| Read all the Civil War Sesquicentennial articles | Comments and Questions to the Author |

The War in the East, May 1862

I

The Peninsula

Unlike Grant, George McClellan was not a general who moved immediately on the enemy's works. Arriving in front of Yorktown, McClellan's army spent three weeks digging trenches and parallels, roads, bridges, and approaches to the enemy's main batteries located at the east side of the town. These were the most heavily armed and bore on both water and land. McClellan, a fine engineer, built a network of trenches and planted batteries to get to the neck of land between Wormley Creek and the Warwick River reaches. On May 1, 1862, his batteries opened with effect upon the wharf and the town. At the same time as this, the army built roads of logs over the marshes and erected batteries to silence the enemy's guns and drive him from his works at Lee's Mill. During this build-up, the Confederate forces attempted to overrun McClellan's rifle pits edging close to the town, but were repeatedly driven back to their defenses.

Just when McClellan's operations had reached the point of using the heavy Parrott guns, Johnston withdrew his forces in the night and retreated up the Peninsula to another line of entrenchments at Williamsburg.

The morning of May 4, McClellan sent Stoneman's cavalry, with horse artillery, in pursuit, and followed with his infantry. At the same time, he put Franklin's division, which was on boats in the York River, in motion up the river, to disembark on the right bank high enough up to get position to cut off the Confederate retreat.

Skimino Creek Above Williamsburg

The roads the infantry columns moved on converged a short distance in front of a substantial field fortification called Fort Magruder. The fort's parapet was six feet high, the walls nine feet thick and a deep, wide ditch filled with water obstructed access to its front. On either side were a series of redoubts showing forty foot fronts, with rifle pits in between. Here, Johnston made a stand, inflicting some pain on McClellan's lead divisions, but he then abandoned the Williamsburg line in the night and moved on, because Franklin's division, having reached the mouth of the Pamunkey River, was getting into his rear.

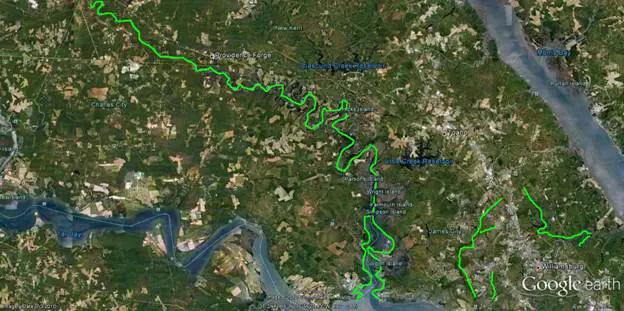

Stoneman, on May 7, followed the Confederate rear guard as far as Providence Forge, then turned to the east and connected with Franklin's division. Over the next several days, in difficult weather, the rest of the Union army moved up and went into camps between Providence Forge and the Lees' White House Plantation situated at the point the York River Railroad crosses the Pamunkey.

Providence Forge

Providence Forge to the White House

On May 12, as the advance of McClellan's army was reaching Providence Forge, the Confederates abandoned Norfolk Navy Yard which required the destruction of the ironclad gunboat Virginia. With the Virginia now gone from the scene, the James River was open to Union navigation and gunboats steamed up it as far as Drewy's Bluff, a few miles below Richmond. There further progress was stopped by the gun batteries commanding a great bend in the river.

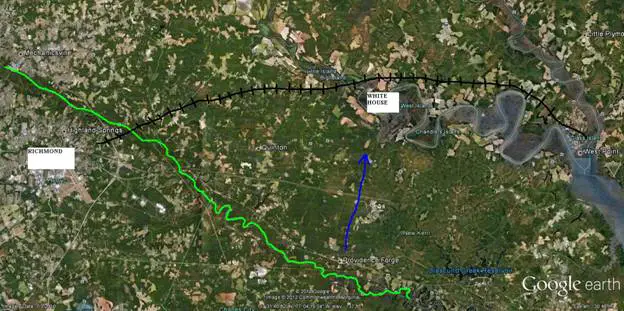

At Providence Forge, McClellan now had two choices: he might move his army southwest, across fifteen miles of slash country, cross the Chickahominy close to its mouth, and take up position at Malvern Hill, using Harrison's Landing as his base of operations; or he might move northeast to the White House Plantation and, using it as his base, move toward Richmond on the line of the York River Railroad. With him at this time was Secretary of State William Seward, who reported to Lincoln what McClellan meant to do next.

Providence Forge, May 14, 1862

ABRAHAM LINCOLN, President

We think that you should order whole or major part of General McDowell's, with Shields, up the York River as soon as possible, and order Whyman's flotilla up the James River. General McClellan moves to White House tomorrow morning.

WM H. SEWARD

Note: Who Seward is referring to as "we" is probably Secretary of Treasury Salmon Chase. Lincoln, Chase, and Stanton had been present in Hampton Road, from May 5 to about May 11. Lincoln did not see McClellan nor did he go ashore. It would have been easy for Chase, or Lincoln for that matter, to have gone by water to the White House and met personally with McClellan.

In his Memoirs (You would have to look at the original manuscript to know whether he wrote it) McClellan takes the position that he first moved to the White House and then, only after reaching there, considered the question which way to approach Richmond. Here is how the memoirs put it.

"Two courses were considered: first, to abandon the line of the York, cross the Chickahominy in the lower part of its course, gain the James, and adopt that as the line of supply; second, to use the railroad from West Point to Richmond as the line of supply, which would oblige us to cross the Chickahominy somewhere north of White Oak Swamp. The army was perfectly placed to adopt either course."

Note: This being published in 1885, just after McClellan's death, it is difficult for a trial lawyer to rely upon the text as proof of the matter stated. The fact is that Mac was, if nothing else, the general commanding the Army of the Potomac in the field. When he reached Providence Forge, knowing at that time that the James River was open, a reasonable person in his shoes would have decided right then, if at all, to turn toward the lower reaches of the Chickahominy, cross that river, and gain the supply route provided by James River. Given other evidence available, it seems reasonable to conclude that he did voice an interest in doing this at that time, but was talked out of it by Seward who was there as Lincoln's mouthpiece. (By May 11, Mac was already moving part of his force by water, from the Yorktown docks up the Pamunkey to White House; the rest marching overland.)

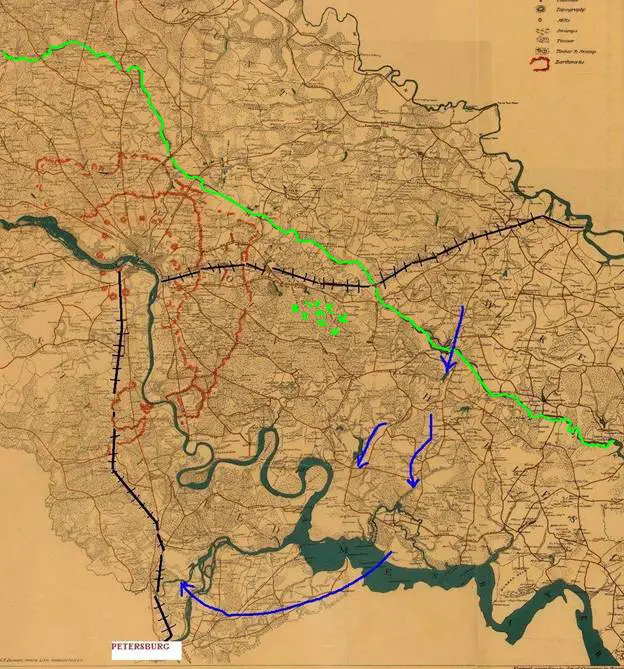

"Making the movement (to James River), the army could have easily crossed the Chickahominy by Jones's bridge, and at Cole's ferry and Barret's ferry by pontoon bridges, while two corps crossed at Long's bridge, covered by White Oak Swamp on their right, and occupied Malvern Hill, ready either to advance upon Richmond by the roads near the left bank of the James, or to cross that river and place itself between Richmond and Petersburg."

Note: Assuming McClellan wrote this, he is suggesting that at or near the time he moved from Providence Forge to White House, he was actually thinking about the idea of crossing James River. As he expressed it, the initial idea was to place the army between Richmond and Petersburg, an idea, given the circumstances, that seems farfetched. The objective would necessarily have to be, to take possession of the Petersburg-Richmond Railroad and move up the railroad (with the city of Petersburg in his rear) to the James River and cross it.

The Approaches to Richmond

There are several reasons why Mac's idea of approaching Richmond from the right bank of the James, as the Memoirs express it, seems unsound: First, Mac would have to occupy Petersburg, for if he did not he would have a large city, defended with fortifications, in his immediate rear; second, he would have to cross James River twice. The first crossing, at Tar Bay, would be covered by the U.S. Navy without much problem, but at the second crossing he would be on his own. Third, his line of communication via the Petersburg-Richmond Railroad would be just as much exposed to an attack in his rear as would the York River Railroad.

Note: That Mac was indeed thinking about the possibility of establishing his base at James River is shown by the fact that, as his front approached the Chickahominy on the line of the York River Railroad, he had sent cavalry to reconnoiter the roads leading to the James and Harrison's Landing.

McClellan's Choice of Base

If he had moved across the James River, one way McClellan might have eliminated the threat to his communications would have been to get possession of the three railroads that come together from the south at Petersburg.

