Several

days after Abraham Lincoln's election, in November, 1860, President James

Buchanan gathered the members of his cabinet together in the White House. At

the Cabinet meeting, the President revealed that Governor Gist of South Carolina had written to him, demanding that the Federal Government give up the forts

of the United States in Charleston Harbor. Jeremiah Black of Pennsylvania,

Buchanan's attorney general, reacted negatively to Gist's demand, advising that

General Winfield Scott, the ranking general officer of the Army, should be

ordered to organize a force to be sent to Charleston to reinforce the garrison

there. Lewis Cass of Michigan, the Secretary of State, and Isaac Toucey of Connecticut, the Secretary of the Navy, supported Black's recommendation. The four

remaining members of the Cabinet, John Floyd of Virginia, Secretary of War,

Howell Cobb of Georgia, Secretary of the Treasury, Joseph Holt of Kentucky,

Postmaster General, and Jacob Thompson of Mississippi, Secretary of the

Interior, objected heatedly to the Attorney General's recommendation. They

argued that the Federal Government possessed no power under the Constitution to

coerce South Carolina to remain in the Union, and attempting to hold the forts as

a means to invade South Carolina once she became a foreign power would incite

the entire population of the South.

Listening

to the arguments of his counselors President Buchanan sat quietly in the

cushions of a wheel-back chair beside the fireplace of the Cabinet Room.

Clean-shaven, with a shock of wavy white hair swept up in a pompadour, a

straight nose and bright blue eyes, he was a handsome man for his age. He held

his head tilted to the right, his gaze fixed on the glowing embers dropping

from the burning logs in the fireplace. He couldn't believe it had come to

this: because of Lincoln's election the people of the Slave States were on the

verge of rebellion.

When

the Southerners were finished with their harangue, President Buchanan lifted

his eyes and, glancing at the scowling faces glaring at him from around the

Cabinet Room's large oak table, he said: "But the forts are the property

of the United States and it is my constitutional duty as the Executive to take

care that the forts be preserved and protected."

At

this, his eyes flashing anger, Secretary of War John Floyd got up from the

conference table and walked over to Buchanan, followed by Howell Cobb and Jacob

Thompson.

"It

would be an act of aggression against South Carolina which I cannot be a party

to; I will resign my office before I will sign such an order," Floyd said.

"This

is no time to talk of resignations," the President said, waving a hand in

reply. "We must preserve the government's property; and yet, we must not

encourage South Carolina to go out."

Jeremiah

Black stepped into the group of Southerners and took up a position beside

Buchanan's chair. He placed his hand momentarily on the President's shoulder,

then rested it on the back of the chair. Black was a close friend of Buchanan's.

They were both Pennsylvanians and had cooperated in their political careers

since the days when they were young men.

"It

is not likely that South Carolina will menace the garrison at Charleston just

now. The people in control down there will wait until after an ordinance of

secession is announced," Black said.

The

President looked up at Black. He made a slight nod and turned back to the

Southerners standing shoulder to shoulder in front of him.

Addressing

Floyd, he said: "Let's have no talk of resignations just now. There will

be a time for that. I must at least get the opinion of General Scott as to what

can now be done. In the meantime I want to send an officer down to Charleston to take command of the garrison who we can trust to keep things under

control."

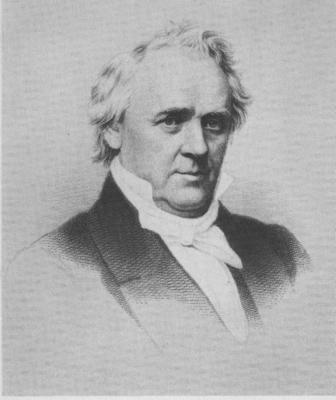

James Buchanan

At

the President's words, the tension in the room lightened a little as the

Southerners flashed each other looks of approval. General Scott was in New York, old and infirm; it would take him time to come down to Washington, and Floyd

could make sure a Southern officer was assigned the garrison's command.

Cass

and Toucey had remained at the conference table when Floyd and the others had

rushed upon the President. Now that the tone of things was lowering, the two

men got up from their seats and quietly joined the others. The Southerners saw

that Buchanan was still occupied in thought and they stood in silence and

waited.

Buchanan

looked up again at Black. "Jere, I want an opinion from you. What is the

President's duty under the Constitution when the people of a State insist on

separating themselves from the Union? I must draft my annual message to

Congress and this question must be addressed." Then he abruptly rose from

his chair and waved the Southerners back to make room for him to pass. They

stepped aside and he went past them to the door and walked alone down the hall.

