| Read all the Civil War Sesquicentennial articles | Comments and Questions to the Author |

The Battle Of Gaines Mill

Abraham Lincoln went into the Telegraph Office and rummaged through the telegrams that were stacked in the in-coming message trays and found the latest telegram from McClellan.

|

Edwin Stanton New Bridge June 25, 6:15 p.m.

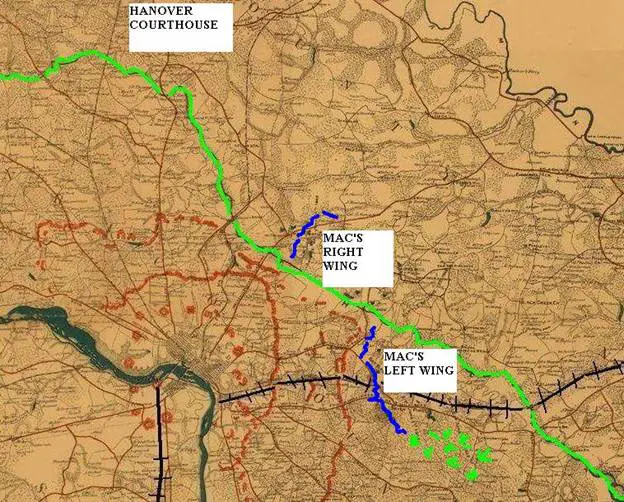

Several contraband just in give information that Jackson's force is at or near Hanover Courthouse. I incline to think that Jackson will attack my right and rear. This Army will do all in the power of men to hold their position and repulse any attack. I regret my great inferiority in numbers but feel that I am in no way responsible for it as I have not failed to represent repeatedly the necessity of reinforcements, that this is the decisive point, and that all the available means of the Government should be concentrated here. If the result of the action which will probably occur tomorrow is a disaster the responsibility cannot be thrown on my shoulders—it must rest where it belongs.

I feel there is no use in my again asking for reinforcements.

G.B. McClellan, Major General |

Lincoln took several angry strides toward a large map that hung on the office wall. He scanned it, looking for Hanover Courthouse; finding it, he looked again at McClellan's telegraph.

Lincoln frowned and sat down heavily in a chair by the telegrapher's desk. An expression of uncertainty settled on his face as General Scott's parting words, uttered so many months ago, came back to him. There is still time. He thought of the list of troops he had just made. King's division was at Fredericksburg. It could board the steamers at Acquia Creek and be with McClellan by sundown tomorrow. Ricketts could be down there in another day.

No, he thought; sending King to McClellan would mean that the line of the Rappahannock could easily be breached, bringing Washington within a day's march of that phantom, Stonewall Jackson. If, in fact, Jackson was now at Hanover Courthouse, he could march north as King's division was embarking for Fort Monroe. This seemed highly unlikely, but if the Confederates were to break into Washington and burn the place, the country would be thrown into a panic and Britain might seize upon the event to break the Union's blockade of Southern ports.This was the persistent fear clouding Lincoln's vision, it bubbled like a pool of oil in his mind, making it impossible for him to take any risk, however slight, that Washington might be lost..

And he had already

made up his mind McClellan had to go. McClellan was too young, too haughty, in

action too timid—a fencer not a thrasher—and his politics and his friends were

wrong. Six months ago McClellan was an asset when Lincoln needed the support of

the Democrats and the army organized, but now it was operating in the field and

the Republicans held the majority in Congress, and Lincoln's comprehension of

the nature of the war was changing. Yes, enough of McClellan and his cronies.

Time to get them out and the Army in the hands of the Republicans.Lincoln rose

from his seat and headed for Stanton's door. Finally, he thought, McClellan will

have to fight.

And he had already

made up his mind McClellan had to go. McClellan was too young, too haughty, in

action too timid—a fencer not a thrasher—and his politics and his friends were

wrong. Six months ago McClellan was an asset when Lincoln needed the support of

the Democrats and the army organized, but now it was operating in the field and

the Republicans held the majority in Congress, and Lincoln's comprehension of

the nature of the war was changing. Yes, enough of McClellan and his cronies.

Time to get them out and the Army in the hands of the Republicans.Lincoln rose

from his seat and headed for Stanton's door. Finally, he thought, McClellan will

have to fight.

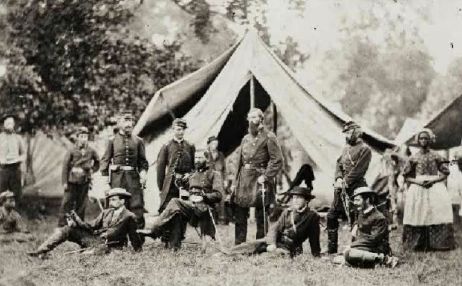

It was close to midnight when McClellan came down the road leading from Gaines Mill and the Grapevine Bridge, and veered Big Dan into Porter's camp ground behind Beaver Dam Creek. He had been in the saddle almost sixteen hours. He was tired, hungry, and his clothes were disheveled. Leading Big Dan through the camp he came down a row of tents into a clearing and dismounted in front of Porter's headquarters.

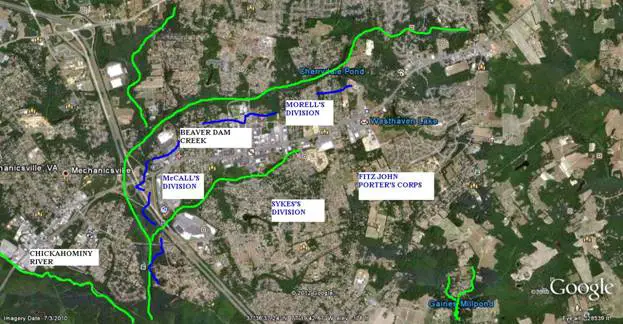

Beaver Dam Creek

Under a tent fly propped on poles, Fitz John Porter was conferring with several staff officers when he saw McClellan. He broke off the conversation and went outside. "Hallo, George," he said, clapping McClellan on the shoulder and tugging him toward the tent.

McClellan resisted the pull; turning back to Big Dan he removed a saddle bag and looked around. "Fitz, let me get this dust off first. "Where can I clean up?"

Porter pointed to a table that stood at the far side of the clearing. There were several buckets of water on the table and a stack of towels. "Over there, George. I'll be here when you're ready to talk."

McClellan walked across the clearing to the table. Taking off his shirt, he soaked one of the towels in a bucket and swabbed his face and upper body with it. He was shorter in height than the average man, but broad-chested with a hard abdomen and narrow hips. In his youth his family called him "Little Mac" and this is the name the men in the ranks favored. Putting the towel down, he opened the flap of his saddle bag and removed a clean shirt and put it on. As he tucked the shirttail into his trousers, he started to walk toward Porter's tent, but midway across the clearing he changed his mind and sauntered up the tent row until he came to Porter's telegraph station.

Several orderlies were sitting on a bench outside the tent and they jumped up when they recognized it was McClellan. Inside, a junior officer, looking up from a table he was working at, got quickly to his feet and stood at attention as McClellan entered. McClellan saw behind the officer a civilian telegrapher busy at his key. Signing to the officer to go back to his work, McClellan passed him with a pat on the shoulder and approached the telegrapher and stood at his side. After a moment, the telegrapher noticed McClellan and, with a look of surprise on his face, stopped tapping the key.

"Can you send a message to Washington for me," McClellan said in a polite voice, almost a whisper.

"Right away, General," the telegrapher replied, and with a pencil he wrote down on a telegram pad McClellan's dictation.

To Edwin M. Stanton Porter's Hd.Qtrs, June 25 11:40 p.m.

The information I receive on this side tends to confirm impression that Jackson will soon attack our right and rear. Every possible precaution is being taken. The task is difficult but this Army will do its best and will never disgrace the country. Nothing but overwhelming force can defeat us.

G.B. McClellan, Maj Genl

McClellan waited a moment, watching the telegrapher send the message over the wire. Then he returned to Porter's tent.

Fitz John Porter was waiting for McClellan. A lantern was hanging by a hook on the center tent pole when McClellan came in and, from its light, Porter saw there were dark hollows around his eyes and the drawn look of his face conveyed the impression of a man tense and greatly worried. He looked like he needed something to eat and a great deal of sleep. Inviting McClellan to come in, Porter took a step into the clearing and called for an orderly to bring a plate of food.

McClellan dropped into a chair by Porter's camp table. "Well, Fitz, it looks like you will be in a dog fight, maybe as soon as tomorrow," he said. He tried to get a tone of buoyancy in his voice, but his throat was dry from the heat and dust and instead it cracked.

Porter pulled a chair out from the table and sat down. For several moments he did not respond, wondering what to say. He went way back with McClellan. They had been classmates at the Point, had shared the hardships of campaign life in Mexico, and kept in close touch during the years McClellan was out of the army. He knew McClellan was usually a jovial, carefree character, full of pep. The mood he saw McClellan in now told him something very bad was about to happen, but he wasn't sure what.

He leaned forward and gave McClellan's arm a gentle tap.

"Mac, no need to worry, my corps can handle Jackson's," he said.

A wan smile momentarily broke the sagging lines of McClellan's face. "I have no doubt of it, if that's all you have to face."

