of its guns could somehow be increased enough to damage her, the Union gun boats could not get past her into James River.

II

McClellan's Operation Against Richmond Begins

By March 1862, Abraham Lincoln was, according to hearsay reports, in an agitated state. George McClellan had under his command, a fully organized field artillery force of forty-nine batteries totaling two hundred and seventy-four pieces, four regiments of regular cavalry and eighteen regiments of volunteer cavalry, and an infantry force of one hundred and twenty thousand soldiers. Yet, the Confederates were maintaining an army, under General Joseph Johnston, on the Manassas plain and had artillery batteries harassing navigation on the lower Potomac River. The Radical Republicans, in Congress, were harping about the rebel forces' proximity to Washington and McClellan's inaction.

According to the historians and civil war writers, these circumstances explain what Lincoln did next—he stripped McClellan of his status as "general commanding the United States armies," confining the reach of his command to the Army of the Potomac, and imposed upon McClellan a plan of army organization that required the establishment of corps; and then he selected the general officers who were to command them. Not surprisingly, these mandates of Lincoln's did not make George McClellan happy.

Prior to receiving orders from Lincoln detailing his expectations for the operations of the Army of the Potomac, McClellan had made his intentions clear in correspondence with subordinate officers, with his wife, Mary Ellen, and with Lincoln. On March 3, Mac wrote to Halleck, who had requested reinforcements of 50,000 men from the East: "I hope to open the Potomac this week. It will require the movement of the whole army in order to keep Manassas off my back. As soon as I have cleared the Potomac I shall bring here the water transportation now ready and then move by detachments of about 55,000 men for the region of the sandy roads. I expect to find a desperate battle somewhere near Richmond, the most desperate of the war, for I am well assured that Joe Johnston's army at Manassas remains intact, and that it is composed of the best armed and best disciplined that the rebels have."

Note: This theme of fighting "a desperate battle, the most desperate of the war," recurs again and again in McClellan's writings addressed to third-parties, but when the decisive moment came to plunge into it, the record will show that McClellan shied away from it.

No doubt aware that McClellan was, in fact, calling his forces to attention, ready now to move them out to confront the rebel force at Manassas, clear the Potomac of the rebel batteries, and then proceed via the Chesapeake Bay to Fort Monroe, to begin the approach to Richmond, Lincoln, using his constitutional status as "Commander-in-Chief," issued several military orders. The first of these—President's War Order No. 2—issued on March 8th as the Virginia was sinking the Union warships in Hampton Roads, reads, in pertinent part:

1. The Major General commanding the Army of the Potomac will proceed forthwith to organize the army into four Army corps to be commanded according to seniority of rank as follows:

First Corps, to consist of four divisions and to be commanded by Major General Irwin McDowell.

Second Corps, to consist of three divisions and to be commanded by Brigadier General E.V. Sumner.

Third Corps, to consist of three divisions and to be commanded by Brigadier General Heintzelman.

Fourth Corps, to consist of three divisions, and to be commanded by Brigadier General E.D. Keyes.

2. The forces left for the defense of Washington will be placed in command of Brigadier General James Wadsworth.

3. A fifth army corps, to be commanded by Major General Nathaniel Banks will be formed with his own division (now under Williams) and General Shields's division. (To this corps was briefly attached Sedgwick's division.)

Note: As Lincoln wrote it, the memorandum leaves the impression that the fifth corps, under Nathaniel Banks, was a unit independent of the "Army of the Potomac," which, the memo specifies, constitutes McClellan's command; yet, the record shows that McClellan issued orders to Banks, designating the sector in which the corps was to operate, and there are no writings of Lincoln's, written at this time, contradicting McClellan's assertion of command over Banks. Therefore, it seems clear that, in fact, Lincoln intended Banks's corps to be part of McClellan's command, but to remain in the northern sector of McClellan's "Department." Lincoln envisioned then, at the outset, two departments: Fremont's and McClellan's, covering the line from Wheeling to Washington.

On the same day, Lincoln issued his "War order No 3:

Ordered, that no change of the base of the operations of the Army of the Potomac shall be made without leaving in, and about Washington, such a force as, in the opinion of General McClellan, and the commanders of all the Army corps, shall leave said City entirely secure.

That any given movement enroute for a new base of operations shall begin to move upon Chesapeake Bay as early as March 18th

Lincoln's orders are not inherently defective, but they do demonstrate clearly the estrangement that existed at that time between himself and his top general in the East. McClellan was supposed to be—he certainly should have been—Lincoln's primary military advisor. But, for some months, so the historians say, he had been secretive and apparently not particularly courteous in his dealings with Lincoln. A reasonable man in Lincoln's shoes might well have developed as a result, feelings of distain toward McClellan; but more than that, the plain fact that McClellan was a dyed-in-the-wool Democrat made the relationship between the two men as incompatible as water and oil.

