| Read all the Civil War Sesquicentennial articles | Comments and Questions to the Author |

The War in the East June 1862

I

Lincoln Holds The Ribbons In His Hands

In

1952, T. Harry Williams, an award-winning historian from Louisiana State University, wrote, in his book, Lincoln and his Generals: "Judged by

modern standards, Lincoln stands out as a great natural strategist, a better

one than any of his generals. He [did] more than Grant or any other general to

win the war for the Union." In contrast to Mr. Williams's opinion, however,

the objective record of history shows that Lincoln did more than any of his

generals to prolong the war and thereby double the casualties and the

destruction it caused. The issue this fact raises is, was it justified?

In

1952, T. Harry Williams, an award-winning historian from Louisiana State University, wrote, in his book, Lincoln and his Generals: "Judged by

modern standards, Lincoln stands out as a great natural strategist, a better

one than any of his generals. He [did] more than Grant or any other general to

win the war for the Union." In contrast to Mr. Williams's opinion, however,

the objective record of history shows that Lincoln did more than any of his

generals to prolong the war and thereby double the casualties and the

destruction it caused. The issue this fact raises is, was it justified?

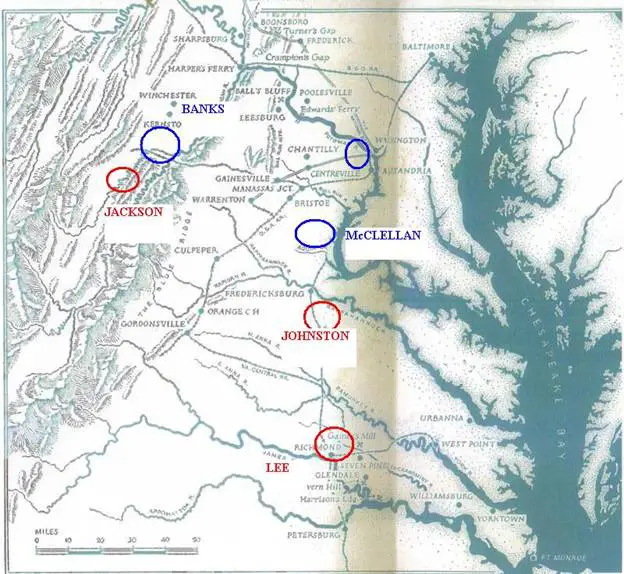

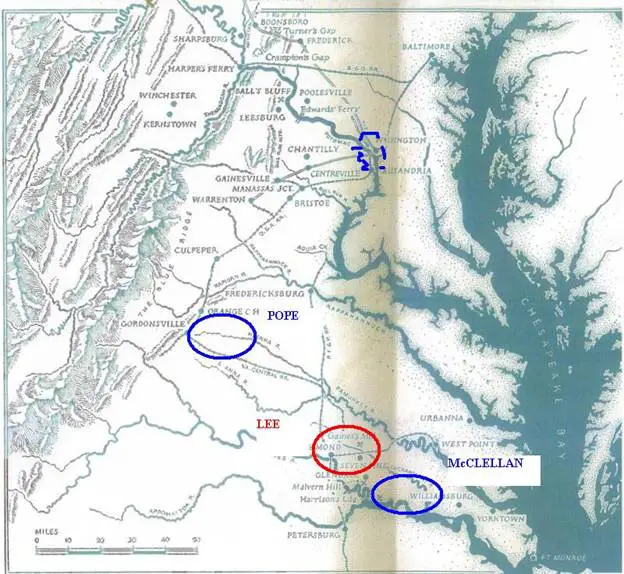

The proof of the verdict lies in what happened in the East, in 1862; beginning with Lincoln's decision, in June, to divert military force, from McClellan's effort to capture Richmond, to a fruitless effort to destroy Stonewall Jackson's force operating in the Shenandoah Valley; and ending with his decision—in July―to raise the siege of Richmond.

On June 1, 1862 President Abraham Lincoln must have felt pretty good about the course the war had taken. Orchestrated primarily by Illinois men, the Western armies, under the command of Major-General Henry Halleck, had brought Missouri and Kentucky completely within the control of the Union, had driven the rebel army out of Western Tennessee, and were moving to consolidate their gains and take control of Eastern Tennessee. In the East, under the command of Major-General George B. McClellan, the Army of the Potomac was gaining an increasingly strong foothold in the suburbs of the Confederate Capital, poised to begin a bombardment that eventually would cause its capitulation. With that done, the rebellion would soon be crushed out as the Union armies, acting in concert, converged on the rebel heartland of Georgia: a rosy appearing situation, indeed, for the Union President. But the reality would prove to be far different: two more hard years of total war against the Southern civilian population would pass before the surrender, this caused in large measure by the decisions Lincoln made in his role as Commander-in-Chief, in June 1862

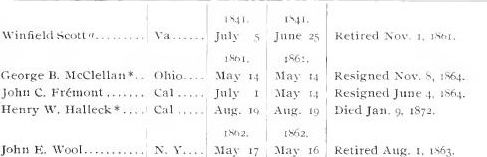

First Five Union Regular Army Major-Generals

First Five Confederate Regular Army Major-Generals

Samuel Cooper*

Albert Sidney Johnston*

Robert E. Lee*

Joseph E. Johnston*

Pierre Beauregard*

*West Point graduates

Note: It is a curious thing that, of the first five major-generals appointed by Lincoln at the outset of the war, two were considered Californians. (Both Scott and Wool were at the end of long army careers when the war came in 1861) Henry Halleck was a captain of engineers when he resigned his army commission in 1852. He became a lawyer specializing in land titles, a banker, and a land developer in San Francisco. He had served as California's first secretary of State, was a long-time supporter of Stephen A. Douglas, and, as the war approached, became the major-general commanding California's tiny militia. Fremont, like Halleck, had served in California during the War with Mexico. In command of a small force, he had led the short-lived Bear Flag Republic revolt against Mexican authority; then, embroiling himself in controversy with Brigadier-General Kearny, he was court martialed and found guilty on the charge of mutiny; granted clemency by President Polk, he resigned his commission as a captain of topographical engineers in 1848. Returning to California by a difficult route, in 1849, he eventually settled on the Mariposas Tract (now Mariposa County), seventy square miles of land in the Western Sierra foothills. (Where he got the money for this is another story) Making Monterey his base, Fremont became involved in State politics, and as a Democrat was appointed one of California's first senators. By 1855, he was adopted by the fledging Republican Party as its first candidate for President, this due to the fact that he was a popular figure because of his published writings about his several spectacular treks across the Rockies.

With such credentials, from a strictly military point of view, it is difficult to understand why Lincoln appointed these two men to the top rank of major-generals in the Regular Army. The explanation must lie in the politics.

It is important to note, also, that of the first five Regular Army major-generals Lincoln appointed, only one—George McClellan, with the exception of Fremont fighting Jackson at Cross Keys―actually commanded an army in a Civil War battle; he during the Seven Days and at Antietam. In contrast, of President's Davis's first five picks, four of them commanded repeatedly Confederate armies in heavy Civil War battles.

