Concentration at Gettysburg

|

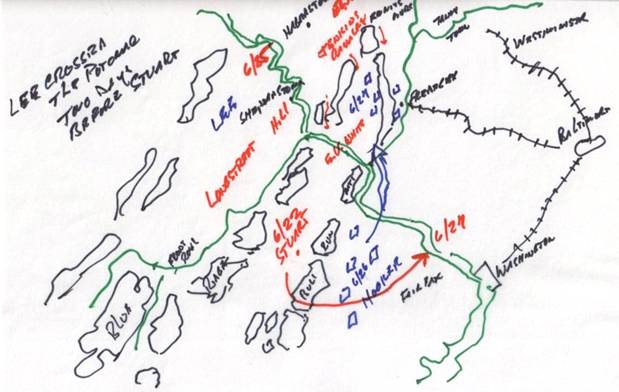

In September 1862, when General Lee and Stonewall Jackson were at Frederick, examining their maps, planning the battle at Sharpsburg, their attention was drawn to Gettysburg. Given the road net and its location relative to Frederick and Washington, they easily could see that Gettysburg was the perfect point upon which to converge for a classic encounter battle. If the Rebel army could be thrown, like a fisherman's net, across the space between the South Mountain and the Susquehanna, reaching as far as Harrisburg to the north, and Wrightsville to the east, the Union army would be induced to conform in order to cover Washington and Baltimore. Conformance, under the circumstance, meant that the Union army would disperse along a 20 mile-long front in the vicinity of the Mason-Dixon line; its objective being, at least in the early stage of operations, to hold its wings in readiness to receive an attack from the direction of Gettysburg and York. As time passed, however, and the enemy did not advance to attack, appearing instead to be standing on the defensive near Gettysburg, the commander of the Union army would be induced by Lincoln’s politics to move, however tentatively, toward Gettysburg—at which point the Rebel army would fall upon the enemy's advance, throw it into retreat, and pursue it to Washington. Lee and Jackson knew that the army was in no condition then, to undertake such a campaign. Its numerical strength was very low, its ranks having been severely depleted by three months of hard fighting and much marching, its supplies all but gone, its animals all but lame. At the moment the army's only choice was to fight somewhere on the defensive or retreat into Virginia. Deciding on the plan of standing on the Antietam against McClellan, the two generals put away their maps and moved the army westward toward the Cumberland Valley and Sharpsburg. Once the Battle of Antietam was over, though, and the army was in front of Winchester, in peaceful camp along the Opequon, General Lee returned to the idea of drawing the enemy into battle at Gettysburg. In early October 1862, he sent JEB Stuart, with his cavalry, on a reconnaissance of the countryside around Gettysburg. On October 9, Stuart, with six hundred troopers, left camp at the old Dandridge place near Bunker Hill and headed for McCoy's Ford in a bend of the Potomac west of Hedgeville. Reaching the ford in the dark morning hours of the 10th, Stuart crossed over into Maryland and headed northwest to Mercersville, circling then to the north, to Chambersburg. At Chambersburg, he turned east and passed through the South Mountain by the Cashtown Gap, drawing topographical maps of the terrain, the water sources, and pastures as he went. At Cashtown, he continued east, crossing the eight miles of rolling countryside between that place and Gettysburg, before turning south toward Fairfield and making his way down the right bank of the Monacacy to White's Ferry at the Potomac. Crossing over, under fire from a Union regiment trying to block the ford, he reported to General Lee, who met him at Leesburg. (In less than forty-eight hours, as he had done in the 50s on the Comanche plains, he rode over 160 miles.)