Petersburg Rail Net

In such a campaign, James River would be his base of supply, and he would move west from that point and get on each of the three railroads. But, what effect this would have had upon either Petersburg or Richmond, in 1862, is difficult to fathom. All during the time McClellan was working his forces to get across the southern railroads, supplies would still be reaching Richmond by way of the James River Canal and the Virginia Central Railroad; perhaps, too, supplies might be transported to Richmond on the Orange & Alexandria Railroad. Petersburg could be supplied through Richmond. While these means of Richmond communicating with the South might well have proved in time inadequate to keep the two cities afloat, it would have taken McClellan a long, long time―certainly at least as long as it took Grant to get possession of the three railroads in 1864-65—to starve Richmond into submission.

Thus, it cannot reasonably be denied that, at least from the Union President's point of view, there seemed to be good reason to be concerned for Washington's security, if McClellan put James River between the Union capital and the Army of the Potomac. Lincoln's concern was that, putting James River between the Army of the Potomac and Washington would make it impossible for McClellan to hold the Confederate army at Richmond. Given the relative positions of the two armies, if Mac did that, the Confederate army could easily detach forces from the Richmond defenses to march north and threaten the capture of Washington. How could Mac stop it?

Note: From a strictly professional military point of view, Lincoln's layman's concern for the security of Washington lacked reasonable foundation. If a substantial part of the Confederate army had marched north away from Richmond, McClellan's army probably would have been able to quickly break through the city's defenses. This would have put the Confederates' base of supply in McClellan's hands, and he could then follow them north and sandwich them between his army and the forts of Washington.

Logistics simply would have not allowed the Confederates to do this. They might detach a small force, to operate independently of Richmond, living off the countryside as best it could, but a large force―of sufficient size to seriously threaten the security of Washington—required the support of Richmond as a base.

Without a base, pursued by McClellan, the Confederate army would have been operating at great risk to its own security. To avoid being caught on the Manassas plain, it would have to turn and fight McClellan head on, or march west, cross the Blue Ridge and turn up the Valley, hoping by maneuver to regain its base, or establish a new one at Staunton. In the meantime Richmond is lost and, with it, Virginia.

It is true that, in 1863, the Confederate army did abandon its communications with Richmond and advance northward, but it operated this way for only three weeks, supporting itself off the Pennsylvania farms while avoiding the Washington forts; its objective being to attack the Union army in pursuit.

With McClellan's army approaching Richmond from the direction of the York River Railroad, though, it would be much more difficult for the enemy to do this, since Mac could easily move parallel with such a movement and either cut it off or quickly pursue; either way it is doubtful whether the enemy could get beyond the Rappahannock before Mac brought it to a stand for a battle, either at Hanover Courthouse, Ashland, or the North Anna. If the Confederate force moved north by way of Gordonsville and Culpeper, Mac could get ahead of it by way of Fredericksburg and a general battle would occur on the Manassas plain.

Whether or not the issue of which direction to take in approaching Richmond was actually entertained by McClellan when he was at Providence Forge, or discussed between him and Seward, it was settled when Secretary of War Stanton wired McClellan this.

Washington, May 18, 1862

General:

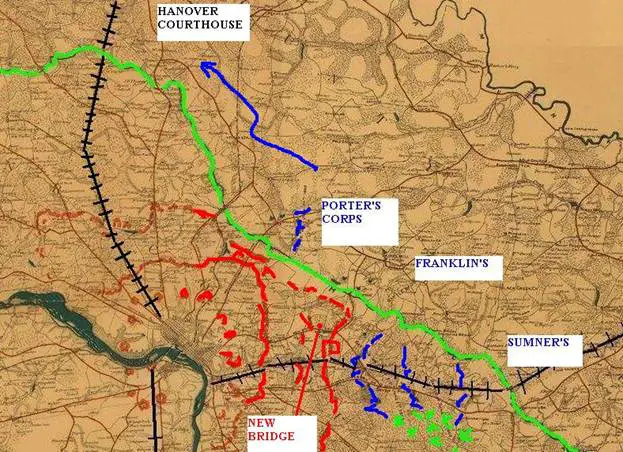

In order to increase your strength, McDowell has been ordered to march upon Richmond by land. He is ordered to keep himself always between Richmond and Washington and so operate as to put his left wing in communication with your right wing, and you are instructed to cooperate by extending your right wing to the north of Richmond. He will move with 40,000 men. And you will give no order which can put him out of position to cover Washington. The President desires that McDowell retain the command of the Department of Rappahannock (which extends to and includes the north suburbs of Richmond) and of the forces with which he moves forward.

EDWIN M. STANTON, Secretary of War

So much for Mac's supposed idea of moving to James River.

Mac was incensed by Stanton's telegraph and rightly so. At the same time Lincoln told Stanton to send this telegram, Henry Halleck was moving at a snail's pace, from Pittsburg Landing to Corinth, a distance of twenty miles. He had with him all of the organized forces in the West—what had been operating in his vast department as three independent armies were now consolidated into one army operating under his command. 125,000 men brought together to laid siege to Corinth under the command of one general.

The situation for Halleck was that of a classic unity of command, but for McClellan Lincoln provided something distinctly different. Lincoln gave McClellan about 80,000 men to capture the Confederate capital while holding back almost 100,000. Fremont had 20,000, Banks had 20,000, McDowell had 40,000, and there were at least another 20,000 manning the Washington defenses, not to mention the regiments in camps at Baltimore, Philadelphia, and Harrisburg.

Now, Lincoln was proposing to allow McClellan the use, sort of, of McDowell's force, if, but only if, he did not try to command McDowell. Whatever order McClellan might give McDowell, and no matter what the circumstances under which the order might be given, McDowell retained the authority―direct from the President—to ignore McClellan. Just an impossible situation. The exigencies of war require that there be one general in command of all the forces committed to a siege operation, otherwise at a critical moment, when unity of action is required, it may not be forthcoming.

II

The Siege of Richmond

It must be wondered why, at this point in time, McClellan did not take a tight-fisted intractable attitude toward Lincoln and either insist that he be relieved of command of the operation, or be given full control of McDowell's troops, to use them as he saw fit. It was simply ridiculous to go on to Richmond with the command arrangement as Lincoln ordered it.

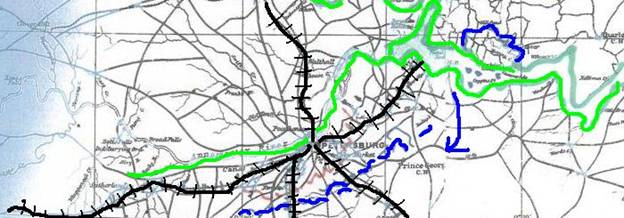

The reason why this is so McClellan well knew. Any Union army that appeared in front of Richmond on the east side of the Chickahominy had no choice but to rely upon the York River Railroad to support its position. The tracks of the railroad, which run fifteen miles from White House to the Chickahominy bridge crossing, would have to be entirely secure, when the front of the Union army began extending itself on the opposite side of the river, or it would be in the situation the Confederate army would be in, if it had cut loose, as Lincoln apparently feared, from Richmond.

The obvious way to prevent the Union army from getting into position on the right bank of the river, to conduct siege warfare tactics that would inevitably lead to Richmond's surrender, was to challenge its possession of the railroad. Forcing it to fight for its communications would make it impossible, unless it was heavily reinforced, for the Union army to simultaneously fight for possession of the right bank of the river. The only way McClellan's army could both defend its communications and operate offensively to gain control of the right bank of the Chickahominy, was to have McDowell's force available to either block any Confederate effort to attack McClellan's right flank and rear, or to attack the attacker's left flank and rear as the battle for the railroad unfolded.

Lincoln's Order Means McDowell cannot Attack The Rebel Force Threatening McClellan's Communications With The White House As That Would Take It

Out of Position to Protect Washington.

Here's how George's Memoirs put the problem:

"The order obliged me to extend and expose my right in order to secure the junction (with McDowell). As it was impossible to get at Richmond without crossing the Chickahominy, I was obliged to divide the army into two parts, separated by that stream."

Note: McClellan is mixing two separate problems. Yes, Lincoln's order certainly required him to extend his right in the direction of McDowell's line of march (Fredericksburg to Richmond), but it was the direction in which the Chickahominy ran that forced him, for a time, to divide his army into two parts, separated by that stream. Until McDowell was actually in the area and subject to Mac's command, Mac had no choice but to leave a substantial force on the left bank of the Chickahominy to guard his right flank and rear.

McClellan Needed McDowell's corps To Do What Porter's corps Did.

McClellan rightly complained to Lincoln about this, but when he did not receive a reasonable response, he should have resigned and walked away from what was in point of military fact a most ridiculous position. Why Mac swallowed the bile and pressed on, escapes intelligence completely. He wrote Lincoln about this but to no avail.

Camp near Tunstall's Station, May 21, 1862

Mr. President:

I regret the state of things as to Gen. McDowell's command. We must beat the enemy in front of Richmond. I most respectfully suggest the policy of your concentrating here by movements by water. I have no idea when McDowell can start, what are his means of transportation, or when he may be expected to reach this vicinity. I regret also the configuration of the Department of Rappahannock. It includes a portion of the city of Richmond. I think that my own department should embrace the entire field of military operations designed for the capture of that city. Further, I do not comprehend your orders. If a junction between McDowell and myself is effected before we occupy Richmond it must necessarily be east of the line Fredericksburg-Richmond and within my department. This fact, my superior rank, and the express language of the Articles of War will place McDowell under my command. Put McDowell under my orders in the ordinary way.