Lincoln came to the role of Commander-in-Chief knowing that, in a war between the States, the Union possessed such an overwhelming advantage, in manpower, in sea power, in natural resources, in manufacturing capacity, and in financial strength, that it was objectively impossible for it to lose the war—unless Great Britain were to commit its navy to the mission of breaking the Union blockade of Southern ports.

Lincoln's clear view of the "big picture" brought his mind to the conclusion that the best policy to adopt in waging the war in the East, was to accept no risk that Washington might be occupied by the enemy, even if it were but for a day; for, if this happened, Lincoln was certain in his mind that Great Britain would immediately use its war ships to escort its commercial vessels to Charleston Harbor. And suddenly the tables would be turned, and the permanent break up of the Union almost assured.

In pursuing this policy of security for Washington in the East, Lincoln had no reason to interfere with military operations in the West. Illinois was a key State that Lincoln knew he could rely upon for aggressive prosecution of the war in the West. The State, wedged between Missouri and Kentucky, with the Mississippi River providing its commercial life's breath, provided the war effort with a deep, almost bottomless, pool of young men; and, because of this, Lincoln quickly appointed Illinois politicians, like Stephen Hurlbut, John McClernand, and Benjamin Prentiss, to positions of command, as well as West Point-trained Regular Army officers who lived in Illinois, like John Pope and Ulysses S. Grant.

First sending John C. Fremont, and then as Fremont's replacement, Henry Halleck, to command the armies of the West, Lincoln let the military situation there evolve at its own pace, until, with Corinth captured, he eventually became impatient with Don Carlos Buell.

But, in the East, from the moment of the war's beginning, Lincoln had taken direct control of military operations, focused on gaining territory for the Union while, at the same time, guaranteeing security for Washington. He had selected Irvin McDowell, then a young major, to command the army of ninety-day volunteers he had received from the governors of the loyal States, making him overnight a brigadier-general in the Regular Army. In conformance to his orders, McDowell had moved this fledging army against the rebel defenses at Bull Run which resulted in its collapse and wild flight back to newly built forts surrounding Washington. Then, Lincoln had selected George B. McClellan, a brilliant young engineer and retired Regular Army officer, to organize two hundred thousand three year volunteers into a new army. This done, he grudgingly acquiesced in McClellan's plan to move the army by water to the head of the York River and lay siege to Richmond. Almost as soon as McClellan's operation was in motion, however, Lincoln began to hedge.

The

reasons for this appear to be several. First, as always with Lincoln, there was

the influence of politics affecting his actions. John Frémont had a great

public following and substantial support among the Radical Republicans in Congress,

who were pressing Lincoln to make the abolition of slavery, the object of the

war. A place in the military picture had to be found for Fremont despite his misconduct in Missouri, which had led Lincoln to relieve him of duty.

To create it, Lincoln developed the idea of a "departmental system."

Dividing the territory of Virginia into sections, he assigned generals to

command troops within specific geographic areas while he assumed direct command

over all. In this way, Lincoln expected to gain territory across a broad front,

extending from the Appalachians on the western border of Virginia, to Richmond in the east. If the use of this system relieved Lincoln of political pressure

brought to bear against him by Frémont's friends, it produced a new tension more

severe. From its inception, Lincoln was under constant pressure, from one

department or another, to provide more troops and he reconciled the competing

demands, by pulling troops repeatedly from McClellan's operation against Richmond.

The

reasons for this appear to be several. First, as always with Lincoln, there was

the influence of politics affecting his actions. John Frémont had a great

public following and substantial support among the Radical Republicans in Congress,

who were pressing Lincoln to make the abolition of slavery, the object of the

war. A place in the military picture had to be found for Fremont despite his misconduct in Missouri, which had led Lincoln to relieve him of duty.

To create it, Lincoln developed the idea of a "departmental system."

Dividing the territory of Virginia into sections, he assigned generals to

command troops within specific geographic areas while he assumed direct command

over all. In this way, Lincoln expected to gain territory across a broad front,

extending from the Appalachians on the western border of Virginia, to Richmond in the east. If the use of this system relieved Lincoln of political pressure

brought to bear against him by Frémont's friends, it produced a new tension more

severe. From its inception, Lincoln was under constant pressure, from one

department or another, to provide more troops and he reconciled the competing

demands, by pulling troops repeatedly from McClellan's operation against Richmond.

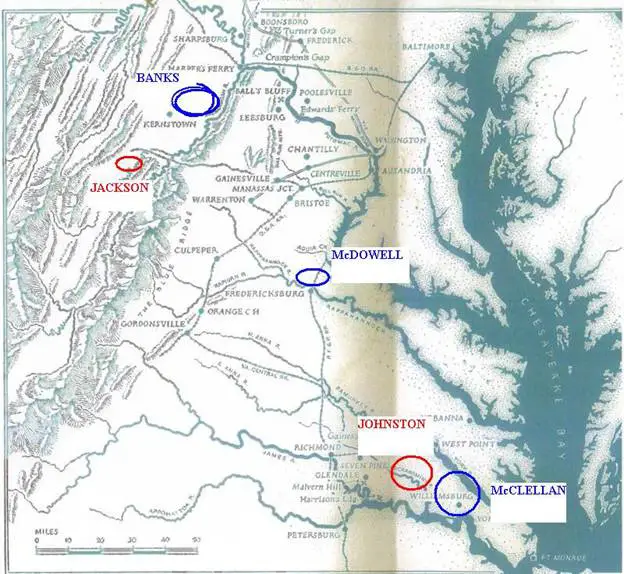

At the vortex of this pressure was Irvin McDowell's corps. Though the fiasco at Bull Run was hardly his fault―the battle was instigated by Lincoln against McDowell's advice—McDowell's star had been badly tarnished and he fell from the Republicans' grace. Reducing McDowell's command to a corps, instead of an army, Lincoln had removed McDowell's corps from McClellan's army and used it to guard the Department of the Rappahannock, the gateway to the Manassas Plain and Washington.

The decision to do this, seems, fairly, to reflect Lincoln's developing loss of confidence in McClellan. In the immediate weeks after the Battle of Bull Run, George McClellan made an excellent impression on everyone in Washington. The new three year volunteers were pouring into collection camps in the several States; then, mustering into the United States Volunteer Army they were organized into companies and sent off to Washington where McClellan's officer staff assembled them, first, into regiments, and then brigades; outfitting them in the process with the immense amount of materiel required to support them in the field. Starting essentially from scratch, within three months McClellan had formed an army of over one hundred thousand drilled soldiers, supported by immense wagon trains, batteries of artillery, and cavalry.

During this time, though, McClellan's personality and character began to wear on Lincoln. Once he saw the full army on parade, with all its banners flying, the serried ranks marching past him in perfect formation, Lincoln, understandably, wanted it committed to action immediately. Lincoln knew the Union masses outnumbered their Confederate counterparts grossly, and, to his mind, this meant the weight of the former must certainly press down eventually the weight of the latter; so the sooner the effort began in earnest―and to hell with the body bags—the sooner the war would be won.

Pressing this view upon McClellan, Lincoln found McClellan resisting and the friction that developed at the pressure point very quickly resulted in the evaporation of any semblance of a personal relationship existing between the two men. That McClellan was right to hold the army back from battle, and Lincoln wrong in wishing for it, McClellan's force of character was too weak to bring Lincoln to his point of view without alienating him. This was Mac's gross fault, his immaturity at the age of thirty-six to deal effectively with his fifty-six year old superior. Had he been Lee the outcome between the two men certainly would have been different.