Stuart's Route

Through the winter of 1862, General Lee developed the plan of operation that would lead his army to the battle of Gettysburg. A.L. Long, Lee's military secretary, and there is no reason to claim he lied, clearly confirms this. Long wrote in 1885: "Lee called me into his tent at Fredericksburg. A map was spread on the table. He said that he might be forced to give battle at Chambersburg or, perhaps, York, but, in his view, the vicinity of Gettysburg was much the best point. In this plan he had a decided object. He was satisfied that the Union army, if defeated in a pitched battle, would be seriously disorganized. . . which would very likely cause the fall of Washington." (A.L.Long, Memoirs of General Lee, p. 268-269 (1885) J.M. Stoddard Co; see also, Walter Taylor, Four Years With General Lee, p. 90-91 (1878 Appleton & Co.) The necessity of his plan of operations Lee made plain to his government. On June 8, 1862, Lee wrote this to Secretary of War Seddon: "There is nothing to be gained by this army remaining quietly on the defensive. . . There is difficulty and hazard in taking the initiative—the enemy must be drawn out in a position to be assailed. It is worth the trial to prevent the catastrophe (of Richmond falling)." And to President Davis, in emphasis, Lee wrote after crossing the Potomac at Williamsport on June 25: "It seems to me that we cannot afford to keep our troops awaiting possible movements of the enemy, but that our true policy is, as far as we can, to employ our own forces as to give occupation to his at points of our selection." (See text at Louis H. Manarin, The Wartime Papers of General Lee, 504, 532. (1961) Little Brown & Co.) Lee’s Movement From VirginiaAfter Stonewall was killed at the battle of Chancellorsville, Lee was forced to suspend his planned movement toward Pennsylvania long enough to reorganize his army into three corps. He divided Jackson's corps into two, putting Jackson's lieutenants—Richard Ewell and A.P. Hill—in command of each and returning Pickett’s division to Longstreet's corps. Each corps now was made up of three divisions, each division composed of ten thousand men. With the Union army in his front, Lee sent Ewell's corps, from Culpeper, on its way toward the Potomac first. Ewell reached the Potomac on June 22 where he received orders to cross and move toward the Susquehanna and Harrisburg. Following behind Ewell came Hill's corps which crossed the Blue Ridge on the 19th and marched down the valley to Sheperdstown. Longstreet's corps, Lee sent north along the east face of the Blue Ridge screened by Stuart's cavalry, which skirmished for several days with Pleasonton's cavalry in the space between the Blue Ridge and the Bull Run Mountains. General Robert E. Lee