A handsome, athletic-looking man, with dark eyes and a smartly trimmed beard, Porter projected an professional appearance of cool composure. McClellan was sure he would keep it in the excitement of battle. Heintzelman, Keyes, and Sumner, they were good for nothing but being Lincoln's stooges, but Fitz, Fitz could fight. He had the intelligence, the courage, the temperament that makes a fighter. In 47' Fitz's performance on the causeway leading to Mexico City's Belen Gate was testament to that. If any one can beat that devil, Jackson, Fitz can, McClellan thought.

McClellan sat in silence for a time while the lantern light threw flickering shadows across his face. He had been thinking for hours how to say it, but the words were sticking in his throat.

"Fitz, I'm afraid those monkeys in Washington have put us in a trap. I don't see any way out of it, but to retreat from here. And your corps must pay the butcher's bill for it."

Porter was startled by this, his body jerked a little as though reflexively avoiding something thrown. He shook his head in disbelief as McClellan's words sunk in. Retreat? The army was so close, the effort had been so great, and the army was strong, too strong to be overwhelmed, too strong to abandon the effort without a struggle. What did McClellan know that he didn't?

Porter leaned forward, opening his hands.

"Mac, we've been at this for months." He spoke softly, carefully, trying to reason it out. "How can we not fight? If it's Lincoln's holding McDowell back that's got you thinking this, now that Jackson's here he's got no good reason not to let McDowell go."

An angry look suddenly filled McClellan's face. His eyes seemed to redden with spite. He made a fist with his hand and slammed it down on the table with a thump.

"Fitz, the monkeys are rounding up McDowell's and Banks's and Fremont's troops into an army to be commanded by John Pope!"

Porter looked at McClellan, aghast.

"John Pope?" The idea was incredible. How could it be true?

"Yes, Pope, that's right, John Pope. Lincoln's calling his command, `The Army of Virginia.' Fifty, sixty thousand men. You know what that means? After our boys have died like dogs and we're bogged down, he'll send Pope to the rescue. I'll be the goat and Pope will be the hero."

Porter sat shock still, his hands clenched between his knees. It seemed fantastical. He remembered Pope from the Point, an upperclassman, brash, pompous, a name-dropper and glad-hander, who had spent his career in obscure outposts as a topographical engineer, marking trails on the Great Plains for the wagon trains. Last he had heard Pope was in Arkansas, just recently promoted to major general of volunteers. The thought struck Porter that he was senior to him on the commission list, as were all the major generals Pope would be commanding.

Porter looked beyond McClellan, off toward the dark forms of the pine trees at the end of the clearing. Why would Lincoln do this? It can't be he's still afraid the enemy will raid his captured territory. He knows that Jackson's here. It must be something else, but what?

Porter glanced at McClellan, he looked frustrated, distraught, angry. Could Mac be right, Lincoln wants the country to think the Republicans have captured Richmond, not the Democrats?

Porter thought of his contacts with Chase and Stanton, when he was in the Adjutant General's Office in the run up to the war. He knew Stanton as a two-faced vindictive man, capable of plotting against McClellan, and Chase as the mouthpiece for the Republicans. They don't want Mac to succeed, is that it? They fear the quick fall of Richmond will induce a push for peace which leaves the Negroes slaves and the South intact. They want battles and blood and causalities to trigger a change in the country first, so that a policy of freedom for the Negroes will be palatable. But not Lincoln, so far he's been trying to coax the South back by pushing the policy, the Union as it was. No, it must be something else.

Porter's thoughts were awhirl now; his mind in turmoil, perplexed. It doesn't make sense, he thought. Lincoln knows Mac can't achieve a decisive breakthrough of the Richmond defenses without the advantage of overwhelming force. For that, he knows Mac needs the troops he's giving Pope.

Porter sighed to himself as he considered this angle of things. Here, McClellan's idea came back to him. Lincoln wants us to bog down. Porter thought about this. Something about the idea just didn't fit. He remembered the things Lincoln had done to McClellan—selecting his corps commanders, stripping him of the authority of general-in-chief, setting up the department system, withholding troops—through it all, always prodding Mac to get bloody with the enemy.

Absorbed in these thoughts Porter finally felt comprehension strike. He leaned forward and touched McClellan's arm with his hand, giving him a look that seemed to say—Now I understand.

"Mac, it doesn't matter what his reasons are. Lincoln's commander-in-chief. He wants a bloodbath. Give him what he wants."

A flicker of annoyance crossed McClellan's face as Fitz said this. Fitz's words seared his mind like a hot poker. Of course, that's what Lincoln wants, Fitz, you got it right. He's playing the role of Commander-in-Chief, insisting that he pull the strings, manipulating me to do things his way. But I'm no puppet on a string. There's no way he's going to play me.

McClellan reached down to his saddlebag propped against his chair and removed a sheaf of paper, plopping it on the table.

"Here's Pinkerton's report I just received today. Bobby Lee's taken command of the field and he's got 200 regiments organized in 9 divisions, including Jackson's and Ewell's. Pinkerton estimates his strength at 180,000 men."

Porter picked up the papers and leafed through them. They were spread sheets, listing the rebel regiments Pinkerton's spies had found to be part of the rebel army. Next to the names of the regiments were the names of the colonels, the brigades the regiments belonged to, and the names of the division commanders.

Several minutes passed as Porter studied the columns of information. Finally, he set the papers down. It appeared Lee had a slight advantage in organization—although Mac had more divisions, Lee had more brigades and, thus, more regiments. But an important piece of information was missing.

"Look, Mac, Pinkerton provides no head count for the men in the ranks. We don't know whether the regiments are full, or half empty.

McClellan waved a hand dismissively. "Taking Pinkerton's estimate of 180,000, with his count of 200 regiments, gives each regiment 900 men," he said sharply.

Porter shook his head. "Pinkerton's estimate seems way too high. We have 153 regiments, counting McCall's. Our regiment strengths are closer to 700 men. Lee's are probably less. Remember Seven Pines, Mac, we handled the rebel attacks well enough."

"The odds are we will be contending against a force vastly superior to our's."

"You don't know that, Mac."

"I know we are too weak to advance against Richmond."

"But we have the numerical strength at least to hold our positions on both sides of the river, don't we? Once Lincoln sees us do this, he will know he can accomplish both his strategic goals simultaneously—capture Richmond and block raids into his territory—and he will order Pope to come down."

McClellan did not respond to this immediately. He looked away, rubbing his temple with a hand, his thoughts filled with malice toward Lincoln. If I have control of Pope's Army of Virginia, I can accomplish my objectives simultaneously, he thought—capture Richmond and hold my base. Damn that monkey in Washington, he expects Pope to operate at his instructions, not mine. Well, I'll be damned if I will allow it. Either I control all, or nothing at all.

He settled slowly in his chair and let his thoughts drift away, to his wife, Mary Ellen, and his infant daughter and his life before the war. He remembered his successes and his friends and wished he was running a railroad instead of being Lincoln's puppet. Shaking his head, like a man waking from a day dream, he shut the memory off and brought his mind around again to now. He would tell Fritz what he had decided on his ride.

"The people will rejoice when they see that I have saved the army from disaster by gaining a base that is secure."

So there we are, Porter thought. He's going to do it. Lincoln wants to see Mac engaged, holding his own with Lee, before he reinforces him with Pope's army, but Mac won't play Lincoln's game.

"At least let's wait until the pressure builds against my front," Porter said.

McClellan rose from the chair, and Porter, looking stunned, came to his feet too, his mouth working to speak. "Wait, Mac, listen to me - -"

McClellan cut him off.

"Enough, Fritz, enough. Lincoln isn't going to control me."

"Mac, he'll fire you."

"Well, let's see if he gets anywhere without me."

McClellan picked up his saddle bag and stuffed Pinkerton's report inside. Then he took hold of Porter's hand and shook it vigorously.

"Better send your heavy baggage over the river as soon as possible," he said. "As soon as Lee's attack develops, I mean to move the army to James River."

The two men's eyes met as Porter said, "All right, Mac, if that's what you want." Breaking their handshake, they walked together across the camp clearing to the picket line where Big Dan was standing. McClellan strapped the saddle bag in place and sprang to the saddle. Settling in the seat, he leaned down and put a hand on Porter's shoulder. "We can get along well enough without the help of that whelp, Pope."

Just as McClellan was turning Big Dan away, an orderly appeared carrying a steaming plate of food in his hands. Porter tried to persuade McClellan to stay, but he gave a quick salute and led Big Dan across the clearing and up the lane between the tents and was gone in the darkness. As he passed into the gloom of the trees, he thought of the words he had wired to Stanton and shrugged. The monkeys would get the message soon enough.

That same night

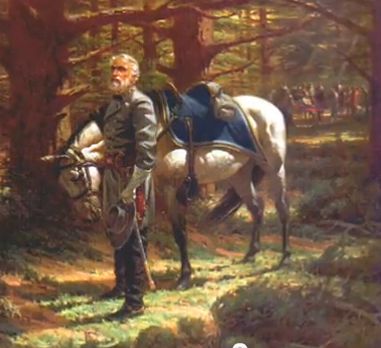

General Lee had ridden Traveller into the front yard of the Widow Dabb's house.