II

Lincoln Blunders, or Does He?

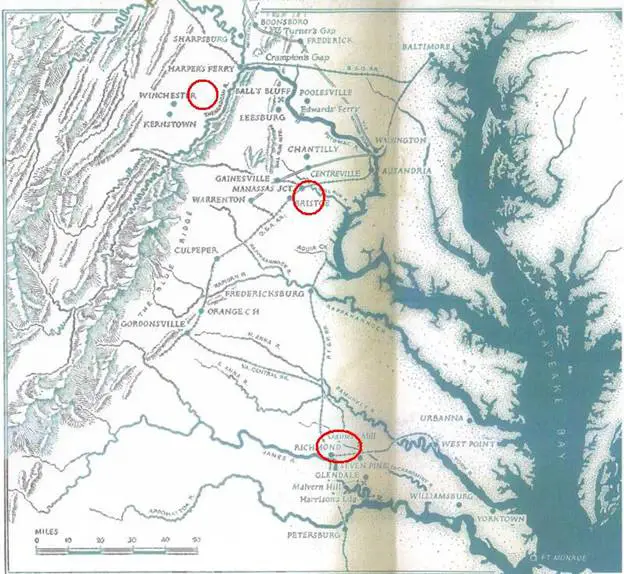

The tug between Lincoln and McClellan came to a final head in late May 1862, when, for the second time, Lincoln had changed his mind about releasing Irvin McDowell's corps to join McClellan's army before Richmond. On May 25, just after authorizing McDowell to begin the movement from the Rappahannock, Lincoln countermanded the order. The ostensible reason he did this, is set forth in a telegram he sent to McClellan on May 31, 1862.

Washington D.C.

May 31, 1862 10:20 p.m.

Major Gen. McClellan

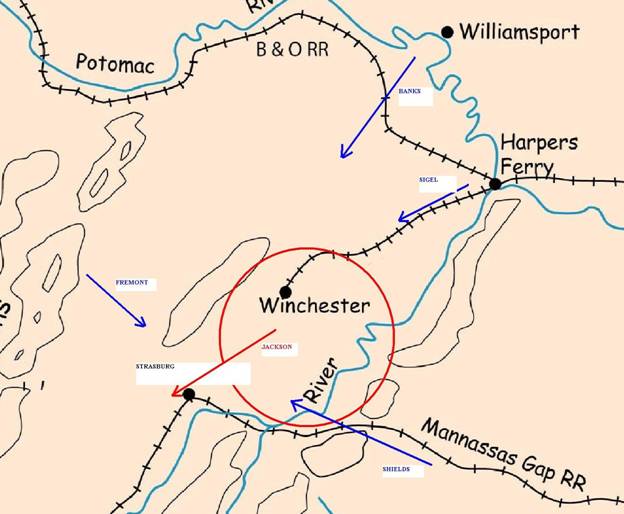

A circle whose circumference shall pass through Harper's Ferry, Front Royal, and Strasburg, and whose center shall be a little northeast of Winchester, almost certainly has within it this morning, the forces of Jackson, Ewell, and Edward Johnson. Some part of these forces attacked Harper's Ferry at dark last evening, and are still in sight this morning. Shields―with McDowell's advance, re-took Front Royal at 11:00 a.m. yesterday. Fremont, from the direction of Moorefield, promises to be at or near Strasburg at 5:00 p.m. today. Banks, at Williamsport, with his old force, and his new force at Harper's Ferry, is directed to cooperate.

A. Lincoln

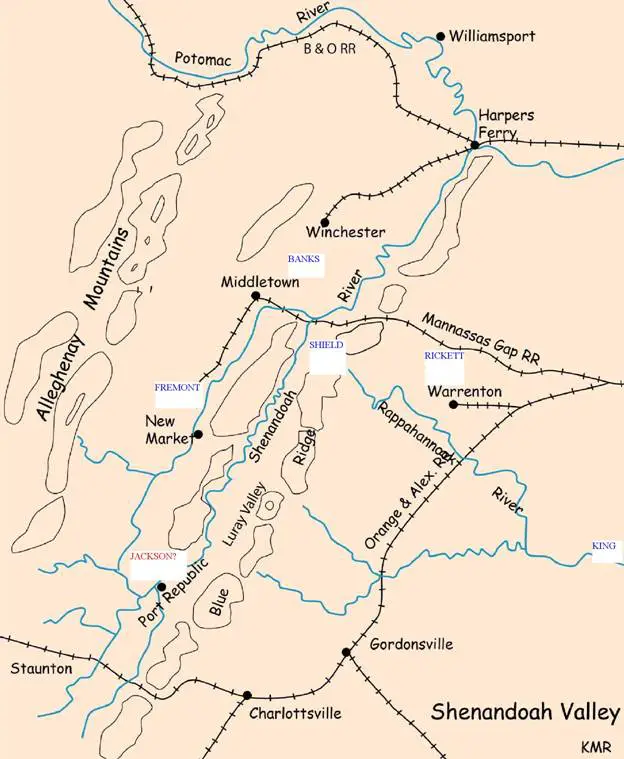

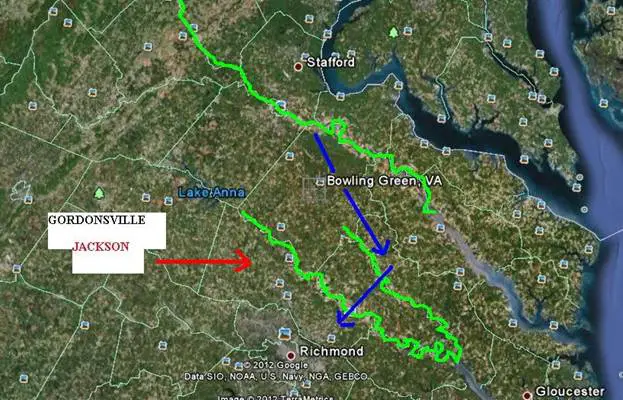

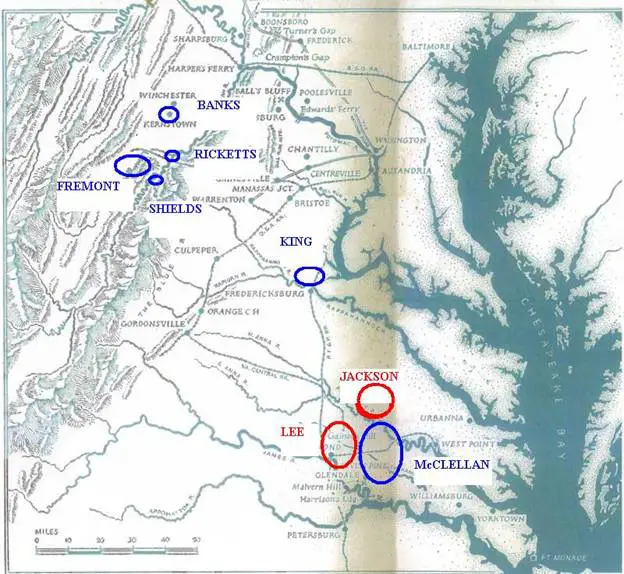

Jackson's Presence Around Winchester Lasted Five Days

By June 15, Jackson is at Charlottesville, moving toward Richmond

But what was Lincoln's real reason for stopping McDowell from marching? He knew, from reports received, that Jackson was operating with three divisions: his own, Richard Ewell's, and Edward Johnson's, a force of about 15,000 men. Against this, Lincoln brought Fremont's corps, totaling about 30,000, Shield's division, about 10,000 men, and Banks's corps, about 15,000 men; requiring Fremont to march from Franklin to Moorfield to Strasburg to Harrisonburg while Shields marched from about Fredericksburg to Front Royal and Strasburg and then down the Luray Valley to Port Republic. The marching effort totally fagged both forces, leaving them out of action for about six weeks. During the entire exercise Lincoln knew there was no chance that Jackson's movement might translate into danger to the security of Washington. So why did he do it?

