| Read all the Civil War Sesquicentennial articles | Comments and Questions to the Author |

What Happened In March 1862

II

The War in the West

| What Happened in March 1862 |

Henry Halleck Plans a Campaign

|

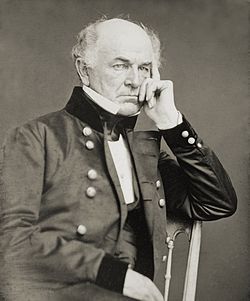

Major-General Henry W. Halleck came to the Civil War, a West Point graduate, a published author of highly acclaimed military studies, a successful army officer, lawyer and businessman who gained high reputation and considerable wealth for himself in California. But he is generally dismissed by the historians and civil war writers as a pompous, slow-witted army administrator who contributed nothing substantial to the progress of Union arms. In fact, Halleck contributed a great deal to the success of Union arms, at least up to the point he replaced McClellan as Lincoln's "general-in-chief," in July 1862. And the fault for his failure as general-in-chief must lie more with Lincoln than himself. |

On November 19, 1861, Henry Halleck was assigned command of the Department of Missouri, which now included the territory of Arkansas as well as that part of Kentucky that lies between the Mississippi and Tennessee rivers.

The Strategic Situation When Halleck Arrived at St. Louis

Halleck had been preceded in command of the Department by three Union commanders—William S. Harney, Nathaniel Lyons, and John C. Fremont; a fourth commander—David Hunter—held the position for two weeks, pending the arrival of Halleck after Lincoln fired Fremont. Halleck's assignment was to bring Missouri finally and firmly into the Union camp, and then to organize a movement to open the Mississippi as far southward as Memphis.

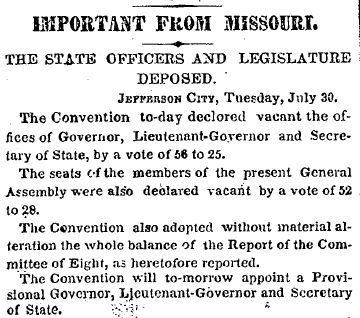

At the outbreak of the war, in April 1861, the government of Missouri, located at Jefferson City in the center of the State, had collapsed, with the governor, Claiborne Jackson, most of the Legislature, and the State's Militia, under General Sterling Price, taking up the Confederate cause. (Most of Missouri, outside the limits of Saint Louis, was Confederate in sympathy but sparsely populated.) This event led the section of the State north of the Missouri River into a classic condition of guerilla warfare, with Confederate sympathizers roaming the countryside killing Union sympathizers, looting Union households, and destroying railroad bridges. Sterling Price, in conjunction with Ben McCulloch, who arrived with reinforcements from Arkansas, roamed the southwestern sector of the state between Lexington and Springfield; and Confederate forces from Tennessee appeared in the later stages of this period at New Madrid, in the southeastern corner of the State, and roamed between that point and Ironton.

!861-1862 Railroad Net In Missouri

Shortly after Lincoln's first call for volunteers, in April 1861, Francis Blair, Jr., a member of Congress and the leader of the Union party in St. Louis, in cooperation with Nathaniel Lyon, organized an armed body of men who took control of the arsenal in the city and drove the Confederates beyond the city limits to the west. For the period immediately following this—essentially the three month volunteers' period of enlistment—William S. Harney, a career Army officer of Southern background, acted as department commander. Harney was inclined to maintain the peace by negotiation with Missouri Governor Jackson and Sterling Price and this caused him to fall into violent political clashing with Blair. This in turn threw Missouri's political and military affairs into such wild confusion, that Lincoln—with the Blair family's prodding—replaced Harney with John C. Fremont.

In the interval between Harney's dismissal and Fremont's arrival in St. Louis, Nathaniel Lyon, taking command of the Union force of Missouri volunteers, and using the railroad head at Rolla as his base, proceeded to move toward Springfield to engage Price and McCullough. Accompanying Lyon, in command of a column, was Franz Sigel, a German immigrant who was very important to Lincoln's effort to enlist troops from the German population of St. Louis, but a combat officer who would prove himself deficient in several respects. This movement eventually turned out badly, when Lyon was killed in battle at Springfield just as Fremont was establishing his department headquarters at St. Louis.

|

Fremont was a career army officer who had gained a national reputation publishing a book about his explorations through the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Coast. This, along with his public expression of views regarding slavery, led, in turn, to his nomination as presidential candidate of the Republican Party, in 1856. (By 1856, Fremont had resigned from the army and was operating a mining venture in California.) Appointed by Lincoln as one of four major-generals in the Regular Army while he was in Europe on business, Fremont returned to the United States in June 1861, visited with Lincoln at the White House, spent some time in New York, and then took train to St. Louis, arriving there on July 25, several days after Lyon was killed at Springfield. |

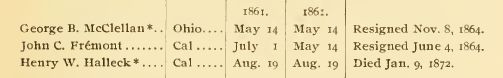

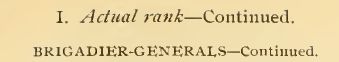

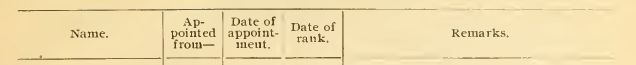

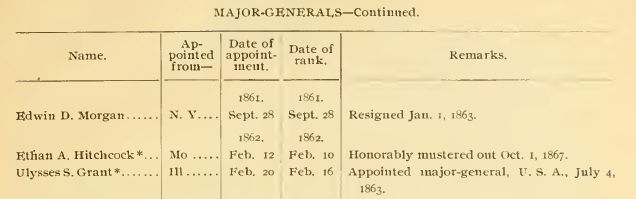

Dates of Appt. and Rank, Regular Army Major-Generals, 1861

(Memorandum Relative to General Officers, War Dept. 1906)

*graduate of West Point

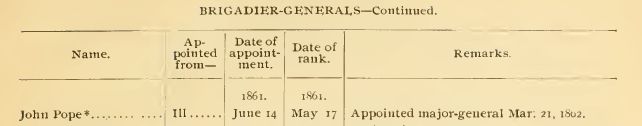

Dates of Appt. and Rank, Regular Army Brigadier-Generals, 1861

(Same source)

Sterling Price |

Ben McCulloch |

Franz Sigel |

Nathaniel Lyons |

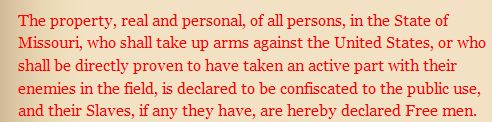

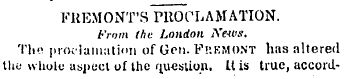

Thirty-five days after his arrival, on August 30, Fremont issued his famous proclamation, declaring that he was taking the State Government's administrative powers to himself, placing the State under martial law, and announcing that the slaves of all persons proven to be rebels in military trials would be freemen. Fremont's declaration was the first public admission that as far as the Republican Party was concerned the object of the war was to free the slaves by force. Fremont proclaimed:

Fremont published his proclamation, knowing that its terms exceeded in scope the authority for confiscation that the Congress of the United States had established as law, twenty days before.

Congressional Act of August 6, 1861

"Sec 4: Whenever hereafter, during the present insurrection against the Government of the United States, any person claimed to be held to labor under the law of any state, shall be required to take up arms against the United States or to be employed upon any fortification, the right of the person owning him shall be forfeit, and whenever the owner shall seek to enforce his claim to such labor, it shall be a full defense against the claim that the person bound to labor was forced to labor against the United States."

The only practical difference between Fremont's proclamation and the law of Congress was that, under Fremont's scheme, the factual basis for confiscation was to be proven in a military tribunal under the law of war (the method the 2000-2011 Congress has adopted for its "war on terror"), while, under the 1861 Congress's scheme, the factual basis was to be established in a federal court. Notwithstanding that this important difference did not change the issue to be decided—was the defendant guilty of the offense charged—the public's perception of what was the object of the war immediately changed, and a wave of political hysteria engulfed the people of the border States, especially in Kentucky.

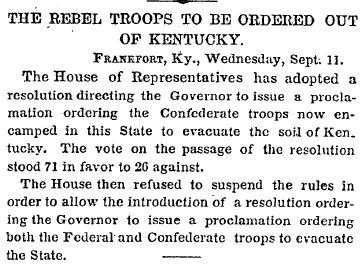

Kentucky, at this time, was tenuously holding to the position that it was a neutral entity, not engaged in the military struggle between the States. Although its governor, Beriah Magoffin, was pro-Confederate in sympathy, the State Government continued to function and a developing majority of its members was slowly swinging its support toward the Union. By the time Fremont issued his proclamation, Lincoln was actively encouraging the Union elements in the State, by shipping rifles into the state and supporting the set up of recruitment camps. By late August, the secessionist movement no longer seemed to have any prospect of success, and the State's politics were trending toward abandoning neutrality in favor of actively engaging in the war on the side of the Union.

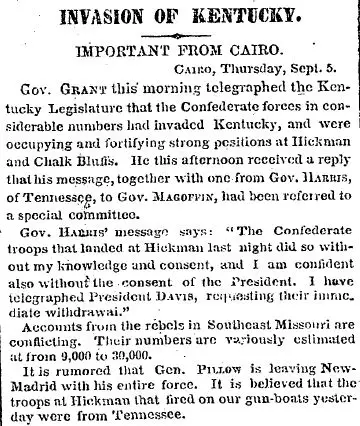

Fremont's proclamation caused the pro-Union movement to hesitate and this seriously threatened a reverse in Kentucky's course. Joshua Speed, a Kentuckian and one of Lincoln's oldest friends, wrote him to say at this time, "I have been so distressed since reading that foolish proclamation of Fremont that I have been unable to sleep or eat. To wage war in a slave state on such a principle as the proclamation expresses" is stupid; "you might as well attack the freedom of worship or the right of a parent to teach his child to read." Speed's letter was followed by a shower of telegrams reaching Lincoln's desk from various parts of the State, with the unanimous cry—"There is not a day to lose in disavowing emancipation or Kentucky is gone over the mill dam." Lincoln reacted to this, on September 4—the day the Confederates, under Gideon Pillow, occupied Columbus, Kentucky, in force—by asking Fremont to modify his proclamation, to conform its terms to those of the congressional act of confiscation. Lincoln wrote Fremont, on September 2, 1861, "I think there is great danger, in relation to the liberating of slaves of traitorous owners, that our southern Union friends will be alarmed and turn against us; perhaps ruin our rather fair prospect for Kentucky." (How Fremont's proclamation accentuated this "alarm" more so than did the Congressional confiscation law, Lincoln did not explain.)