George B. McClellan, General Commanding

For Lincoln's part, it must be said, his mind obviously had not accepted the idea that the capture of Richmond justified his full commitment to McClellan's operation. What was it that drove Lincoln's mind at this time, to refuse to support McClellan with all the Union forces available? Was it truly the issue of security for Washington? Or was it Lincoln's appetite for territory which required spreading his forces to hold it? Or was it something else, politics perhaps?

The paramount criticism of Lincoln's conduct is his use of John Fremont's force of 23,000 men. It simply defies rational explanation, why Lincoln would insist at this time that Fremont take 23,000 men and march them into the Alleghany Mountains. There was no reasonable chance that Fremont might actually be able to move these men south, through the mountain valleys, two hundred miles to Knoxville, much less get them in possession of the Tennessee-Virginia Railroad, because there was no way to supply them.

Assuming Lincoln to have been a reasonably intelligent person, then, we must look for an explanation by identifying a different motive for his behavior than sheer stupidity. History teaches that, in wars generally, governments tend to think first of holding territory as the means of measuring who is winning and who is losing. Western Virginia was Union territory, the argument might have gone, and, therefore, it had to be kept secure; and Fremont's force was in place to do it. Lincoln thought holding territory was more important than capturing the enemy's capital. But, if he actually believed this, he was being stupid, because the capture of Richmond necessarily meant that Virginia, the most important State in the Confederacy, was out of the war.

As with the capture of Corinth, the capture of Richmond, would result in the field of military operations shrinking into the Confederate heartland of Georgia and the midlands of the Carolinas, Alabama and Mississippi. More territory would be gained for the Union, if Richmond was captured than not.

The only reasonable explanation, then, for Lincoln's refusal to fully support McClellan's operations, as he was supporting Henry Halleck's in the West, must be found in the fact that in McClellan's theater of operations, unlike in Halleck's, there was the Union capital.

Rational minds can hardly disagree that the worst thing that could have happened to the Lincoln Government, in its prosecution of the war, was the failure of its naval blockade. From the day he started the war, Lincoln must have known that the only way he could lose it―aside from his generals bungling—was if the Government of Great Britain decided to ignore the Union blockade of Confederate ports. In the spring of 1862, as far as Lincoln could see, there were strong personalities in the majority party controlling the British Government who leaned toward adopting such a policy. If, in this context, Washington were to be occupied by the enemy, even if it were just for a few days, Lincoln had good reason to worry the British Government might seize upon the event as the excuse to force entrance for its commercial fleet into Charleston Harbor. If that happened, it is impossible to doubt, the Confederacy would have gained independence.

General Lee Sees Into Lincoln's Mind

So Lincoln held back 100,000 men from McClellan's command, to make absolutely certain, no matter what might happen, Washington would be safe. Or was it that Lincoln wanted to show Great Britain's government that the Union was clearly well on the way to crushing the resistance of the Confederacy by force of arms. Whichever motive it was, General Lee, President Davis's general-in-chief, understood Lincoln's state of mind completely and played upon it, to save the Confederate capital from the tightening grip of McClellan's brilliant siege operation.

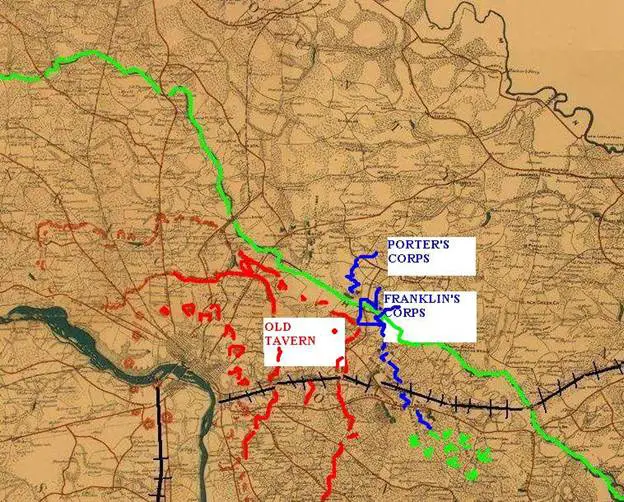

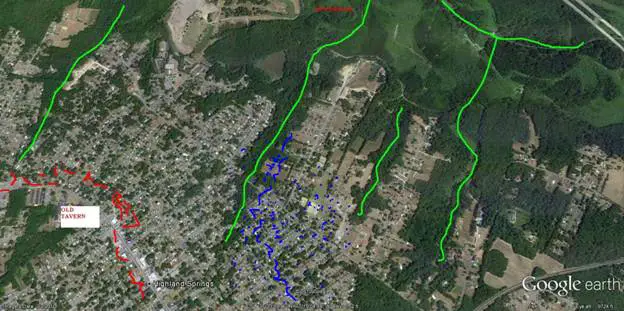

The Key Point, If McClellan Could Gain it, is Old Tavern;

From This Point The Shells From McClellan's 30 pounder Parrott Guns

Can Eventually Demolish The Confederates Outer Lines.

Just as Halleck did at Corinth, and Grant did at Vicksburg,

McClellan Would Dig His Way Right Up To The Rebel Lines

And Then Mount Charges To Break Through.

The challenge for General Lee was how to take advantage of Lincoln's legitimate concern for the security of Washington, as the means of preventing McClellan from getting his right wing across the Chickahominy and gaining possession of Old Tavern. Once McClellan had Old Tavern, Lee would have been put in the position of Beauregard at Corinth and Pemberton at Vicksburg―the enemy horde would be right up against the barricades and it would eventually (whether it took months or a year) become impossible to keep them out.

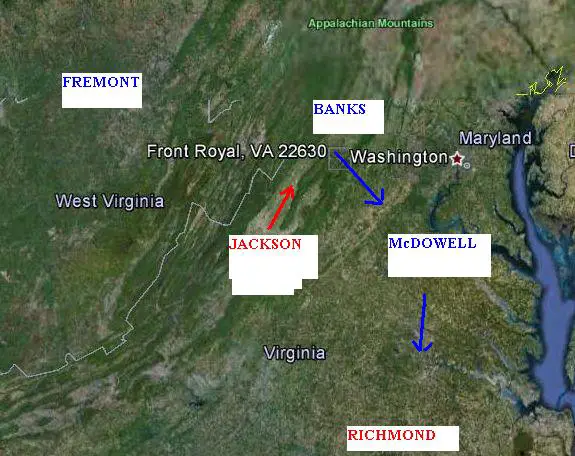

All through May General Lee was working behind the scenes to get the Confederacy's available troops into the best position possible to turn the table on Lincoln. The first thing he did was to organize troops for an offensive through East Tennessee into Kentucky, with the idea of its drawing enemy troops from Virginia. The second thing he did was to reinforce Stonewall Jackson and send him down the Shenandoah Valley to attack Nathaniel Banks at Winchester, to draw McDowell's corps away from Richmond.

Headquarters, Richmond, May 8, 1862

General Joseph E. Johnston, commanding

I understand that the enemy has built a bridge of boats across the Rappahannock opposite Fredericksburg, but has not yet occupied the town, his strength estimated at 15,000 to 20,000.

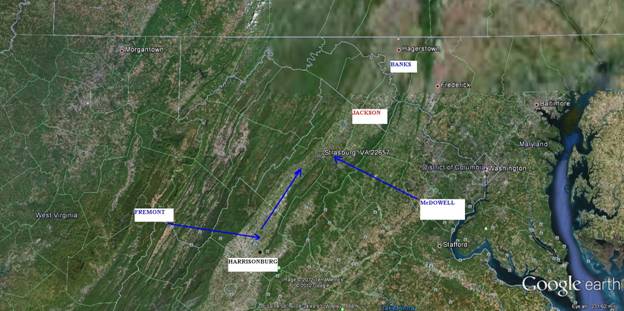

General Ewell at last reports was at Swift Run Gap. General Jackson was at Staunton, with a view of uniting with General Edward Johnson and attacking Fremont's advance, under Milroy, who is not far from Buffalo Gap. General Banks has left Harrisonburg and passed down the valley, his main body being beyond New Market.

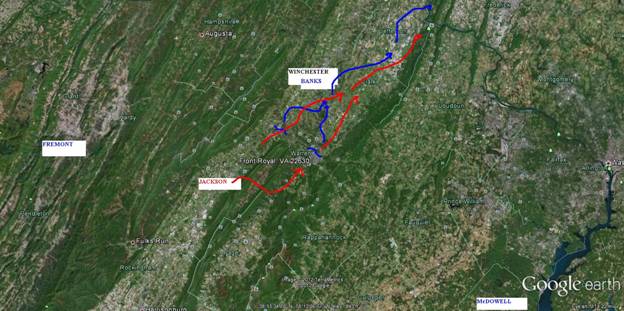

The Situation In The Valley, Early May 1862

It has occurred to me that Banks's object may be to form a junction with General McDowell on the Rappahannock. Two brigades, one from North Carolina and one from Norfolk, have been directed to proceed to Gordonsville, to reinforce that line, which at one time was threatened by a column from Warrenton, the advance of which entered Culpeper Courthouse.