Since he assumed the role of directly controlling all military movements in the East, in March 1862, he had been advised by Ethan Hitchcock and the so-called "War Board," but the Rebellion Record and his own papers contains nothing which suggests either Hitchcock or the Board endorsed the decision to abort McDowell's movement to Richmond and instead race it into the Shenandoah Valley to squash Jackson.

Certainly he got no support from regular army officers in the field. Here is the record.

War Department

May 24, 1862, 11:12 a.m.

Major-General McDowell, Falmouth

In view of the operations of the enemy on the line of General Banks the President thinks the whole force you designed to move from Fredericksburg should not be taken away, and he therefore directs that one brigade in addition to what you designed to leave at Fredericksburg should be left there.

Edwin Stanton

Note: It appears that a reasonable decision has been made to continue McDowell's movement to Richmond, despite the disruption to "Bank's line" that Jackson's movement has caused; but then, five hours later McDowell gets this.

War Department

May 24, 1862, 5:00 p.m.

Major-General McDowell, Fredericksburg

General Fremont has been ordered by telegraph to move from Franklin to Harrisonburg to capture or destroy Jackson's forces.

You are instructed, laying aside for the present the movement on Richmond, to put 20,000 men in motion at once for the Shenandoah Valley, moving on the line of the Manassas Gap Railroad. Your objective is to capture Jackson's forces either in cooperation with Fremont or alone, in case of want of supplies or if transportation interferes with his movements. Reports say that Banks is now fighting with Jackson eight miles north of Winchester.

A. Lincoln

Note: What prompted this decision in Lincoln? Although the Rebellion Record is silent about this, the answer, in part, must depend on what was Fremont's response to Lincoln's order. But the major part deals with Lincoln's interest in holding territory, rather than capturing strategic points. Or does it simply demonstrate Lincoln's loss of confidence in McClellan?

When Lincoln, in March, assumed, in essence, field command of the Eastern armies, he had in his mind's eye, as a prime objective, the capture of Knoxville and Chattanooga. To accomplish this, he had set up John Fremont (who he had just relieved from command of the Department of Missouri) in command of the "Mountain Department," promising to assemble for Fremont's use, 35,000 men. To do this, among other things, he took Blenker's division from McClellan and gave it to Fremont. How Lincoln could have seriously believed it was possible, much less probable, that Fremont could reach Knoxville no historian seems to comprehend. It is 426 miles from Moorfield, West Virginia, to Knoxville, Tennessee. How Fremont was supposed to be able to keep his column supplied during this incredible march through the Appalachian Mountains, no endorser of Lincoln's brilliance as an army commander can say. By the time he received Lincoln's order to move east to Harrisonburg, to get across Jackson's communications, Fremont had gotten no closer to Knoxville than Franklin, West Virginia, 300 miles away.

Fremont responded to Lincoln's order, first, with the statement that "if I abandon this line (toward Knoxville) and move eastward to support Banks this whole country of the Ohio would be thrown open." Suddenly, in Lincoln's mind, concentrating against Jackson's 15,000 men, over 40,000 men, had become more important than his plan of getting Fremont's force to Knoxville? Fremont's second response, late on May 24, acknowledged the order but without Lincoln grasping the point, changed it. Fremont wrote, "will move as ordered and operate against the enemy in such a way to afford prompt relief to Banks." Instead of moving east to Harrisonburg, Fremont moved north via Moorfield to Strasburg. Fremont is willing to move, but not willing to take direction how to do it.

Lincoln, apparently foretelling that Fremont would not contain Jackson by himself, and knowing Banks was too weak to do it, threw two major operations—Fremont's on Knoxville and McClellan's on Richmond―into disarray, just for the chance of crushing Jackson. What was the man thinking? Anyone?

Washington City

May 24, 1862 8:00 p.m.

Major-General McDowell

I am highly gratified by your alacrity in obeying my order. The change was as painful to me as it can possibly be to you. Everything now depends upon the celerity and vigor of your movement.

A. Lincoln

Note: "Everything now depends upon. . . your movement?" What does Lincoln mean, here? "Everything?" The war effort? The safety of Washington? Or merely the capture of Jackson? All that has happened is that, for a brief moment in time, an enemy force of 15,000 has "breached the paper line" that runs from Richmond to Corinth—a line Lincoln had arbitrarily drawn. To repair this "breach," Lincoln insists on leaving McClellan's right flank dangling in the air, at Richmond. Just impossible to understand, unless he is using Jackson's presence in the lower Shenandoah Valley as a mask to hide the fact that he does not think McClellan will be successful in his endeavor, and wants to give him no more men. But then McClellan will certainly not be successful, without the same control of force Henry Halleck enjoyed in the approach to Corinth.

Stonewall Jackson in the Valley |

Headquarters, Department of the Rappahannock

May 24, 1862 9:00 p.m.

His Excellency, the President

I obeyed your order immediately and perhaps there as a subordinate I ought to stop; but I trust I may be allowed to say something. I beg to say that cooperation between myself and Fremont to cut Jackson is not to be counted upon, even if it is not a practical impossibility. I am entirely beyond helping distance of Banks. A glance at the map shows that the line of retreat of Jackson's force up the valley is shorter than mine to go against him. It will take a week to ten days for the force to get to the valley and by that time Jackson will be gone. I shall gain nothing for you there and shall lose much for you here. Your order throws us all back. We shall have all our large forces paralyzed.

Irvin McDowell

Note: McDowell is certainly mincing no words here and he is correctly predicting the result. And now, as his operation against Jackson unravels into fiasco, Lincoln decides he better get out of the field command business, by bringing John Pope from the West to take command of the Virginia forces not in McClellan's hands.

Washington City, June 9, 1862

Maj.Gen. Fremont

Halt at Harrisonburg, pursuing Jackson no farther. Stand on the defensive and await further orders I will send you.

A. Lincoln

Note: At the outset of this affair, one explanation for Lincoln issuing direct orders to commanders, is that Fremont ranked every other general in the East, except McClellan; since Lincoln had stripped McClellan of his status as general-in-chief, there was no one available with the rank, except Lincoln, to give Fremont orders. Apparently, Lincoln no more trusted Fremont to act the role of theater commander than he did McClellan; and these are two of the three highest contemporary ranking generals on his list. Compare this to Davis's list where four of the five highest ranking generals exercised theater command repeatedly throughout the war.