Fremont, not quite as unreasonably as the historians tend to say, flatly refused. He was the military commander of the department, after all, and the department was seriously being disrupted by an extremely hostile population in the countryside, especially in the section of the State north of the Missouri River, that was tearing up the railroad tracks faster than they could be repaired, burning railroad bridges, and relentlessly murdering Lincoln's dear Union friends. Indeed, Fremont had been the first standard bearer of the Republican Party, had run on the platform of freedom for the slaves, (something Lincoln had not done.), and he was clearly in full agreement with the Radicals of the party who were then beginning to stand in the Senate and House of Representatives to make fiery speeches designed to force that very issue home to a conclusion.

Fremont politely replied to Lincoln, on September 8th, writing: "I did it, acting solely with my best judgment to serve the country and yourself. This is as much a movement in the war as a battle, and in going into these I shall have to act according to my judgment, as I did on this occasion. If you still decide I am wrong I have to ask that you openly direct me to make the correction. If I were to retract it would imply I myself thought it wrong, but I thought it was a measure right and necessary and I think so still." Lincoln accommodated him quickly.

By September, Fremont was spending hundreds of thousands of dollars turning St. Louis into a fortified city on the scale that Washington was, while the entire state continued to be embroiled in guerilla warfare; worse, the Union columns in the field were suffering reversals. Lyons had been killed at Springfield, his associate, Franz Sigel, thereafter had made a hasty retreat toward Rolla, and Price had moved north and captured a 2,400 man Union garrison at Lexington and was now dallying between the two points. At the same time, Confederate forces were appearing at New Madrid and Columbus, Kentucky, with elements trending northward toward the Iron Mountain Railroad connecting St. Louis to Ironton.

Fremont reacted to these events, by making some important decisions which would prove to have a dramatic effect on the progress of the war: he made a perhaps not so surprising change in district commanders; he supported a movement that resulted in the seizure of Paducah and Smithland at the mouths of the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers; he ordered a concentration of forces at Jefferson City, for a movement westward against Price and McCulloch; and he intensified efforts to suppress the civilian marauding that was going on in the counties north of the Missouri.

He was doing these things under circumstances in which the Lincoln Government had not yet fully supported him with money and supplies: his troops were operating at this time woefully short of shoes, clothing, food, ammunition, efficient rifles, wagons, horses, and artillery.(Of course, the Confederate commanders were in the same boat.) While his aggressive efforts were in progress, not only did Montgomery Blair, Postmaster General, and Montgomery Meigs, the Army's Quartermaster General, appear at St. Louis to "investigate" the situation; but also Simon Cameron, Secretary of War, and Lorenzo Thomas, Adjutant General of the Army, showed up. Cameron had in hand a letter authorizing Fremont's removal from command, which he showed Fremont but did not officially serve, because Fremont, then at Jefferson City, convinced him that he was entitled to a chance to prove himself in the field.

What objectively justified Lincoln's decision to discharge Fremont at this point is difficult to fathom, unless you are an academic historian repeating the myth of history. Fremont had arrested, released, and rearrested Frank Blair, Jr. for "insubordination" during this time. Blair and Fremont had been at loggerheads, because Fremont would not give Blair's cronies the contracts they coveted. Fremont was indeed prancing about, somewhat ostentatiously, with a crowd of over-dressed foreigners around him, and, no doubt, his cronies were making huge war profit from their relationship with him. But this was standard operating procedure for many politicians and military officers in position to take personal advantages. (As to the latter point Cameron, himself, was well known to be doing exactly the same thing.)

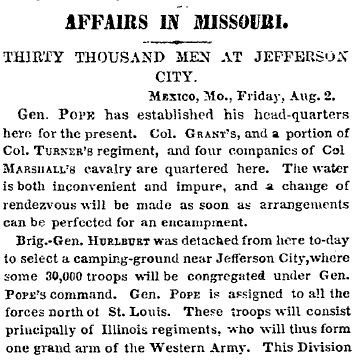

Perhaps, to escape the necessity of interviews, the embarrassing politics, or to rehabilitate his shrinking standing with Lincoln, Fremont left St. Louis and went to the front, personally leading an army of three newly organized divisions, under the command of Franz Sigel, John Pope, and David Hunter, out into the field to do battle with Price and McCulloch. Eventually, in late October, Fremont's army converged on Springfield which Price had abandoned a week before. By November 2, all of the divisions were in line of battle, Fremont apparently expecting to be attacked at any moment; then, suddenly, David Hunter appeared with Lincoln's order relieving Fremont of command in hand and delivered it.

Whether Fremont's dismissal was based on the actual record of his military performance as department commander, or was the consequence of his taking to himself all political power within the department or because of financial mismanagement remains a question unanswered persuasively by the historians. Clearly, Lincoln's organizing a formidable party to confront Fremont in St. Louis suggests Lincoln saw Fremont as a political power to be reckoned with. Lincoln's real concern with Fremont may well have been the fact that, by his political actions, Fremont was positioning himself to be the leader of the Radical faction of the Republican Party, and, therefore, becoming an obstacle to Lincoln's ability to control the party's war agenda, and therefore had to be removed.

Fremont's Bodyguard Charges Through Springfield

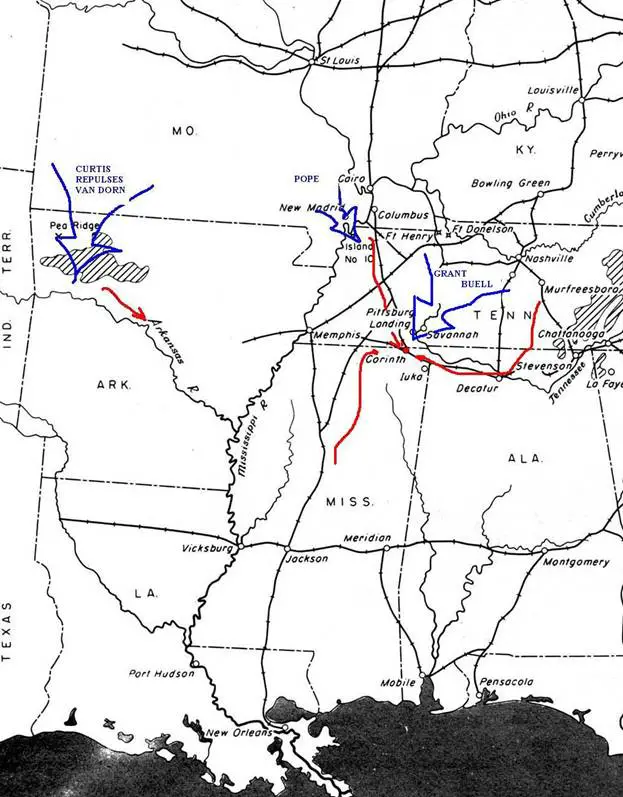

Seven days after dismissing Fremont, Lincoln named Major-General Henry W. Halleck commander of the Department of Missouri. Within three months of that date, Halleck's administration of the department, acknowledged by all to have been in chaos when he took it over—with most of its troops unpaid, many without clothing and arms, large numbers absent from duty, and the rebels holding sway almost everywhere—had resulted in Missouri and Kentucky being completely cleared of enemy troops, and his several army corps, under the field command of Curtis, Pope, Grant and Buell, were penetrating deep into Arkansas and Tennessee, gathering themselves by the end of March to move on the strategic point of Corinth, Mississippi—the crossroads of the Mobile & Ohio Railroad and the Memphis & Charleston Railroad. Then, Halleck thought, it would be "on to Memphis!"

Henry Halleck's record, during this period, is a string of military victories. Concentrating, first, on clearing Missouri, Halleck managed the operations of three armies, one operating in eastern Missouri with the objective of clearing the Mississippi down to the Arkansas border, another operating in the southwestern corner of the state, with the objective of pursuing the enemy into Arkansas, and the last operating up the Tennessee River. As the first two objectives were achieved, Halleck niftily shifted his resources from Missouri to Kentucky, ordering Grant, who had emerged from the pack of regimental officers as a brigadier-general in command at Cairo, Illinois, to capture Fort Henry and thereby threaten Sidney Johnston's rear at Bowling Green. This movement, in conjunction with Buell's crossing his army over the Barren River, caused Johnston, who could not stand a battle against Buell's superior force, to abandon Nashville and retreat into Alabama.

As a consequence of Halleck's success, Lincoln caused the Department of Missouri—renamed the "Department of the Mississippi"—to be extended to include the territory between the Tennessee River and the Barren River down to the Alabama and Mississippi borders which brought Buell's army under Halleck's command, and, suddenly, Ulysses Grant was a major-general of volunteers outranking everyone except Halleck, Pope, and Ethan Hitchcock, grandson of Revolutionary War hero Ethan Allan and a Lincoln military advisor.

Hitchcock was brevetted a brigadier-general for his conduct at the battle of Molino del Rey during the war with Mexico, became colonel of the 2nd U.S. Infantry Regiment, in 1851, commander of the Department of the Pacific, in 1864, and, when made a major-general, became a special advisor to Edwin Stanton, Secretary of War on February 17, 1862, a position that lasted until November 1862. As such, Hitchcock acted as President of the "War Board" which was composed of a group of staff officers who provided counsel and advise to Lincoln. Lincoln had plenty of "advisors."