Charles Marshall and Walter Taylor, two of his staff officers, were standing on

the front porch as he came into the yard and they sent an orderly running

toward him. A small crowd of field officers and cavalrymen were in the hard

clay yard, and they all turned to watch General Lee ride in.

That same night

General Lee had ridden Traveller into the front yard of the Widow Dabb's house.

Charles Marshall and Walter Taylor, two of his staff officers, were standing on

the front porch as he came into the yard and they sent an orderly running

toward him. A small crowd of field officers and cavalrymen were in the hard

clay yard, and they all turned to watch General Lee ride in.

He nodded at several of the ranking officers and returned a salute tendered by a cavalryman who was standing close by. Leading Traveller along a row of horses picketed at the fence, he turned him into an open slot. Dismounting, he raised the flap of his fan saddle and released the girth and breastplate straps. Lifting the saddle off Traveller's back, he set it down on the rail of the fence. Then he took off Traveller's bridle and replaced it a rope halter

and handed the rope end to an orderly. "Can you get him some fresh hay and oats and brush him down?" He said as he ran his hand through Traveller's black mane.

Taking hold of the halter, the orderly began backing Traveller away from the fence as General Lee stepped out into the yard and headed for the house. "Yes sir, Gen'ral, I reckon I can," the proud orderly called after him.

When General Lee stepped onto the porch, Walter Taylor came close to his side and quietly addressed him: "Mrs. Lee's servant boy came by two hours ago to say that she hopes you might visit her in Richmond tonight."

General Lee stopped and nodded at Taylor. Taking off his Stetson, he swept a wisp of salty black hair back from his temples. His eyes seemed to sink under his brow in the gathering darkness, reflective and distant. He had not seen his wife, Mary, since she had been escorted to the river by a squad of McClellan's cavalrymen, three weeks earlier. She had ridden over the Meadow Bridge in the seat of a ramshackle spring wagon, pulled by an old mule and emaciated horse and driven by the servant boy. Sitting behind her, on a leather coach trunk in the bed of the wagon, were two of her daughters, Mildred and Agnes. When the wagon clattered over the bridge and came into the rebel lines, General Lee rode Traveller alongside and his wife leaned down and handed him a tomato. They spoke briefly together, the wagon rocking and swaying in the deep ruts of the road, before he turned Traveller back toward the river.

With Marshall and Taylor following him, General Lee opened the front door of Widow Dabb's house and passed down a corridor between the parlor and dining room—two long rooms with fire places and low ceilings—and went into a small back room that served as a kitchen. When he entered the kitchen, his colored servant, Jerome, was standing over a wood-burning range with a fork in his hand, frying slices of potatoes and onions in bacon grease in a pan. Jerome wore the uniform of a house servant, white shirt and black wool pants under a striped cotton coat. He was one of the Danridge negroes that came to Mrs. Lee with her inheritance of Martha Washington's old plantation on the Pampunkey. The Negro was taller than General Lee, and thinner: his head shaved bald, his eyes shining like black china marbles, his skin a deep lustrous black, the purity of his ancestry from a fierce cannibal people was glaringly evident.

Turning at the sound of foot falls behind him, Jerome saw General Lee's dust-caked face and frowned. He pointed with the fork at a steaming iron tea kettle sitting at the back of the range. "Better git washed up, Mister Robert, be'fo I burn your tators," he said with an exaggerated inflection.

General Lee came to the range and looked at the food sizzling in the pan as Jerome thrust a piece of cloth in his hand. The potatoes and onions were almost ready to eat, glazed golden brown by the drippings. "The potatoes look grand," he said. "I'll just be a minute or two." He gripped the wire handle of the kettle with the cloth and carried it into the corridor, where he went quickly out the back of the house to the rear veranda. A cook out of temper can spoil a dish just by the turn of a hand and General Lee was too hungry to take chances.

A wash basin sat on a shelf against the exterior wall. He went and poured the kettle's contents into it. Setting the kettle down, he took off his mud-spattered gray coat and hung it on a peg in the wall. Rolling up the sleeves of his shirt, he picked up a bar of gritty brown soap, and, lathering his hands, he scrubbed the trail dust from his face. Pretending to ignore him, a speckled, black hen sat motionless in a nest of hay perched on the opposite end of the shelf. Chuckling to himself, General Lee wiped himself dry and pitched the water in the basin over the edge of the veranda. Then he took down his coat from the peg, and, giving the hen an appraising glance, he reentered the kitchen.

A small table flanked by two ladder-back chairs sat in the middle of the room. The table was covered with a red-checkered table cloth and a place was set with a tumbler glass, a big silver knife and fork, and a napkin. In the center of the table a candle was burning in a brass holder. Hanging his coat on the back of the chair, he sat down and watched as Jerome opened a small door in the side of the range and removed a strip of beef steak with a pair of tongs and laid it on a warm china plate. Scooping the fried potatoes and onions from the pan with a spoon, the Negro lathered them on top of the steak and carried the plate to the table and set it down in front of General Lee.

Just as General Lee began cutting into the meat, the sounds of thudding boots and the clank of a sword dragging on the corridor's plank floor carried into the kitchen.

Hearing the commotion in the corridor, Charles Marshall, who was in the parlor with Taylor, stepped into the corridor and intercepted a rough-looking cavalryman who had tramped into the house. After a brief conversation, the cavalryman handed Marshall a folded piece of paper and turned away. Pushing his chair back from the table, Lee took the paper from Marshall and read it. When he finished, he signed to Taylor, who had followed Marshall into the room, to take it. Then he turned back to the table and, as he cut into his steak again, said to Taylor: "Please send a courier to A.P. Hill's headquarters. Tell him I wish Branch's brigade to march at first light across the river, the rest of the division to stand ready to move across at my order."

Walter Taylor took the paper from General Lee and, reading it as he exited the kitchen, he went across the corridor into a carpeted room behind the parlor. A field desk was set up in front of a wide west window. Several cane chairs and a couple of three legged stools were scattered around the room. An embroidered blue and white quilt covered a narrow bed made of chestnut wood in one of the corners. An old mahogany desk was in the corner opposite. When Taylor came in the room, a subordinate staff officer, Captain Mason, was sitting at the field desk, sifting through a stack of ledgers and letterbooks. Taylor reached over Mason's shoulder and selected a letterbook and sat down next to the desk.

As Lee's adjutant, Taylor's primary duty was to supervise the writing and transmission of the army's movement orders. Opening the letter book, he turned to a blank page and wrote down, in pencil, the date and time in the right-hand corner of the page, then the addressee, and finally he wrote down General Lee's message. When he was done he handed the letterbook to Mason and told him to copy the message and send it by courier to the headquarters of General A.P. Hill.

By the time Captain Mason made the copy and had gone to find a courier to carry the message to Hill, General Lee had finished his supper and was standing at the side of the table, making way for Jerome to clear the plates and utensils. Rolling down his sleeves, he buttoned his cuffs and took his coat in his hand and headed toward the kitchen door. Stopping at the threshold, he turned, and, with a warm quality in his voice familiar only to those who were members of his family, he addressed the Negro: "If that hen of your's lays any eggs by morning, will you poach them for me?"

Jerome's jet face crinkled with deep criss-crossing grooves that glistened in the flickering light. His huge nose flared and his mouth spread wide, showing a set of ragged white teeth, and his eyes brightened with something like affection. He could have run with the others when the Lincoln soldiers came to the Pampunkey. He had the intelligence and skills to take care of himself in the free world he knew was coming at last. But he knew, too, that he still would have to serve somebody, and he knew no one better to serve at the moment than General Lee.

He gave a throaty mocking laugh. "Now you know Gin'ril, dat ole hen can't lay no eggs with dem Linkum battery guns busting an' roaring all day."

Walking out of the room as Jerome spoke, General Lee stopped for a moment to reply: "Well then, you might as well roast her up for dinner tomorrow night."

"The time for dat will come soon nuff," Jerome shot back—"when you git down to nuttin' left to eat but biscuits and beans."

Leaving the kitchen, General Lee crossed the corridor and went into the back room behind the parlor. Except for Walter Taylor, who was busy organizing papers at the field desk, the room was empty. Lee stepped past him and went to the mahogany desk that filled the far corner of the room. He took a seat in a leather swivel chair in front of it and penned a note to his wife, Mary.

June 25, 1862

My Dear Mary:

I have been on our lines all day, and having finished my supper find it near 10 p.m. with a great deal to do tonight. I expect we will have a fight tomorrow. It is therefore impossible for me to see you. I pray we may have happy days yet.

Very truly and affectively, R.E. Lee

Folding the note, he inserted it into an envelope and sealed it, writing "Mrs. Mary Lee" on the outside of the envelope. He got up and handed it to Taylor. "Ask Jerome to please take this in to Richmond tonight," he said. "Tell him to stay there with Mrs. Lee until I send for him."