Washington City, June 13, 1862

Maj. Gen. Fremont

We cannot afford to keep your force, and Banks's, and McDowell's, engaged in keeping Jackson south of Strasburg and Front Royal. Jackson can have no substantial reinforcement, so long as a battle is pending at Richmond. Surely you and Banks in supporting distance are capable of keeping him from returning to Winchester. But if Sigel is sent to you, and McDowell be put to other work, Jackson will break through at Front Royal again. Please do as I directed in the order of the 8th and neither you nor Banks will be overwhelmed by Jackson.

A. Lincoln

Note: In response to Lincoln's "please,"Fremont wrote: "I ought to have a force of 30,000 men. I should also have the power to order the procurement of supplies immediately.

Washington City, June 15, 1862

Maj.Gen. Fremont

If Jackson comes upon you with superior force you have but to notify us, fall back cautiously, and Banks will join you in due time. We cannot put both you and Banks on the Strasburg line, and leave no force at Front Royal. We need you on one line and Banks on the other so if Jackson moves, you can concentrate to defeat him.

A. Lincoln

III

Lincoln Reshuffles The Command Structure

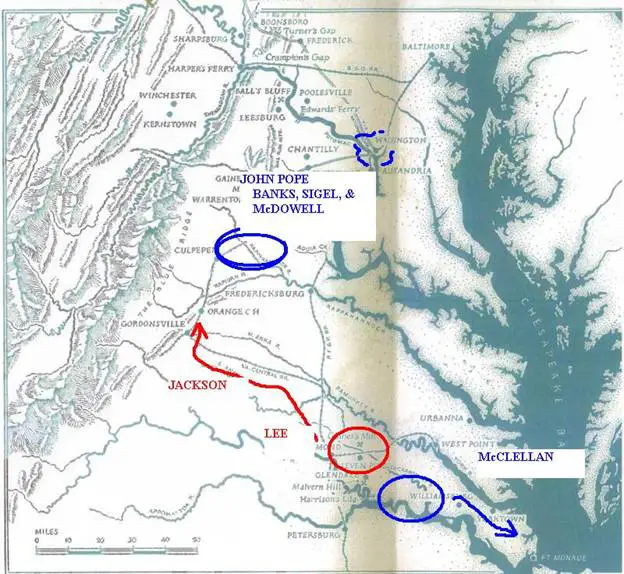

Soon after sending this last quoted message to Fremont, Lincoln was informed that a force had been detached from the rebel army at Richmond and sent west to reinforce Jackson's force which was then lurking in the Blue Ridge's Swift Run Gap. Given the sequence of events that thereafter quickly unfolded, it is reasonable to conclude that the receipt of this intelligence caused Lincoln to decide the arrangement of forces outside McClellan's control needed to be reconfigured under a command other than his. Perhaps he envisioned Jackson, now reinforced, advancing again to "breach" the Union "line" he had drawn across the map. Perhaps, it was a simple matter of restructuring the forces that had been operating independently of each other, into a single cohesive force that could cooperate with McClellan's army in the struggle to capture Richmond. Instead of Lincoln giving direct orders to three or more army commanders, he could give them to one who could presumably move the others to execute them. Perhaps, too, it was a matter of party politics. Whatever were the motivating factors, Lincoln's criteria for the selection is reasonably plain: The man chosen had to be someone he was personally comfortable with, someone he thought would unhesitatingly execute his orders, someone whose politics reflected his own, someone who had developed a public reputation of aggressive and successful handling of a force comparable in size to that which he was being called to command. The man he selected was John Pope.

John

Pope was a logical choice: he was from Illinois, his family had been close to

Lincoln before the war; he was a Republican; as a brigadier he had operated

successfully in a climate of guerilla warfare in North Missouri, and as a

major-general he had commanded an army of 20,000 men which had operated successfully

in East Missouri, capturing Madrid, Missouri, and Island No. Ten, and he had

cooperated with Halleck's other forces in the approach to Corinth. Pope's

military experience was well known to the general public and it entertained a

favorable impression of him. A negative was the fact that all three of the

existing corps commanders—Fremont, McDowell, and Banks―outranked him, but

that problem could easily be overcome simply by the President

"specially" appointing him to command the consolidated forces. Of

course, Lincoln knew that it was not likely that Fremont, outranked by no one

except McClellan, would accept demotion gracefully but he probably thought it a

good thing if Pope's appointment induced Fremont to resign, which it did.

John

Pope was a logical choice: he was from Illinois, his family had been close to

Lincoln before the war; he was a Republican; as a brigadier he had operated

successfully in a climate of guerilla warfare in North Missouri, and as a

major-general he had commanded an army of 20,000 men which had operated successfully

in East Missouri, capturing Madrid, Missouri, and Island No. Ten, and he had

cooperated with Halleck's other forces in the approach to Corinth. Pope's

military experience was well known to the general public and it entertained a

favorable impression of him. A negative was the fact that all three of the

existing corps commanders—Fremont, McDowell, and Banks―outranked him, but

that problem could easily be overcome simply by the President

"specially" appointing him to command the consolidated forces. Of

course, Lincoln knew that it was not likely that Fremont, outranked by no one

except McClellan, would accept demotion gracefully but he probably thought it a

good thing if Pope's appointment induced Fremont to resign, which it did.

On June 19, with McCall's division, of McDowell's corps, now with McClellan at Richmond, with Shields's division, as Lincoln so drolly put it, "out of shape, out at elbows, and out at toes," with Banks's corps worn out too, and Fremont's out of supplies in the valley, Lincoln had Stanton order Pope to come to Washington.

Pope arrived in Washington on June 24, to find that Lincoln was gone from the city. Where Lincoln went we know, but why he went there we can only guess. Sometime very late on Monday, June 23, Lincoln left Washington on a train and traveled to New York City. Reaching there early on Tuesday morning, he took a train to West Point and met privately with Winfield Scott. What the two men talked about, neither directly said. (Scott did write a memoir of his military career, but the book ends shortly after the fall of Fort Sumter.) John Eisenhower, Scott's modern biographer, in his 430 page book, devotes a paragraph to Lincoln's meeting with Scott, telling us, without reference to any source, that Lincoln "came to seek Scott's advice as to whether to risk exposing Washington to Confederate attack by sending the last large force, McDowell's corps, to reinforce McClellan."

Let's see: the President, when he knows a battle royal is about to unfold in front of Richmond, putting McClellan's army at risk of being seriously damaged, if not destroyed, disappears from Washington, for the purpose of traveling three hundred miles to ask an old general that he had dumped, in November 1861, whether it was prudent to send "the last large force, McDowell's corps, to reinforce McClellan." Then rush back to Washington, to meet John Pope.

Does

this make sense to anyone? The first obvious point is, what would be imprudent

about sending the "last large force" to Richmond? Would Scott have

told Lincoln that there was any reasonable chance that, with Richmond under

siege, the rebels might be able to attack Washington? Hardly

would Scott have told Lincoln that. The idea, given the circumstances of the

case, is patently ridiculous.