Ethan Allan Hitchcock

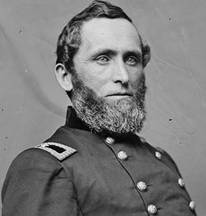

John Pope's Star Rises

|

On February 17, Halleck had ordered Grant to stop where he was, at Fort Donelson, and directed that all reinforcements previously ordered to move up the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers were to retrace their route and go to Pope's headquarters which was now in southeastern Missouri. On February 18th, Halleck ordered Pope to organize these troops into the "Army of Mississippi" and use them to capture New Madrid and Island No. Ten. Halleck's idea, here, much like Fremont's before him, was to get in the rear of the Confederate stronghold at Columbus, cut off its communications with the South and thereby clear the Mississippi River down to Memphis. Once Columbus was abandoned by the rebels, Halleck could use the Mobile & Ohio Railroad to support his armies' movement on Corinth, Mississippi. Grant, though, had a different idea which Halleck eventually came around to. But, first, the paramount objective was to clear the Mississippi River as far downstream from Cairo as possible and in this endeavor, Halleck first thought John Pope was the man. |

When

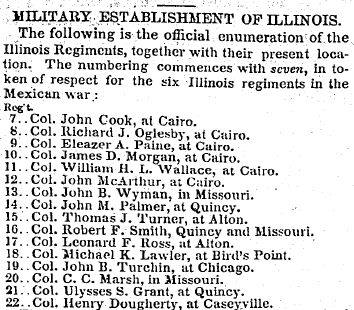

the war commenced, in April 1861, John Pope was a first lieutenant in the U.S.

Army; trained as a topographical engineer, he was then stationed at Cincinnati with the assignment of planning lighthouses for the Great Lakes. Previous to

this, he had spent seventeen years mapping and exploring trails across the Great Plains. A family friend of Lincoln, Pope had accompanied the president-elect on the

train ride that carried him to his inauguration at Washington, in March 1861.

Within a day of Sumter's fall, Pope wrote a telegram to Illinois Governor

Richard Yates, offering his services. Yates responded, with an offer to make

Pope the State's "mustering officer." Pope immediately accepted

Yates's offer and, after obtaining, through Lincoln's intervention, a leave of

absence from the Regular Army, he went directly to Springfield. Pope performed

the duties of State Mustering Officer for about a month; by May 5, he had

mustered into the Illinois State Militia six volunteer Militia regiments whose

members had volunteered to serve for ninety days.

When

the war commenced, in April 1861, John Pope was a first lieutenant in the U.S.

Army; trained as a topographical engineer, he was then stationed at Cincinnati with the assignment of planning lighthouses for the Great Lakes. Previous to

this, he had spent seventeen years mapping and exploring trails across the Great Plains. A family friend of Lincoln, Pope had accompanied the president-elect on the

train ride that carried him to his inauguration at Washington, in March 1861.

Within a day of Sumter's fall, Pope wrote a telegram to Illinois Governor

Richard Yates, offering his services. Yates responded, with an offer to make

Pope the State's "mustering officer." Pope immediately accepted

Yates's offer and, after obtaining, through Lincoln's intervention, a leave of

absence from the Regular Army, he went directly to Springfield. Pope performed

the duties of State Mustering Officer for about a month; by May 5, he had

mustered into the Illinois State Militia six volunteer Militia regiments whose

members had volunteered to serve for ninety days.

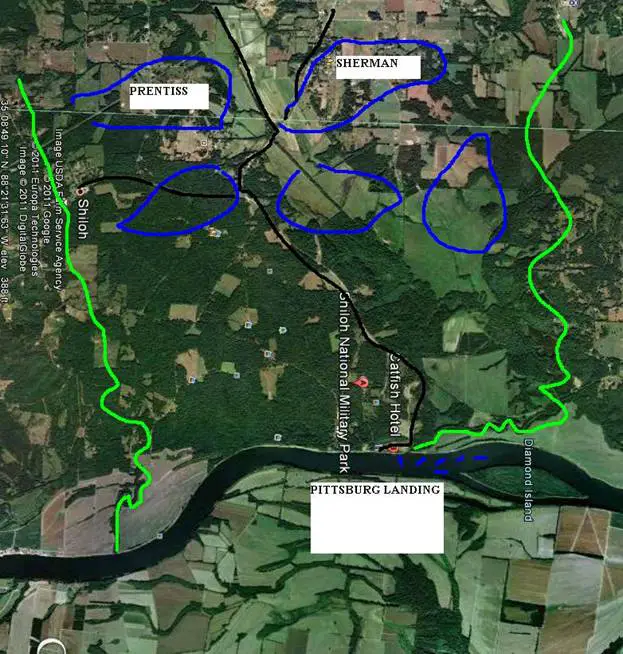

During this time, Pope tried to gain the position of Militia General for Illinois, but Governor Yates allowed the men in the ranks of the six regiments to vote for the man they wanted to fill this position and they chose Benjamin Prentiss. Prentiss, an active Republican, had led a company of Illinois volunteers in the war with Mexico, seeing action at a number of battles. After the war he remained active in the Illinois Militia, rising to the rank of colonel. Losing out to Prentiss, Pope then turned to his social and political connections—he had married into a wealthy Republican Ohio family and he was on first name terms with the key Republicans in both Ohio and Illinois—to press Lincoln for appointment as a brigadier-general in the Regular Army. Instead, Lincoln appointed him, along with another Illinoisan, Stephen Hurlbut, a brigadier-general of volunteers.

![]()

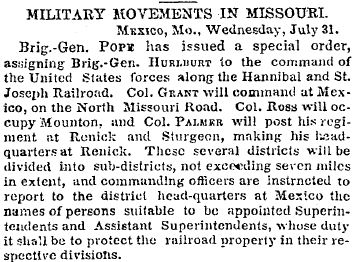

When Congress convened its special session on July 4th, Lincoln's nominations, including that of George McClellan, then Ohio Militia General, to major-general of the Regular Army, were confirmed by the Senate and McClellan ordered Pope to take command of six Illinois volunteer regiments stationed at Alton, Illinois. Soon after Pope arrived at Alton, Nathaniel Lyon, commanding the Missouri Volunteer forces, asked Governor Yates to provide Illinois troops to guard the Hannibal & St. Joseph Railroad. This railroad provided western Illinois with the means of communicating with Kansas and the West, and Governor Yates, wanting to keep it open to Illinois commerce, ordered Pope to move into Northern Missouri and cooperate with Lyons. (During the period of ninety day enlistments, specified by Lincoln in his first call for volunteers, the state governors commanded their state militias and assigned the general officer slots; this practice was cut out when the three year enlistments began replacing the ninety day enlistments.)

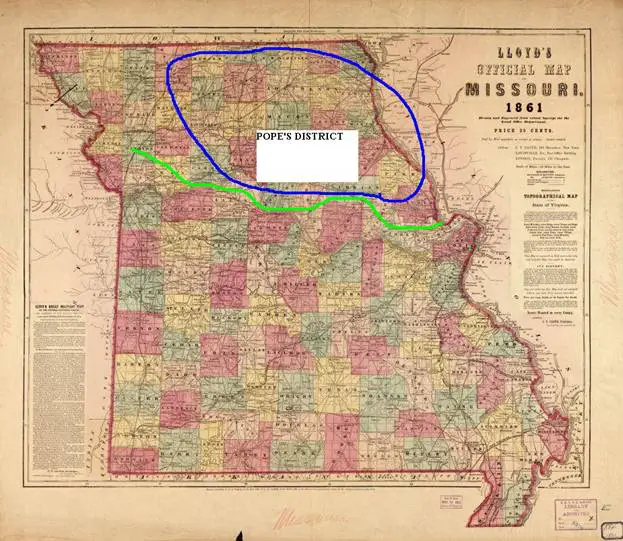

Two weeks later, John Fremont took command of the western department and placed Pope in command of the District of North Missouri, with instructions to suppress marauding and cover the railroads. Pope was energetic in executing Fremont's instructions: spreading his regiments through the district, posting forces at the county seats of each county, he forced the citizens in each county to form "safety committees" the function of which was to preserve order. Pope was the first in this regard to impose military force on a civilian population in the Civil War.

Notice to the People of Marion County

HEADQUARTERS DISTRICT OF NORTH MISSOURI

St. Charles, July 21, 1861

I desire the people of this section of the State to understand distinctly that their safety and the security of their property will depend upon themselves, and are directly and inseparably connected with the security of the lines of public communication.

It is very certain that the people living along the line of the North Missouri Railroad can very easily protect it from destruction, and it is my purpose to give them very strong inducements to do so. I therefore notify the inhabitants of the towns, villages, and stations along the line of this road that they will be held accountable for the destruction of any bridges, culverts, or portions of the railroad track within five miles on each side of them. If any outrages of this kind are committed within the distance specified, without conclusive proof of active resistance on the part of the population, and without immediate information to the nearest commanding officer, giving names and details, the settlement will be held responsible, and a levy of money or property sufficient to cover the whole damage done will be at once made and collected. If people who claim to be good citizens choose to indulge their neighbors in committing these wanton acts, and to shield them from punishment, they will hereafter be compelled to pay for it.

To carry out the intentions set forth above, divisions of the road will be made from these headquarters, and superintendents appointed by name, without regard to political opinions, who will be held responsible for the safety of the railroad track within their specified limits. They will have authority to call on all persons living within these limits to appear in such numbers and at such times and places as they deem necessary to secure the object in view.

JOHN POPE

Brigadier-General, U.S. Army, Commanding North Missouri

With this "notice" Brigadier-General Pope, of the U.S. Army Volunteers, joined a long list of soldiers who have ignored the laws of war, punishing the civilian population of a militarily occupied territory with the summary use of military force, as the Germans did to the French in World War II, the American army did to village people in Viet Nam, and, it is hard to ignore, also in Iraq and Afghanistan. As Pope explained, when called to account for this conduct, it is the way of the military in the circumstance—they call it today, "counterinsurgency measures." Responding to inquiries from important Missourians, Pope wrote this:

"When I arrived in North Missouri to assume command I found the whole country in commotion, bridges and railroad tracks destroyed, and the entire population in a state of excitement. My first object was to restore quiet and secure the property from marauders.