Most Respectfully, your obedient servant,

R.E. Lee, General

Headquarters, Richmond, May 8, 1862

General Thomas J. Jackson:

From the retrograde movement of Banks down the Valley, and his apparent intention to leave it, it is presumed he contemplates a move in the direction of Fredericksburg for the purpose of forming a junction with the column of General McDowell in front of that city. Should it be ascertained that this is his intention, I have suggested to General Ewell the practicability of striking Banks a blow while enroute to Fredericksburg. General Ewell states in his letter that he will not leave Swift Run Gap until the enemy have entirely left the Valley, or until he has orders to that effect from you.

I am respectfully, your obedient servant, R.E. Lee, Genl.

Note: At the time this message was sent, Jackson, in conjunction with Edward Johnson's command, had engaged Fremont's advance at the town of McDowell, causing it to withdraw northward to Fremont's main body which at that time was at the town of Franklin.

Now, Jackson began to press for authority to move again down the Valley, and Lee readily facilitated the movement, at the same time dealing with issues similar to those Lincoln had to deal with regarding McClellan.

Headquarters, New Kent Courthouse, May 9, 1862

General R.E. Lee, C.S.A.

Sir: Longstreet and G.W. Smith are two officers necessary to the preservation of anything like organization in this army. The troops, in addition to the lax discipline of volunteers, are partially discontented at the conscription act and demoralized. Stragglers cover the countryside, and Richmond is no doubt filled with the absent without leave. It has been necessary to divide the army into two parts, one under Smith on one road, the other under Longstreet on another. This army cannot be commanded without these officers; indeed, several more major-generals like them are required to make this an army. It is necessary to unite all our forces now. All that I can control will be concentrated. Nothing is more necessary to us than a distinct understanding of every officer's authority.

Most Respectfully, your obedient servant, J.E. Johnston, General

Headquarters, Richmond, May 10, 1862

General Joseph E. Johnston, General commanding

The enemy has crossed over the Rappahannock at Fredericksburg a regiment, perhaps more. General Patrick, brigade commander at Fredericksburg, reports the enemy's strength there as 40,000 men.

Most Respectfully, R.E.Lee

Richmond, May 12, 1862

General Joseph E. Johnston, commanding Army of Northern Virginia

General: General Jackson is in the valley, General Ewell in the direction of Gordonsville, and General J.R. Anderson, with the troops near Fredericksburg, in the vicinity of that city. General Jackson has been moved to General Edward Johnson, and General Ewell has been called by him to Swift Run Gap.

The enemy is in front of these divisions, and reported to be in greater strength than either. As our troops recede the enemy will naturally follow.

Very Respectfully, R.E. Lee, General

Headquarters, Richmond, May 16, 1862

General Thomas J. Jackson:

Banks has fallen back to Strasburg and the Manassas Gap Railroad is in running order. Banks may intend to move his army to the Manassas Junction and march thence to Fredericksburg. It is very desirable to prevent him from going either to Fredericksburg or to the Peninsula. A successful blow struck at him would delay, if it does not prevent, his moving to either place. General Ewell telegraphed yesterday that in pursuance of orders from you, he was moving down the Valley, and had ordered his troops at Gordonsville to cross the Blue Ridge by way of Madison Court House and Fisher's Gap. Whatever you do against Banks, do it quickly. Create the impression that you design threatening the line of the Potomac.

I am general very respectfully your obedient servant, R.E. Lee General

Move and Countermove

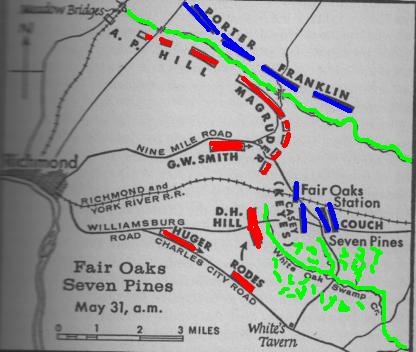

On May 20, McClellan's advance guard—Silas Casey's division of Keyes's corps, marching on the Williamsburg Road, reached the Chickahominy at Bottom's Bridge, ten miles due east of Richmond. Casey's men waded the river and moved forward a mile and began digging fortifications. The next day, more men crossed here, and a mile up the river at the York River Railroad Bridge. On a mile wide front, the Union troops moved westward, about four miles, to the vicinity of Seven Pines, on the Williamsburg Road, and to near Fair Oaks Station, on the railroad. At the same time, conforming to Lincoln's order to reach out to McDowell, who was supposed to be moving southward, McClellan sent Porter's corps to Mechanicsville, five miles up stream from the railroad bridge, with cavalry and a division moving toward Hanover Courthouse. Heintzelman's corps followed Keyes's across the river and the men of the two corps commenced constructing three successive lines of defenses between the north edge of White Oak Swamp and the river.

McClellan's Army Moving Forward Toward Seven Pines

It was now time for action on both sides: McClellan needed McDowell's corps to arrive and cooperate with his evolving siege operation and the Confederates needed Joe Johnston to at least stop Mac's forward progress. To encourage action on Johnston's part, President Davis wrote him a personal letter as McClellan's army was coming up..

Richmond, May 17, 1862

General: There is much determination that the ancient and honored capital of Virginia, now the seat of the Confederate Government, shall not fall into the hands of the enemy. Many say rather let it be a heap of ashes.

To you the defense must be made outside the city. The question is where and how? If the enemy proceed directly here your policy, as you stated it in our last interview, seems to me to require no modification. But, if, as reported here, the enemy should move toward James River you may meet him as he moves. My design is to suggest, not to direct, recognizing the impossibility of any one to decide in advance; and reposing confidently as well on your ability as on your zeal, it is my wish to leave you with the fullest powers to exercise your judgment.

Very respectfully, yours, JEFFERSON DAVISI

Note: How George McClellan would have wished to receive such a letter from his president. For a moment he thought he did, but, instead, he received a great disappointment.

Washington, May 24, 1862

Maj. Gen. G.B. McClellan

I left General McDowell's camp at dark last evening. Shield's command is there, but it is so worn out he cannot move before Monday morning, the 26th. We have so thinned our line to get troops for other places, that it was broken yesterday at Front Royal, putting General Banks in some peril. McDowell and Shields both say they can, and positively will, move Monday morning. You will have command of McDowell after he joins you.

A. Lincoln, President

Note: Lincoln's reference to his "line" being broken hardly carries the weight that it would, if the line broken was the Kentucky Line, or the Tennessee Line. He's talking about the "line" between Strasburg and Front Royal in the Shenandoah Valley, about 80 miles from Washington.

Washington, May 24, at 4:00 p.m.

Maj. Gen. Geo. B. McClellan:

In consequence of General Banks's critical position, I have been compelled to suspend General McDowell's movements to join you. The enemy are making a desperate push upon Harper's Ferry, and we are trying to throw General Fremont's force and part of General McDowell's in their rear.

A. Lincoln, President

With Shield's Division Gone to Fredericksburg, Banks Is Routed,

And Runs For The Potomac. Jackson Occupies Winchester And Sends a Brigade

To The Vicinity Of Harper's Ferry.

Despite strong written objection from General McDowell, Lincoln orders him to march two divisions of his corps to Front Royal, to block Jackson's retreat up the Valley, and he orders Fremont to march to Harrisonburg and down the Valley pike to Strasburg to meet Jackson as he retreats.

Lincoln's Plan To Rid The War of Jackson

Lincoln followed his May 24 message to McClellan with another one on May 25.

Washington, May 25, 1862

Maj. Gen. Geo. B. McClellan:

On the 23rd a rebel force of 10,000 fell upon one of Bank's regiments at Front Royal, destroying it entirely, and pushed on to Winchester. General Banks ran a race with them, beating them into Winchester yesterday evening. This morning a battle ensued, in which Banks was beaten back in full retreat towards the Potomac, and is probably broken up into a total rout. Stripped bare as we are here, I will do all that we can do to prevent them crossing the Potomac at Harper's Ferry or above. McDowell has 20,000 of his forces moving back to Front Royal, and Fremont, who is at Franklin, is moving to Harrisonburg, both these movements intended to get in Jackson's rear. Do the best you can with the forces you have.

A. Lincoln, President

Two hours later Lincoln sent this to McClellan.

Washington, May 25 at 2:00 p.m.

General McClellan:

I think Jackson's movement is a general and concerted one, such as could not be made if he was acting upon the purpose of a very desperate defense of Richmond. I think it is time that you must either attack Richmond or give up the job, and come back to the defense of Washington. Let me hear from you instantly.

A. Lincoln, President

Just amazing. Ten thousand Confederate soldiers have routed Banks's force of similar size, and are marching, it seems, toward the upper Potomac River, having "broken the line" at Strasburg and Front Royal; and because of this Lincoln thinks McClellan's 80,000 soldiers must come back to Washington, instantly? Just amazing! Of course, had Lincoln had Fremont's 23,000 men where they should have been in the first place―at Winchester in the Valley, with Banks at Manassas—Jackson would not have attempted the extremely dangerous endeavor of marching to the Potomac.

There is only one rational explanation for Lincoln's behavior here: the problem was not the fact that Jackson had "broken the line," or that he objectively poised a real threat to the security of Washington―it was the public perception. That is what General Lee expected Lincoln to react to.