In his Own Story, published posthumously, in 1885, McClellan's political leaning is set forth:

"The Radical leaders saw clearly that it would not be possible to make a party tool of me, and soon concluded to ruin me if possible. It had been clearly stated by the Congress and the Government that the sole object of the war was the preservation of the Union. We fought to keep the South in the Union, and the practically unanimous sentiment of the army, as well as of the mass of the people, was at that time strongly in favor of confining the war to that subject. The real object of the Radical leaders was not the restoration of the Union, but the permanent ascendancy of their party, and to this they were ready to sacrifice the Union, if necessary. They knew that if I achieved military success my influence would be necessarily very great throughout the country." (Emphasis added.)

And to his wife, Mary Ellen, on March 11, he wrote of his feelings toward the "Radical leaders," which must include Lincoln.

"I regret that the rascals are after me again. I had been foolish enough to hope that when I went into the field they would give me some rest, but it seems otherwise. Perhaps I should have expected it. If I can get out of this scrape you will never catch me in the power of such a set again—the idea of persecuting a man behind his back."

Given the attitude of each of these gentlemen toward the other, taking into account the animosity and discord between them, Lincoln should not have proceeded with McClellan as the general commanding his main army, especially when that army was about to set off on an operation that would, if successful, probably result in knocking Virginia out of the war.

The Strategic Situation, March 1862

With the Union successes in the West, in Missouri, Kentucky, and Tennessee, it was plain to see that Halleck's armies were about to sweep these States clean of the enemy and march into the upper reaches of Arkansas, Mississippi and Alabama. When this happened, the Confederacy's defensible western border would be shrunk to the lower reaches of the Gulf States, leaving only the Confederate heartland of Georgia and the interior of the Carolinas safe from immediate enemy penetration. Everything, then, would plainly depend on the Confederate army in Virginia keeping the enemy north of the Rappahannock River: for without the eastern barrier to the Confederate heartland that Virginia provided, the war would be quickly lost.

But what other option, but McClellan to lead the Army of the Potomac, did Lincoln have? Of the four army corps commanders, of his selection, Irvin McDowell was the senior regular army brigadier and the logical choice to replace McClellan at this crucial moment. McDowell had, it seems, Salmon Chase as a friend in the Cabinet. He had commanded the first army Lincoln had been able to get into the field, and he had done a reasonably good job, given the tactical restraints imposed by Lincoln, fighting the army at the Battle of Bull Run. He lost the battle, it is true, and his army of inexperienced volunteers had disintegrated at the end, but only because Beauregard's force had been timely reinforced by Joe Johnston's. It was no fault of McDowell that Robert Patterson, commanding four divisions of Pennsylvania volunteers, had failed to keep Johnston engaged in the Shenandoah Valley long enough to allow McDowell to fight the battle with Beauregard alone. It was Patterson's failure to keep pace with Johnston, not McDowell's management of the battle, that was responsible for the Confederate win and the Union loss. Lincoln had gotten along with McDowell well enough and McDowell, unlike McClellan, was not a rally point for the Democrats squirming for a way to build themselves back into power.

At this moment in time Abraham Lincoln, regardless of what the historians claim, was in an excellent position to end the war immediately. He now had Henry Halleck, in the West, controlling all the Union forces west of the Appalachian Mountains, pressing the undermanned Confederate army, under Sidney Johnston, back from the southern border of Tennessee, with the future pointing to an operation against Vicksburg—to open the Mississippi River to New Orleans—and an operation into east Tennessee to capture Chattanooga and move then toward Atlanta. If he could just push the enemy away from Richmond, he would gain access to the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad, as well as the other railroads descending into the Carolinas from Petersburg, and could then move toward Atlanta from the East. Under the pressure of this closing pincer movement, supported by the full force of the Union armies, with the immense wealth of the North behind them, the heartland of the Confederacy could not possibly survive for long.

Given these facts, it must be said then that, but for something unique to McClellan's situation at that time, Lincoln certainly would have dumped McClellan as army commander and replaced him with McDowell. The only explanation for why he did not, seems reasonably to be the fact that Little Mac was extremely popular with the soldiers in the ranks—soldiers as McClellan pointed out in his Own Story who felt strongly they were putting their lives on the line, for the Union; and not for African Negro slaves. Dumping McClellan at this moment in time, given what was being simultaneously debated vehemently in Congress, would have been perceived by the soldiers (and their families at home) as directly the result of the Radical Republicans' agenda of freeing the slaves. So Lincoln choose to try and hold the rudder steady as it was.