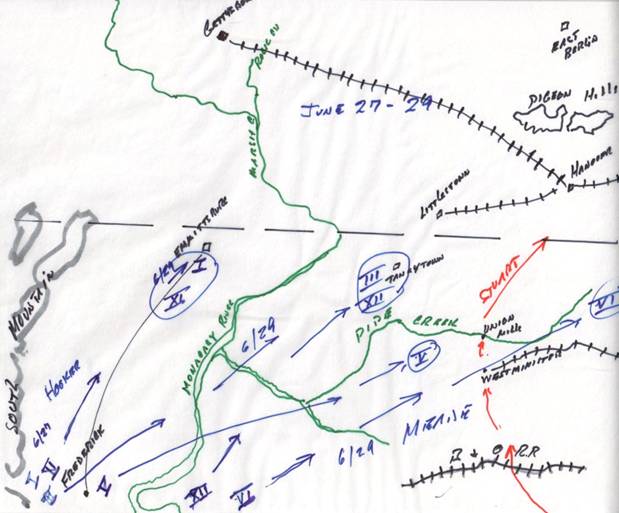

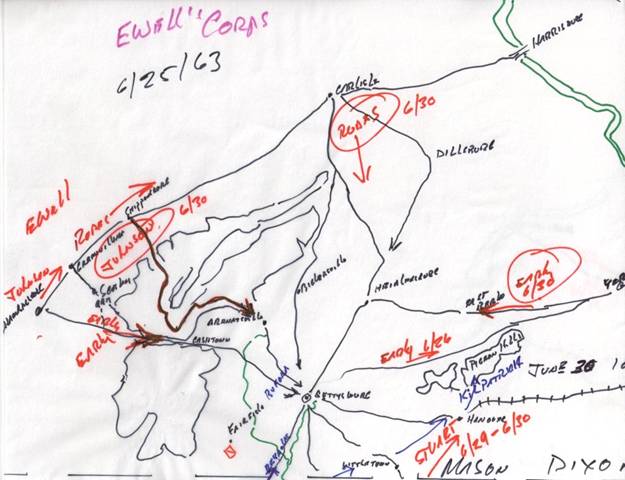

Hooker Conforms By June 23, General Lee was at Berryville in the valley, Ewell was in Maryland marching toward Chambersburg on his way to the Susquehanna, A.P. Hill was reaching the Potomac and Longstreet was crossing the Blue Ridge. And pursuant to Lee’s instructions, Stuart’s was released to move around Hooker’s army as it was moving toward the Potomac, and head for Westminster, Maryland. Once Hooker got into Maryland, he positioned his corps around Frederick and between that place and the South Mountain. By this time, Jubal Early’s division, of Ewell’s corps, had marched north along the west face of the South Mountain and stopped for a time at Boonesboro, the entrance to Turner’s Gap. Union lookouts on the mountain top observed this as well as the whole of Ewell’s corps passing and saw that Ewell was accompanied by a force of cavalry numbering in their estimate five thousand. The cavalry they saw was that of Jenkins’s cavalry which was covering Ewell’s right. Imoden’s cavalry was on Ewell’s left and rear, scouting the Cumberland Valley to the west. E.V. White, a native of both Montgomery County, Maryland, and Loundoun County, Virginia, had his batallion of troopers (Partisan rangers really) on the mountain trails and country lanes observing Hooker’s movements. Joe Hooker The Rebel Army Crossing the Potomac Following Ewell, A.P. Hill crossed the Potomac on the 24th, at Sheperdstown, and followed Early’s route toward Chambersburg. Longstreet followed on the 25th, with Lee, crossing at Williamsport. Meade Takes CommandHooker remained concentrated before Frederick for three days as, first, Early, then Hill, then Longstreet, marched north in the Cumberland Valley past Turner’s Gap. At 1:00 p.m., on June 27, a pivotal day in the campaign, Hooker tendered his resignation to Lincoln. His excuse was that Lincoln had denied him command of the troops at Harper’s Ferry which he wished to use to bolster his own in what he believed would be the decisive battle of the war. At the time Hooker’s resignation was received by Lincoln, General Lee, with Longstreet, had reached Chambersburg, Jubal Early was at York, and Ewell, with Rodes’s division, was at Carlisle. One of Rodes’s brigades was approaching the Susquehanna at Harrisburg while one of Early’s was approaching the Susquehanna at Wrightsville. JEB Stuart, leaving the Bull Run Mountains on the 25th as Lee was crossing the Potomac, had reached the Seneca Falls ford at the Potomac during the night of the 27th, and was across the river moving toward Westminster in the morning. In the dark hours of the morning of June 28, Meade was aroused from his sleep by a courier who brought a dispatch from Henry Halleck, Lincoln’s general-in-chief: “You are in command. Keep in view the fact you are covering Washington. You will, therefore, maneuver and fight in such a manner as to cover the capital and also Baltimore.” Calling his staff, Meade mounted and rode to Hooker’s headquarters. Arriving there at daybreak on the 28th, Meade assumed command. Hooker left without sharing his plans, or giving Meade a clear picture of the location of the army corps. It was at this time, the fact that elements of the Rebel army had appeared on the Susquehanna, at two points—Harrisburg and Wrightsville—came to his attention, just before his telegraph communications with Washington were cut by Stuart’s cavalry riding north toward Westminster. Now, Meade decided, in light of Halleck’s orders, that the Union army must move north and northeastward. George Meade An hour after assuming command of the Union army, Meade sent a courier to Washington with a dispatch for Halleck: “It appears to me that I must move toward the Susquehanna, keeping Washington and Baltimore well covered and if the enemy turns toward Baltimore to give him battle.” Halleck received the dispatch sometime around 1:00 p.m. and sent confirmation of his intention back—“I fully concur.” General Lee’s net had been flung, and the enemy had followed the leads. Meade Conforms For the next forty-eight hours, the six corps of Meade’s army, marching in separate columns, moved toward the Mason-Dixon line, following essentially the line of Pipe Creek. Rising near Manchester in the east, the stream meanders southwestward, past Union Mills and Taneytown to near Emmitsburg where it connects to a tributary of the Monacacy River. Pipe Creek Ewell’s corps on the 30th