The political situation Lincoln was in with Great Britain, in his mind at least, made it impossible for him to simply ignore Jackson's presence in the lower Shenandoah Valley and press McDowell's corps on to join with McClellan. But his second message of May 25 defies explanation entirely; it reveals the mind of a commander-in-chief in very high and irrational excitement indeed. (What role Lincoln's so-called "War Board" played in all this, the record does not say.)

III

The Battle of Seven Pines

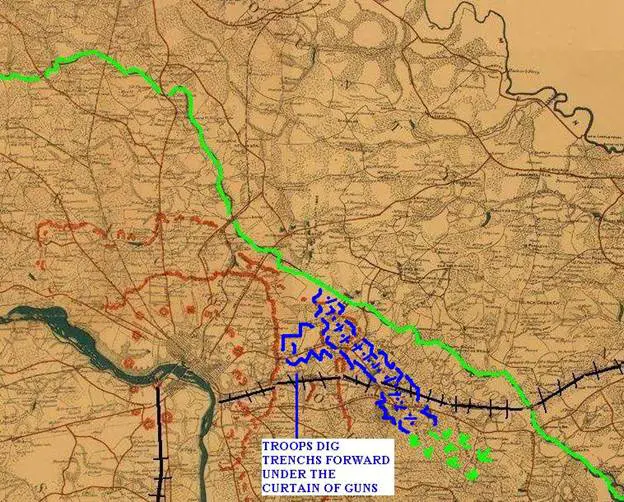

At this time, in an incessant deluge of rain storms, the men of McClellan's army were as busy as a hive of bees; building log roads and ramps across the half mile wide swath of swamp that borders the Chickahominy, building eleven bridges, each a quarter mile from another, along the four miles of river front, from Bottom's Bridge to a point opposite Old Tavern called New Bridge; and building a system of fortifications composed of redans, redoubts, ramparts, and artillery battery lunettes, all the while pushing their lines forward closer and closer toward the counterworks of the Confederates behind Seven Pines.

During the day and night of May 30th a crashing thunderstorm bore down on Richmond, dumping so many inches of rain that torrents of water rushed into the Chickahominy bottomland, flooding the whole range to such an extent that roads became useless and putting the bridges on the verge of being washed away. At this point, Joe Johnston, having waited until the advance of McClellan's left wing was several miles distant from the river, concentrated almost his entire army against the front of Keyes's corps and attacked it in the rain.

.Little Mac was in the saddle, on May 31,

wearily leading Dan Webster into the bottomland opposite the bluffs in front

of Old Tavern. A whooshing wind whipped at the canopy of trees on the slope

behind him, driving a drenching rain squall toward the northwest. As the black

storm clouds barreled by, Mac bent his head under the drooping brim of his

high-crowned hat, and a rivulet of rain water streamed to the ground down the

skirt of his coat. A slight shutter from a malarial fever shook his solid frame. As the

big black stallion paddled through the slush, sniffing the air, McClellan

cupped his forehead in one hand and pressed his fingers against his temples to

repress a feeling of wooziness. Since bringing his army to the Chickahominy, Lincoln's young general had lost his appetite and was racked by dreams in his fitful

sleeps, of dead bodies of his soldiers floating like logs in the swampy ponds

and gullies, clogging the rivulets that streamed into the river.

.Little Mac was in the saddle, on May 31,

wearily leading Dan Webster into the bottomland opposite the bluffs in front

of Old Tavern. A whooshing wind whipped at the canopy of trees on the slope

behind him, driving a drenching rain squall toward the northwest. As the black

storm clouds barreled by, Mac bent his head under the drooping brim of his

high-crowned hat, and a rivulet of rain water streamed to the ground down the

skirt of his coat. A slight shutter from a malarial fever shook his solid frame. As the

big black stallion paddled through the slush, sniffing the air, McClellan

cupped his forehead in one hand and pressed his fingers against his temples to

repress a feeling of wooziness. Since bringing his army to the Chickahominy, Lincoln's young general had lost his appetite and was racked by dreams in his fitful

sleeps, of dead bodies of his soldiers floating like logs in the swampy ponds

and gullies, clogging the rivulets that streamed into the river.

The stallion's tight haunches gave slightly as McClellan led him onto a water-logged knoll beyond the tree line, and reined him to a stop. Feeling the slight pressure of McClellan's bit, Big Dan stood still in water up to his shanks, his roman nose thrust out, nostrils open, rain water dripping from his muzzle. He flicked his pricked ears nervously one way, and then another, until they came sharply forward and froze.

McClellan dropped his hand to his thigh and straightened his body; extending himself in the saddle, he scanned the opposite bank, shrouded in trees and tangled undergrowth, and he listened. Across the river, the storm clouds were moving off, and patches of pale blue were peeking through thin cracks in the steely southeastern sky. The noise of the storm was falling off in the distance, and McClellan could hear clearly now a muffled, rumbling sound, like heavy furniture being dragged across a wooden floor. It was the sound of artillery booming in battery somewhere in the forest across the river.

Turning in the saddle, McClellan looked behind him. A group of horsemen were huddled on an elevation underneath a clump of dripping trees. The French princes were there with two of McClellan's corps commanders. Seeing McClellan raise his hand and beckon, Fitz-John Porter and William Franklin nudged their horses into a walk. Holding their reins high against their chests, the two major-generals guided their horses gingerly down the boggy slope, the plopping hoofs of the animals making sucking noises in the spongy ground.

Throughout the night and into the morning of May 31, rain storms had been raging over the Virginia tidewater. When McClellan arrived at the river bank late in the morning, water, black with iron, was surging out of the Chickahominy's main channel and flooding the wide marshy bottomland of the river basin in confluence with the storm water overflowing the ravines in the surrounding swamps. A hundred yards to the north of where McClellan sat his horse waiting for Porter and Franklin to come up, a corduroy wagon road came out of the forest and ran over the bottomland to the main channel of the river. The road was elevated on an embankment that wound through the swamp from the direction of Gaines Mill, two miles east of the river. A plank bridge, known as the "New Bridge," that spanned the main channel was gone; it was swept away by the morning flood. On the opposite bank beyond the main channel, the road from the New Bridge crossing continued through a series of farm fields which a man named Garnett had cleared from the bottomland. Past the fields, where the slope of the steep bluffs began, the ruts of the wagon road tracked into a ravine in the bluff wall and climbed to the plateau alongside a brawling streamlet which emptied into the Chickahominy basin; reaching the plateau at a point where the thick forest along the rim gave way to more of Garnett's farmland, the road ran a half mile west to intersect with the bend of the Nine Miles Road at Old Tavern.

The Highland Springs Ravine

McClellan's corps commanders sidled their horses to stand on opposite sides of him, as a feathering cascade of rain, dropping from the tail of the last squall like a curtain, moved off beyond the river. Franklin and Porter were West Point classmates of McClellan and they were his only friends in the hellish place he was mired in.

"It sounds like the rascals have engaged with Keyes's front on the Williamsburg Road," McClellan said, when Franklin and Porter rode up.

McClellan gestured toward the gap in the road crossing of the Chickahominy. "If Keyes and Heintzelman can hold their lines across the river, the army might extend its front from their position at Seven Pines on the Williamsburg road, up the Nine Mile road to Old Tavern. Control of the Seven Pines crossroad with the Nine Mile road makes our operations on the York River Railroad secure back at least as far as Tunstall's Station and allows us to unite our whole line two miles closer to Richmond, bring up our heavy guns and push into the city."

Porter and Franklin said nothing as the sound of artillery fire waned and flared and waned again.

McClellan shifted his weight in the saddle and turned toward Franklin on his near side. "Porter must keep his divisions on our right flank facing north, to guard against the enemy trying to get into our rear from the direction of Mechanicsville and Hanover Junction, but, if Sumner crosses his divisions over the Chickahominy on the lower bridges near the York River Railroad, and moves to the north around the rear of Keyes and Heintzelman, can you not get your infantry across the river on that road over there and connect with Sumner's right in the fields between Fair Oaks Station and Old Tavern?

Franklin's mount suddenly snorted and moved sideways several steps, casting its tail against the flies that had risen when the wind and rain died down and were now swarming around its haunches. He leaned forward and touched the animal's neck soothingly, turning him around in a circle to stand still again next to McClellan.

Franklin scanned the gap in the dense timber that lined the far rim of the river bluffs. He could see no sign of activity going on across the river, but he had examined the several ravines that cut into the bluffs with his field glasses the day before, and he had read the reports of his topographical engineers who had studied the enemy's movements on the plateau, from perches in the trees near Fair Oaks. During the last seventy-two hours, the engineers had reported that the enemy was throwing up a maze of earthworks in the two mile space of Richmond suburb known today as Highland Springs. Masses of rebel troops were seen marching, with flying banners and bands blaring, back and forth over the plateau while teams of artillery horses passed through the intervals, pulling cannon into protected positions. The rebel army was plainly giving the invaders notice the ground of Highland Springs was occupied with heavy force.

Shaking his head dourly, Franklin shifted the reins, leading his horse a step closer to McClellan. He pointed at the half-submerged timber posts protruding from the brawling river which marked the location of the New Bridge crossing.