But, having made the decision to leave McClellan in executive control of the Army of the Potomac, Lincoln ought not then to have interfered with Mac's execution of the agreed upon plan of operations. At the very least, given Lincoln's war order, Mac had the right to expect to arrive on the Yorktown peninsula with thirteen infantry divisions, aggregating at least one hundred and forty thousand soldiers present for duty. But he arrived there with ninety three thousand, Lincoln having stripped his army of five divisions for a stupid reason. This happened because Lincoln took it in his head—no doubt under extreme political pressure from the Radicals—to find John C. Fremont, who he had dumped from the command of the Department of Missouri, a new occupation.

On Sunday, March 9, as the Virginia and Monitor were bouncing cannon balls off their iron sides, word came to Washington that the Confederate army at Manassas was gone. McClellan rode out to Fairfax Courthouse where he set up his headquarters camp, followed the next day by the march of the army corps from Alexandria. The fact that the rebel army had withdrawn from Manassas came as no surprise to McClellan. For weeks he had been receiving intelligence that, as soon as the roads became hard enough to handle the traffic of artillery and wagons, the place would be abandoned, for a safer position behind the Rappahannock River. Mac saw no point in pursuing the enemy to the Rappahannock, because he meant to put the army aboard steamers and move it down the Potomac to Chesapeake Bay. Once word came to him that the Monitor had held her own against the Virginia, keeping the rebel ram away from the remaining ships of the fleet, he decided upon Fort Monroe as the army's staging area and the movement commenced.

A day later came another of Lincoln's war orders; this one informing Mac that, having taken the field in command of the Army of the Potomac, Lincoln was relieving him from command of the other military departments. Henceforth, at least for a time, Lincoln would try his hand at issuing military movement orders directly to the field generals; a task made somewhat easy by the fact that, at about the same time, he had raised Henry Halleck to supreme command of the territory west of the Appalachians, and Halleck was proving himself well capable of moving the masses of Union infantry to the strategic objectives without any prodding from Lincoln.

The first of these movement orders hit Mac in the solar plexus and made him sputter. On the 13th of March, McClellan had met in council with his corps commanders and they came to an agreement which, reduced to writing, was sent to the President. The memorandum specified that, the enemy having retreated from Manassas to Gordonsville, the Army of the Potomac would carry on its operations from Old Point Comfort, between the York and James Rivers, provided:

1. That the enemy's vessel, Virginia, can be neutralized.

2. That the means of transportation is ready.

3. That a naval force can silence the enemy's batteries on York River.

4. That the force to be left to cover Washington shall be such as to give Lincoln an "entire feeling of security for its safety."

Note: Lincoln has written, "in and around Washington."

The same day, Secretary of War Stanton wired McClellan, Lincoln's reply.

1. Leave such force at Manassas as shall make it "entirely certain that the enemy shall not repossess himself of that position and line of communication."

2. Leave Washington "entirely secure."

3. Move the remainder of the force down the Potomac, choosing a new base at Fort Monroe, and pursue the enemy at once.

Hampton Roads: as long as Virginia can operate James River is Blocked.

McClellan then issued orders in compliance with Lincoln's requirements, at least so he thought. To Nathaniel Banks, the "Bobbin Boy" of Massachusetts, who then, with the Fifth Corps, was at Winchester in the Shenandoah Valley, went these instructions:

1. You will entrench your command at Manassas, and rebuild the Orange & Alexandria Railroad from Washington to Manassas, and the Manassas Gap Railroad to Strasburg in the Shenandoah Valley.

2. As soon as you have the Gap Railroad running, place a brigade of infantry at the point the road crosses the Shenandoah River (Front Royal), and send cavalry regiments to Winchester and scout the upper valley, paying attention to Chester's Gap in the Blue Ridge.

3. Place a regiment at Warrenton and at the railroad bridge over the Rappahannock south of that place.

4. The general idea is to cover the line of the Potomac and Washington.

Note: Lincoln's general idea, whether expressed or not at this time, was to cover the line from Wheeling, on the Ohio River, to Romney, to Winchester to Manassas, to Washington.

To James Wadsworth, whose force consisted of thirty-seven volunteer regiments, plus seven artillery batteries, and about 4,000 cavalrymen, went these orders:

1. Banks will command at Manassas with two divisions, Williams and Shields, and you will command the forts around Washington with the troops shown on the list attached.