The

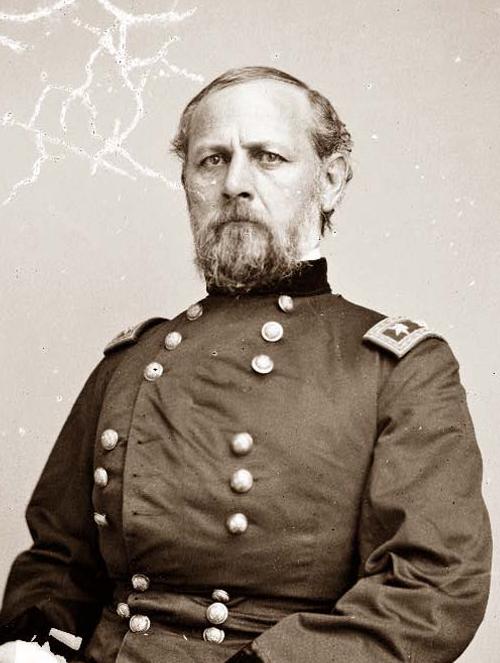

next day Major Robert Anderson left the War Department, under an order signed

by Lt. General Winfield Scott. The order directed him to travel immediately to Charleston, South Carolina and take command of the garrison in possession of the harbor

forts. Anderson was fifty-six. Born in Kentucky into a slaveholding family, Anderson was married to the daughter of a wealthy Georgia slaveholder. Graduated from West Point in 1824, he fought in the Black Hawk War of 1832 and the Seminole War of 1837.

In 1847, he was severely wounded in the War with Mexico, when General Scott's

army attacked the bastion of Molino Del Rey on the outskirts of Mexico City. Later, he became a professor of artillery at West Point where he translated a

French manual on artillery. In 1857, he was promoted to major in the 1st

Artillery Regiment. At the time General Scott called him to duty at Charleston, Major Anderson had been serving with Senator Jefferson Davis on a commission

examining the curriculum of West Point. Anderson would die in Nice, France, at the age of sixty-six.

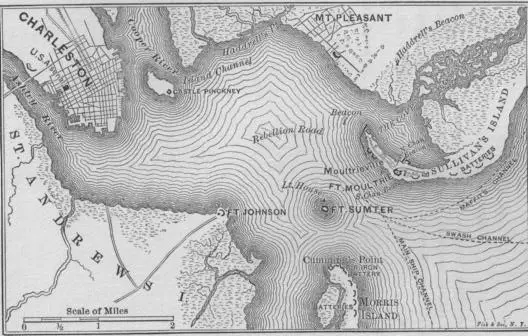

Charleston Harbor Map

With

General Scott's order in hand, Major Anderson boarded a steamer at the

Washington Naval Yard which took him down the Potomac River to Chesapeake Bay and into Hampton Roads. Passing the mouths of the York and James Rivers, the

steamer entered the Elizabeth River and came to rest alongside the Gosport quay. Anderson left the steamer and walked up the pier through a crowd of Negroes

hustling about in a maze of booths operated by tobacco and oyster

merchants;passing beyond the booths, he came to a bridge and crossed over the

river and went into Portsmouth town where he boarded a train of the Seaboard

& Roanoke Railroad bound for Charleston.

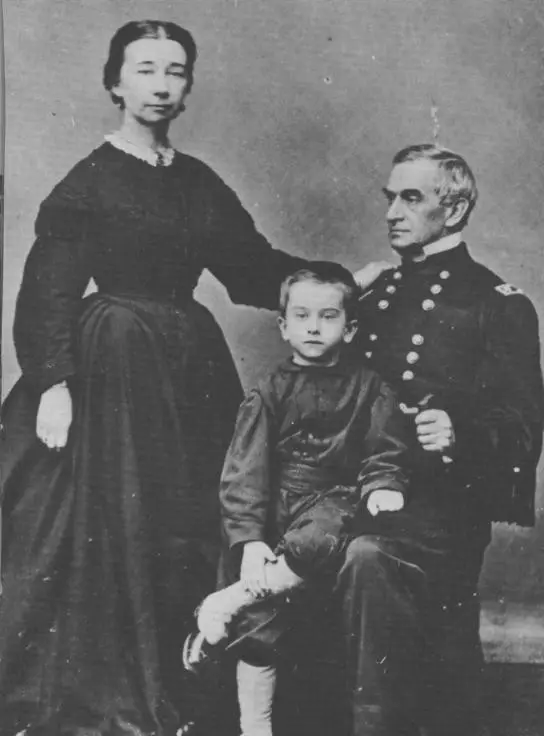

Robert Anderson With Wife and Son

Charleston lies on a peninsula which is bordered on the north by the Cooper River and on the south by the Ashley River. The confluence of the rivers creates a large harbor