As soon as these marauders found that troops were approaching, which they easily did, from the very persons who ask for protection, they dispersed to their homes, sure that their neighbors would shield them from exposure.

Two courses were open to me to stop this: the first was to use small bodies of troops to hunt down the parties in arms. This course would have led to frequent and bloody encounters, to searching of homes, and arrests in many cases of innocent persons, and would only have resulted in spreading the apprehension of distress over districts hitherto quiet. To spare the effusion of blood, destruction of life or property, and harassing and ofttimes undiscriminating outrage upon the people, I have determined to present the people, some common inducement to preserve the peace in their own midst. The common bond is their private property, always in my power, though the owner might be beyond my reach. I have not the slightest inclination to play the tyrant to any man on earth. If the people keep the peace they will neither see me nor my command."

The complaints Pope had received from influential Missourians eventually reached John Fremont's desk and he called Pope to St. Louis, in late August, for consultation about them. Upon leaving the conference, Pope wrote Fremont this epistle:

"This system of holding property of counties responsible for breaches of the peace enlists the active agency of the secessionists in keeping down riots and disturbances. When so large a portion of the population sympathizes with the authors of the atrocious acts of guerilla warfare, it is impossible to apprehend the perpetrators of such outrages. Since the population has been notified that their property would be made to pay the expense of suppressing such disturbances, thousand of persons have taken part in preventing them. Marion County, from which came the protests against this policy, has been the worst county in the State. Whenever it is discovered that the policy will not be executed, I firmly believe that every county will be in a state of tumult, and will require for the restoration of peace five times the force now needed.. Therefore I recommend you make no favorable reply to those complaining of this policy. True, there is a risk of alienating a few men hitherto half-way for the Union; but there is great risk, if it is not enforced, of having every county in arms against the peace."

The Counties of Missouri

Marion County, in 1862, was the site of a massacre

caused by Union troops.

It appears from the record that the Missourians' complaints to Fremont passed without a change of military policy, as Afghanistan President Karzi's complaints of constant home invasions in the night have gone ignored today: so much for Bush's guru general, now Obama's CIA Director, Petreaus's "original" book on "counterinsurgency" tactics.

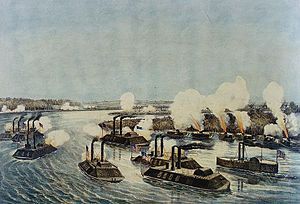

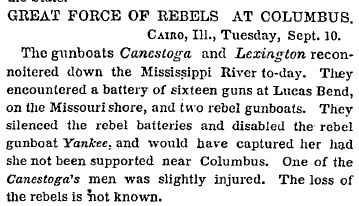

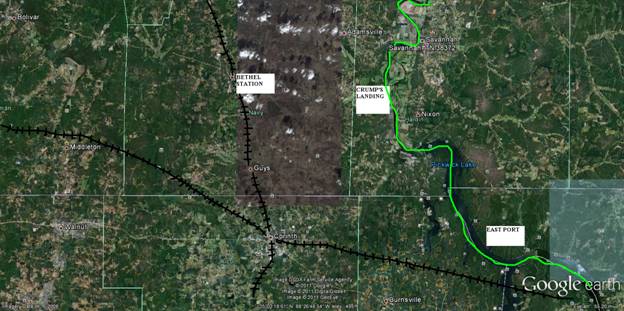

Then, with Fremont removed and Halleck in his place, Pope found himself, on March 3 1862, with an army of 10,000 in front of New Madrid; and the next day he ordered an attack. The attack failed when Confederate gunboats, unopposed by Union gunboats, which at the moment were unable to get past shore batteries on the northern reaches of the river, covered the Confederate infantry with the fire of their guns.

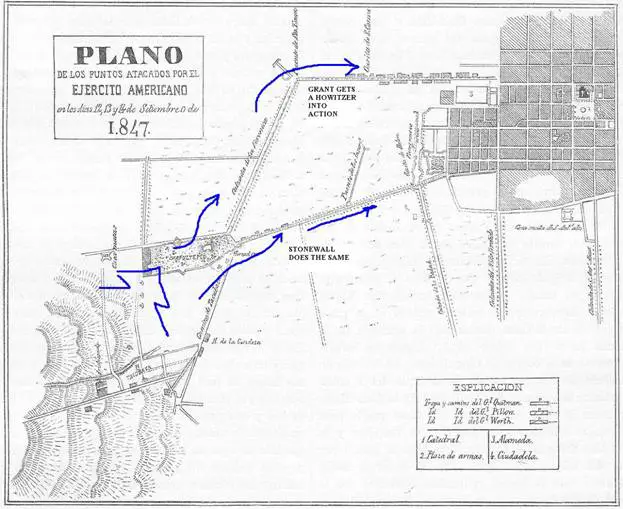

Pope brought down from Cairo more artillery and, by March 12th, he was pounding the Confederate position at New Madrid and suppressing the fire from the Confederate gunboats. This induced the Confederate commander to abandon New Madrid the night of March 14th, taking his men by ferry across the river and into the peninsula formed by the bend you see in the image.

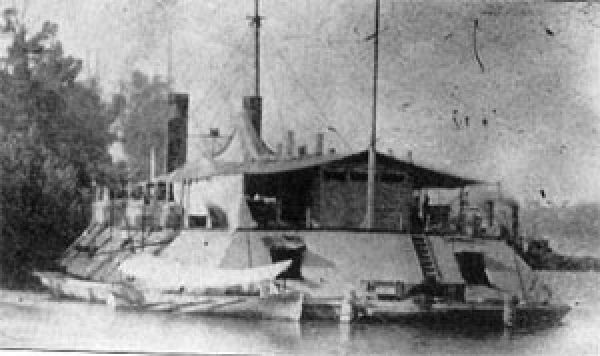

At

this point, Halleck sent Foote's flotilla of gunboats, which after Donelson, had

refitted at Cairo, down the Mississippi to support Pope's effort. The gunboats

arrived on March 16th and tied to the shore at a point just north of Island No.

Ten. On March 17th, Foote's gunboats and mortar boats barraged the Confederate fortifications

but accomplished nothing. The Confederates had forty-nine guns in operation and

the artillery exchange resulted in serious damage to several of Foote's boats.

Afraid his boats would float downstream into rebel hands if they became

disabled, Foote backed off.

At

this point, Halleck sent Foote's flotilla of gunboats, which after Donelson, had

refitted at Cairo, down the Mississippi to support Pope's effort. The gunboats

arrived on March 16th and tied to the shore at a point just north of Island No.

Ten. On March 17th, Foote's gunboats and mortar boats barraged the Confederate fortifications

but accomplished nothing. The Confederates had forty-nine guns in operation and

the artillery exchange resulted in serious damage to several of Foote's boats.

Afraid his boats would float downstream into rebel hands if they became

disabled, Foote backed off.

Now came the first canal-digging venture of the war. In order to capture the rebel position, Pope had to get his infantry across the river and into the mouth of the peninsula. To do this, he decided to dig a canal through the swampland that bordered the river on the west bank and in that way get transport boats to New Madrid which he could then use to move his army from the west to the east bank and attack the rebel fortifications from the rear. Three weeks were spend in this endeavor: Eight hundred black laborers, by removing snags and dead trees from the mud bottom, threaded a shallow channel through the swamp over a 15 mile course. Presumably they were paid.

Then, on March 30, with this work completed, Flag Officer Foote found a volunteer, Captain Walke, of the Carondelet, willing to attempt to run past the rebel batteries; the idea being to get some gunnery support to Pope as he attempted to cross his troops over the river in the transports. The stage was now set for Pope to emerge as a principal player in the opening of the Mississippi River down to Memphis and win from Lincoln the coveted commission as a Regular Army brigadier.

Carondelet

Grant's Star Almost Crashes

The record seems to show that Ulysses Grant was, in fact, a strange, sullen sort of man. Raised in rural southern Ohio, he spent his youth working for years against his will in his father's tannery, scraping blood and bits of bone and muscle off the bloody hides of dead animals. As a young boy he was worked hard; when not scraping cowhides, he was working on the family farm, doing "all the work done with horses" the experience making him a master horseman. His father, Jesse, was successful at the tannery business and had money in the bank which he used eventually to bankroll a leather goods business, to be run by Ulysses's two younger brothers, Simpson and Orvil, in Galena, Illinois. For whatever reason, however, instead of grooming Ulysses to work in business with his other sons, Jesse pushed him into West Point. The father must have seen something in the son that he thought was special; watching how his son got hard things done, it might well have been the trait of initiative he saw and it made him think of West Point. Or, perhaps, it was just that he realized Ulysses was smart and a college education could be gained for him that cost his father nothing.

Initiative: 1. the action of taking the first step; responsibility for beginning; 2. ability to think and act without being urged.

Grant entered West Point in 1839 at the age of seventeen. His classmates included George McClellan, William Sherman, James Longstreet and Stonewall Jackson. Upon graduation, in 1843, as a second lieutenant of infantry, Grant, with his West Point roommate, Charles Dent, was stationed at Jefferson Barracks, St. Louis, and there he met and married Julia Dent, Charles's sister. Two years later he was at the Rio Grande River, with Zachary Taylor's small army, and, engaging as an infantry company commander in the actions at Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma, he witnessed at close hand men being maimed and killed around him as he charged the Mexican cannon with the rest of Taylor's little army. At this early moment, it seems Grant learned something about the horror of war; writing Julia, he said: "The woods was strewn with the dead. Wagons, how many I cannot guess, drew the bodies to burial." As to the stress of battle felt to himself, he wrote her: "There is no great sport in having bullets flying about one in every direction, but I find they have less horror when you are among them."