2. As new troops arrive in Washington, you will form them into brigades, promote their training and discipline and facilitate their equipment.

The Key, here, is Fremont's role in Lincoln's mind.

Then, on March 31, as Mac was going on board a steamer to go down to Fort Monroe, most of his army having by now preceded him, he received from Lincoln the first of several disappointing communications.

Executive Mansion, Washington, March 31

Maj Gen McClellan:

My dear sir: This morning I felt constrained to order Blenker's division to Fremont; and I write this to assure you that I did so with great pain, understanding you would wish it otherwise. If you could know the full pressure of the case I am confident that you would justify it, even beyond a mere acknowledgement that the commander-in-chief may order what he pleases.

Yours Truly, A. Lincoln

Yes, indeed, you may, but is it wise? At this time President Lincoln had on his plate two grand operations, each involving over one hundred thousand soldiers, concentrating against two strategic points: Corinth, Mississippi, a crossroads where the major north/south and east/west railroads in the western theater came together, and Richmond, the base of operations for the rebel army in the East. In the West, by this time, Lincoln had no problem unifying army command under one general, Henry Halleck, and allowing him to concentrate all the military forces in the West for an attack on Corinth, which brought together at one place Grant's, Buell's, and John Pope's armies, giving Halleck an aggregrate force of about 127,000 men. Yet, in the East, at the every moment he has released McClellan to move the Army of the Potomac 100 miles south, to lay siege to the Confederate Capitol, he strips McClellan's siege army of almost 10,000 men and sends them off where, to do what?

Lincoln's Fixation on East Tennessee

For months Lincoln had been pushing McClellan, and McClellan for his own reasons was a willing supplicant in this instance, to get Carlos Buell, who had almost 80,000 men under his command, to move to occupy Knoxville, Tennessee. Without question, east Tennessee was filled with Union men who were as rebellious against the authority of the Confederate Government as the citizens of North Missouri were rebellious against the authority of Lincoln's Government. Lincoln quite naturally wished to get a force into that region in order to support the Union rebellion, but Buell, intelligently recognizing this was not possible—there was no way to support the movement of a large force that far, no railroads, no hard roads, no rivers—concentrated instead on moving in the direction of Bowling Green, Kentucky, using the railroad between Louisville and Nashville to support the movement of his army.

So, after the Kentucky Line had collasped and Nashville had been occupied, and as McClellan was taking the field, Lincoln changed the department arrangement to give Halleck full control of Buell's force, in his push to seize Corinth. But, at the same time, quite unreasonably, given the circumstances, Lincoln did not give up on his idea of getting a force to Knoxville.

To gain that point, he set up the Mountain Department—the territory bounded by the reaches of the Appalachians—and, under pressure from the Radicals, assigned command of it to John C. Fremont, an incredible choice given Fremont's demonstrated incompetence in Missouri. According to the renowned historian Alvin Nevins's view of things, "Lincoln believed it feasible to march from western Virginia through the Appalachian Mountains into East Tennessee and seize the railroad at Knoxville, rescuing the Unionists of that region." If this was, in fact, Lincoln's purpose in building up a force, under Fremont's command, taking a division of infantry from McClellan to do it, he was being ridiculous.

On March 22, Lorenzo Thomas, the Army Adjutant General, no doubt at the behest of Lincoln, wired Fremont this:

WAR DEPARTMENT

Washington, March 22, 1862

Maj. Gen John C. Fremont, USA, commanding Mountain Department

Sir: Your attention will be directed to the railroad between Knoxville and Richmond, some one point of which within your command you will seize and hold with the troops under your command. You will enter without delay upon your command and lose no time in commencing active operations.

By order of the Secretary of War:

L. Thomas, Adjutant General

Under Lincoln's orders, arriving at Wheeling on March 22, Fremont formally assumed command of the Mountain Department on March 29. The next day, demanding that Lincoln give him Blenker's division, Fremont set forth his initial plan of campaign in a letter to Washington.

HON. E.M. STANTON, secretary of War March 30, 1862

Assuming it is the desire of the Government that the first object shall be to take possession of the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad, the army corps should march through the open land of Kentucky and East Tennessee directly upon Cumberland Gap or Knoxville, and so turn the position which the enemy may have assumed in the mountain defiles. It will be therefore necessary to concentrate troops at Nicholsville, Kentucky, a point having railroad connections with Louisville. The roads from there to Knoxville are good.