that in Anderson's day was the busiest port of the United States on the

southeastern seaboard. Immense quantities of cotton, rice and tobacco were

shipped out of it in exchange for equally immense stores of imports. At the tip

of the peninsula a causeway was built early in Charleston's history which is

known as the Battery. Separated from the Battery by an expanse of open water,

the shore on the southeast side of the harbor is low and sandy, spotted with

patches of green and brown sea grasses. It's continuity is broken up with

creeks which divide the shore into a group of islands and provide passages

between them that can carry small craft out to sea. The two main islands of

this group are called James and Morris Islands. The seaward side of Morris Island is a four mile stretch of sand hills which curl to a point which forms the

southern shoulder of the Charleston Harbor entrance. Northeast of the Battery,

across the wide mouth of the Cooper River, there is another promontory of land

called Mount Pleasant which is also made of sandy soil and divided by creeks

and inlets; to the north beyond Mount Pleasant, the land turns into a line of

sand hills called Sullivan Island which forms a crooked finger at the northern

shoulder of the harbor entrance.

In

1860, there were three United States forts located at Charleston Harbor, Fort Johnson and Fort Sumter inside the harbor, and Fort Moultrie situated on Sullivan Island near the entrance to the harbor. The site of the oldest of these, Fort Johnson, is on the harbor side of James Island on a promontory, some distance inward

from Fort Sumter. The buildings on the grounds of Fort Johnson were originally

built out of logs in 1704 and were in ruins by 1860. In 1811, on the seaward

finger of Sullivan Island, facing the entrance to the harbor, the Federal

Government built Fort Moultrie, comprised of a low scarp wall constructed of

brick. Planted behind the wall, batteries face the main channel of the harbor.

Barracks and a magazine were situated behind the battteries to complete the

fort. Lying directly across the harbor entrance from Fort Moultrie, at a

distance of little more than a mile, is Fort Sumter.

Fort Sumter lays abreast the main shipping channel just inside the harbor mouth, at

Cummings Point at the tip of Morris Island. The fort was designed to shield Charleston Harbor from penetration by an enemy, as happened in 1776 when the British war

ships—Richmond, Romulus and Roebuck—swept through the main

channel into the harbor and bombarded Charleston. Its foundation was built on a

shoal out of broken stones thrown together on top of sand. Begun in 1829,

construction of the fort was completed shortly before Lincoln's election, but

the fort's armament, while present on skids, had not yet been placed in firing

position. Made of Carolina gray brick, with mortar and cement, the fort's walls

begin at the base with a five foot thick scarp wall and rise with a slight

slope 40 feet to the parapets. The walls enclose about an acre of parade ground

and are supported by the arches and piers of three tiers of casements. Brick

barracks large enough to accommodate a garrison of 650 men were built into the

casements and magazines were placed at the corners of the barbetted gorge.

Large iron cisterns for the collection of rain water sat on the parapets.

Fort Sumter in 1860

When

Major Anderson arrived at Charleston, he found two skeleton companies of the

United States Army's First Artillery Regiment occupying Fort Moultrie. The regiment had 61 enlisted men, 7 officers, and 12 musicians present for duty. In

his inspection of the harbor forts, Anderson found that both Fort Johnson and Fort Moultrie were too dilapidated to provide a secure base of operations. The

barrack buildings at Fort Johnson were falling down and, at Fort Moultrie, the

walls were broken by large cracks and wind blown sand was piled up to the

parapet. Worsening the situation was the fact that a town had grown up around Fort Moultrie and some of its buildings were close to the walls of the fort and towered

over them.

Concerned

to place his garrison in as strong a defensive position as possible, Major

Anderson rode a schooner to the dock of the United States Arsenal on the Ashley River and approached the Arsenal's commanding officer, Colonel Benjamin Huger. Major

Anderson presented Huger with a written requisition for 100 rifles and 40,000

rounds of ammunition. Colonel Huger told Anderson that he could not grant the

requisition, explaining that Anderson's predecessor had attempted to obtain a

similar requisition but Secretary Floyd refused to approve it. When Anderson insisted that the requisition be honored, Huger promised to telegraph the War

Department in Washington, asking for instructions. Anderson accompanied Huger

to the telegraph office and followed Huger's message with his own addressed to

the secretary. In his message, Anderson explained that the activities of the

Carolinians around Fort Moultrie constituted a threat to the security of his

command which required reinforcements of men and material. The messages sent, Anderson returned to Fort Moultrie to await Floyd's response.