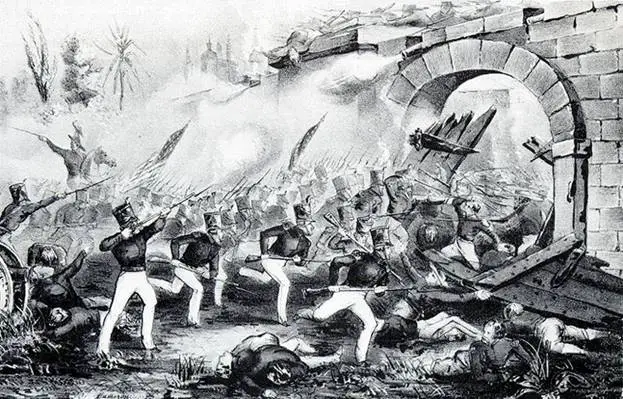

After these actions, Taylor invaded Mexico, marching his column of 3,000 men to Monterrey; there, Grant rode a horse, until it was shot from under him, in the charges on the city's fort as about a third of the men involved fell killed or wounded. Once past the fort, Grant ran with the infantry attack force through the town, darting from house to house, down one street, then another, until, just as Worth's army was arriving from the opposite direction, the recall was sounded and the battle died out, allowing the Mexican troops to leave the place with their arms intact. Then, in 1847, Grant, now a quartermaster, was sent, with his regiment, to join General Scott who had arrived at Vera Cruz with 10,000 men. As a consequence, Grant saw action at the Pass of Cerro Gordo, on the climb out from the sea; at Puebla, where Scott built up a depot of supply, and then at the approaches to Mexico City—Molino del Rey and Chapultepec—and finally at the city itself, he led a squad of men, dragging a howitzer into a church belfry and dispersed the Mexicans defending the city's San Cosme Gate.

The Assault on the City of Mexico, September 1847

The Volunteers' Break Through at the San Cosme Gate

Four years later, married now to Julia Dent, Grant and his 4th Infantry company, arrived at Fort Columbus, Oregon, alone. His wife was pregnant with their first child and could not come; and after delivering the child she did not come. After a leave of absence that got his wife pregnant a second time, he was transferred to Fort Humbolt, at Eureka, California. There, isolated and alone in a place almost constantly shrouded in the cold gloom of the North Coast, without the companionship of a wife and never having seen his children, it is said, with some authority, that Grant began to drink.

Fort Humboldt

As the spring of 1854 was beginning, with no sunshine, Grant received notice of promotion to captain and, after accepting, at once resigned his commission. In the last letter he wrote Julia from Humboldt, his words seem to make plain that his unhappiness may have been occasioned in large measure by his wife's voluntary absence. "Dear Wife," he wrote her on May 2, 1854, "I have not received a letter from you and as I will be away from here in a few days do not expect to. You might write directing it to New York City." Five months later, he was reunited with her at her family's home at St. Louis and within a week she was pregnant with their third child.

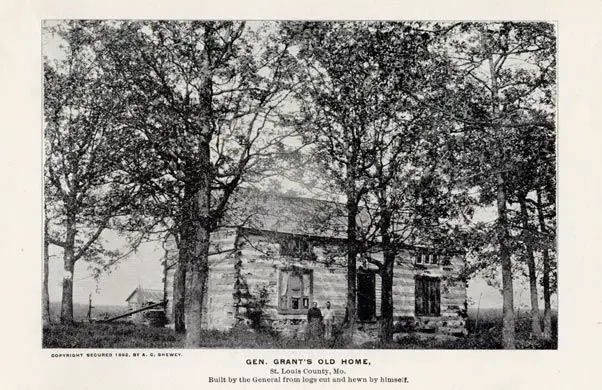

The Dent Family Home

Julia's father, a slaveholder and large scale farmer, gave Grant some acreage to begin a farm. Grant cleared the land of trees, using the lumber to build a two-story house.

Julia was not happy: "Is this my destiny?" she wrote years later about the experience. Julia, in her father's "nice frame house," had had financial advantages and enjoyed material advantages that life on the "farm" apparently denied her. There, it became evident there was little money available for anything other than the necessities of life and this bothered her. Farmers were generally suffering at this time and Grant shared in it; for two years, the income from his crops and cordwood sales, the historians say, barely covered household expenses and the cost of hiring slave labor. (Yet, Julia owned four slaves, one of which, a maid, she took with her, during the war, when she visited her husband in camp. In 1859, Grant manumitted the one slave that he owned.) Whether, by the spring of 1860 Grant was as poor as the historians say, he joined the family leather business in Galena, Illinois, and put his wife and children in a rented frame house (A more objective reason for doing this is that his brother Simpson was terminally ill and was no longer available to help in the family's Galena business.)

The Grant Family's Home in Galena, Illinois

|

One year later, Grant accompanied a company of Galena volunteers to the Illinois State Capitol at Springfield and, within a few days, found himself appointed by Governor Yates to the position of the State's Mustering Officer. As the historians tell it, Grant arrived at Springfield, a confirmed failure in life, a man of no reputation and no promise, seedy in appearance, with a near hobo-like demeanor. Nothing could be farther from the objective truth.

Grant and the Galena volunteers arrived at Springfield on April 25, 1861, and he went with them to Camp Yates, the State's mustering grounds. Here he came in contact with John Pope, who then held the position of State Mustering Officer. The two men had been classmates at West Point—Pope being a year ahead of Grant—and they both had been with Zachary Taylor's army as it came upon Monterrey and had run together under fire through the city streets. Pope, as a topographical engineer, was with Captain Joseph Mansfield, at one point crouched against a wall as canister fire from the Mexican artillery raked the streets; and Grant, not far away, had a horse shot from under him as he tried to bring ammunition to his comrades while Taylor's wing of the attack was giving way. At the end of the day, as the fire was dying away, and a sort of truce prevailed, they had both walked among the dead bodies of the soldiers lying in the streets, looking this way and that, for wounded; both drenched in dripping sweat by the experience of war.

|

Meeting at Springfield, the two men could not help but clap each other on the back as brothers-in-arms, and Pope took Grant to Governor Yates and recommended Grant as his replacement. Benjamin Prentiss, the Militia general, had been given command of Illinois forces, at Cairo, protecting the southeastern sector of the state, and Pope, soon to be a brigadier-general of volunteers, was to protect the northwestern sector by taking control of the railroads in North Missouri. Happy to have another West Point graduate at his call, Governor Yates quickly offered the job of Mustering Officer to Grant and Grant accepted. Six weeks later, on July 17, 1861, with all the State's allocated regiments now mustered in and split between Pope and Prentiss, Yates appointed Grant, colonel of the Twenty-First Illinois Volunteer Regiment, and assigned him to Pope's command.

![]()

![]()

In the month that followed, Grant's regiment marched to Quincy, coming under the command for a time of Brigadier-General Hurlbut, and, then, receiving orders from Pope, who had been placed by Fremont in command of North Missouri, he marched his regiment into Missouri, taking post at Palmyra, on the line of the Hannibal & St. Joseph Railroad. By July 19th, Grant was under orders to take his regiment on a steamer to St. Louis, for transit down the Iron Mountain Railroad to Ironton, but the steamer failed to arrive and the order was countermanded by McClellan. In the absence of Fremont, who was enroute to St. Louis from New York, and Nathaniel Lyon who was about to join battle with Price at Wilson's Creek, Lyon's adjutant, in command at St. Louis, had asked Pope for troops to cover Ironton in the face of Confederate forces appearing in force on the west bank of the Mississippi.

Grant's Countermanded Orders Would have Placed Him At Ironton

On July 25, Fremont reached St. Louis, and taking command of the department, issued movement orders, to counter the Confederate threat that had materialized in the southeast sector of the State when Polk and Pillow, with 10,000 men, appeared at New Madrid. (By this time, both Pope and Hurlburt were brigadier-generals of volunteers; Prentiss, a militia brigadier at this time, was about to become, along with Grant, a brigadier general of volunteers—all four of these men were Illinoisans.) Once, again, John Pope stepped up as Grant's sponsor, introducing Grant to Fremont when they met in St. Louis as "an old Army officer of intelligence and discretion, thoroughly a gentleman and a prudent man who is eminently needed now." (So much for the historians' narrative of Grant's woebegone status among his acquaintances.)

The first thing Fremont appears to have done upon his arrival in St. Louis was to take a steamer down the Mississippi and inspect the situation of Prentiss's command at Cairo. Prentiss was struggling at this time with the transition going on, reorganizing the men in the ninety day volunteer regiments, whose enlistments were expiring, into three year regiments. On July 30, Fremont wired Lincoln: "Within a circle of 50 miles around Prentiss there are about 12,000 rebel troops, and 5,000 Tennesseans, under Hardee, are advancing on Ironton." On August 1, he reached Cairo with eight transports, bringing reinforcements. Fremont remained at Cairo for five days, in the course of which he had plenty of time to evaluate Prentiss as a soldier. Returning to St. Louis, on August 6, Fremont sent orders to Pope to detach the 14th, 15th, and 21st Illinois Regiments from railroad guard duty in North Missouri, and send them to St. Louis.

As the regiments were marching, word came to Missouri that the Senate had approved Lincoln's appointment of both Prentiss and Grant as brigadier-generals of volunteers with date of rank retroactive to May 17. Clearly, Lincoln's appointment was caused by recommendations made by Illinois politicians, Governor Yates, Senator Trumbull, and Congressman Elihu Washburne, whose congressional district included Galena.

Fremont, though neither a graduate of West Point nor a veteran who had seen action in Mexico—he had been in California at the time, orchestrating the brief-lived Bear Flag Republic—no doubt had enough sense to respect not only Pope's opinion of Grant but also Grant's heavy record of battlefield experience gained in the Mexican War, because, on August 8, he chose Grant to command at the emerging hot spot of Ironton.