J.C. Fremont

|

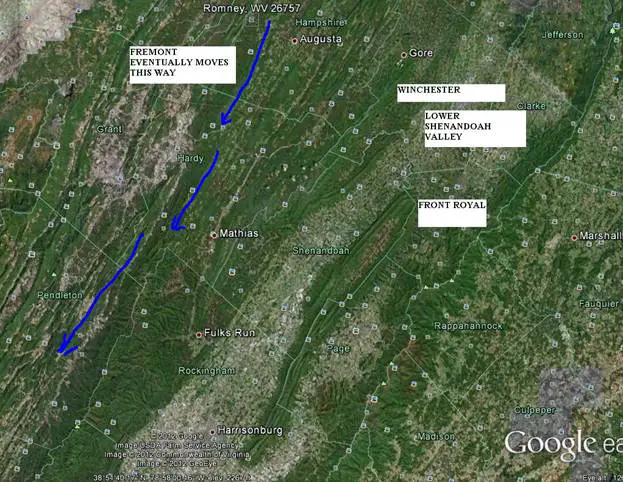

Fremont's Eventual Move South Through The Alleghanies

As Union general, Jacob D. Cox, who operated in this area under Fremont's command, put it: "The plan would have failed, first, from the impossibility of supplying the army on the route, as it would have been without any reliable base of operations; and, second, because the railroads east of the mountains ran on routes well adapted to enable the enemy quickly to concentrate any needed force at Staunton and Lynchburg to overpower the column." It is just incredible that, at this crucial moment, Lincoln would commit 20,000 Union troops to a silly and impossible endeavor when those troops would make the difference between McClellan's success or failure in his operation against Richmond.

Fremont's role should have been to control the Shenandoah Valley,

Leaving Banks to control the Manassas Plain.

In compliance with Stanton's request for information of his movement plan, Fremont wired him on March 30 a list of troops presently within his command. These totaled 21,000 men. Of these, Fremont stated he meant to use for "active operations" Blenker's, Schenck's, and Cox's divisions, plus Milroy's brigade. Eventually he would be reinforced with a division of troops under Franz Sigel, another of Fremont's cast-off cronies.

Soon it will become plain that Lincoln is attempting to do too much and that McClellan will pay the price. Lincoln has Halleck's forces, including Buell's army, concentrating for an advance against Corinth, and he has a detachment from Buell's army, Garfield's command, moving toward Cumberland Gap. General Rosecrans, with several thousands of men, is at Wheeling, in position to cooperate with Garfield in this endeavor. In this configuration, Fremont's base of operations clearly belongs at Winchester, to guard the lower Shenandoah Valley from Stonewall Jackson's intrusions. But, instead of assigning Fremont this role, Lincoln made the conscious decision to build up the force at Wheeling, with Fremont in command, in order to move through the Appalachian range to reach the Tennessee & Virginia Railroad.

Yet, at the same time, Lincoln knows that McClellan's plan includes the movement of Banks's Fifth Corps from the Shenandoah Valley to the Manassas plain as the means of making it impossible for the enemy to occupy Manassas—and so threaten Washington directly—thus meeting Lincoln's requirement that Washington "be entirely secure."

It seems from the record that Lincoln therefore expected Fremont to be responsible for keeping the Shenandoah Valley clear of Stonewall, as he had designed Fremont's "Mountain Department" to include the lower Shenandoah Valley as far as Moorefield, in Hardin County, which was to be guarded by one of Fremont's divisions, Robert Schenck's. This fact is clear from Stanton's correspondence with Fremont at this time.

WAR DEPARTMENT, Washington, March 28, 1862

Major-General Fremont, commanding Mountain Department

The events at Winchester since you left Washington require that immediate attention should be given to the condition of your forces at Cumberland and along the line of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. Cooperation with the forces in McClellan's department, continguous to yours, may be very essential. Romney should be held by adequate force and Moorfield should be occupied.

EDWIN STANTON, Secretary of War

The Shenandoah Valley

The

"events at Winchester" Stanton refers to, relate to the reality that

Stonewall Jackson, with three brigades of infantry, totaling 3,700 men, has

been operating in the Shenandoah Valley threatening Winchester and the line of

the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad for months; advancing and retreating as the

divisions of Banks's corps occupied and then abandoned Winchester.

The

"events at Winchester" Stanton refers to, relate to the reality that

Stonewall Jackson, with three brigades of infantry, totaling 3,700 men, has

been operating in the Shenandoah Valley threatening Winchester and the line of

the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad for months; advancing and retreating as the

divisions of Banks's corps occupied and then abandoned Winchester.