A

week later, on December 6th, Captain Don Carlos Buell, an Assistant Adjutant

General at the War Department, arrived in Charleston and met with Anderson at Fort Moultrie. Buell told Anderson that when Floyd received the telegraph

messages he and Huger had sent, a cabinet meeting was held with President

Buchanan. In the meeting, based on advice he received from General Scott, the

President initially took the position that troops must be sent to reinforce Anderson; but Floyd, Thompson and Cobb insisted that Governor Gist of South Carolina had

promised them that no attack would be made against Anderson's garrison unless

the Federal Government attempted to reinforce it. The three Southerners warned

Buchanan that if reinforcements were sent to Anderson, the Gulf States would

immediately go out of the Union in mass. At this point, Secretary of State

Floyd suggested that the President wait until the War Department had time to

send an officer down to Charleston to assess Anderson's immediate needs and

report back. The President agreed to this, and Floyd sent Buell off to Charleston. President

Buchanan. In the meeting, based on advice he received from General Scott, the

President initially took the position that troops must be sent to reinforce Anderson; but Floyd, Thompson and Cobb insisted that Governor Gist of South Carolina had

promised them that no attack would be made against Anderson's garrison unless

the Federal Government attempted to reinforce it. The three Southerners warned

Buchanan that if reinforcements were sent to Anderson, the Gulf States would

immediately go out of the Union in mass. At this point, Secretary of State

Floyd suggested that the President wait until the War Department had time to

send an officer down to Charleston to assess Anderson's immediate needs and

report back. The President agreed to this, and Floyd sent Buell off to Charleston.

Captain

Buell spent most of December 6th inspecting Fort Moultrie and the surrounding

terrain. The following day he visited Charleston and spoke with Governor Gist

and Colonel Huger. When he returned to Fort Moultrie in the afternoon he met

privately with Major Anderson on board the garrison's harbor schooner.

Reasoning that Floyd might approve an order of operations couched in terms of

the garrison's ability to defend itself, Captain Buell and Major Anderson

drafted this proposed order: "Whenever you have evidence of a design to

proceed to attack any one of the forts, you may defend by placing your command

in either of them."

The

evidence of such a design, both soldiers agreed, was already all around Fort Moultrie: the riflemen in the buildings of the town, the batteries being built in the

sand hills surrounding the fort and the schooners patrolling the channel

between Fort Moultrie and Fort Sumter were sufficient to show a design to

eventually attack the garrison. Thus, once the order was issued by the War

Department, Anderson might exercise his discretion to shift the garrison's

location to Sumter at any time.

Captain

Buell left Charleston, by train, late in the evening of December 7th and

arrived at Washington early the following morning. At 9:00 a.m., he found Floyd at his desk at the War Department getting ready to leave for a cabinet

meeting at the White House. On the way out the door, Floyd stopped in the

hallway and hurriedly read the paper Buell handed him; without asking Buell any

questions, Floyd scrawled his signature across the bottom of the order and

returned it to Buell as he went on to the stairwell and left the building.

In

Buell's absence from Washington, Buchanan's cabinet began to fall apart.

Lawrence Keitt and several of his associates, all congressmen from South Carolina, learning of Buell's mission to Charleston, had an audience with the

President on December 6th. They told Buchanan that Governor Pickens, who had

replaced Gist, was willing to agree that South Carolina would not attack Anderson's garrison before the State Convention passed an ordinance of secession, but

Pickens would not allow Anderson to be reinforced. Buchanan refused to discuss

the issue with them unless they first presented Pickens's proposal in writing.

Shortly after the Keitt crowd left the White House, Buchanan was handed a

letter from Howell Cobb the Secretary of the Treasury. The letter informed

Buchanan that Cobb had resigned his cabinet position and was already gone from Washington and on his way back to Georgia.

Several

days later, Keitt and the other Carolinians from Congress came back to the

White House and showed the President a memorandum they had drawn up for his

signature. When Buchanan saw that the memorandum called for an agreement that

no reinforcements would be sent to Charleston, he angrily told the Carolinians

that he would sign nothing and pledge nothing regarding the status of the

harbor forts. In the middle of the conference with the congressmen, Senator

Slidell of Louisiana burst into the meeting room. Slidell was an old political

friend of Buchanan and someone Buchanan had counted on for support. Slidell became incensed when Keitt told him that Buchanan would not sign the memorandum.

The discussion rapidly broke down into argument between Buchanan and Slidell over the power of the President, under the Constitution, to enforce the laws of

the United States in a state on the verge of secession. Buchanan called Slidell a traitor and told him to get out of the White House. But when Keitt and the

others began to follow Slidell out of the room, Buchanan lost heart and waved

them back. He told them that he would keep their memorandum until such time

that he decided to change the status quo in Charleston.

Mollified

by this, Slidell and the Carolinians left the White House and returned to the

Capitol where Congress was in session. Later in the day, Lewis Cass, the

Secretary of State, hearing of Slidell's confrontation with Buchanan, came to

the White House to see the President. Cass demanded that the President

immediately order troops to Charleston to reinforce Anderson. When Buchanan

refused to do so, Cass tendered his resignation and stormed out.