When Taylor had left the room, General Lee opened a set of sliding doors and stepped into the parlor. The room had the air of being well lived in. A sofa with a carved mahogany frame stood in front of a fireplace, flanked by two fat horsehair chairs. Next to the sofa a burning oil lamp sat on a marble-topped table, casting the room in a circle of merry glow. A green carpet covered the floor. Canvas paintings crowded one wall between two wide windows. A grandfather clock stood in a corner. Here, in the long months of winter, when the snow was falling over the house, Widow Dabb would sit in front of the warm hearth and read. In the summertime, when the twilight spread across the forest, she would sit in the window seat and watch the light of the sinking sun burn on the evergreen trees. Remembering his Arlington home for a moment, Lee saw the room as a pleasant place to be.

Charles Marshall was sitting in one of the horsehair chairs when General Lee entered the parlor. Sitting on the sofa was a young man dressed in civilian clothes named Seaton Tinsley. Tinsley's family lived on a farm on the left bank of the Chickahominy, behind Doctor Gaines's big, double-winged mill pond. When McClellan came up the Peninsula, Tinsley had gone into Richmond and taken a position as a clerk in the office of Judah Benjamin, the Confederate Secretary of the Treasury. Rising from his chair, Marshall introduced Tinsley to General Lee as he gave the young man a beaming smile.

"Marshall tells me that you know the roads on the other side of the river like the back of your hand," General Lee said.

"Yes sir, I do," Tinsley answered.

"Well then, I want you to look over a map our engineers have made, and tell us if it correctly shows the roads."

Gesturing for Tinsley to follow him, General Lee walked across the corridor into the dining room, where a large piece of canvas was spread open on the dining table. A burning candelabra hung from the ceiling, throwing a yellow cone of light on the table. Tinsley bent over the table and examined the details of the map as Lee began peppering him with questions.

Widow Dabb's grandfather clock was stroking the two o'clock hour when General Lee returned to the room behind the parlor. Striking a match, he crossed the floor and lit an oil lamp on the mahogany desk where he had written his note to Mary. Then he sat down and penned a message to his President.

Jefferson Davis June 26, 1862

Sir:

A note just received from General Jackson states that in consequence of the high water and mud, his command only reached Ashland last night. The enemy has been moving on our extreme left beyond the Chickahominy. Our cavalry pickets were driven in that direction and the telegraph wire near Ashland is cut. Tomorrow I will be on the Mechanicsville road.

I am most respectfully, your obedient servant

R.E. Lee, Genl.

Rising from the desk, General Lee stepped into the corridor and went to the door of the dining room where Marshall was busy tracing revisions that Tinsley had made on the canvas map. He held out his letter to Davis as Marshall came to the door. "Give this to Taylor, tell him to send the original by courier to Richmond at first light."

As Marshall hurried away, Lee walked to the back of the house and went out to the rear veranda. Stepping along the railing he listened to the sounds of the night, the muffled "yip, yip" of a solitary dog running down something in the woods, the distant hoot of an owl, leaves tinkling in a faint breeze, the groggy humming of the insects in the trees. Coming to the end of the veranda, he stopped in front of the nest of Jerome's speckled hen and gently slipped a searching hand under the belly of the bird as it clucked nervously at the intrusion. Finding no eggs, he stepped away from the nest, with the flicker of a bemused smile on his face, and stood at the veranda railing, looking up at the black vault of night sky, glittering with diamond and sapphire stars.

High in the dome of the sky, the big dipper hung by its handle, with the two stars marking the front of the bowl guiding General Lee's eyes across the void to Polaris, in equipoise over the pole. Standing on end over the pole star, like a circus clown balanced on a ball, the little dipper seemed to be swinging its cup to snare the underbelly of Draco, the coiling dragon mythically gliding in the sky. A frown darkened General Lee's face as, suddenly, the sight of Draco in flight was carrying him back in time to the Texas plains, and the long June nights he spent at Camp Cooper in the valley of the Clear Fork. He was in Ketumsee's tent again, squatting on the earthen floor next to the smoking cook fire, feeling the pride of the conqueror, impervious to the pathetic plight of the Comanche chieftain's tribe. Now he was surprised to realize a vague feeling of kinship with the red man and he wondered why.

Suddenly, a meteor flashed through the stratosphere and disappeared—a pencil-thin streak of brilliant white light in the sky stabbing at Draco's heart. And General Lee knew. It had taken the Union decades to occupy the heartland of the Comanches and crush their resistance to Union rule. It had taken the Union but twelve months to position itself to occupy the heartland of the Confederacy and now the Union power was on the verge of administering the coup de grace. With the dark face of Ketumsee sharply etched in his mind, he knew in his soul his people's fate was as the Comanches in the end. With no more chance against the power of the Union than the Comanches had, his people would fight for their land to the bitter end. A great breath slipped slowly from his barrel chest as he thought this, because it came to him then that, like Ketumsee, there was nothing to be done but take the young men of his tribe forward as best he could to their end.

In midafternoon, the next day, General Lee rode Traveller into Longstreet's headquarters camp as the booming sound of a single gun reverberated among the bowering sycamores that fringed the Chickahominy's bottomland. At the walk, Traveller carried General Lee forward into the midst of the tents and stopped in front of a group of men lounging in the shade of a sweet smelling magnolia tree.

James Longstreet sat in a chair with his boots propped against the tree trunk, engaged in laughing conversation with those about him. He was a big, beefy man of German descent, with a sandy beard and moustache and thick black hair set far back on his temples. He had piercing blue eyes and a solid nose laced with tiny red veins that suggested he was capable of heavy drinking. The son of a small-time planter, he had entered West Point, in 1838, where he excelled at horsemanship and little else. Graduating in 1842, he served in infantry regiments in the west, eventually becoming a paymaster, until he resigned, in June 1861, and traveled to Richmond where he obtained a commission as a brigadier general.

There had been winners and losers among Joe Johnston's division commanders when General Lee took command of the army. Longstreet seemed for the moment to be one of the losers. When Johnston was in command, Longstreet had exercised command of the army's rear guard at Williamsburg and its right wing during the battle of Seven Pines. Now, except for Whiting, who General Lee had sent away from Richmond with half the size of his original division, Longstreet commanded the smallest division in the army. The clear winner in the transition was Jackson, whose command had increased from one division to three. Another winner was A.P. Hill, who received promotion to major-general rank and now commanded the Army's largest division of 14,000 men. Stubborn in the idea his way of strategic thinking was always right, Longstreet would soon prove himself to be a capital soldier in managing the operations of a corps. Of all General Lee's original division commanders, only James Longstreet would reach the field at Appomattox: the night before the surrender, lying on blankets twenty-five yards apart, he and Lee waited for the army's last dawn together.

"A.P. Hill is moving now," General Lee said as he reined up. "When D.H. Hill gets his division over the river, start your division for the New Bridge and follow him across."

Traveller stood still as General Lee spoke to Longstreet, his ears pricked forward, black nose thrust out, his nostrils flaring. Then he felt his master's legs touch his flanks, and he whirled and was off along the tree line taking long strides.

Watching General Lee ride off, Longstreet shook his head in disapproval: General Lee was massing 21 brigades of his army—over 56,000 men—on the left bank of the river to attack the 9 brigades of Fitz John Porter's corps. This left only 13 brigades on the right bank to stand against 24 of McClellan's. To gain a 2 to 1 superiority against the enemy on the left bank, Lee was leaving his army outnumbered 2 to 1 on the right bank. It's reckless, too aggressive, Longstreet thought.

Riding south a short distance, General Lee brought Traveller to the trot and then a fast, heaving walk, leading him into the throat of a ravine that cuts the Chickahominy bluffs and down the long grade to the bottomland. By the time he came out of the woods into the bottomlands, he heard the cracks and thuds of flying artillery shells echoing from across the river and he knew A.P. Hill's brigades were driving the enemy skirmishers through the tiny village of Mechanicsville.

A series of mushy tracks, laced with boardwalks, had been built across the marshes on the right side of the river, leading toward the bridgehead at the crossing of the main channel. Long lines of D.H. Hill's soldiers were on the tracks, crowding up to the channel on either side of the bridgehead. Toward the point where the New Bridge Road met the bridgehead at the channel, the ranks of men were stepping off into the marsh and wading across the channel in the muck. In the middle of the roadway, teams of horses, in an artillery train, were standing still in a long file.

Leading Traveller along the edge of the road, General Lee came up to the bridgehead and found a company of pioneers working up to their waists in the black water, reconstructing the burnt sections of bridging that had spanned the main channel of the river. The pioneers had beams in place over the pilings and were laying down planking to make a deck for the bridge. As Lee watched the pioneers work, Jefferson Davis, followed by a band of clattering, dusty horsemen dressed in civilian clothes, came out of the forest and posted down the road, passing the infantry and the artillery carriages with their limbers and caissons. Reaching the bridgehead, Davis sidled his horse to a stop next to Lee's.

Behind Davis, the cavalcade of civilians reined their mounts to a stop in the narrow space between the artillery train and the shoulder of the road, their horses, bumping and jouncing and snorting in the sudden confusion. As the throng of riders got their mounts under control and the dust was settling, General Lee looked coldly at the President, and, jerking his head toward the crowd of riders, he said in an incredulous tone, "Who are all this army of people, and what are they doing here?"