Between the time the Virginia and Monitor had their engagement in Hampton Roads and the time that McClellan moved his headquarters to Fairfax Courthouse as the Confederate army at Manassas fell back, Stonewall Jackson's small division was occupying Winchester. To drive him away, McClellan had Banks advance Shields's division up the valley to Strasburg, forcing Jackson to fall back about 18 miles to Mount Jackson, a point midway Harrisonburg and Strasburg.

Lincoln apparently expected, as he worked up his paper plan, that, as Banks pulled his forces out of the valley and onto the Manassas plain, Fremont would promptly have his forces, totaling about 21,000 men, fill the void. How Lincoln expected Fremont to do this, while at the same time marching several hundred miles to Knoxville defies rational explanation.

In Lincoln's mind, it's plain to see, a line was drawn from Halleck's concentration point at Shiloh, east to Washington, with Fremont and Banks covering the line between Wheeling, Romney, Winchester and Manassas. His miscalculation in this regard will result in his hamstringing McClellan's operation against Richmond. The fault, then, for McClellan's failure—to a point—must rest entirely with Abraham Lincoln

That Confederate President Jefferson Davis understood the importance of McClellan's movement to the Yorktown peninsula is clear from the Rebellion Record:

RICHMOND, February 28, 1862

General Joseph E. Johnston, commanding department

Sir: Your opinion that your position at Manassas may be turned whenever the enemy shall choose to advance, so clearly indicates prompt effort to disencumber yourself of everything which would interfere with your rapid movement when necessary. The Commissary General had previously stopped further shipments to your army. With your present force, you cannot secure your communication from the enemy, and may at any time, when he can pass to your rear by Brentsville, be compelled to retreat at the sacrifice of your train and army stores, and without any preparation on a second line to receive your army as it retired.

Threatened as we are by a large force on the southeast (Burnside) you must see the danger, should we be beaten on the lines south and east of Richmond; and that reflection is connected with consideration of the fatal effect which the loss of Richmond would have upon the cause of the Confederacy.

Two questions therefore press upon us for solution. First, how can your army best serve to prevent the advance of the enemy while the want of force compels you to stand on the defensive? Second, what dispositions can you make to enable you most promptly to cooperate with other columns, in the event of danger to the capital?

I need not urge on you the value to our country of arms and munitions of war. You know the difficulty with which we have obtained our present small supply. We need you to save the heavy guns at Manassas as they will be needed for the defense of this city.

The letter of General Jackson presents the danger with which he is threatened and the force he requires to meet it. I have not the force to send, and have no other hope of his reenforcement than by the militia of the valley. Anxious to hold and defend the valley, that object must be pursued as to avoid the sacrifice of Jackson's army or the loss of the arms in use there.

As has been my custom, I have only sought to present general purposes and views. I rely upon your special knowledge and high ability to effect whatever is practicable in this our hour of need. The military paradox, that impossibilities must be rendered possible, had never better occasion for its application.

Very truly yours and respectfully, yours.

JEFFERSON DAVIS

How different, here, from Lincoln's, is the tone of the President's communication with his most important general operating in the field.

Note: At this time Johnston's army at Manassas amounted to 40,000 men. This is the same amount Sidney Johnston have at hand to prevent Hallick's horde from reaching Corinth.

II

General Lee Comes Home To Richmond

Just, then, in the middle of March, as Johnston was falling back from Manassas, and Jackson was falling back from Winchester, in the face of the advance of the enemy's masses, President Davis called General Lee to Richmond from Charleston, and soon after his arrival at the Capital the following order was issued.

GENERAL ORDERS, NO 14 ADJUTANT GENERAL'S OFFICE

Richmond, March 13, 1862

General Robert E. Lee is assigned to duty at the seat of government; and under the direction of the President, is charged with the conduct of military operations in the armies of the Confederacy.

By command of the Scretary of War: S. Cooper, adjutant General

At the same time President Lincoln is dumping McClellan as the general charged to conduct the military operations of the Union armies, President Davis is reaching out to Lee.

When General Lee arrived in Richmond and assumed his new duties, the military situation was grim. The Confederate Government, like the Lincoln Government, had had one year to mobilize the country's resources, getting armies of armed men into the field in sufficient numbers to successfully resist, if not overwhelm, the forces the enemy brought against it. But the Confederate Government had fallen far short in the endeavor: The Gulf States, including Tennessee, Arkansas, and Missouri, had produced only about half the number of men that Lincoln's Government had produced from Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Michigan, Wisconsin, Iowa, Nebraska, and Kentucky and Missouri. Of this number of Confederates, at least 20% of the men were without any arms and most of the remainder were using their farm rifles as weapons of war. The same result fell to the East: In Virginia, there were less than half the numbers available, compared to the numbers in Union uniform, to resist Lincoln's invasion.