At

the other end of Pennsylvania Avenue events were just as chaotic. In the House,

the Republican congressmen were in a panic over the looming reality of

disunion. Suddenly, who was right and who was wrong on the slavery question meant

nothing to them. John Sherman, the Republican from Ohio who have caused a

prolonged fight over the speakership the year before, proposed an immediate

division of all the territories of the United States, between the Slave States

and the Free States. John Cochrane of New York proposed that the Constitution

be amended to recognize slavery in the territories below the 36/30 line of the

Missouri Compromise. Noell of Missouri proposed a constitutional amendment

dividing the Union into three sections with three executives. All of these

resolutions were referred to a Select Committee which united behind a

resolution affirming the necessity of providing the Slave States with

additional constitutional security against threats to their peculiar property.

At

the same time, in the Senate, John Crittenden of Kentucky offered resolutions

that proposed constitutional amendments guaranteeing protection for slavery in

the territories and in the Slave States. The Senate referred the Crittenden

resolutions to a select committee which included John Breckinridge, the Vice

President, Jefferson Davis of Mississippi, Robert Toombs of Georgia, Stephen

Douglas and William Seward. After much procedural wrangling, the committees of

both houses approved a resolution calling on the legislatures of the States to

ratify a 13th amendment to the Constitution of the United States which stated

that, slavery where it existed could never be abolished by an act of Congress.

The proposed amendment was eventually approved by a two thirds vote of both

houses under Article V of the Constitution, but by then the States were already

at war.

In

the afternoon of December 20, 1860, with two vacancies in his cabinet, the

Congress in chaos and the country in confusion, President Buchanan left the

White House dressed in a tuxedo and wearing a white tie. His niece, Miss Harriet Lane, wearing a golden satin gown, her plump rosy face framed by chestnut hair

stiffened with bandoline, accompanied him. They rode in a carriage drawn by two

gray horses several blocks up New York Avenue to Mrs. Parker's mansion. It was

the day the President was to give away the bride at the wedding of Mrs.

Parker's daughter to congressman J.E. Bouligny of Louisiana.

When

the carriage arrived at the Parker mansion and the President and Miss Lane

entered the large foyer, they passed through a throng of ladies wearing gowns

similar to Miss Lane's; the flounced gowns laid over enormous hoops which, with

their heads loaded with garlands of flowers that trailed down their dresses to

the floor, made the ladies look like bells. As the ladies made way for the

President and Miss Lane to pass, two Negroes dressed in black livery blew

trumpets which blared the refrain of "Hail to the Chief."

The

mansion had been converted into a conservatory for the occasion; groups of live

plants and shrubbery filled the spaces between the cushioned arm chairs, sofas

and tables. Fountains stood in the hallways between the parlors and were filled

with blossoming roses and lilies brought from Florida. In the dinning room,

which connected to the main parlor, a long table of cedar and ivory encrusted

with jewels was covered with roast beef and turkey, duck, chicken, fried and

stewed oysters, jellies, whips, candied oranges and a variety of pies, cakes

and puddings. On a side board servants were filling long slender glasses with Champagne. The damask drapes which hung on valences over the tall narrow windows of the

parlors and dinning room were closed; leaving the rooms lit only by mellow gas

light which flickered and hissed.

Reaching

the main parlor, where a crimson velvet curtain was stretched across the other

end of the room, the President paused in the doorway and spoke a few words to

the Rev. Mr. James of St. John's church who was to officiate at the ceremony,

and then he sat down heavily in an arm chair just inside the door. He crossed

his legs and placed one arm on the arm rest of the chair and lowered his head

slightly to the side, nodding for the wedding guests to enter the room and

arrange themselves along the walls. When the rustling of dresses and murmuring

of the guests had finally faded into silence, the clergyman stepped forward and

pulled a cord which caused the velvet curtain to open and the bridal party

appeared in position behind it. The ladies in the wedding party gasped with

delight and clapped as the bride and groom stepped forward to the center of the

room.

Suddenly,

just as the bride and groom began exchanging their vows, a great commotion was

heard in the entrance hall. A group of young men wearing blue cockades and red

sashes came through the rooms toward the wedding party, stomping and leaping

into the air in their leather riding boots and shaking hands with the ladies

and clapping the backs of the gentlemen they encountered. Lawrence Keitt, the Carolina congressman, was at the head of the pack. When he reached the parlor door and saw

the flushed faces of the bride and groom at the other end of the room, he shook

a paper in his fist.

"Thank

God! Thank God!" Keitt exclaimed.

The

Rev. James held out his hand to quiet the congressman. "Mr. Keitt, Mr.

Keitt, are you crazy?"

"No

by God, No! South Carolina has seceded, Sir. Here's the telegram!" Keitt

said as the ladies and gentlemen in the room swarmed around him, laughing and

clapping their hands.