A flush of color appeared on Davis's face. No one within ear shot moved or spoke, but all eyes were upon Davis. He twisted angrily in his saddle and looked upon the crowd of horsemen: There were several Confederate congressmen, a few newspapermen, and several of his personal aides, including James Chestnut, ex-U.S. Senator from South Carolina, and Benjamin Harrison, his military secretary. From beyond the river bluffs, the roar of artillery and rattling rifle fire swelled and faded and rose again. Off the sides of the road, the young brown soldiers wading across the river shot glances at them and the cannoneers on their limber boxes, and the drivers on their lead horses, watched with rapt attention.

Davis gripped the pommel of his saddle and turned round to face General Lee. "It is not my army, General," he snapped.

"It certainly is not my army, Mr. President," General Lee said with a mocking smile, "and there certainly is no place for it here." For a long moment no one spoke or moved. Then, slowly, one by one, the riders turned their mounts around and began to walk them away. Returning to the hard ground where the road turns upward, several of the horsemen slipped off the road into the timber, to wait their chance to follow the army across the river.

By this time the pioneers had managed to get in place one long strip of rickety planking across the beams, and General Lee, touching Davis's arm, nodded toward the bridge. "Follow me across," he said, as Traveller clopped onto the planking.

George McClellan was standing with Fitz John Porter on the ridge above Beaver Dam Creek, when D.H. Hill's soldiers came howling through the clover fields of Dr. Catlin's farm and ran down into the creek valley, as Porter's artillery batteries, firing canister, some at point blank range, ripped their ranks to shreds. By the time the survivors of the charge had reached the creek bed, a thousand dead and wounded men laid in scattered heaps over the ground.

Watching his men get slaughtered, D.H. Hill spurred his horse back and forth along the ridge of the valley, shouting orders for his artillery to get into action. But, by the time the first lanyard was pulled, the valley of Beaver Dam Creek was a pit of groaning darkness and D.H. Hill was furious at General Lee. Slender in frame, with a face covered with a short black beard, Hill had bright blue eyes and they radiated his anger now.

As the rays of sun were throwing long shadows across the fields, a courier had come to him with an order from General Lee to attack Porter's left which had been assailed by several rebel brigades with no success. Hill had ridden directly to General Lee, finding him with Jefferson Davis on the rise of a small hill. Riding up, he saw several of A.P. Hill's brigades standing idle in a field. Reining his horse in front of Lee, he had jerked his head toward these idle brigades and said, "Why are you calling on me when those men are standing right there?"

General Lee looked at Hill and said nothing. He had ordered A.P. Hill to position the brigades where they stood, and he had no intention of moving them away. Most of D.H. Hill's division was jammed up in the river bottom. Longstreet's division was still holding its position on the right bank of the river, and, to the northeast, at a place called Pole Green Church, the three divisions under Jackson's command were not yet assembled in battle formation. Though the sun was falling fast, the enemy still had plenty of time to launch a counterattack and A.P. Hill's brigades were General Lee's only reserve.

D.H. Hill's face reddened and he squinted at General Lee. "It's suicide to charge the enemy with only one brigade. Let me wait for the rest of my division to come up."

Lee's face was expressionless, his eyes fixed on Hill. He knew Hill was right, of course, but, he wanted the pressure kept up. "You must send in the men you have immediately," he said.

D.H. Hill wiped a hand across his bearded chin and pulled his horse roughly around and brought it to stand next to President Davis. "My men will be murdered if they go in there alone," he said. "Can we not wait until tomorrow when Longstreet and Jackson will be up?"

Davis wagged an open hand at Hill, signaling him to stop. "This army is under General Lee's command, sir, not mine," he said.

Shaking his head in disbelief, Hill looked from Lee to Davis, his mouth open but no words coming out. Then, slapping the flank of his horse, he had galloped along the ridge of Dr. Catlin's farm and, coming upon Pender's brigade at the river bluffs, he had ordered the men into the carnage.

When night finally fell, and the rebel infantry charges were petering out, George McClellan rode with Porter to Porter's headquarters. For the first mile, they rode together in silence, each man thinking on what he expected would happen on the morrow. When they came onto the Gaines Mill Road, under a canopy of emerging starlight, Porter broke the silence with an emphatic slap of his hand against his thigh. Excited by the battle action, he was full of himself with pride and confidence. "My God, George, I know secesh means to throw their masses against my flanks tomorrow, but if you bring two additional divisions over here tonight, we have a good chance of whipping them badly."

Without answering, McClellan put Big Dan to the trot and posted down the wagon road, leaving Porter behind to hustle his horse to catch up. As he rode, he thought about what he had seen, the reports he had received. According to Stoneman's scouts, Lee now outnumbered him two to one on the right bank of the river. This was good news. It meant the force Lee had left on the right bank was too weak to prevent him from moving the army south through White Oak Swamp to James River. Satisfied he had calculated right, McClellan abruptly tugged on the reins, stopping Big Dan in the road to stand as Porter brought his mount alongside.

The two horsemen sat silent in the saddle for a time, looking up at the two bears tumbling round the pole star in the sparkling darkness. Above the bears, they saw the slithering body of Draco stretched across the vault of sky. Finally, McClellan turned to Porter and said, "Fitz, we've got Lee now where we want him. He's too weak on the right bank of the river to stop us from moving the army to James River, and, with the advantage of the defense, your corps has the strength to fight him to a standstill over here."

As he listened to McClellan speak, Porter shifted uneasily in his seat and his gaze drifted from the stars to the murky darkness surrounding of the road. When McClellan had finished, he slowly shook his head. "But George, what will they say if we retreat without a fight?" he said.

McClellan led Big Dan a step closer to his friend's side and placed a hand on his shoulder. "Fitz, I could reinforce you enough to make it a straight up fight with Lee for our base, and probably hold it, but then I lose the opportunity to move to James River. I won't do that."

Fitz lowered his rein hand to the pommel of his saddle and looked into the gloom, his thoughts considering the angles of the situation: Yes, even if Mac reduces his force on the right bank, by half, he would only be making the match up with Lee on the left bank even. To have any chance of overpowering Lee's force Mac has to have overwhelming strength at the point of attack—and that can only come from Lincoln's new paper army under Pope.

Mac was right. The army would get bogged down if it stayed on the Chickahominy now, and the country would see Pope as the great man of the hour. Fitz felt bile rise in his throat at the thought of being rescued by Pope.

He turned to McClellan. "All right, Mac, I'm with you, but you must be ready to reinforce me when the going gets tough."

"Come on, then," McClellan said, kicking Big Dan into a canter as Porter put the spurs to his horse simultaneously.

A mile down the road they came to a bend and saw flickers of lantern light in the near distance. Slowing to a trot, they continued on until they came to a checkpoint manned by pickets. Passing the pickets they came upon another checkpoint and then yet another, until, finally, they reached the fields where Porter's reserve—Morell's and Sykes's divisions—had been encamped the night before. Continuing beyond the deserted campgrounds, they crossed over the trestle bridge by Gaines Mill, and went round the bend of Dr. Gaines's farm field and led their horses on to the farm lane that goes down to the Stewart farm house and passes Boatswain Creek.

On the west side of the creek, they climbed a rise and came out on a broad plateau, gleaming silver under the star light of the night. Here the farm lane forked, the left crossing the plateau in the direction of the Grapevine Bridge, the right going past the Watts family's farmhouse and dropping down a mile's distance behind it into the Chickahominy bottomland.

Reaching the Watt's abandoned house, McClellan abruptly wheeled Big Dan around and extended his hand to Porter. "Tomorrow I will start Keyes's corps across White Oak Swamp. Once we have secured the opposite side of the swamp, the wagons and artillery of the army will follow. I want you to take your position here. Hold the enemy back until the movement to the James is commenced, then bring your corps across the Grapevine Bridge."

Fitz leaned forward in the darkness and gripped Mac's hand in his own. He looked into his old friend's eyes. "I will do it, but you must reinforce my corps."

Mac nodded. "I will send you Slocum's division in the morning."

Then, breaking off the handshake, he kicked Big Dan into a loping gait and went quickly away into the night.

Fitz John Porter remained where he was for a time, looking around the plateau, noting the location of the Watt farmhouse, the orchard behind it, the flat fields stretching away toward the west, the woods covering the slopes of the narrow little valley Beaver Dam Creek runs through. Well, Mac, he thought as he turned his mount and began riding back toward Gaines Mill, I'll do my best to hold this place but I'm sure going to need Solcum.

VII

The guns Fitz John Porter left in battery behind Beaver Dam Creek began to boom as soon as the Richmond sky blushed in the morning. Behind the guns that answered them, the men of A.P. Hill's brigades laid on the damp ground along the edge of the Mechanicsville Pike, listening for the sound of the bugle that would send them forward into the fields where the enemy's shells were falling. Across the Chickahominy, the men of Longstreet's division streamed out of the trees on to the bottomland and waded the channels. And D.H. Hill's division, now joined with Jackson's command at Pole Green Church, began to advance.