At this time, too, Union gunboats were navigating the York River, approaching the mouth of the Pampunkey River where the York River Railroad begins its run toward Richmond at the White House, McClellan's first troops were arriving in transport at Hampton Roads, and Nathaniel Banks's corps was occupying Winchester in the Shenandoah Valley, with its advance division, under James Shields, an Illinois politician, covering the valley turnpike at Strasburg on the line of the Manassas Gap Railroad. Rosecrans was at Wheeling and Fremont was on his way to join him.

The Shenandoah Valley

General Lee set to work, making sense of the troop deployments available to meet the contingency everyone knew was coming, sorting out the confusion that existed among the various departments of supply, assisting in the transition from one secretary of war, Judah Benjamin, to another, William Randolph; and, finally, taking charge of the mustering of 30,000 young Virginians just drafted into the service of the Confederate Army. They were coming to defend their country, and their lives were in his hands.

IV

Stonewall Takes the Initiative

|

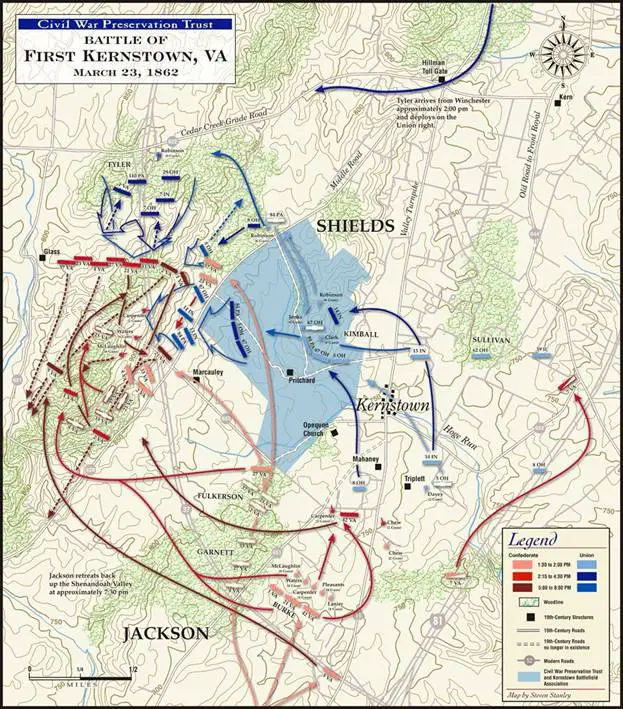

On March 20, Shield's and Williams's divisions of Banks's corps—the one from Strasburg and the other from Winchester—began to march east, to cross the Shenandoah River and pass out of the Shenandoah Valley to take up their assigned positions east of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Joe Johnston's army now was behind the Rapidan River, near Gordonsville, with a detached force, under Holmes, occupying Fredericksburg, waiting for McClellan's objective point to become clear as his army corps were moving toward Alexandria. That night, Turner Ashby, the dark cavalier, brought word of this to Jackson, who was then camped near Woodstock.

Jackson immediately ordered the camp broken up and put his division to marching north on the valley pike, and the night of the 23rd, after marches of 18 and 22 miles, he reached Strasburg. The next day he marched on toward Winchester, arriving in the suburbs at Kernstown about noon. As he arrived Ashby's cavalry was falling back in the front of one of Shields's brigades supported by two artillery batteries. Jackson thought this brigade to be the last of Shields's division, the rest he thought had marched to Berryville, to cross the Shenandoah River and pass to Manassas through the Blue Ridge. |

The Union front extended on both sides of the valley pike: on the right the line ran over a broad expanse of rolling grassland and on the left it occupied a knoll, crowned with a clump of trees. Looming slightly behind the front was a long ridge covered with dense woods behind which lies Winchester. Not having men enough to advance across the rolling grassland, Jackson decided to attempt to seize the wooded ridge on his left, the idea being to force the defenders to improvise a new position to counter his attack. Hesitation and confusion might ensue, giving Jackson's force a chance to turn the enemy's flank and induce them to fall back into Winchester.

The rebels get to the wall first.

