| Read all the Civil War Sesquicentennial articles | Comments and Questions to the Author |

The War in the West, May 1862

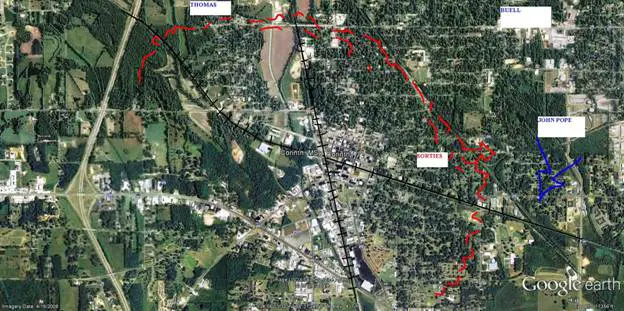

On May 16, 1862, at the same time George McClellan's army was approaching Richmond, †Henry Halleck's army arrived in front of Corinth, Mississippi. Halleck's army, over 100,000 strong, was organized into three army corps, commanded respectively by George Thomas, Carlos Buell, and John Pope. Grant has been shuffled to the sidelines with nothing to do.

Pierre Beauregard's army of 40,000 men, also organized into three corps, these commanded by William Hardee, Braxton Bragg, and Leonidas Polk, occupied five miles of fortifications that formed a cup curving from the northwest to the southeast, covering the junction of the Memphis & Charleston and the Mobile & Ohio Railroads. Earl Van Dorn, with about 5,000 Missouri troops, constituted a reserve force.

The situation presented by the convergence of Halleck's and Beauregard's armies would repeat itself over and over again during the war, illustrating the essence of military strategy of the times: move upon a strategic point the capture of which will deprive the enemy army of a base of operations in a geographic area. If the enemy army stands and fights you for possession of the point, use your superiority in numbers to either destroy it or, by maneuver, force it to give up the point and retreat from the area. Then, once the area served by the base is secure from intrusion by the enemy, move on to the next point and repeat the process until there is no area left that can support the enemy army.

Corinth certainly fits the definition of strategic point in this context: without it, the Confederate Government would not be able to communicate with Memphis and it would have no means of maintaining an army close to the West Tennessee border; its western army would have to fall back into the interior of Mississippi and draw supplies from the railroad crossing the middle of the state, from Jackson, the state capital, to Montgomery, Alabama. This southward movement would leave the strategic point of Vicksburg the next target.

Henry Halleck had two options to choose from, when the advance of his gigantic army came within sight of Beauregard's fortified lines: he could have taken a page from Grant's book at Donelson, and ordered massed frontal attacks to be made immediately against Beauregard's works, or he could order his troops to dig their way up to the rebel works, under the protection of artillery fire, in the classic way of siege warfare. Halleck chose to do the latter, while, at the same time, moving John Pope's army forward to put pressure on the southern edge of the enemy works, threatening to get possession of Beauregard's line of retreat down the Mobile & Ohio Railroad. This decision exposed Halleck to the same public ridicule heaped on George McClellan, but it was the intelligent, professional decision to make, under the circumstances. Like McClellan, Halleck had respect for human life. Furthermore, from a political point of view, it had substantial merit. The Union had just incurred 13,000 casualties at Shiloh and making frontal attacks against Beauregard's lines at Corinth would not only have produced thousands more, but the attacksólaunched without any effort to get the staging area close to the enemy linesówould have been repulsed.

On May 19, 1862, Beauregard wrote to Confederate Adjutant General Samuel Cooper that he thought it "essential to hold Corinth to the last extremity," even "at the risk of defeat," unless "the odds are too great against us." Beauregard, by this time, was the fifth highest ranked general in the Confederate armies. He was an engineer, who had been in command of Confederate forces at Charleston, in April 1861. He had managed the tactical battle at Bull Run, in July 1861, and had assumed command of the field at Shiloh after Sidney Johnston was killed in action. If anyone, besides Lee, was qualified to make an intelligent judgment whether to risk the existence of the Confederate army at Corinth, it was Pierre Beauregard.

What did he do? He first attempted to attack John Pope's armyóHalleck's left wing―but the attacking troops, moving forward during a dark, rainy night, found Pope's front entrenched, with artillery batteries in position behind and abatis in front and Beauregard called off the attack and switched his order to "retreat."

Given the nature of siege warfare, Beauregard might have held the possession of Corinth for several weeks if not for months. It would take Halleck that much time to dig his trenches close enough to the rebel fortifications to justify a massed charge across open space to break through them and seize the place. Even then the massed assaults might be repulsed, with many Union casualties sustained. The whole experience might easily devolve into an effort on Halleck's part, as Grant was forced to do at Petersburg, to dig his way southward and get his army across the railroads which provided Beauregard with his only means of supply. But, if the Confederate army held on that long, the danger was substantially increased that it might not be able to get away.

Despite the fact that the abandonment of Corinth meant that Memphis and Fort Pillow would be lost to the Confederacy, along with any chance of reoccupying Western Tennessee, Beauregard ordered the army to retreat to Tupelo, Mississippi, fifty miles south of Corinth. Beauregard probably made this decision because he knew there was no chance that, if he prolonged the Union siege, sufficient Confederate troops would materialize to either overwhelm the Union forces or drive them away. Given the Davis Government's inability to raise sufficient forces to seriously challenge the presence of Grant's army in front of Vicksburg, in May 1863, Beauregard's assessment of the situation, in May 1862, certainly cannot be characterized as inaccurate.

On May 30, Henry Halleck woke up to the fact that Beauregard's army was suddenly gone from Corinth. At 6:00 a.m., Pope sent him this message: "All very quiet since 4 o'clock. Twenty-six trains left during the night. A succession of loud explosions, followed by dense black smoke in clouds. Everything indicates evacuation and retreat." By 8:00 a.m., Pope's forces were inside the town.

The New York Times

May 31, 1862

Pierre Beauregard was a very sick man at this time, and his sickness may well have played a role in inducing him to give up on Corinth so quickly. But the battle for Corinth had already been fought at Shiloh and he saw no point, under the circumstances, in pretending that it had not. The capture of the railroad crossroads of Corinth was not only another great leap forward for the Lincoln Government in its conquest of the Confederacy but also another example of the inability of the Davis Government to match force to force. Beauregard knew there was no chance that reinforcements would arrive to allow him to take the offensive against the Union forces in his front. That certain fact, above all else, caused him to give up the fort. The list is already growing long nowóJoe Johnston at Centreville and at Yorktown; Buckner, Floyd, and Pillow at Fort Donelson; Nashville abandoned―and now Beauregard at Corinth; and the list will grow longer we know, with Pemberton at Vicksburg, Bragg at Chattanooga and on to the end at Petersburg. Why didn't these people quit?

Joe Ryan

I

II

The War In The West

The Papers of General Grant

III

| Read all the Civil War Sesquicentennial articles | Comments and Questions to the Author |

|

Joe Ryan Original Works @ AmericanCivilWar.com Joe Ryan Video Battlewalks |

|

| About the author: Joe Ryan is a Los Angeles trial lawyer who has traveled the route of the Army of Northern Virginia, from Richmond to Gettysburg, several times. |

||

Battle of Gettysburg

General Robert E. Lee

General JEB Stuart

General Jubal Early

Confederate Commanders

General Joseph Hooker

Union Generals

American Civil War Exhibits

State Battle Maps

Civil War Timeline

Women in the Civil War