Does

this make sense to anyone? The first obvious point is, what would be imprudent

about sending the "last large force" to Richmond? Would Scott have

told Lincoln that there was any reasonable chance that, with Richmond under

siege, the rebels might be able to attack Washington? Hardly

would Scott have told Lincoln that. The idea, given the circumstances of the

case, is patently ridiculous.

The second point is Eisenhower's characterization of McDowell's corps, as the "last large force." It plainly was not. Fremont, according to Lincoln's own recorded calculations of the time, had about 30,000 men which was about the amount McDowell had at that time. And Banks had about 15,000 to 20,000 men at that time. Dix, at Baltimore, had at least 10,000 men, and Wadsworth, in command of the Washington defenses, had about 20,000 men. If Scott said anything on the subject, he would have told Lincoln to get McDowell going.

And that is what he did. The one piece of written evidence, constituting a supposed memorandum memorializing what Scott said to Lincoln, which Eisenhower ignores, reads this way:

"I consider the numbers and positions of Fremont and Banks, adequate to the protection of Washington against any force the enemy can bring by way of the upper Potomac, and the troops, at Manassas, with the garrisons of the Washington forts equally adequate to its protection on the south.

The force at Fredericksburg (McDowell's corps) seems entirely out of position, and it cannot be called up (now), directly and in time, by McClellan, from the want of railroad transportation (This Lincoln must have represented as a fact). If, however, there be sufficient vessels (which there were) at hand, that force might reach the head of the York River, in time to aid in the operations against Richmond. McDowell's force, at Manassas, might be ordered to Richmond, by being replaced by King's brigade.

The defeat of the rebels, at Richmond, or their forced retreat, thence, would be a virtual end of the rebellion, and soon entire Virginia would be restored to the Union. The remaining points to occupy are Mobile, Charleston, and Chattanooga. These must soon come within our hands.

Respectfully Submitted, Winfield Scott."

Notice that Scott's supposed memorandum, which is quoted in The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Vol 5, p. 284, says nothing about consolidating these independent commands into one army and operating the army independently of McClellan's. And, to the extent the memorandum does contain Scott's professional advice, the evidence is undisputed that Lincoln ignored it.

So why did Lincoln run off at this crucial moment to visit General Scott? The only reasonable explanation, given the circumstances, is to create the public impression that what he is about to do—essentially dump Fremont for Pope, in the process consolidating the available forces to make a second formidable army in the East―was endorsed, if not recommended, by Scott, the great warrior of the past who marched into Mexico with ten thousand men and brought its Government to its knees.

Here is what the New York Times reported Lincoln said publicly, at Jersey City on June 24, as he was returning to Washington.

"When birds and animals are looked at through a fog they are seen to disadvantage, and so it might be with you if I were to attempt to tell why I went to see General Scott. I can only say that my visit to West Point did not have the importance which has been attached to it; but it concerned matters that you understand quite as well as if I were to tell you all about them (Huh?) Now, I can only remark that it had nothing whatever to do with making or unmaking any General in the Country (Pope and Fremont) [Laughter and applause] The Secretary of War, you know, holds a pretty tight rein on the Press, and I'm afraid if I blab too much he might draw a tight rein on me."

Lincoln's speech is moronic, yet, given the fact that the evidence shows him to have been a clever, experienced, and successful trial lawyer, we must assume he was acting a pose: he used Scott by creating the illusion the change he made in army organization was based on Scott's advice. He certainly did not take the advice he got from Scott, and counted on Scott to keep his mouth shut

IV

Lincoln's Mind-Set

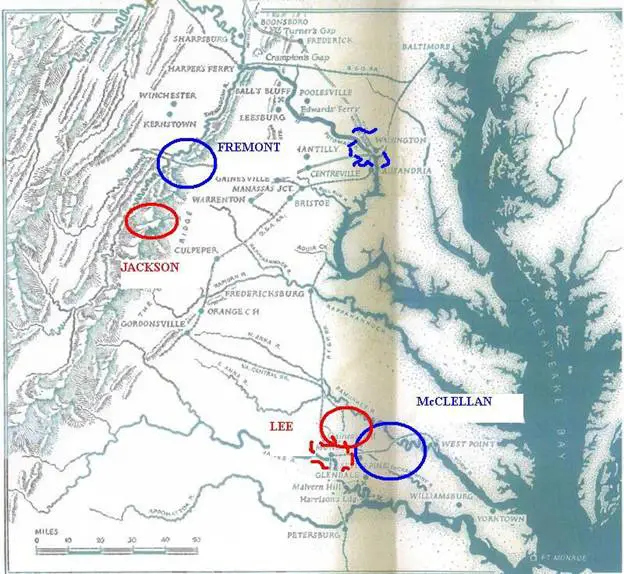

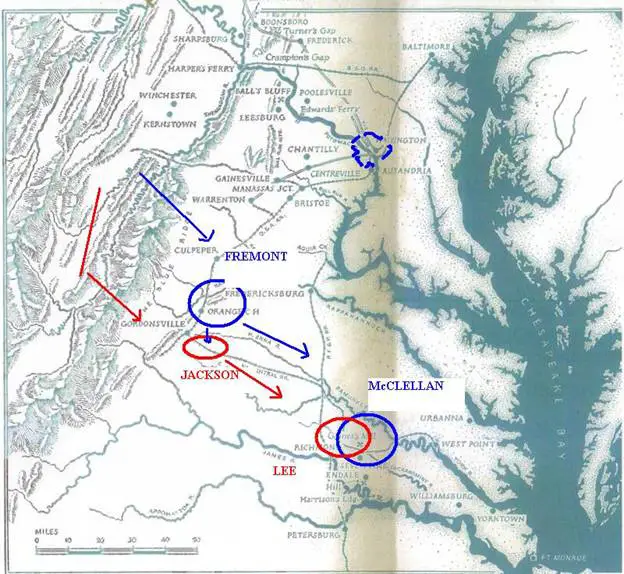

When exactly it was that Lincoln decided to hedge against the risk that McClellan's operation against Richmond might end in disaster, the evidence does not clearly show. After the fiasco of chasing Jackson through the Shenandoah Valley ended, on June 10, Lincoln did substantially reinforce McClellan, by sending to him McCall's division from Fredericksburg, and by giving McClellan control of the 14,000 drilled troops garrisoned at Fort Monroe. At the same time, though, Lincoln plainly began thinking about organizing the three corps of Fremont, Banks, and McDowell into an army for the purpose of operating independent of McClellan's control. This was the reason he called Pope to Washington and why he traveled to West Point on June 23. So, it seems reasonable to conclude Lincoln made up his mind that he would allow no more troops to come under McClellan's command during the nine days between June 14 and June 23.

Note: The only sources of eye-witness testimony as to Lincoln's state of mind during this period are the memoirs (some ghost-written) of Lincoln's cabinet ministers, Attorney General Bates, Secretary of Navy Welles, Secretary of War Stanton, and Secretary of Treasury Chase. All of these narratives are silent as to what Lincoln's intent was during this nine day period.