As

this was happening, Miss Harriet Lane, left standing alone, nudged her way

around the clamoring throng and came to the side of the President's chair. In

the time it had taken Keitt to gleefully read the telegram aloud, the

President's rosy complexion changed to a pasty hue. The day he had been

dreading had finally come. The egg shell had cracked. The old Union he had

spent his entire political life serving as congressman, senator, cabinet

minister, diplomat and president, was shattering on his watch.

Seeing

the despair registering on her uncle's face, Miss Harriet Lane looked toward

the servants who were silently standing in the hallway, eyes and mouths agog.

Impatiently, she shook at them a long white handkerchief attached by a chain to

a ring on her index finger. "May we have the President's carriage?"

She said in a trembling voice. Then, as several servants hurried off toward the

entrance hall, she reached for her uncle's arm and the two of them walked

unnoticed out of Mrs. Parker's parlor.

In

Charleston Harbor, several days later, a detail of men from Major Anderson's

garrison brought a string of wagons out of Fort Moultrie and pulled them a

quarter of a mile through the little town of Moultrieville and the sand hills,

to a sea wall where three schooners were tied up to barges. For several hours

during the afternoon, the men loaded boxes and trunks onto the barges. Then

when the work was done, the men went abroad the schooners and, with the barges

trailing behind them, they drifted the schooners into the harbor channel on the

incoming tide. Major Anderson had informed the Charleston harbor master that

the schooners would be carrying the personal possessions of his soldiers'

families, from Fort Moultrie across the harbor to Fort Johnson. Anderson explained that he intended to use the buildings there to house his soldiers’

wives and other noncombatants. The schooners sailed across the harbor in thirty

minutes and set anchor in front of James Island across from the Battery.

At

sundown, while the schooners lay on their anchors off James Island, the artillery men still at Fort Moultrie appeared at the sea wall with their officers

and climbed into a string of row boats. While a rear guard remained in the

fort, the men rowed toward Fort Sumter across the waters of the harbor in the

twilight. A small paddle boat used to patrol the harbor approached within a

hundred yards of the row boats and slowed its engine but came no closer. The

little flotilla continued on until it reached Fort Sumter's wharf at the base of

the gorge wall. As soon as they reached the wharf and began to moor the boats,

the men attached bayonets to their muskets and scrambled out on to the

esplanade and raced for the sally port where a group of stone masons were

lounging.

As

they ran, someone's angry voice rang out: "What are these soldiers doing

here?" The civilian laborers realized too late that it was Anderson's men.

When

the string of running soldiers reached the civilians they pushed them forward

into the sally port tunnel and past two sets of open iron gates and out onto

the parade ground. The soldiers bringing up the rear passed through the tunnel

and spread out to roust the rest of the laborers out of the casement barracks

and secure the fort. Once this was done, Major Anderson went up to the parapet

on the salient wall and lit a blue light as a signal to the rear guard at Fort Moultrie. Shortly, a gun boomed and the schooners lying off Fort Johnson immediately

raised anchor and sailed across the harbor to the wharf. As soon as the the

signal gun sounded, the rear guard spiked the cannon that had covered the

garrison's movement across the harbor, broke up and burned the gun carriages

and wagons and cut down the flag staff. At Fort Sumter, meanwhile, Anderson's men set to work unloading the food and munitions supplies in the boxes lashed

down on the barges and the stone masons were ordered into the row boats. One of

the schooners then cut loose from the barges, sailed over to Fort Moultrie and picked up the men who had stayed behind and brought them back to Sumter.

During

the entire movement of Anderson's men to Fort Sumter, the Carolinians remained

amazingly quiet. Given their control of the land and sea surrounding Fort Moultrie, they had plenty of warning that Anderson was organizing his garrison for a

movement to Fort Sumter. The schooners were chartered from local owners and

their captains were Carolinians. The use of the row boats had to be purchased

and their placement behind the sea wall was easily observable from both land

and sea. When the barges were being loaded at the sea wall by Anderson's men in

the early afternoon, the South Carolina battery crews and the riflemen in the

town buildings around the fort could easily have interfered with the operation.

Given the several hours of observation available to those in the harbor patrol

boats and those in the batteries and town buildings around the fort, the

Carolinians had to recognize early on that Fort Sumter was the object of Anderson's operations. Yet they fired none of their guns at Anderson's men and the harbor

patrol did not interfere with the row boats. They knew their little state was

out in the cold alone and not ready to attack the armed forces of so great a

power as the U.S.A.

Fort Sumter was the bridge between peace and war, between political conflict within the Union and war between foreign nations. When the news of Anderson's movement reached Washington those Southern gentlemen still present at the Capital flew into a rage. Keitt’s

crowd of Carolinians, accompanied by John Floyd and Jefferson Davis, stormed

into the White House. Ushered into the presence of President Buchanan, they

demanded an explanation why he had not returned the memorandum they had left

earlier with him before allowing Anderson to change the status quo. "You

all know it is against my policy to exacerbate the situation down there,"

the surpised President said.