![]()

![]()

![]()

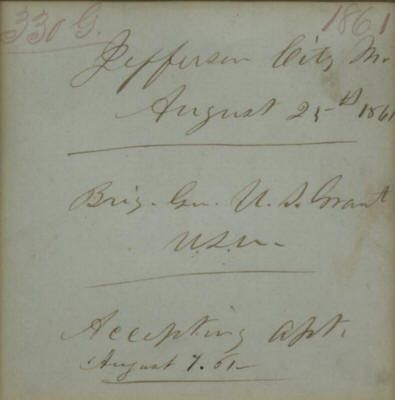

Grant's Formal Acceptance of Commission as

Brigadier-General was on August 25; before that date

Benjamin Prentiss had a legitimate case he was senior.

Note: Congress passed its first act, approving Lincoln's appointments, on July 18; it passed a second act, expanding the number of appointments authorized, on July 27, and a third act dealing with increasing major-generals and brigadier-generals in the Regular Army at about the same time.

On August 8, Fremont, at St. Louis, gave Grant new orders:

August 8, 1861—Morning

Brigadier-General Grant

Charged with the Command of the Ironton Force:

"A special train will be sent to take your regiment to Jefferson Barracks this morning. You will proceed with it (using the Iron Mountain Railroad) to Pilot Knob, and take command of the regiments stationed there under Colonels Brown, Hecker, and Bland. You will find an officer of engineers engaged in laying out entrenchments which you will push forward with all possible dispatch. It is intended to strengthen the frontier as to make it defensible against any force likely to be brought against it, and to this end additional men and stores will be immediately sent forward. You are to guard your front and be prepared for the contingency of a sudden movement with the force under your command. A locomotive has been placed at Ironton."

Here is the great turning point in which Grant emerges from the vast pack of regimental officers, coming suddenly into the command of the crucial strategic spot in the western theater which will send his star soaring. Before receiving these orders, Grant had arrived in St. Louis, on August 5, send down by Pope to influence Fremont to let Pope's counterinsurgency policy stick. (Grant, in his memoirs, does not mention his appearance in St. Louis or his meeting with Fremont, nor does he give John Pope the credit he obviously deserves for boosting him into position to gain the key slot in Fremont's department.)

Fremont Makes A Quick Double-Switch

On August 9, from Ironton, Grant makes his first report as brigadier-general: "I am led to believe," he writes Fremont, "there is no force within thirty miles of us that entertain the least idea of attacking this position. But many of the officers, here, seem to have so little command over their men, and military duty seems to be done so loosely, that I fear our resistance would be in inverse ratio of the number of troops to resist with. In two more days, however, I expect to have a very different state of affairs and to improve it continuously." (Initiative)

On August 10, Grant writes—"No information has been received to lead to the supposition that this place is in danger of attack. Hardee today is at Greenville, with 2,000 men and 6 field pieces. Another 1,000 are thrown forward to Brunot. I suggest that two regiments at St. Louis be sent here for drill and discipline." (This is a subordinate after his commander's heart.)

The Situation in the Southeast District

On August 12, Fremont writes: "Send one column to Frederickstown and one to Centreville, taking possession of both places to guard your flanks. Send a column to Greenville and keep the fortifications going."

At this point, Lyon is killed at Wilson's Creek. The War Department reacts to this by sending telegrams to the western governors calling for troops and artillery to be sent to Missouri. Orders go out from Fremont to send troops to Rolla on which Lyon's army, now under Franz Sigel, is falling back; and Pope's forces are moving toward Jefferson City—Fremont's fear being that Hardee, in combination with Price and McCullough, will move west to threaten the central part of the State.

On August 14, Fremont reports to Lincoln that Grant has been attacked at Ironton, the Iron Mountain Railroad seized at Big River Bridge, between Ironton and St. Louis, and he issues his proclamation announcing marital law. Since no such attack had occurred, it seems that Fremont was manufacturing a basis for taking over the State's functioning government. It is way past time that the historians stop playing games, with cause and effect.)

On August 15, Fremont receives this telegram from Lincoln: "Been answering your messages since day before yesterday. Do you receive the answers? The War Department has notified all the governors you designated to forward all available force, and so telegraphed you. Have you received these messages? Answer Immediately. A. Lincoln" (Clearly something for historians to juxtapose between Fremont's proclamation and the proof of the necessity of it.)

This, in Fremont's mind, must have been the great moment of crisis. The rebels are in the ascendant it seems: Lyon killed, Sigel retreating, Hardee and Price advancing. Cairo threatened. He reacts with a flurry of orders, to Pope, to Sigel, and, surprisingly, to Prentiss—for reasons not objectively clear from the record.

Note: Aroused by events to reinforce Grant's position at Ironton, does Fremont think that the rules of rank make Prentiss's claim to rank superior to Grant's? Or does he think Grant has in some way failed to execute the existing orders? It seems clear, by reference to subsequent events, that Fremont must have, for a moment, misunderstood the rules of rank. (Or the rules of rank were ambiguous: In the Mexican war, it seems to have been decided that Regular army rank outranked volunteer (militia) rank, which makes sense.)

On August 8, a civilian railroad manager, who have traveled with Grant to Ironton, wrote Fremont this: "I arrived here with General Grant and troops at 3:00 p.m. today, find all quiet. Gen. Grant I am pleased with. He will do to lead.

Saint Louis, August 15, 1861

Brig-Gen. B. M. Prentiss:

Sir: Four regiments of your command have been ordered to leave Cairo by steamboats and disembark at Cape Girardeau, where they will await orders. You are directed to repair tomorrow morning by railroad to that place, and with these troops, taking the cars of the Iron Mountain Railroad, proceed to Ironton. You will assume command of the whole force stationed at that place, and will at first secure communications from St. Louis to Ironton. After the accomplishment of this you will proceed to Frederickstown and to Centreville, take possession of those places, and secure those positions by a force sufficiently strong. You will then open communication with Cape Girardeau. You will also make reconnaissances in the direction of Greenville."

J.C. Fremont, Major-General Commanding.

Grant had sent Fremont a telegram on August 15th: "I note the arrival of two regiments of infantry. I have ordered the 21st Illinois forward on the Greenville road, and the 24th Illinois upon the Frederickstown road, with instructions to form a junction at Brunot. I expect to follow tomorrow." And he was actively carrying out these movements when Prentiss arrived on August 17th, with Fremont's order in hand.

As Grant tells it in his memoirs, though Fremont's order did not relieve him from duty at Ironton, he refused to serve under Prentiss: "I knew," Grant writes, "that by law I was his senior, and at that time even the President did not have the authority to assign a junior to command a senior of the same grade. I therefore started for St. Louis the same day." (Initiative) (Grant treated Prentiss shabbily when the tables were turned.)

At St. Louis, he had contact with Fremont's staff and found himself under orders to proceed to Jefferson City and take command at that post. On August 10, Fremont had received a telegram from Pope, requesting that Grant be ordered to report to him to relieve Gen. Hurlbut in the command "in North and Northeast Missouri." The request made, because Pope wanted Grant to "supervise the disaffected counties north of the Hannibal & St. Joseph Railroad." Grant arrived at Jefferson City on August 21 and remained there eight days. (This is a perfectly reasonable explanation for why Prentiss was now in command at Ironton. Fremont replaced Grant with him, because Pope wanted Grant back! The historians have got to get their act together: Grant, far from being an outcast, was perceived by both Pope and Fremont as a dynamite asset..)

On August 25, Fremont sent orders to Prentiss, now commanding in Grant's place at Ironton: "4,000 rebels are fortifying Benton, Mo. 1,500 more at Commerce. To disperse these forces a combined attack by your troops and those at Cape Girardeau has been determined upon. You are ordered to move forthwith to Dallas, then you will attack the rebels at Jackson, then, with Smith, you will march upon the enemy at Benton."

Two days later, Fremont makes an abrupt about turn: On August 27, he ordered Grant to leave Jefferson City and come to St. Louis. The next day, on August 28, he ordered Grant to proceed to Cape Girardeau and assume command of the forces at that place with the view to making a "combined attack with the troops at Ironton. Prentiss has therefore been directed to proceed toward Cape Girardeau. The force, now in command at Cape Girardeau, has been instructed to move toward Prentiss and unite with him at or near Jackson. You upon assuming command at Cape Girardeau will act accordingly." Then Fremont wrote a telegram to Prentiss explaining what was happening. (Back in the saddle again!)

To Benjamin Prentiss, Fremont wrote:

St. Louis, August 28, 1861

Brig. Gen. B.M. Prentiss:

Sir: Brigadier-General Grant has been directed to proceed to Cape Girardeau, assume command of the forces there, and cooperate with the troops moving from Ironton. When you were ordered to go to Ironton and take the place of Gen. Grant, it was under the impression that his appointment was of a later date than your own. By the official list published it appears, however, that he is your senior in rank. He will, therefore, upon effecting a junction with your troops, take command of the whole expedition."

J.C. Fremont, Major-General Commanding

Thus, topsy-turvy like, Grant regained command of the Southeast District of Missouri, including the garrison at Cairo, and held in his hands, suddenly, the grand opportunity to be in position, to drive the Union war effort deep into Tennessee and into Alabama. And Grant wasted no time taking advantage of it.

Four days later, on September 2, Prentiss, having reached Cape Girardeau, refused to execute Grant's orders.

HEADQUARTERS U.S. FORCES

Cairo, Ill., September 2, 1861

Major-General Fremont, commanding Western Department:

I left Cape Girardeau at 10 o'clock this morning. General Prentiss raised the question of rank, and finally refused to obey my orders. Last night he tendered his resignation and today he reported himself in arrest. I will forward by tomorrow's mail the charges.