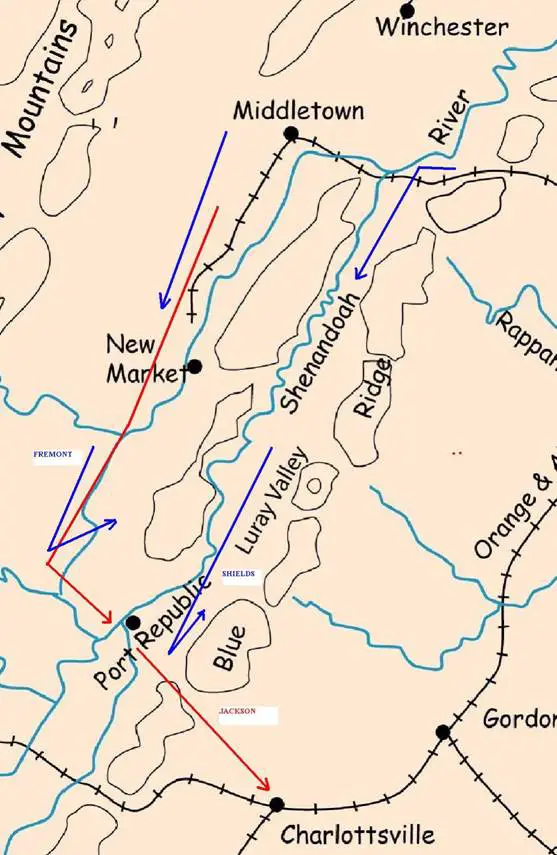

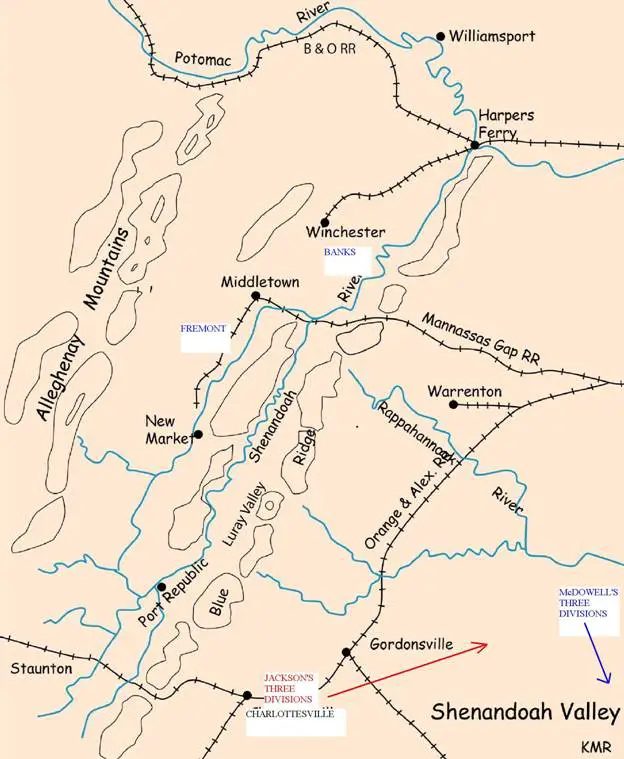

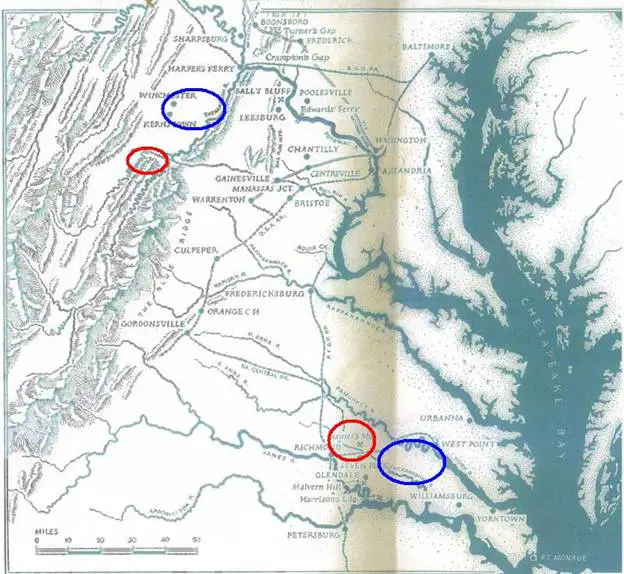

This leaves as a source only the Rebellion Record to shed light on Lincoln's thinking at this time. According to the Record, as of June 9, Lincoln's plan of operation was to have Fremont and Banks hold the line in the Shenandoah Valley and have McDowell, with three divisions―Shields, Ricketts, and King—" immediately march on Richmond to cooperate with McClellan."In order to effectuate this, Lincoln had ordered Fremont to maintain position on the valley pike, at Mount Jackson on the west side of the Massanutton Mountain, at the same time ordering Banks to relieve Shields's division, at Front Royal at the north end of the Luray Valley, so that Shields (whose brigades were scattered through the Luray Valley), could march to Fredericksburg, join up with Ricketts and King and begin marching south toward Richmond. At the same time, McCall's division was at Acquia Creek embarking for Fort Monroe.

Three days later, on June 12, the Record makes clear, Fremont and Banks were deviating from Lincoln's plan by concentrating their forces on the west side of the north fork of the Shenandoah River, on the pike between Mount Jackson and Strasburg. The news that Jackson was being reinforced from Richmond, suggested the possibility that he would again attempt to invade the lower valley and Fremont and Banks designed to meet him together at Kernstown in the southern suburbs of Winchester. This meant that McDowell had to leave Ricketts's division at Front Royal to support Shields's division that was slowly marching north through the Luray Valley in dire need of every kind of supply. In turn, then, the concentration of McDowell's corps at Fredericksburg, preparatory to marching on Richmond, was necessarily delayed.

Five Union Divisions Against the Phantom of Jackson's Three

In consequence of these developments, Lincoln, on June 12, ordered Banks to occupy Front Royal, in order that McDowell's divisions might march east of the Blue Ridge. But, on June 13, Banks responded that, for want of supplies, it was impossible for him to move from Winchester. On June 14, Banks informed McDowell that his force would not be able to move to Front Royal for "a day or two." McDowell, his headquarters then at Manassas, now ordered Shields to march, by Thornton's Gap to Warrenton, but, for want of supplies, Shields marched instead toward Front Royal, arriving there on June 16. The same day, King's division, which had been at Manassas, arrived at Fredericksburg. So, we see two things happening: first, Fremont and Banks, their forces out of supplies, are between Mount Jackson and Winchester waiting to see if Jackson reappears while McDowell is struggling to get his divisions to Fredericksburg, for the march on Richmond.

Note: On June 8, at Stanton's direction, Ambrose Burnside, commanding the North Carolina expedition, traveled to McClellan's camp on the Chickahominy. On June 12, at Lincoln's direction, he arrived in Washington and went into a private conference with the President and Stanton. On June 13, Burnside wrote a letter to McClellan disclosing his contact with Lincoln. What exactly was said in his meeting with Lincoln the evidence does not say. But, without a doubt, Lincoln certainly grilled Burnside about affairs at McClellan's front, and may have felt him out as to his willingness to step into McClellan's shoes.