"When the bridge is rebuilt, I think I can get the head of a column over the river," he said; "but, with these rains, the road through those farm fields and up that ravine will be a quagmire. It may be impossible for the men to climb to the rim and even if they can, they must go without artillery. Sumner can use his bridges to get over the river now and connect at a right angle to Keyes's front near Fair Oaks. Then, with Heintzelman's support, he can move up the Nine Mile road on Old Tavern. Once Sumner gets a grip on the plateau beyond Fair Oaks and develops pressure against Secesh's position in front of Old Tavern, my divisions, with their artillery, might follow Sumner across the river, either here or on the lower bridges and also support his attack."

The sound of the cannon was completely gone now, and only the calls of a few water birds could be heard echoing in the river basin. The clearing sky was spreading westward, in the wake of the distant patches of scooting rain squalls.

The three generals sat silently for a time in their saddles. On McClellan's right, Fitz-John Porter sat deep in his saddle, his gleaming eyes scanning the tree line across the river. As Porter listened to Franklin speak, the creases around the corners of his eyes tightened slightly and he rubbed the knuckles of his gloved hand against the bristles of beard on his chin.

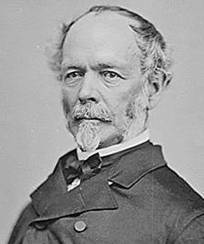

A graduate of the West Point class of 1845,

Porter fought with General Taylor's army at the battle of Buena Vista and he

was with General Scott's army when it landed at Vera Cruz and he had fought in

the breakout battle of Cerro Gordo, at Molino dey Rey and in front of the Belen

Gate at Mexico City. On the narrow causeway in front of the gate, his crew

lying wounded or dead around him, like Grant and Jackson, he had loaded an

eight inch howitzer and repulsed a Mexican infantry charge with canister. After

the war, Porter was an instructor of artillery and post adjutant at West Point during General Lee's tour of duty as superintendent. Immediately after the fall

of Sumter, General Scott had sent Porter to Harrisburg where he organized the

Pennsylvania Reserves. When Scott brought McClellan to Washington, Porter

joined McClellan's training staff. By November 1861, he was in command of a

division and in April 1862 McClellan gave him a corps. Like McClellan,

Fitz-John Porter disdained the politics of radical republicanism and wished

that the war would end with the Union as it was.

A graduate of the West Point class of 1845,

Porter fought with General Taylor's army at the battle of Buena Vista and he

was with General Scott's army when it landed at Vera Cruz and he had fought in

the breakout battle of Cerro Gordo, at Molino dey Rey and in front of the Belen

Gate at Mexico City. On the narrow causeway in front of the gate, his crew

lying wounded or dead around him, like Grant and Jackson, he had loaded an

eight inch howitzer and repulsed a Mexican infantry charge with canister. After

the war, Porter was an instructor of artillery and post adjutant at West Point during General Lee's tour of duty as superintendent. Immediately after the fall

of Sumter, General Scott had sent Porter to Harrisburg where he organized the

Pennsylvania Reserves. When Scott brought McClellan to Washington, Porter

joined McClellan's training staff. By November 1861, he was in command of a

division and in April 1862 McClellan gave him a corps. Like McClellan,

Fitz-John Porter disdained the politics of radical republicanism and wished

that the war would end with the Union as it was.

Porter shifted his seat in the saddle and turned toward McClellan. "Mac, given the ground we now occupy in this hellish place, if you don't fight those people over there for possession of Old Tavern soon, they will soon be fighting me over here for your line of communication with the Lee Place."

In the distance, an eagle glided high in a spiraling ascent in the thermal air over the river. Stroking Dan Webster's long black mane, McClellan's followed the eagle's flight through the sky with his eyes. When it sailed out of sight beyond the trees, he dropped his gaze and looked sullenly across the Chickahominy at the jungly, dark palisades protecting Richmond.

The look on Mac's face was drawn and weary. "For the sake of the cause, Fitz, I dare not risk the safety of this army in making a general attack unless I am certain I can make a sure thing of it." He said.

Before Porter could respond, the silence of the forest was broken suddenly by the crackling rattle of thousands of rifles discharging in unison. Somewhere across the Chickahominy masses of men were volleying.

"Well, gentlemen," McClellan said, "the rain hasn't stopped Secesh from lamming into Keyes. I had better get Sumner across the river before the Chickahominy washes his bridges away."

Seizing the brim of his hat, McClellan swept it off his head and slapped it against his leg; his startled charger pegged sideways a few strides along the swamped knoll. Then he pulled the reins to the left and nudged a blunt spur against the black stallion's flank, and the sleek horse spun round and lunged up the slope, plunging through the ruck in a spray of water.

Franklin and Porter followed McClellan up the slope to solid ground where the trio joined the French princes waiting in the clump of trees, and then, in a bunch, they galloped onto the military road McClellan's pioneers had carved through the Chickahominy wilderness and the horses asked for more bridle and they went hammering over the planks in long driving strides toward Sumner's bridges.

The Ramp From The Grapevine Bridge

* * *

The Confederate army opposing McClellan's advance at Seven Pines was organized into six divisions. Several of these were larger than McClellan's divisions, subdivided into four, five and six brigades instead of three.

General Joe Johnston, the Confederate field

commander, recognized that the army's first imperative was to prevent the enemy

from establishing a line of entrenchments within heavy artillery range of the

perimeter of Richmond. Since 1793, when Napoleon drove the British out of Toulon with artillery, the concentric fire of screened batteries advancing against a

fortified town, to open the way for the sudden, fierce rush of an overwhelming

infantry assault, more often than not secured victory for the attacker. By

1862, with indirect fire of rifled cannon and heavy ordinance, like the massive

Parrott guns, capable of throwing 100 pound shells three thousand yards, Richmond was doomed to capture unless its defenders kept the enemy's big guns out of

range. Therefore, at the very least, the tactical situation McClellan's move to

the Chickahominy had created, required Johnston to formulate a plan of

operation which would arrest, if not reverse, the enemy's advance across the

Chickahominy.

General Joe Johnston, the Confederate field

commander, recognized that the army's first imperative was to prevent the enemy

from establishing a line of entrenchments within heavy artillery range of the

perimeter of Richmond. Since 1793, when Napoleon drove the British out of Toulon with artillery, the concentric fire of screened batteries advancing against a

fortified town, to open the way for the sudden, fierce rush of an overwhelming

infantry assault, more often than not secured victory for the attacker. By

1862, with indirect fire of rifled cannon and heavy ordinance, like the massive

Parrott guns, capable of throwing 100 pound shells three thousand yards, Richmond was doomed to capture unless its defenders kept the enemy's big guns out of

range. Therefore, at the very least, the tactical situation McClellan's move to

the Chickahominy had created, required Johnston to formulate a plan of

operation which would arrest, if not reverse, the enemy's advance across the

Chickahominy.

One plan of operation available to Johnston was to attack McClellan's advancing left wing. After crossing the Chickahominy, the two divisions of Keyes's corps advanced, step by step, toward Seven Pines. Reaching that place on May 24, at about the same time Stonewall Jackson was breaking Lincoln's so-called line at Front Royal, Keyes's men encountered a line of rebel skirmishers and pushed them back a mile, across a farmer's field to the fringe of a swampy forest, now drained and occupied by the Richmond International Airport.

During the next several days, the men of Keyes's two divisions, Casey's in front and Couch's behind, constructed two lines of entrenchments between the edge of White Oak Swamp, on their left, and the intersection of the York River Railroad and the Nine Mile Road at Fair Oaks Station on their right.

White Oak Swamp

Two miles behind the position of Keyes's corps at Seven Pines, down the Williamsburg Road near Savage's Station, Kearney's division of Heintzelman's corps built a third line of entrenchments. A mile farther back, near the Bottom's Bridge crossing of the Chickahominy, Hooker's division built up a defensive position at the edge of White Oak Swamp where it drains into the Chickahominy. Two miles northeast of Keyes's corps, across the Chickahominy river basin, the men of Sumner's corps were building causeways and bridges to span the wide, marshy flatland, and open a wagon road (HW 156) running from Old Cold Harbor six miles to Fair Oaks.

The Old Cold Harbor road snakes south to the Chickahominy on a swell of ground that squeezes between the headwaters of Boatswain's Creek and the marshy fringe of Elder Swamp. In 1862, after crossing the main channel of the river, at Sumner's Grapevine Bridge, the road ran over Golding's farm on the Chickahominy bottomland and up over the open fields of Adam's farm on the Richmond plateau to the intersection of the York River Railroad and the Nine Mile road at Fair Oaks Station.

At the time Keyes began digging in his line at Seven Pines, McClellan's engineers were busy building six trestle and pontoon bridges between New Bridge and Bottom's bridges. Three of these bridges were being built along the front of Sumner's line on the left bank of the Chickahominy. Once the bridges were completed, Sumner could bring his divisions and artillery across the river in three columns and move directly on the sector of ground east of the Nine Mile road between Old Tavern and Fair Oaks. Any attack Johnston might order his army to launch against Keyes, with the objective of driving him back on Heintzelman and pushing both of them back across the Chickahominy, would have a better chance of success if the attack commenced before Sumner's divisions could get across the river.

Another plan of operation open to Johnston was to launch an attack against McClellan's right wing. On May 24, as the men of Casey's division were digging a line of rifle pits in front of Seven Pines and building up an advanced stronghold in front of their center, Fitz-John Porter's cavalry, supported by horse artillery and one infantry brigade, occupied Mechanicsville. Supporting this position, Porter's five remaining brigades took position on the left bank of Beaver Dam Creek. Enclosed by steep banks along a southwesterly two mile course, two converging branches of the stream flow together into the Chickahominy, several hundred yards south of the Mechanicsville bridge.