General Lee, on the other hand, had no intention of moving to meet Meade at the Mason-Dixon line, at least not yet. Having induced Meade to disperse his concentrated forces along a twenty mile front at the Mason-Dixon line, Lee intended, by holding back his forces, to draw Meade forward piecemeal to Gettysburg, fall suddenly upon Meade’s advance and drive it back, then pushing everything against Meade’s disorganized left wing, turning it, forcing Meade to fall back closer to Washington, if not retreat into the Washington forts. By noon on June 30, Meade, as well as Lincoln, was getting impatient with the absence of Lee from his front. Where was he? What was happening? Meade was unsure. He sent a dispatch to Halleck: “We are as concentrated as we can justify. I have pushed out the cavalry in all directions to feel for the enemy. If they advance against me I must concentrate at that point where they show the strongest force.” At this time, noon on the 30th, John Reynolds, commanding the First Corps, was positioned a little to the north and east of Emmitsburg, behind a creek facing northwest toward Fairfield. Enemy had been spotted occupying that place and it was presumed an attack from that direction would develop soon. “The enemy are evidently marching out,” he wrote Meade, “but whether it is to go to York or give us battle here I don’t know.” From Taneytown, Meade responded to this: “The enemy occupy the Cashtown Gap. Whether this is to prevent our entrance or is their advance against us remains to be seen. With Buford at Gettysburg you might be advised in time of their approach. In case of an advance against you, you must be prepared to fall back and I will reinforce you with Sickles (Third Corps) and Slocum’s (Fifth Corps at Littlestown). If you want to fall back now to Emmitsburg you can do so.” An hour later, mulling the situation over, impatient to find out what was happening in front of him, Meade decided to consolidate his left wing under the command of Reynolds (First, Third and Eleventh Corps) and he ordered Hancock, commanding the Second Corps, to move to Taneytown to take Sickles’s place who he ordered, along with Howard (Eleventh Corps) to support Reynolds. Skyes’s corps (Fifth Corps) at Littlestown, Meade ordered back behind Pipe Creek at Union Mills. The Sixth Corps remained at Manchester. Then the strategic situation suddenly changed. Late in the night of the 30th, Meade received a dispatch from Halleck, informing him that news has reached Washington from Harrisburg that the enemy forces at the Susquehanna had fallen back. Meade thought from this that Lee was now moving to attack him for sure and he ordered Reynolds to creep forward on the Emmitsburg road to meet him; if Lee attacks with a superior force, Meade tells Reynolds, he is to hold Lee back as long as he can and then retreat behind Pipe Creek. At the same time, Meade began to think of attempting to concentrate at Gettysburg, to block Lee’s advance to the Mason-Dixon line, but the numbers, he recognized, were against him. The Sixth Corps, at Manchester, was thirty-five miles away from Gettysburg, the Fifth Corps, at Union Mills, 17 miles, the Second Corps, at Uniontown, 19 miles. Meade still thought of both his wings. Perhaps, the fall back from the Susquehanna would result in Lee appearing on the Westminster Road, seeking to capture Meade’s base of supply. Early on July 1, Reynolds, creeping up the Emmitburg road, with the Eleventh Corps following, decided to take Buford’s place at Seminary Ridge. He writes Meade:”The enemy are advancing in strong force. I fear they will get to the heights behind the town before I can. I will fight them inch by inch, and if driven into the town, will fight them street by street.” Then, as his corps was deploying in line of battle, it was struck in front by A.P. Hill’s corps and the two sides grappled in a clinch and fought fiercely for hours, each feeding in men like sticks to a fire. Suddenly, early in the struggle, as he was directing a brigade into line, a sniper’s bullet slammed into Reynold’s brain, killing him instantly; and command of the Union force fell to Howard who was then arriving with his corps. View East on the Cashtown Road Buford’s View West Toward Cashtown

General Lee’s plan of operations, formed almost a year ago, had brought forth the sublime moment of the coup de grace—just one more hard push with fresh organized troops and the Union retreat will turn into a stampede, the soldiers running pell mell down the roads leading toward the Mason-Dixon line and Meade’s defensive position behind Pipe Creek. At Taneytown, learning of Reynolds’s death, Meade turned to Hancock for help. He told Hancock to turn over his corps to Gibbon and go to the front and take Reynolds’s place and report back what was happening Hancock arrived at Gettysburg about 4:00 p.m. and found Howard and Abner Doubleday frantically digging entrenchments, under fire and pressure from the enemy who were crowding up Cemetery Hill. Showing the two generals Meade’s authority, Hancock took command of the defense. At 4:30 p.m., seeing that Slocum was getting close with the Fifth Corps, he sent Meade word that he thought the hill could not be easily taken. The message ended with, “I leave it to you to decide whether to retreat or hold.” Slocum, learning of this, sent Meade his own message—“Matters do not appear well. I hope the work for the day is nearly over.” At 6:00 p.m., Meade decided the issue, writing Halleck: “Reynolds was killed this morning. I sent Hancock to assume command. The corps are moving up. I see no other course now but to hazard a general battle.” Taking immediately to the saddle, Meade arrived at Gettysburg at midnight. The next day, as the hours dragged into the late afternoon, with the enemy moving in the blurred distance this way and that, he wrote Halleck: “I have concentrated here. The Sixth Corps is just coming in. I am waiting the attack of the enemy.” And it came with a shattering venegence, lasting hours, destroying Sickles’s corps and wedging deep into a widening breach in the midpoint of Cemetery Ridge, almost gaining the Union rear before McGilvery’s battery of artillery, miraculously appearing at the last possible instant, blasted Barksdale’s brigade to atoms. There was one more day of sharp, fierce fighting at the stone wall on Cemetery Ridge. On the Fourth of July, General Lee stood on the defensive, hoping beyond hope that Meade would be stupid enough to take the initiative and attack him, but Meade counted his casualities and his ammunition, and declined Lee’s invitation. He had possession of his communications with Washington, supplies were coming up, and he knew Lee couldn’t stand there forever. The Retreat From Gettysburg

Joe Ryan |

|

Joe Ryan Original Works @ AmericanCivilWar.com |

|

| About the author: Joe Ryan is a Los Angeles trial lawyer who has traveled the route of the Army of Northern Virginia, from Richmond to Gettysburg several times. |

||

Battle of Gettysburg

General Robert E. Lee

General JEB Stuart

General Jubal Early

Confederate Commanders

General Joseph Hooker

Union Generals

American Civil War Exhibits

State Battle Maps

Civil War Timeline

Women in the Civil War