The

Southerners pressed around Buchanan, each taking a turn at trying to cajole him

into ordering Anderson's men out of Charleston Harbor altogether; they argued

that Anderson's presence was threatening war; that it was angering the other

Slave States and that no peaceful solution to South Carolina's secession could

be negotiated as long as Anderson remained.

Turning

from one to the other, the flustered President refused to be forced into

concession. "You are pressing me too rudely, Gentlemen," he said.

"You don't give me time to say my prayers."

Keitt

replied harshly to the President: "You promised there would be no change

without notification. If you don't get those men out of Sumter South Carolina will!"

The

President shook his head as Keitt spoke and, getting up from his chair, he

walked toward the door. "Tomorrow, Gentlemen. Come back tomorrow and the

government will answer you. I will meet with the cabinet and we will

decide."

When

the President convened a cabinet meeting that night, there were new faces among

the President's advisors. Jeremiah Black, the President's old friend from Pennsylvania, had assumed the office of Secretary of State which Cass had vacated several

weeks earlier. Phillip Thomas of Maryland had entered the Cabinet as Secretary

of the Treasury in place of Howell Cobb of Georgia. Edwin Stanton, an arrogant

bald-headed lawyer from Pennsylvania, had taken Black's old place as Attorney

General.

Secretary

of War Floyd opened the meeting by loudly insisting that Major Anderson had

moved to Fort Sumter without orders and should be called back to Washington for a court martial.

Black

angrily rejected Floyd's assertion that Anderson had acted improperly. "Anderson acted in precise accordance with his orders," Black said.

"He

did not!" Floyd retorted.

Abruptly

Stanton cut in: "Where are his orders? Show us his orders!"

Floyd

fumbled among a sheaf of papers he had brought into the room and found Buell's

paper that he had signed. Floyd's eyebrows raised and his lips tightened as he

read the words, "you may defend by placing your men in either of

them." Floyd threw Buell's paper down on the conference table and pointed

a finger insolently at the President.

"Major

Anderson had no cause to move; the garrison was not attacked. I understood you

to say to the congressmen from South Carolina that the government would do

nothing without giving fair warning. You must order Anderson back to Moultrie or out of the harbor altogether or there will be war!"

As

Floyd spoke, Jeremiah Black grabbed the paper from the table and he and Stanton

walked off toward a corner. When Black read the text and recognized Floyd's

scrawled signature, he turned back and stood between the President and Floyd.

"You are proposing treason!" He shouted.

Now,

Floyd was trembling with rage, and he thrust himself bodily toward Black. Their

eyes inches apart, the two men glared at each other, their hands balled into fists.

"Gentlemen,

Gentlemen," the President said: "Please compose yourselves. It's

nobody's fault that Major Anderson has acted as he has. In any event it's too

late now to order him back, isn't it? South Carolina now occupies Fort Moultrie."

Hearing

this, Floyd snapped back: "Then I must resign from your cabinet,

Sir."

The

President's expression hardened and he looked Floyd steadily in the eyes.

"Well Sir, go then, go, go as you wish."

The

angry Virginian hesitated a moment; looking around at each of Buchanan's

ministers his eyes came to rest on Jacob Thompson of Mississippi. He expected

Thompson to speak up and support his view of the situation but Thompson

remained silent. Then he stormed out of the room.

When

Floyd had gone from the cabinet room, the President walked over to his arm

chair in front of the fire place and sat down heavily with a sigh. In the

silence that followed Floyd's departure, the ministers sat quietly around the

conference table and waited for the President to speak.

When

he finally broke the silence, the President kept his face turned toward the

flames licking at the logs burning in the fire place.

"Is

it necessary that we keep a garrison in the harbor down there? After all there

is much reason in the argument that South Carolina ceded the sites of the forts

to the United States solely to provide for the defense of its harbor; not to

provide the Federal Government with the means to blockade it."

Turning

his face toward Jeremiah Black, the President said: "Have you not looked

at those old laws, Jere?"

Before

Black could respond to Buchanan, the harsh voice of Stanton echoed through the

room.

"Ordering

the garrison out of the harbor would be as treasonous as Benedict Arnold's

giving up West Point to the British in 1780," Stanton said.

The

President raised his hands to warn Stanton to stop. Like Floyd's, Stanton's words stung Buchanan to his core; but he wanted no more ministers that night to

go.

"Oh

no, Stanton! Not so bad as that. . . it would be not so bad as that," he

sarcastically replied.

The

next day, a messenger appeared at the house on K Street where Keitt and his

friends were staying, and handed him a letter from the President. When Keitt

opened the letter, he found that the President had rejected South Carolina's

demands. "I am urged immediately to withdraw the troops from the harbor at

Charleston. . . This I will not do. Such an idea was never thought of by me

in any possible contingency." The President wrote.