The ground between the streamlets, about a half mile wide and two miles long, gave McClellan a natural bastion to anchor his extreme right and protect his right rear. A frontal attack against Porter's line along the creek would require the rebel infantry to cross the Chickahominy on rickety bridges, drive Porter's advanced guard out of Mechanicsville and then turn to the southeast. To reach Porter's first line, the rebel assault group would have to go down the steep bank of Beaver Dam Creek under the sweep of enemy rifle and artillery fire, cross over fifty yards of marshy creek bottom and then climb up the opposite bank through a tangle of fallen trees and run up to the enemy's entrenchments. Reaching that point, the attacking force must then hold its position under the fire of Porter's infantry and artillery until reinforcements came up behind to attempt a decisive breakthrough.

The tactical strength of Porter's position at Beaver Dam Creek made it certain that the attacking force would suffer severe casualties with little chance that the sacrifice would result in a successful breakthrough; for even if the rebels broke through Porter's front line, McClellan had the four divisions of Franklin's and Sumner's corps available on the left bank to come quickly to Porter's support.

To lessen the casualty rate of the frontal attack against Porter, and increase its chances of success, it was possible for the rebel infantry columns crossing the Chickahominy above Mechanicsville to march in a wide arc, indirectly heading for McClellan's rear; but the line of march would require the rebel infantry to pass over a steep-banked, narrow stream that rises on the north slope of a gentle ridge in front of Beaver Dam Creek. The stream drains the Topotamomy Swamp into the Pamunkey River to the west, and can only be crossed on two roads which intersect with the Shady Grove Church road on the south side of the swamp.

The Shady Grove Church road (HW 627) runs several miles from the Chickahominy along the crest of this ridge. One of the two roads (HW 301) runs from Hanover Courthouse across the mouth of the Pamunkey, passes Haw's Shop and the swamp and connects with the Shady Grove Church road at a point behind the headwaters of Beaver Dam Creek near Bethesda Church. The other road (HW 643) runs south from the vicinity of Peak's Station on the Virginia Central Railroad, passes Hundley's Corner and Pole Green Church, then it crosses Beaver Dam Creek at its mid point, and continues toward Gaines Mill and Old Cold Harbor four miles away.

Making a flank march across Porter's front, however, would not go undetected by McClellan. Stoneman's cavalry was patrolling on the Shady Grove road, which runs eastward on the crest of the ridge and intersects both the Peak's Station road at Pole Green Church and the Hanover Courthouse road at a point north of Bethesda Church. Stoneman's cavalry squadrons were picketing the two approach roads far in advance of the Shady Church Grove Road. Any attempt by the rebels to move masses of infantry east on the north side of Totopomomy Swamp and swing them south on these roads would quickly be discovered by Stoneman, and the bridges over the Totopomomy stream would be destroyed.

Meanwhile, as the rebel columns marched indirectly for McClellan's rear, Franklin might easily extend Porter's line eastward toward the Pampunky and, as the distance increased between the rebel attacking column and the Chickahominy bridges, McClellan might launch either a general attack against the rebel position at Old Tavern or he might order Porter to seize Mechanicsville; either action might isolate one wing of the rebel army from the other and give McClellan the opportunity to destroy one of them.

Beaver Dam Creek

Furthermore, even if Franklin's corps did not extend Porter's line, McClellan might still develop a general attack against the rebel forces remaining on the right bank of the Chickahominy. Franklin might easily reverse the direction of his front to support Porter's right flank. Like Porter's, Franklin's corps also occupied a bastion-like piece of ground, which was bordered on three sides by a water-filled ditch: on the north, by the wide mouth of Beaver Dam Creek; on the west, by the Chickahominy; and, on the south, by the branches of Powhite Creek.

The eastern fringe of Franklin's ground was cut up by a series of ravines formed by several streamlets that trickled into the headwaters of both Powhite Creek and Beaver Dam Creek. The road from Peak's Station, intersecting the Shady Grove Church Road near Pole Green Church, runs through Franklin's position, and then bends southeast past Powhite Creek and Gaines's mill-ponds; skirting the upper branches of Boatswain's Creek the road runs through Old Cold Harbor. As it passes the mill-ponds, this road intersects the wagon road leading west from Gaines Mill to the New Bridge crossing of the Chickahominy. On the right bank of the river, in 1862, the road bed passed over Garnett's farm fields on the bottomland and, once up on the Richmond plateau, it followed what today is called Lee Avenue where it connects to the Nine Mile road at St. John's Church.

The New Bridge Road leading To Old Tavern

In his advance of the Army of the Potomac from Yorktown to the Richmond suburbs, General McClellan had maneuvered his force into an outstanding tactical position.

The strength of McClellan's tactical position put Joe Johnston in a quandary, where the choice between the available plans of operations entailed great danger to the security of his army. Any rebel advance made indirectly against McClellan's right rear risked not only the development of frontal assaults against the strong defensive positions Porter and Franklin both held, but also the development of a counterattack against the rebel right wing, by Sumner's corps joining Keyes's and Heintzelman's in a push on Old Tavern through the sector of Highland Springs.

In the short run, an attack against McClellan's left flank might gain some temporary success, but, in the long run, only an attack against McClellan's right flank, threatening his line of communication with his tactical base of supply at the Lee Place, had any chance of keeping McClellan away from Richmond.

Since in either case, the rebel army would suffer huge casualties and its organizational strength would be diminished as a result, the hard mathematics of war made the right choice between possible offensive operations clear: if casualties there must be, it was better to absorb them in fighting McClellan's army for its base of supply than fighting to merely push back McClellan's advancing left wing. And yet, the great danger Johnston worried might follow from seizing the initiative made him hesitate.

* * *

In the face of Johnston's textbook tactical

choices, President Davis was as anxious as Lincoln for his field commander to

take the initiative and attack the enemy. Jeff Davis knew that if McClellan's

army forced the Confederate army to abandon Richmond as its base of supply, the

Confederate Government might easily shift its military operations in Virginia

to Petersburg and if forced to move from there, then it might use Lynchburg and

if from there, it might operate from Roanoke or Danville and so on. Indeed,

even if the Confederate army was forced outside the borders of Virginia, and into the midlands of the Confederates States to Atlanta, five hundred miles

away, its strategic base in the Confederate heartland would still allow it to

conduct military operations for years.

In the face of Johnston's textbook tactical

choices, President Davis was as anxious as Lincoln for his field commander to

take the initiative and attack the enemy. Jeff Davis knew that if McClellan's

army forced the Confederate army to abandon Richmond as its base of supply, the

Confederate Government might easily shift its military operations in Virginia

to Petersburg and if forced to move from there, then it might use Lynchburg and

if from there, it might operate from Roanoke or Danville and so on. Indeed,

even if the Confederate army was forced outside the borders of Virginia, and into the midlands of the Confederates States to Atlanta, five hundred miles

away, its strategic base in the Confederate heartland would still allow it to

conduct military operations for years.

But Davis also knew as well as Lincoln that the hard mathematics of war made it clear to every thinking mind that the great disparity between the North and the South, in population and gross national product, would reduce the Southern people to a state of starvation making surrender inevitable. Only if the Confederate States might gain a strong ally among the European powers, would the Davis government have a chance to win a political stalemate with Lincoln's government.

At the moment of McClellan's appearance on the Chickahominy, the British House of Commons was engaged in a hot debate over whether to adopt a resolution, authorizing the Royal Navy to escort convoys of British merchant ships into Charleston Harbor. If Davis lost hold of Richmond, he would lose the State of Virginia to Lincoln, and, with the loss of Virginia, would go the last hope of maritime trade with Britain.

On May 15, when the Confederate forces crossed the Chickahominy from their retreat from the Peninsula, President Davis had ridden out from Richmond, in the company of General Lee, and met with Johnston at his headquarters on the Williamsburg road near Seven Pines.

The three men conferred late into the night, trying to come to a consensus what the Army should do. The conference ended in a desultory fashion, with Davis unable to commit Johnston to a plan of operation. In the following days, as McClellan's five corps came into position on the Chickahominy, Davis, back in Richmond, wrote several letters to Johnston, pressing him to launch an attack against McClellan. Sequestered at his field headquarters near the Chickahominy, Johnston did not reply to Davis's letters and the army remained on the defensive. On May 24, exasperated by Johnston's refusal to take the initiative against McClellan, President Davis called for General Lee to come to his residence on Clay Street.

* * *

In the gray mid-morning of that day, General Lee left his rooms on Franklin Street and walked to the corner of Ninth Street. At the intersection, he crossed Ninth Street and turned up the brick walk, past the old Bell Tower, to Capital Square. Looming above him as he climbed the green temple hill, the statute of George Washington, fixed ramrod straight in the saddle of a trotting bronze horse, was impatiently pointing his ragged rebel army toward Trenton.