As one of Jackson's biographers tells the story, the rebel infantry, about 2,000 in number, the rest having not yet come up, crossed fences, marshy ground, running through a sheaf of shells thrown at them from the knoll, reached the wooded ridge and began to press eastward to get behind the Union front. Suddenly, there was heard a great crashing volley of rifle fire, and a mass of blue emerged from a woods farther to the north and thronged up the ridge against the 21st and 27th Virginia regiments, the men of which ran forward to a stone wall and returned fire full in the face of the Union men. A heavy fire, at the closest range, blazed out in the face of the charging men and in a few moments the approach to the wall was littered with dead and wounded men. A Pennsylvania regiment, leaving a color on the field, gave way in panic and a mad blue rush commenced to reach again the protection of the woods. Still, more and more blue coats appeared in masses, though; advancing, falling back, advancing again against the thin gray line that held the ridge, until, finally, after two hours of fighting, with dusk falling, Jackson ordered the retreat, realizing by this time that he was engaged with fully 9,000 men of Shields's division.

Shields,

an able officer, who had commanded a brigade in Mexico, had learned from previous

experience with Jackson how aggressive he was and, anticipating that he would

be eager to attack, had ordered the greater part of his division, which had

countermarched as he advanced, to remain concealed. Only after his lead brigade

had grappled with Jackson and had him fixed in a fight, did Shields feed the

main body of his division into the battle, breaking Jackson's back.

Shields,

an able officer, who had commanded a brigade in Mexico, had learned from previous

experience with Jackson how aggressive he was and, anticipating that he would

be eager to attack, had ordered the greater part of his division, which had

countermarched as he advanced, to remain concealed. Only after his lead brigade

had grappled with Jackson and had him fixed in a fight, did Shields feed the

main body of his division into the battle, breaking Jackson's back.

Jackson was watching the progress of the battle,when, suddenly, to his astonishment, he saw the lines of his old brigade falter and fall back. Galloping to the spot he shouted orders, "Stop, hold your front!" Seizing a drummer by the shoulder, he dragged him to a rise of ground, in full view of the troops, and screamed, "Beat the rally!" The drum rolled at this, and with his hand on the trembling boy's shoulder, amidst a storm of sipping bullets, he tried to check the flight of his defeated troops. He looked in vain for Garnett to come up, but his lines were shattering, it was too late, the men were running, it was impossible to stay the rout.

Wildly upset, Jackson left the field shouting orders as he passed through the ranks of the men; getting two fresh regiments—the 5th and 42d Virginia regiments—into compact lines of battle on either side of the pike; putting batteries into action on their flanks as his men passed up the road toward Strasburg. On came against this front, the 5th Ohio, 84th Pennsylvania, and 14th Indiana regiments, and Jackson's second line was compelled to give way. Again the heavy volleys blazed fire and coughed long strings of blue smoke and the sound of whizzing bullets filled the air. Jackson's men fell back three miles to where their trains were parked, utterly worn out, famished, thirsty, many wounded; they had reached the limit of their endurance, the fierce three hours of fighting had left them panting for breath, desperate for a cup of water. Yet they were proud to be Jackson's hard core.

Jackson, when the last sounds of battle died away, followed his troops.

At the War Department in Richmond, sitting at a desk stacked with papers in a cubby-hole of a room, General Lee studied the reports coming in about Jackson's movement and the ensuing battle and knew he had found a soldier that saw eye to eye with him, the necessity to try and make impossibilities possible.

II

The War In The West March 1862

Credits

Civil War Trust

Don Troiana

Images

Source Materials

The Official Records of the Rebellion, volumes 5 and 11.

Colonel G.F. Henderson, Stonewall Jackson and the American Civil War 1919 Longmans, Green & Co.

George McCellan, McClellan's Own Story 1885 Charles L. Webster & Co.

Allan Nevins, Fremont, Pathfinder of the West 1939 University of Nebraska Press

Admiral David D. Porter, The Naval History of the Civil War 1886 The Sherman Publishing Co.

James G. Hollandsworth, Jr., Pretense of Glory: The Life of General Nathaniel Banks 1998 Lousiana State University Press

Battles and Leaders, Vol. 2

Robert W. Winston, Robert E. Lee 1934 Grosset & Dunlap

| Read all the Civil War Sesquicentennial articles | Comments and Questions to the Author |

|

Joe Ryan Original Works @ AmericanCivilWar.com Joe Ryan Video Battlewalks |

|

| About the author: Joe Ryan is a Los Angeles trial lawyer who has traveled the route of the Army of Northern Virginia, from Richmond to Gettysburg, several times. |

||

Battle of Gettysburg

General Robert E. Lee

General JEB Stuart

General Jubal Early

Confederate Commanders

General Joseph Hooker

Union Generals

American Civil War Exhibits

State Battle Maps

Civil War Timeline

Women in the Civil War