U.S. GRANT, Brigadier-General

Nothing came of Grant's charges; upon Prentiss reaching Fremont's headquarters, he was sent to Pope's district where he assumed Grant's old place, guarding the Hannibal & St. Joseph Railroad from marauders and occupying the county seats. Benjamin Prentiss was suddenly in the outlands, but he would come under Grant's command, again, and he would save Grant's star from crashing. (It is obvious that, having sent Grant to Pope, Fremont wanted him back at the hot spot of Ironton.)

Grant Seizes Paducah

When he assigned Grant to command the District of Southeast Missouri, Fremont was thinking of the volatile situation in Kentucky, anticipating the necessity of seizing Columbus, Kentucky, and thereby extending the scope of his department to include western Kentucky and Tennessee. On September 3, Fremont directed Grant to occupy Belmont, a hamlet on the west bank of the Mississippi River, opposite Columbus, Kentucky, about 15 miles below the confluence of the Mississippi and Ohio rivers. Columbus was the rail head for the Mobile & Ohio Railroad.

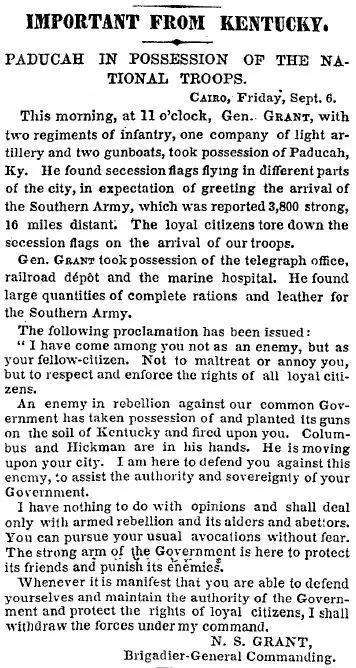

On September 4, from Cairo, Grant wired Fremont that his ability to keep a force at Belmont had been compromised by Prentiss's refusal to accept his orders, and he had to withdraw his position at Jackson, Missouri. Grant told Fremont that it was "advisable to withdraw the troops from Belmont until the command assumes shape for concert of action." Grant sent a second message that day to Fremont, advising that he believed the Confederate forces on the Missouri side of the river were retiring to New Madrid and that he thought it a good idea to take possession of Columbus as soon as the next day. Then, abruptly, Grant—learning that Confederate forces had occupied Columbus in force—wired a telegram to the Speaker of the Kentucky Legislature, at Frankfort informing him of that fact. (Initiative: Grant had no military authority to do this thing!) The next day, September 5, Grant received a message from Fremont which authorized him to take Paducah, if he felt strong enough. (Later Fremont reprimanded him for communicating with the Kentucky Government.)

Whether or not Grant was already in motion before Fremont's message reached him, the record is not clear. What is clear is that, late in the day, Grant went by steamer up the Ohio River and landed infantry at Paducah and occupied the place. Upon learning this, Fremont immediately assigned Brigadier-General Charles F. Smith, who had recently arrived from the East, to command the garrison at Paducah, reporting directly to Fremont, and he wrote Lincoln, asking that his department be extended to include the Tennessee River.

HEADQUARTERS WESTERN DEPARTMENT

September 8, 1861

THE PRESIDENT

My Dear Sir: As the rebel troops driven out from Missouri had invaded Kentucky in considerable force, and by occupying Union City, Hickman, and Columbus were preparing to seize Paducah and attack Cairo, I judged it impossible to defer any longer a forward movement. For this purpose I have drawn from the Missouri side a force which I have placed at Fort Holt (a fort Grant was constructing on the south bank of the Ohio) and Paducah, of which places we have taken possession.

I have reinforced, yesterday, Paducah with two regiments and as soon as General Smith, who commands there, is reinforced sufficiently, he will occupy Smithland, controlling in this way the mouths of both the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers. At the same time (a force should move on Bowling Green from Louisville) and meanwhile General Grant would take possession of New Madrid and the shore of the Mississippi opposite Columbus. A combined attack then will be made upon Columbus, and, if successful, we will move in concert, by railroad, to Nashville, Tenn, occupying the state capital. Then we would move on Memphis. (But Columbus was impregnable, it had to be flanked.)

By extending my command to Indiana, Tennessee, and Kentucky you would enable me to accomplish much.

Very truly yours, JOHN C. FREMONT

Two months later, after Fremont pushed forward a large force to Springfield, inducing the Confederate generals, Price and McCulloch, to fall back toward the Arkansas line, and Grant was keeping steady at Cairo and Paducah, Lincoln, determining to let Fremont go, for a number of reasons, the most pressing apparently being Fremont's gathering of political power, reached out to Henry Halleck.

McClellan communicated the assignment to Halleck on November 9, writing that he should concentrate the "mass of the troops in the department on or near the Mississippi, prepared for such ulterior operations as the public interests may demand." At this time Fremont had the troops organized as follows:

North Missouri (under Pope) 5,400

At Jefferson City 9,600

At Rolla 4,700

At Lexington 2,400

Total 22,100

At Cairo (under Grant) 15,500

At Paducah (under Smith) 7,000

Total 22,500

Soon after Halleck assumed command of the department, the concept of a campaign designed to drive the Confederates out of Kentucky began to develop in the War Department. Don Carlos Buell, assigned to command the Department of the Ohio, was the first to formally submit in writing the idea that a force be moved down the Louisville & Memphis Railroad to Bowling Green in conjunction with two flotillas of gunboats steaming up the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers, so as to threaten Confederate forces at Bowling Green and cut off communications between that place and Columbus.

The execution of this plan was delayed for three months by several circumstances: first, its execution had to wait until sufficient ironclad gunboats had been delivered to Cairo for use on the rivers; second, Lincoln and McClellan pushed Buell for a number of months to divert his effort on reaching Bowling Green in favor of pushing a column from Louisville to Knoxville, a distance of 250 miles, the column to move without benefit of either railroad or river; third, before Halleck could sufficiently reinforce the expedition on the rivers, ensuring success in accomplishing its objective, he had to clear Missouri of Confederate forces.

Halleck Wants To Dump Grant

Henry Halleck was a 4th year classman at West Point the year Grant entered as a plebe. He was also an instructor of chemistry, French, and engineering, and in that capacity had come into contact with Grant as a student, though Grant claimed later not to remember this.

Charles

F. Smith, the brigadier-general commanding the forces at Paducah and Smithland,

independent of Grant's command at Cairo until Halleck arrived, had been the

Academy's Commandant of Cadets, during the period Halleck and Grant were at

West Point, serving in that position from 1838 to 1843. In addition to being at

West Point together, Grant and Smith had been together in Mexico, at the battles of Monterrey, with Taylor's army, and at Mexico City, with Scott's. (Smith

held the rank of colonel in the Regular army and was commissioned a

brigadier-general of volunteers on August 31, 1861.) Halleck had spend the

Mexican war years in California and after it ended, he remained in Northern

California, at Monterey and San Francisco, engaged in law practice and real

estate speculation until the Civil War broke out. As a consequence of this,

Halleck probably was aware of the rough circumstances in which Grant resigned

his army commission while stationed in Humboldt County.

Charles

F. Smith, the brigadier-general commanding the forces at Paducah and Smithland,

independent of Grant's command at Cairo until Halleck arrived, had been the

Academy's Commandant of Cadets, during the period Halleck and Grant were at

West Point, serving in that position from 1838 to 1843. In addition to being at

West Point together, Grant and Smith had been together in Mexico, at the battles of Monterrey, with Taylor's army, and at Mexico City, with Scott's. (Smith

held the rank of colonel in the Regular army and was commissioned a

brigadier-general of volunteers on August 31, 1861.) Halleck had spend the

Mexican war years in California and after it ended, he remained in Northern

California, at Monterey and San Francisco, engaged in law practice and real

estate speculation until the Civil War broke out. As a consequence of this,

Halleck probably was aware of the rough circumstances in which Grant resigned

his army commission while stationed in Humboldt County.

It seems reasonable to conclude from these circumstances that, when Halleck arrived in Missouri and found both Grant and Smith in command, and he began thinking of how to drive the Confederates out of Kentucky, that he naturally preferred Smith to Grant as the commander of the expeditionary forces; this preference, by word and action, it appears Halleck conveyed to Grant—for ten days after Halleck arrived, though he had added Paducah to Grant's district, and thus allowed Smith to come under Grant's command, Grant wrote this line in a letter to his father: "I am somewhat troubled lest I lose my command here."

By January, with Smith's reconnaissance up the Tennessee, to within sight of Fort Henry, followed by the arrival at Cairo of Eads's gunboats, under the command of Flag Officer Foote, Grant was pushing Halleck to allow him to attack Fort Henry. He pestered Halleck with messages about the viability of doing this, and he begged Halleck for an audience to explain his plan. Grant tells what happened—we are to presume—in his memoirs: "The interview was granted, but not graciously. I had not known General Halleck in the old army, not having met him either at West Point or during the Mexican War. I was received with so little cordiality. . . after uttering but a few sentences I was cut short as if my plan was preposterous. I returned to Cairo very much chestfallen." (Grant makes it seem incredulous that Halleck would act so.) Though "chestfallen," Grant wasted no time slamming Halleck again. On January 28th, just a few days after returning from the contentious meeting, he wired Halleck "I can take and hold Fort Henry, if permitted." Supporting him, Foote fired off to Halleck an identical wire.

Halleck was clearly focused on organizing an expedition against Fort Henry and Donelson, if he could find the troops and the money. On January 20, just about the time he dished Grant, Halleck wrote to McClellan:

"I venture to make a few suggestions in regard to the operations in the West. The most feasible plan is to move up the Cumberland and Tennessee, making Nashville the first objective point. This would turn Columbus and force the abandonment of Bowling Green. The line of the Cumberland or Tennessee is the great central line of the Western theater of war."

Soon, Halleck was shifting regiments from other places and building Grant's force up; not because Grant had convinced him of his plan, but because he had come to the independent conclusion that the movement could be successful, that the time to launch it had arrived, and that, if he acted fast, he would be able to take full credit for the success and, perhaps, end up broadening the territorial limits of his department to include Tennessee. In Halleck's mind it seems, Grant was at this time but a pawn while he was the chess master.