Two hours later, with the sky over Beaver Dam Creek criss-crossed with hundreds of white vapor trails, the sound of the Union guns began to lessen, their fire becoming sporadic and more distant, until, finally, it died out completely. In the silence that followed, the ta ta of a bugle sounded and thousands of men in tattered homespun tread forward in skirmish formation past the graying faces of the dead, strewn down the broad slope of Dr. Catlin's farm. On the far right of the battle line, the lead regiment of A.P. Hill's men passed over the little foot bridge at Ellerson's Mill and found the Union rifle pits abandoned. Moving over the hill and into the trees, the rebel skirmishers went steadily on as the rest of their fellows splashed over the creek and followed them. A mile to the right of Hill's line of march, the head of Longstreet's division came up to the crest of the Chickahominy bluffs and turned down the bank, following the network of tracks that snake through the woodland toward the swamp ground of Powhite Creek. Two miles to the left of Hill's line of march, the divisions of Jackson's command, one behind the other, marched in the direction of Bethesda Church.

At the center of the rebel advance, A.P. Hill's skirmishers—men from Gregg's South Carolina Brigade—came to the edge of the brown fields in front of Gaines Mill. The fields were shimmering with heat waves from the rays of the morning sun and columns of black smoke curled upward from the piles of burning rubbish and discarded supplies of the retreating Union army that dotted the landscape. Spreading out into the fields, the skirmishers walked toward Powhite Creek and Dr. Gaines's wing-shaped mill pond. Next to the mill dam a wagon bridge, carrying the road to Cold Harbor over the creek, was ablaze and beyond it a company of Union soldiers could be seen.

A half-mile from the bridge, rebel field officers rode back and forth along the ranks of the lead regiment of Gregg's brigade. Shouting orders, they led their men into the fields in front of the creek while the long column stretching back toward Beaver Dam Creek came to a halt on the road behind them. Thousands of glittering points of sunlight flashed back to the horizon as the South Carolinians shuffled to a stop in the road and swung their rifles off their shoulders, the butts in unison dropping to the ground with a great clattering noise. At intervals along the glimmering line, the color guards of the regiments unfurled their palmetto ensigns and star-crossed crimson banners and let them flap and curl lazily in the sultry breeze. Then a trumpet sounded, and the skirmish line opened fire on the enemy on the other side of the creek.

When the Union soldiers saw the rebel skirmishers coming on, they tossed aside the kerosene cans they had been using to fire the bridging and began to run; retreating along the edge of the mill pond, they disappeared into a clump of pine trees on the fringe of its upper reaches just as the South Carolinians reached the creek bank. Waved forward from the rear of the rebel brigade, a gang of bronze pioneers, naked to the waist, came running up to the bridge with canvas tarp and quickly whipped the flames into submission. An hour later the bridge span was repaired and the five regiments of the South Carolina Brigade began to cross over the creek.

Suddenly, the fifty or so Union men who had taken refuge in the pine thicket, broke from their cover and fled west across the field. As they went dashing away, a few hundred men from the front rank of the forming rebel battle line stepped into the field and discharged their rifles at the running targets. In the fusillade many of the Union men were shot and fell down between the green-fleeced furrows of the field. The rest of them were able to scramble clear of the field and, running helter-skelter down the Cold Harbor Road, they disappeared into a thick belt of woods that skirts the Stewart farm lane in front of Boatswain Creek.

As the sound of the rebel rifle fire was falling away, a lone figure in blue raised up from the furrowed ground and staggered several steps in the direction of the Cold Harbor Road. Seeing the Union soldier was wounded and alone in the field, someone among the rebel soldiers cried out, "Surrender, you dammed Yankee." The distant figure in the field kept moving forward for a moment. Then, he stopped and faced about as the rebel soldiers were turning sideways again and leaning backwards; their crooked elbows nested against their hard ribs, they lifted the long barrels of their rifles in the cradles of their hands and pulled back the hammers with their thumbs. Realizing that he was at the edge of death, the hapless fellow pulled himself erect and glared defiantly across the field at the brown faces sighting at him down the barrels of their long rifles. "Damn you rebel traitors, I will not," he hollered across the furrows.

A hush descended on the crowd of riflemen, each man frozen for a moment in the attitude in which he was caught when the Union soldier's curse reached his ears. All of these neophyte man killers, to whom the horror of war was fast becoming a familiar thing, sucked in their breath as amazement registered on their grim faces. Then the spell was broken and, their shrill voices choking as his did with emotion, they screamed hoarse cries of "Shoot him," Kill him," "Down with the billie boy." And with that, a salvo of crackling rifle fire ripped along the front rank of the South Carolina Brigade, and the blue clad figure in the field lurched, then staggered and stumbled as the tiny leaden spheres of death whistled by his flaying arms and bobbing head until someone's aim slammed a bullet into his brain.

Before the dead man's body hit the ground, the drums and trumpets from a rebel regimental band across Powhite Creek began to play a new tune that the rebel soldiers had heard the enemy singing in their camps behind the Highland Springs ravine. Taking up the lyrics of the refrain, the men of the South Carolina Brigade began to chant in deep rancorous cadences as they advanced in mass across the field, "We are coming, Father Abraham, the Union to resolve. We are coming, we are coming, Father Abraham, three hundred thousand strong."

Standing with his staff officers on the knoll where the Watt house sits behind Boatswain Creek, Fitz John Porter heard the song, its echo broken by the distance and the trees. Well, here they come, he thought. Stepping forward, he grabbed the sleeve of a cavalryman seated on his horse nearby and yelled into his ear—Ride to Dr. Trent's farm and inform General McClellan that we are engaged with the enemy. Tell him I call for Slocum." Nodding his head, the trooper kicked his mount into motion and went galloping across the plain toward the Grapevine Bridge.

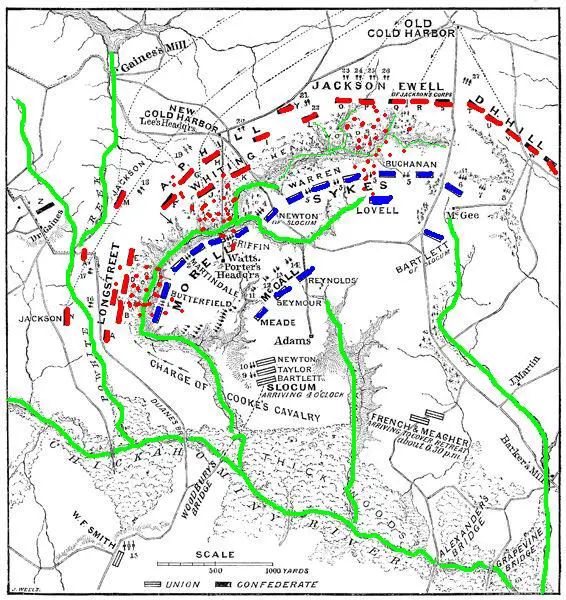

Five of Porter's nine brigades were in position along a curving two mile front, from the nose of the plateau where Boatswain Creek falls into the swampy Chickahominy bottomland, to the farm fields where the creek's tributary streamlets rise in front of the Cold Harbor crossroads. The rest were in reserve. The first line was near the bottom of the slope that meets the creek, behind a row of felled trees held in place by sharpened stakes. The second was at the mid-point of the slope behind a similar barricade. The men of the third line were hunkering in rifle pits at the edge of the plateau.

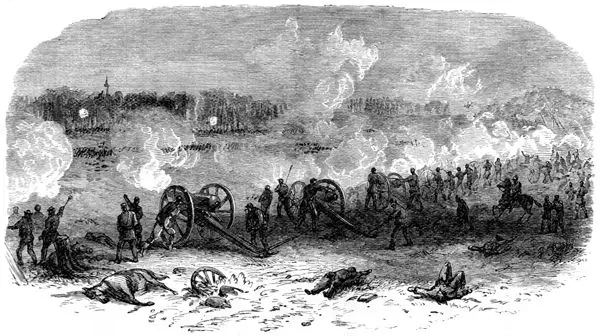

An array of cannon supported the Union infantry from different sectors of the field. In the middle ground of the plateau, three sections of rifled field pieces were in position behind earthen mounds spread in a semi-circle several hundred yards apart, their muzzles pointing toward the open fields in front of Gaines Mills and the belt of woodland that blocked the Stewart farm road from Porter's view. Toward Porter's right, the grade of the slope from the creek bottom to the plateau flattened out toward the junction point of the two branches of the creek, which were shrouded by woodland. In this flattened space, behind the Union infantry lines, six Napoleon field pieces were positioned in an arc, the center of which was in front of a bridle path that crosses the main channel of the creek near the point where the streamlets meet. Where the Stewart farm road enters the waist of the plateau, there were positioned twelve more cannon. Twenty-four guns in all, with another ten in reserve.

To the men of Porter's corps the sweltering sun seemed suspended in its movement as they strained to decipher the flux of sound carried with the echos of the rebels' song. Off to the east, they heard the trampling hum of a large mass of infantry moving into the fields in front of Beulah Church. Closer still, they heard the shuffling tramp of thousands of feet in the fields in front of Boatswain Creek. Mingling with the tramp of feet, were the clattering sounds of metal cups and canteens slapping against legs in marching rhythm, the creaking and rattling of wagons and artillery carriages moving along the farm lanes that criss-crossed the countryside.