That

night a mob appeared in K Street and banged tin plates together and rang cow

bells into the late hours to let the South Carolinians know that Major Anderson

had become "our Bob," and overnight was now a hero to the people of

the North.

On

New Year's Day, 1861, Keitt and the Southern congressmen still in Washington appeared at a reception at the White House, wearing the blue cockade secession

badge. Keitt refused to shake hands with the President as he passed through the

reception line. The Northern congressmen arrived at the reception, wearing red,

white and blue ribbons on their sleeves. Later, Buchanan disappeared up the

stairs of the White House and went into a private conference with General

Scott, who had arrived from New York. After a long discussion, with Scott,

President Buchanan ordered the 25 gun sloop, U.S.S. Brooklyn, to Charleston Harbor, but, a few hours later, reflecting on his constitutional powers, he

rescinded it. He knew that sending a battleship of the United States, to

enforce the will of the Federal Government over the whole people of a State, is

a plain act of war; for, called by its right name, a President's order sending

a battleship to Charleston was hardly any different than the King George

sending his fleet there in 1776. It was a manifestation of a government's

exercise of raw power against a de facto State for the purpose of subjugating

her people to its will.

Instead

of the U.S. Brooklyn, the President now decided, the government would

send a civilian ship with supplies. Receiving this new order, General Scott

leased the sidewheel merchant steamer, S.S. Star of the West, on January 4, 1861, and put Captain McGowan of the U.S. Navy in command. Putting munitions,

supplies, and 250 soldiers on board, Scott ordered McGowan to attempt a

peaceful entry into Charleston Harbor.

On

January 9, in the dawning light, the crew of a vessel on guard duty at the

mouth of Charleston Harbor saw the Star of the West come up the main

channel toward the bar and set off rockets as signals to the gun batteries in

place around the Harbor perimeter. As this vessel retired into the harbor;

following, the Star of the West steamed round the shoals and swung in an

arc to approach Fort Sumter. As it did this, a battery in the sand hills near

Cummings Point fired solid shot at her. The first shot whizzed past the

pilothouse and masts but the ship continued on; a shot struck the ship aft the

fore rigging and stove in some planking; another shot careened off the stern

narrowly missing the rudder. Still the Star of the West kept steaming

on. A gun opened on her from Fort Moultrie, but the range was too great for the

caliber and the shot fell far short of its mark.

When

he heard the sound of the Carolinians' gun on Sullivan Island, Anderson ordered the long roll beaten and his men hustled to their posts at the cannon.

Then, with his second in command, Abner Doubleday at his side, he climbed to

the parapet and scanned the approaching vessel with binoculars. By Anderson's side, Doubleday sighted the ensign of the Star of the West and requested

permission to open fire on the Carolinian battery firing from Sullivan Island.

Shaking

his head "No," Anderson motioned to Doubleday to follow him and they

walked over to the terrace behind the parapet of the sea flank wall and

disappeared out of sight of their men into a casement room. Soon the

engineering officer, Captain J.G. Foster, joined the two officers in the room

and the three hurriedly discussed whether the order should be given. Captain

Foster was adamant that the guns of Sumter should be used against the

Carolinians. Gesticulating toward the south, he said excitely to Anderson: "That battery over there has fired the first gun, now that the war is

opened we should return fire."

"No,

Captain, We shall not return the fire," Major Anderson replied; "my

orders are to act strictly in defense of this fort. The Star of the West is a civilian ship. When those people fire their guns on us here in the fort or

on our warships at sea then the war is opened."

By

this time the Star of the West had changed direction inside the harbor

mouth and was steaming toward the flank wall of the fort. The only damage the Star

of the West had so far sustained from the cannon fire was some splintered

planks on the foredeck and a broken railing on the stern. The situation looked

for a moment as if the Star of the West might easily cover the half-mile

span of water between the harbor mouth and Sumter's wharf, but then two vessels

came from the middle ground of the harbor and approached the starboard side of

the Star of the West. One of these vessels, dragging behind her a

schooner, was approaching on a line which threatened an impact between the

trailing schooner and the Star of the West. Recognizing the danger of

losing all hands in a collision, Captain McGowan ordered the helmsman to

continue the vessel in her port turn so that she came full circle and steamed

back toward the harbor mouth and toward open sea.

Before

the Star of the West was back across over the bar, running back to New

York City, its mission aborted, the State of Mississippi had declared its

independence from the Union; the next day, Florida declared it was out of the

Union; the day after that, Alabama announced its secession; Georgia followed

suit six days later. On January 26, Louisiana joined them, followed, in

February, by Texas and Arkansas. South Carolina was no longer out in the cold

alone against so great a power as the United States.

Written by: Joe Ryan |