HEADQUARTERS DEPARTMENT OF THE OHIO

Louisville, Ky, January 30, 1862

Maj. Gen George B. McClellan, Commanding U.S. Army:

My Dear Friend: General Smith reconnoitered Fort Henry. He says two or three gun boats could go right up there and shell the place out. I believe his suggestion is feasible at this time and I don't hesitate to urge the attempt. The destruction of the bridges and the boats on the Cumberland and Tennessee Rivers is an object of great importance. I have written to General Halleck on this subject and do not hesitate to recommend it for your prompt consideration.

Very Truly, D.C. BUELL

Immediately Halleck shot back!

HEADQUARTERS DEPARTMENT OF MISSOURI

Saint Louis, January 30, 1862

Brig. Gen. D.C. Buell, Louisville, Ky.

I have ordered an advance of our troops on Fort Henry and Donelson. It will be made immediately.

H.W. HALLECK, Major-General

Receiving this, Buell responded, thinking Halleck meant to cooperate with his own advance across the Barren River, driving Johnston toward Nashville: "Please let me know your plan and force and the time etc. Buell"

Halleck replied on January 31: "Movement already ordered. Force about 15,000; and will be reinforced as soon as possible."

To this Buell came back with, "Do you consider active cooperation essential for your success?"

Halleck replied: "cooperation not essential."

It seems obvious what had happened here. Halleck, as shown by his previous communications available to you in the Rebellion Record, had intended to eventually move up the Tennessee River and attack Fort Henry, but only after he had cleared Missouri of Price and McCullough—an operation then actively underway—and then draw enough forces from Missouri to increase Grant's and Smith's forces from 15,000 to 30,000 men, if not more. (This is the amount of men that concentrated finally at Donelson.) But the pace of events made Halleck move quicker with less men: for, once Grant and Foote began pressing him, with Smith's reconnaissance backing them up, and with Buell now raising the issue with McClellan, the general commanding the Army, Halleck realized he had to act fast if he was to get the credit.

And Grant, thus, the next day was on his way. Halleck's strategic thinking, here, was that after Henry fell, he meant to move Grant west toward the line of the Mobile & Ohio Railroad, cutting it, and thus forcing Polk to abandon Columbus; then Halleck would move toward New Madrid and, finally, toward Memphis, leaving Nashville to Buell. Nashville as a strategic point meant nothing to him. He wrote Buell as much. But no sooner had Grant captured Fort Donelson but he was directing not only his own troops but Buell's as well, toward Nashville and this infuriated Halleck to the point he decided to dump Grant and put Smith in his place

Note: How important to the careers of Halleck and Buell that there be success in capturing Donelson is seen in this letter Lincoln wrote to Halleck as Grant's force was being attacked by Pillow's.

EXECUTIVE MANSION

Washington D.C., February 16, 1862

Major-General Halleck,

You have Donelson safe unless Grant shall be overwhelmed from outside; to prevent which I think requires all your skill and Buell's, acting in full cooperation. Columbus will not get at Grant, but Johnson's force at Bowling Green will. (This is Lincoln's "military advisors" talking.) They hold the railroad from Bowling Green to within a few miles of Donelson. It is safe to rely that they will not dare expose Nashville to Buell. A small part of their force can retire slowly toward Nashville, breaking up the railroad as they go, and keep Buell out of that city twenty days. Meanwhile Nashville will be defended by forces from all the South. Our success or failure at Donelson is vastly important, and I beg you to put your soul in the effort.

A. LINCOLN

Lincoln's sentences obscure what he is saying, but the overall effect is to drive home to Halleck that he must cooperate with Buell. The middle part of the message is simply filler to give space for Lincoln to make his point. It seems Lincoln was incapable of simply stating directly what he meant; i.e., "Cooperate with Buell!" The business about what Johnston might do ignores completely the realities of the matter.

Johnston's Real Problem

True, Johnston held the railroad from Bowling Green to within a few miles of Donelson, at the Clarksville Bridge. But Lincoln's statement that "they will not dare expose Nashville" to Buell is silly. As is the idea that "a small part of their force can retire slowly toward Nashville and keep Buell out of Nashville twenty days." The whole tactical problem is that Johnston cannot "retire slowly" from Bowling Green. To do so, implies he has a great force, great enough to detach a force large enough to overwhelm Grant from "outside" as Lincoln states, and, at the same time, hold back Buell for twenty days. It is apparent that Lincoln and his advisors did not know how weak Johnston was. (Here, in the records of both sides' communications, we see, at the outset, that the Confederacy's weaknesses, in manpower and materiel, are so great—relative to the strengths of the Union—that it cannot possibly expect to win the war militarily.)

The only force Johnston has that can be used for this purpose—holding Grant back, long enough to "slowly" retire in front of Buell and "hold Nashville for twenty days"—is the force under the command of Buckner, Floyd, and Pillow, who have taken post at Clarksville, precisely for that purpose.

All Johnston cared about, it appears, was getting his main body away from Bowling Green and Nashville, before Buell could force him into a general battle. It is plain from the undisputed evidence that Johnston left it to the discretion of Floyd and Pillow where they would fight to keep Grant off the line of retreat the main body was rapidly taking toward Nashville. If he is to be criticized by the historians and civil war writers, it must be, because he did not order Floyd and Pillow where to make the necessary stand. But his failure, if that is what it can be called, to order Floyd and Pillow to meet Grant's advance at Clarksville, instead of Donelson, may well have been reasonable: either way it may well be that the defending troops would be lost in the process, unable to disengage and get away wherever the battle was fought.

Apparently, Lincoln's advisors had no idea that the so-called "Kentucky Line" was being defended by two separate forces under separate commanders—Johnston and Polk—with Polk making decisions without regard to Johnston's situation; which meant that there was no way Sidney Johnston could "get at Grant" and keep Buell north of Bowling Green at the same time. Given the weakness of his force at Bowling Green, Johnston knew early on that he could not stand there against Buell, but would have to retreat as soon as Buell could cross the Barren River; and his retreat could not stop at Nashville because the place could not be defended for the same reason.

The amazing thing is that, under such circumstances, Johnston allowed Pillow to talk him into reinforcing Donelson instead of evacuating it before Grant invested it. Johnston could not reasonably have expected the Confederate force, once in place at Donelson, to be able to successfully retreat to Nashville, or if he did think this the basis for it cannot be objectively discerned from the record.

A rational explanation for Johnston's decision to allow Pillow to reinforce Donelson, as stated above, is the fact that he thought he was unable to draw his forces away from Bowling Green and get to Nashville, before Grant, easily overcoming the obstacle of Donelson, could get across his line of retreat. Pillow did hold Donelson for two days, just the amount of time Johnston needed to reach Nashville. Pillow and Floyd could have waited at Clarksville to meet the Union advance from the direction of Donelson, but they still would have apparently been forced to fight a battle, if Johnston's main body was to safely reach Nashville far enough ahead of Buell to get away. So Pillow chose to fight the battle at Donelson instead of Clarksville.

Halleck Tries To Dump Grant

.

No sooner had Grant captured Donelson than Halleck began making efforts to supercede him in command of the field forces on the Cumberland, writing Buell—"I have asked the President to make you a major-general. Come down to the Cumberland and take command. The battle of the West is to be fought in that vicinity. You should be in it as the ranking general in immediate command. Don't hesitate. Come to Clarksville as rapidly as possible. Say that you will come and I will have everything there for you."

The reason for Halleck's reaching out to Buell is clear here. Though Grant had indeed captured Donelson his absence from the field at the time the Confederates attacked his forces almost lost it. As Halleck said, in his message to Buell: "We came within an ace of being defeated. If the reinforcements which I sent down had not reached there on Saturday we should have gone in. (This is not an exaggeration.) A retreat at one time seemed almost inevitable." Buell's date of rank as brigadier-general gave him seniority over Grant.

At the same time as this, taking another tack, Halleck asked McClellan to make Ethan Hitchcock, Lincoln's advisor, a major-general and sent him to the west; Halleck planning here to use Hitchcock to manage affairs at his headquarters while he, himself, took command of Grant's army in the field. Taking yet another tack toward the same result, Halleck reminded McClellan that "it was decided in the Mexican War that regulars outranked volunteers without regard to dates." If this decision were sustained now, Halleck said, it would make everything "right for the Western Division." (Smith, holding Regular army rank as colonel, would be recognized, under the rule, as senior to Grant whose army rank was captain.) On the heels of these messages, Halleck wrote another to McClellan which makes his mind-set crystal clear: Halleck wanted Grant superceded any way he could manage it.

HEADQUARTERS, Saint Louis, February 19, 1862

Major-General McCLELLAN:

Brig.Gen Charles F. Smith, by his coolness and bravery at Fort Donelson when the battle was against us, (not quite) turned the tide and carried the enemy's breastworks. Make him a major-general. You can't get a better one. Honor him for this victory and the whole country will applaud.

H.W. HALLECK, Major-General

Instead, Lincoln made Grant a major-general, with "date of rank" being the date Donelson fell. Hitchcock stayed in Washington and Smith, made a major-general on March 21, remained Grant's junior in rank. Notwithstanding this, Halleck continued to build a basis to move Grant out of the way.

On March 3, he wrote McClellan: "I have had no communication from Grant for more than a week. His army seems to be as much demoralized by the victory of Fort Donelson as was that of the Potomac by the defeat of Bull Run. Satisfied with his victory, he sits down and enjoys it without any regard to the future. C.F. Smith is almost the only officer equal to the emergency." McClellan wired back almost instantly—Do not hesitate to arrest him at once and place C.F. Smith in command." How tenuous sits the crown.

Then came this to McClellan from Halleck.

HEADQUARTERS DEPARTMENT OF THE MISSOURI

Saint Louis, March 4, 1862

Major-General McClellan, Washington