From his station at the Watt House, Fitz John Porter glassed the gaps in the tree line covering Boatswain Creek and caught glimpses of rebel soldiers at the edge of the opposite ridge of the creek valley. He could see teams of horses galloping forward through gaps in the lines of the rebel troops, dragging forward limbers, field pieces, and caissons. "Tell the cannoneers to start firing," he yelled to a mounted courier who instantly raced away across the plateau toward the Union battery emplacements.

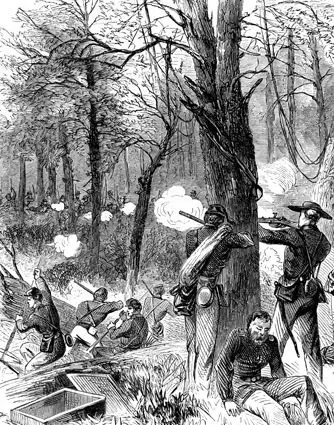

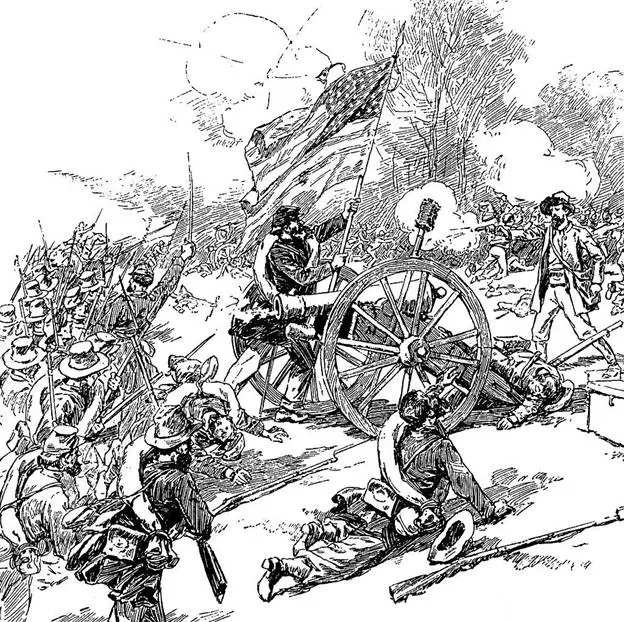

Moments later the concussive sound of an explosion was rushing toward the advancing rebels like the drone of a distant train, rising to a roar with a horrible velocity across the intervening space. Out in the fields, the rebel skirmishers, their eyes gleaming above their clenched teeth, bounded forward with wild yells into the trees as Porter's first shell rained hot fragments of iron on them. Behind them three ragged lines of soldiers, made up of A.P. Hill's six brigades, came on like rampaging waves, sweeping into the south sector of woods that covered the swampy ground behind the Stewart farmhouse. The men in the first wave rushed through a wide belt of woods, splashed into the shallow creek water and threw themselves against the opposite bank. With curses and cries of "send em to hell boys," the defending Union infantry rose up behind felled trees and withering blasts of rifle fire swept back and forth in the forest.

With

a throbbing, thunderous roar of rifle and artillery fire enveloping them, two

solid walls of men collided in the interspaces between the trees. Keen hissing

sounds filled the air, ending with a whine and a thump and a thud as thousands

of ounces of hot lead smashed through the tree branches, rotating and

ricocheting their trajectories in flight, to spend their energy whirring away

harmlessly, or punching a terrible hole in someone's flesh. Amidst the rattle

of  rifle fire and the thunder clap

of cannon, men in dirty homespun woolens came rushing with the bayonet. The

struggle became now a scene from hell: the woods filled with the stench of sulphur,

given off from the black powder bursts of thousands of rifles. Screams and

groans of agony issued from the throats of dying men as bayonets were plunged

into the stomachs and rifle butts smashed skulls open—the sheer terror of it

all shocking the defenders and energizing the attackers into a frenzy as they

trampled over dead and wounded bodies, wedged a lane through the crush of

struggling bodies and reached the edge of the cornfields that spread away to

the west in front of the McGeehee house.

rifle fire and the thunder clap

of cannon, men in dirty homespun woolens came rushing with the bayonet. The

struggle became now a scene from hell: the woods filled with the stench of sulphur,

given off from the black powder bursts of thousands of rifles. Screams and

groans of agony issued from the throats of dying men as bayonets were plunged

into the stomachs and rifle butts smashed skulls open—the sheer terror of it

all shocking the defenders and energizing the attackers into a frenzy as they

trampled over dead and wounded bodies, wedged a lane through the crush of

struggling bodies and reached the edge of the cornfields that spread away to

the west in front of the McGeehee house.

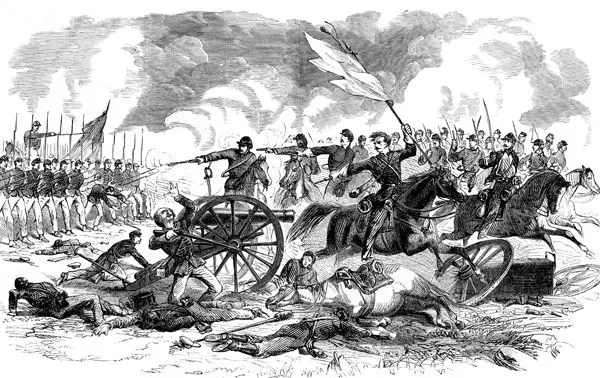

But, just as the rebel breakthrough was happening, a section of Union artillery came bounding and banging up the wagon road that runs near where the McGeehee house sits. Shaking the traces and whipping the haunches of the horses, the Union cannoneers swung the gun carriages off the road into a corn field and, circling around the fringe of the scrimmage of mad fighters, they came to a stop behind a snake wood fence. Instantly the cannoneers leaped from their perches on the limber boxes and, in less than a minute, they had their pieces spraying the storming front of the wild-eyed rebels with clumps of iron shot the size of baseballs. The fire of the cannon staggered the rebel soldiers, dwindling their numbers down to fragments of regiments, but they fought on like hellions for almost another hour, their angry eyes ablaze behind their blazing rifles, until, finally, reserves of Union infantry came up and poured massed volleys of lead into their crumbling flanks and they faded grudgingly back into the forest.

|

At the same time this was happening, a quarter mile farther to the north, another of Hill's attacks was being beaten back. A mass of his men had came through the woods to the brow of the hill overlooking the main channel of Boatswain Creek. For a moment, they had hesitated at the rim, dressing their line, making ready to plunge down the tree strewn slope to the ravine below. In that moment, a billowing roll of blue-black smoke suddenly laced the trees midway up the opposite slope for two hundred yards. A millisecond later, a blast of bullets surged against the rebel front like wind-driven sleet, ripping huge gashes in their line. Like men caught out of doors in a hurricane, Hill's soldiers involuntarily bent forward at the waist and staggered backwards on wobbly legs. Then, as if they had the means to communicate among themselves by telepathy, they all flopped on their bellies and cringed against the ground as sheets of lead punished the earth around them and the whirring shells from Union cannon exploded above them.

All over the farm fields they had crossed over, from the Cold Harbor Road to the brow of the creek valley, wounded and maimed rebel soldiers were dragging themselves away from the squall of iron sleet and hail. Some used their hands, dragging their shattered legs. Others used their knees, the bloody stumps of arms blown away hanging limply at their sides. Alone or with another, some in clusters of twos and threes, they moved rearward through a floating haze of smoke like a stuporous swarm of crabs emersed in fog from the sea.

Soon another wave of men—this time Hill's Georgia Brigade—came from the fields and moved toward the tree line where the previous waves had crashed. Walking at first, then running, the Georgians tried to reach the woods in order, but a sheaf of shells lobbed over the tree line of the creek and exploded in star bursts over their ranks. Fragments of metal from the Union shells ripped into their bodies, flipping them about in the air like rag dolls. Despite the startling rush of shells, the rebel throng, their red flags bobbing amongst them, bent their heads against the iron tempest and kept coming across the field. Firing, loading, and firing again, the soldiers in front fell, one by one, but their spots were taken by others, who fired and reloaded and fell in turn, the last man a little in advance of those who had fallen before. Finally, the ebb and flow of the waves of men commingled, and, thus replenished, they moved on as one to the edge of the creek valley, bounding like greyhounds down the slope toward the creek, leaping over fallen trunks of trees, twisting their bodies through clumps of wild azalea and blueberry brambles and reaching the bottom in tumultuous disorder.

At the creek bed, their wildly accelerating charge crashed into a wall of fire, a blast of converging rifle fire and canister from the opposite side. Staggering back into the thickets, their dead and wounded scattered over the whole breath of the slope and in the shallow water of creek bottom, the survivors crouched down behind rocks and tree stumps, in crevices and holes, and blindly fired back.

The little valley now became obscured by a dense bluish-white smoke, pooling like fog along the stream bottom, punctuated with bright flashes of gold, isolating each individual fighter as completely as if he was adrift in a boat on an empty ocean. Taking advantage, the uninjured among the attackers slide down the bank into the stream and, splashing through the muck, crawled into the thickets in front of the first tier of Union defenders. Crowding into the thickets, they bunched up and rushed upon the enemy and found themselves suddenly tumbling into fifty yards of almost empty trenches. They were in a gap between the flanks of two Union regiments. By sheer momentum they fought the sparse defenders hand to hand. Cursing with rage they used their rifles like clubs in the close quarters, bludgeoning their enemies to the ground, stomping and kicking savagely at their limbs and faces until the soles of their shoes were red.