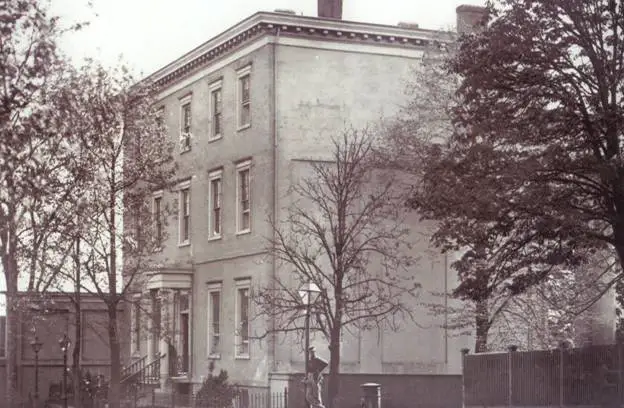

Passing the Capital Building, General Lee reached Broad Street and crossed over to the north side between the wagon traffic and walked east several blocks to Twelfth Street, where he turned up to Clay Street. Two sentries, with long rifles topped with stiletto-like bayonets propped straight up against their right shoulders, were pacing in front of the Davis Residence when General Lee came round the corner and approached. The sentry nearest the iron gate that led to the porch came to attention as General Lee passed through and walked up the steps. At the top of the landing, General Lee raised a large brass knocker on the door and let it fall against the striker.

Immediately the door opened, and a tall Lake Country African, dressed in a white polkadot shirt, with a small white bowtie and black broadcloth coat and trousers, motioned for General Lee to enter. The African's face was the color of obsidian, shiny and deeply creased and immutable, with high cheekbones, impenetrable black eyes and a flat nose; flecks of white colored the tips of the man's wooly hair.

President Davis's War Time Residence In Richmond

As General Lee removed his hat, the African bowed slightly, motioning with the pale copper palm of an upturned hand for General Lee to follow him into the vestibule. The entrance room was round, with a high vaulted ceiling from which hung a bronze chandelier wrapped in black gauze to snare the spring flies. A spiral staircase wound down from the second floor along the wall. "Mr. Davis is in the study," the African said, in a tone of voice that was at once deferential and aloof. The African walked across the room ahead of General Lee, the leather heels of his polished shoes making clicking sounds on the marble floor.

General Lee followed him into a shadowy corridor

and down it to a pair of sliding doors. When the African opened the doors of

the study, a grey light spilled into the corridor from two casement windows

inside. In the center of the room, President Davis was bent over a small,

ornately craved mahogany desk, leafing through a stack of telegrams with a

pained, haggard look on his thin, white face. Hearing the study doors open,

President Davis straightened as he saw General Lee step forward from the

shadows of the corridor and enter the room. "Come in. Come in." Davis said, as he stepped round the desk and clasped General Lee's hand. Behind them, the

African quietly closed the study doors.

General Lee followed him into a shadowy corridor

and down it to a pair of sliding doors. When the African opened the doors of

the study, a grey light spilled into the corridor from two casement windows

inside. In the center of the room, President Davis was bent over a small,

ornately craved mahogany desk, leafing through a stack of telegrams with a

pained, haggard look on his thin, white face. Hearing the study doors open,

President Davis straightened as he saw General Lee step forward from the

shadows of the corridor and enter the room. "Come in. Come in." Davis said, as he stepped round the desk and clasped General Lee's hand. Behind them, the

African quietly closed the study doors.

President Davis drew General Lee toward a thick round table set back in the room under the casement windows. Davis went back to the study desk and began nervously picking through his papers again.

Glancing toward the windows, General Lee laid his hat down on one of the sills and pulled a chair back from the table, positioning it so that one of the narrow shafts of grey light fell over his shoulder; then he sat down, crossed his legs and began reading the several letters Davis brought to the table. The first letter dealt with the status of the few coastal ports still in Confederate control; the second was a letter from Beauregard―Henry Halleck, the Commander of Lincoln's Department of the West, was approaching Corinth from Pittsburg Landing with one hundred thousand men. The third letter was the President's last letter to General Johnston.

As General Lee read through the correspondence, President Davis paced the carpet impatiently; passing back and forth across the patch of light the grey sky threw through the casement windows, Davis's sharp, thin features gave an impression that he was suffering a great fatigue.

Just before the servant opened the study doors to admit General Lee, Davis had been reading and rereading a letter he had received from John Mason, the Confederacy's representative in London; enclosed with the letter was a statement made in debate in the British House of Commons by Lord John Russell, Queen Victoria's Minister for Foreign Affairs.

"The United States Government have now, for more than twelve months, endeavored to maintain a blockade of three thousand miles of coast. This blockade has seriously injured the trade and manufactures of the United Kingdom. Yet her Majesty's Government has never sought to take advantage of the obvious imperfections of this blockade, in order to declare it ineffective. It has, to the loss and detriment of the British nation, scrupulously observed the duties of Great Britain toward a friendly state."

President Davis had rightly read into Russell's statement, ominous news for his government. Since 1861, the great powers of Europe—Britain, France and Russia―had recognized both the United States and the Confederate States as belligerent powers; as such, under the provisions of the 1856 Treaty of Paris, British merchant ships were entitled to enter and exit all of the sea ports of the Confederate States, unless the United States maintained a force "sufficient really to prevent access to the coast of the enemy."

Note: Up to the spring of 1862, the United States Navy had not done this. Instead of attempting to physically blockade the entire coastline of the Confederacy, the Navy stationed its squadrons outside the major ports and intercepted some, but not all, of the many ships attempting to enter the harbors. The Treaty of Paris mandated that if the blockading belligerent state failed to seal access to the small ports as well as the large ones, the neutral states were at liberty to trade with the blockaded belligerent state. If, in the course of such trade, the neutral state's merchant vessels were seized by the blockading belligerent state, the neutral state was at liberty, under the treaty, to use its navy to escort its merchant vessels safely into any port. The Lincoln Government repudiated these provisions of the Treaty of Paris. As a consequence, a fleet of U.S. warships, operating from Key West, and patrolling the sea lanes between the Confederate ports and the West Indies, had been boarding neutral vessels at will and taking them as prizes if military contraband was found.

As the blockade policy of the Lincoln Government unfolded, President Davis had calculated that the British Government would claim the right under the Treaty of Paris to forcibly open full trade with the Confederate States. But Lord Russell's statement made in the House of Commons in the midst of the neutrality debate shocked Davis into recognizing his delusion.

When General Lee had read through the letters and laid them down on the table, President Davis stopped pacing and sat down at the table opposite him. A slight glare from the tall windows fell on the polished surface of the table, and Davis bent his head for a moment. His left eye was covered with a whitish film from a chronic infection and he pressed the palm of his hand against it to counteract the pain throbbing behind it. Then, dropping his hand limply to his lap, as if the force of gravity exerted too great a weight to resist, the Confederate President's chin slumped against his chest and his gaze shifted toward the window.

"Everything goes against us, General Lee." President Davis said. The sound of his voice was dull and muffled and full of despair. "Lincoln has suppressed all resistance to his government in Maryland, Kentucky, Missouri and Tennessee. For a railroad, his congress will soon recognize western Virginia as a new state in the Union. His Western armies occupy most of Arkansas, Louisiana and Tennessee, and Beauregard writes that he cannot hold Corinth and must soon fall back to Tupelo. Lincoln's gun boats dominate the Mississippi River from Memphis to St. Louis, and from New Orleans to Vicksburg. His navy has all of our major sea ports blockaded and, despite her hunger for our cotton, Britain will never send the Royal Navy to force them open."

President Davis's voice trailed off as he peered

into the garden through the casement windows. A row of Elm trees stood at the

back of the garden; behind their green tinged branches, he could see dimly

rising behind them, the pediment peak of the Virginia Statehouse.

President Davis's voice trailed off as he peered

into the garden through the casement windows. A row of Elm trees stood at the

back of the garden; behind their green tinged branches, he could see dimly

rising behind them, the pediment peak of the Virginia Statehouse.

"And now, Lincoln has his army right here in front of Richmond!" Davis said, his voice rising angrily. "Even if Mississippi should fall, the people in Texas and in the midlands of Alabama and Georgia and Carolina will fight on against Lincoln's tyranny; but, if he gains possession of Virginia, he will have cut the heart out of our struggle and the people will resign themselves to surrender."

General Lee did not immediately reply. He sat quietly with one leg crossed over a knee, his hands folded in his lap. The Virginia soldier and the Confederate President sat together at the table for a long time in silence. The faint sound of a distant rumble rippled against the window panes and rain drops began to spatter against the glass and course downward in blurry streaks.

The Confederate President turned back to face General Lee; resting his chin against a bent forefinger, his left elbow on the armrest, he watched the light fall on the profile of General Lee's face: salty black, short-cropped hair, curling back from a broad forehead, intense brown eyes set close to a thick Comanche nose under bushy black eyebrows, full lips and a firm, thrusting chin; Lee's face radiated an expression of cold, quiet confidence.

Davis leaned forward and rested his arms on the table as he gathered a deep breath to speak. "Is there nothing that can be done to drive McClellan away from Richmond?" Davis asked.

Silence pervaded the room again as General Lee still looked away, out the window toward the back of the garden where Jefferson's Roman temple loomed behind the flutes of the Elm trees, his mind silently running, like a tumbler in a gearbox, through the classic textbook examples of siege and maneuver, stretching back before Christ to Alexander at Halicarnassus and Arbela. Drive McClellan away from Richmond? Not likely.

General Lee brought his attention back to the President when Davis spoke again.

"General Johnston must take the offensive against McClellan or he must be replaced with someone who will." The President said.