Suddenly, from the second tier of Union trenches, a mob of Pennsylvanians rushed down the slope of the valley to the berm of the trench and fired a volley into the Georgians at point blank range. In an instant several dozen rebels fell backwards against the opposite wall of the trench mortally wounded. The survivors dived over the trench wall and disappeared in the thick smoke, slithering like snakes through the underbrush and tumbling into the creek bed.

From his vantage point, back by the Cold Harbor Road, A.P. Hill looked over the field to the tree line that fringed the creek valley. The field was littered with the dead bodies of his soldiers, and he saw crowds of wounded hobbling toward him. Broken gun carriages and pieces of splintered caissons were scattered about. He heard the sound of rifle fire fall away to a spattering, and he knew the attacks had broken the back of his division. In four hours of fighting, the division had lost its organization, suffered over five thousand casualties, and gained only momentary penetrations.

In the lull that

followed the retreat of the Georgians from the Union trenches, General Lee was

a half mile behind Hill, on a wooded knoll overlooking the bridge crossing at

Gaines Mill. He held binoculars in his hands and from time to time examined the

fields where Hill's soldiers were regrouping. From this and listening to the

distant battle sounds, he knew the battle in the creek valley was ended.

In the lull that

followed the retreat of the Georgians from the Union trenches, General Lee was

a half mile behind Hill, on a wooded knoll overlooking the bridge crossing at

Gaines Mill. He held binoculars in his hands and from time to time examined the

fields where Hill's soldiers were regrouping. From this and listening to the

distant battle sounds, he knew the battle in the creek valley was ended.

From all directions couriers arrived and departed with dispatches. Two of his aides, Walter Taylor and Charles Marshall, took the couriers' reports and passed him the information and he gave them instructions to relay. When they were alone again, he stepped away from his aides to where Traveller was tied to a tree. He put his binoculars in a case attached to the pommel of his saddle.

Traveller turned his head at this, and Lee came forward and stroked the stallion's black muzzle with a hand, his thoughts now on McClellan and the next phase of the battle. He had ordered Hill's attacks as a means of testing Porter's front, probing for weak spots, while he waited to see whether McClellan meant to threaten his flanks. During Hill's battle, Jackson's command had reached Old Church, with Stuart's cavalry going as far as the railroad, but to Lee's surprise Jackson's report was that there was no sign of McClellan. The road was empty down to the river. On the right flank, Longstreet's column had moved toward Porter's position along the river bank, watching for signs McClellan was building up force in Porter's rear, but his scouts, too, reported nothing materializing.

Lee glanced at the sun. It was about 3 o'clock. Only four hours of daylight left. If McClellan's counterattack was coming from the direction of the railroad, it would have developed by now. But McClellan still has time to cross more corps by the bridges behind Porter's position and fight us straight up, he thought.

"Well, old boy, let's we find out what Little Mac means to do," he said as he stripped Traveller's reins loose from the tree and walked him to the edge of the knoll where Taylor and Marshall were standing.

He stepped between the young men and looked over the battlefield again. Except for the occasional sound of cannon fire there was a strange quiet. The battle torn fields in front of the woodland covering Boatswain Creek were clear of Hill's wounded. There were several regiments—Hill's reserve—lying on their arms along the shoulders of the Cold Harbor Road. Teams of artillery horses, dragging refurbished batteries of cannon, were kicking up whirls of dust from the ruts.

Lee looked first at Taylor, then at Marshall. "Tell General Longstreet he must get his division up and be ready to attack the enemy's left in two hours." "Tell General Hill I know his men are battered, but they must hold the ground gained in the center at all cost. Tell him his men will be relieved when Jackson comes up." Nodding to his aides to be off, he vaulted into the saddle with a careless grace. "We will be found over there," he said as he led Traveller east toward Beulah Church.

On the opposite side of Boatswain Creek, as Lee was riding east, Fitz John Porter was taking stock of things. The reports from his brigade commanders told him of the penetrations and casualties the rebel attacks had caused—he had lost thirty percent of his force in the struggle—and he ordered up fresh brigades from his reserve. This left him with only two brigades in reserve, so he sent a dispatch to McClellan explaining the status of his forces and asking where Slocum was. Then he called for his horse and rode across the plateau to his left flank and worked his way to his center and then his right flank, looking for deficiencies as he went and ordering their correction.

As he made the circuit of the field, he heard the woods stirring again with ominous sounds—the trills of bugles, the rattling of artillery carriage wheels, the confused buzz of soldiers' voices, the strident commands of field officers, and the humming tread of innumerable feet on the thick mat of dry leaves covering the forest floor. Lee will use me up this time, he thought. Hurriedly, he ordered up to the front lines the rest of his infantry reserve and sent a second staff officer riding to McClellan, this time requesting a corps be sent across the river.

By late afternoon, the sounds of battle rose again to a thunderous roar of noise along Boatswain Creek. The wild cheering of the men, the rifle volleys, sounding like the backfiring at a thousand revving engines, the incessant cannonading, the sounds rolling along the fighting front from one end to the other and back again. Again and again, first here, then there, the rebels came pouring into the creek valley and into the corn fields along the flat land, surging up to the enemy and grappling with them under the fierce fire of their rifles and shells. Finally, despite the stress of canister fire, a fresh brigade of rebels swept down into the creek bottom at a dead run and threw themselves against the opposite bank as the Union infantry in the trenches blasted them with rifle volleys. Then, as the pressure of the rebels against the first line of trenches increased in intensity, two batteries of rebel field pieces—twelve Napoleons—opened from the fields above the creek valley and the slope on the Union side of the creek became artillery hell.

As the cannoneers manning the Union guns on the plateau racheted up the elevation of their gun tubes to answer this, flights of rebel shells swooped over the creek like birds of prey and slammed into the wooden barricades with deafening impacts, smashing the timbers into matchwood and hurling huge splinters in every direction. As the rebel shells crashed down, a band of Tennesseeans, clutching their rifles like clubs, scrambled over the bank and raced up the slope with curdling yells and screams, and, rushing through the jagged gaps in the first line of barricades, they fought the enemy hand to hand at the second tier. But yet again, Union reinforcements came sweeping down the slope into the contested space and forced the enemy out.

About the time of this repulse, General Lee reached the ravine that empties the shallow waters of Bloody Run into Dr. Gaines's mill pond. Passing it, he led Traveller into a large cotton field owned by a planter named Allerson and stopped. Ahead of him, a huge dust cloud towered above the pine trees and dusty ranks of Stonewall Jackson's soldiers were streaming past Beulah Church toward the Cold Harbor Road and Boatswain Creek.

Listening to the sounds of the battle reverberating in the weltering atmosphere, Lee nudged Traveller into a tight circling walk around the simmering white field, his eyes taking in the three fingers of ravines that spread into the cotton field from the east. Looking west across the Cold Harbor Road, he saw aligned with them, in the waist of the plateau where the Watt house stands, the tips of the two ravines the streamlets of Boatswain Creek run through. Three weeks before, when his operations against McClellan were in the planning stage, he had seen these ravines marked on a map and selected their location as his line of defense, for it was here that he had expected his center to fight George McClellan for his base.

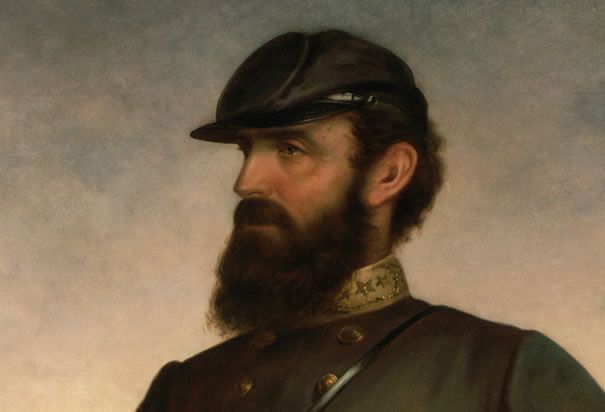

Turning in the saddle, General Lee saw the wiry figure of a horseman appear on the Allerson farm lane, riding toward him on a little sorrel horse. The visor of the rider's cap partially obscured his face and the rest was covered by a straggly beard, but Lee knew immediately it was Stonewall and he nodded his head in satisfaction. Here was a soldier who was his perfect match—a hard core spirit afraid of nothing, always willing to push his men to the limit of exertion if there was any chance of crippling the enemy. Give him a direction and off he would go with no objections. Lee raised his hand in greeting and led Traveller forward to meet him. Together, we can push the enemy out of Virginia, he thought.

Twenty yards down the lane, the two soldiers came together and reined up. Stirrup to stirrup, they hunched together over the pommels of their saddles and quietly discussed the progress of the battle.

A half hour later, Fitz John Porter was standing on the porch of the Watt house when one of his staff officers called to him excitedly, "Look, General, look, they're coming at our right again!"