On June 15, McDowell sent a personal letter to Lincoln, writing: "So much has been said about my not going to aid McClellan that I beg you will now allow me to take every man that can be spared. Jackson seems to have gone to Charlottesville, and I will have to do with him either on the way or at Richmond."(Banks at the same time as this left the valley and, at Stanton's invitation, headed to Washington to talk to Lincoln.) There is no record that Lincoln answered McDowell's letter. Three days later, on June 18, McDowell finally had Ricketts's division marching east from Front Royal, with Shields's division concentrated there and ready to follow. Banks and Fremont, still between Mount Jackson and Winchester, are fretting about reports that Jackson has returned to Harrisonburg and is heading down the pike.

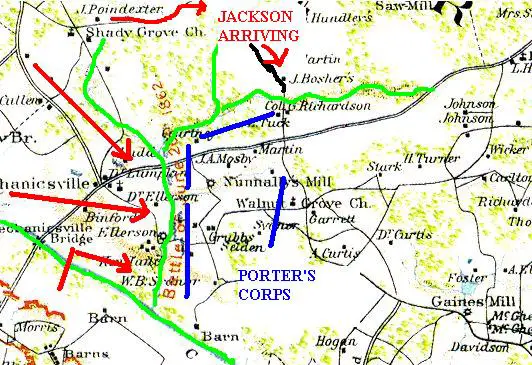

The Tactical Situation McDowell Faced, If He Marched South

The cumulative effect of the events recorded in the Rebellion Record must have led Lincoln to the turning point. The evidence shows that Lincoln's basic military policy was always based on two fundamental strategic points: first, that the war would be won by military operations in the West, not the East; second, that while the war was being won in the West, to prevent its being lost in the East, Lincoln had only to ensure that Washington was secure. Influenced by this basic mind-set, when he realized that the forces he had been personally handling were now disorganized by marching and battles, the men worn down and out of supplies, with fresh reports coming in of Jackson being reinforced and again on the offensive, he concluded it was out of the question that McDowell's force could be allowed to march to Richmond. For, it was obvious by now that somewhere along his line of march McDowell would encounter Jackson and would be drawn into a battle that would keep him from reaching McClellan.

Indeed, it must have dawned on Lincoln by this time that the Union's military operation against Richmond was an unnecessary risk to take under the circumstances of the case. What if, in the coming battle at Richmond, the Army of the Potomac was severely damaged, perhaps forced to retreat down the Yorktown Peninsula? Would not McDowell's corps be overwhelmed by the rebel army rushing on toward the Rappahannock, and what value in such circumstance would Banks and Fremont prove to be in the defense of Washington? This conclusion, in turn, must have given birth, in Lincoln's mind, to the idea of consolidating the forces of Banks, Fremont, and McDowell under one command, for the purpose of using it primarily as a blocking force against any further attempt of the enemy to "breach the line."

But under whose command? The reason, in the first place, that Lincoln had taken direct command, in March, of the individual pieces of his military forces was the problem of intractable intramural jealousies of the generals for rank, most particularly the problem of John Fremont's giant political status at that time and his total unfitness for theater command. Not trusting McClellan any longer, and thoroughly abused by Fremont's chronic insubornation, the logical first choice now was Irvin McDowell. He had previously commanded an army; though he had lost the command of it, it was because of politics, not his professional performance as a soldier. And, of all of the generals Lincoln had been dealing with for six months, McDowell had clearly been the most constant in his execution of Lincoln's orders. Furthermore, Lincoln had been using Salmon Chase as a go-between, and Chase appears to have encouraged Lincoln to adopt the new organization and put McDowell at its head.

It was Chase's idea, apparently, to use the consolidated forces to first confront Jackson and give him a battle and then operate against Richmond. As Lincoln digested Chase's idea, it was probably then that it dawned on him how he might dump McClellan and extinquish the risk he preceived existing against Washington by folding the Army of the Potomac into the army created by the consolidation of Banks's, Fremont's, and McDowell's forces.

The Military Situation Reconfigured in Lincoln's Mind

The Rebellion Record provides the tell-tale sign.

Washington, June 18, 1862

Major-General McDowell, Manassas

The President desires you would come. Be here if you can conveniently, and without danger to your command, by 9 o'clock tomorrow.

EDWIN M. STANTON, Secretary of War

Note: By this time, Lincoln has conferred with Banks and with Burnside.

Just then Irvin McDowell, a big man on a big horse, took a bad fall which resulted in an injury to his hip that put him in bed at Manassas. This fact was reported by McDowell's adjutant to Lincoln on June 19 at 8:45 a.m. Without providing any source for their statement, the historians, Benjamin P. Thomas and Harold M. Hyman, in a book titled Stanton: The Life and Times of Lincoln's Secretary of State, published in 1962, write this: "Lincoln and Stanton visited McDowell at Manassas on June 19 and 20, to seek his advice. They returned to Washington agreed that McDowell was not the man for a top command. Lincoln instructed Stanton to summon Pope to Washington." (at p. 204, edited for brevity.) And so it possibly was that Pope received a telegram from Stanton, dated June 19, ordering him to come to Washington.

Note: The Rebellion Record contradicts the statement made by Thomas and Hyman.

Washington, June 20, 1862

Col. E. Schriver, Chief of Staff (to McDowell)

Please inform me what is the condition of General McDowell this morning.

Edwin Stanton

Manassas, June 20 at 12:30 p.m.

Hon. E.M. Stanton, Washington

In reply to your telegram about General McDowell I am happy to acquaint you that he is much better this morning.

Ed. Schriver, Col., Chief of Staff

It is possible that Lincoln took a train to Manassas on the 19th and returned to Washington that night, or early in the morning hours of the 20th, but, given Stanton's message, it does not seem probable. If he had done so, he would have known what McDowell's condition was.

By June 21, McDowell was reporting to Lincoln that he was "improving and sitting up, and hope soon to regain my bodily activity." Presumably Lincoln's first choice to command the reorganized force he envisioned had been McDowell, but when on the 19th he was informed that McDowell was bed-ridden, he then decided on Pope and ordered Stanton to send Pope the telegram.

Five

days later, on June 26, McDowell was in Washington and writing this to Stanton:

"The readiest way of getting my command to join McClellan before Richmond

is to march those now at Manassas (a three day march) to Fredericksburg, there

to join King's division and thence to march (a four days' march) by way of

Bowling Green across the Mattapony and Pamunkey Rivers."This message of

McDowell's suggests that he was not seen by Lincoln at Manassas, instead as

soon as he could move, he got to Washington and pressed for authority to move

on Lincoln's existing plan. Even then it does not appear he was seen by Lincoln. Where is the President's daily diary? None apparently exists in the record.

Five

days later, on June 26, McDowell was in Washington and writing this to Stanton:

"The readiest way of getting my command to join McClellan before Richmond

is to march those now at Manassas (a three day march) to Fredericksburg, there

to join King's division and thence to march (a four days' march) by way of

Bowling Green across the Mattapony and Pamunkey Rivers."This message of

McDowell's suggests that he was not seen by Lincoln at Manassas, instead as

soon as he could move, he got to Washington and pressed for authority to move

on Lincoln's existing plan. Even then it does not appear he was seen by Lincoln. Where is the President's daily diary? None apparently exists in the record.

McDowell Would Use the Rivers to Protect His Right Flank

He received this order from Lincoln in response:

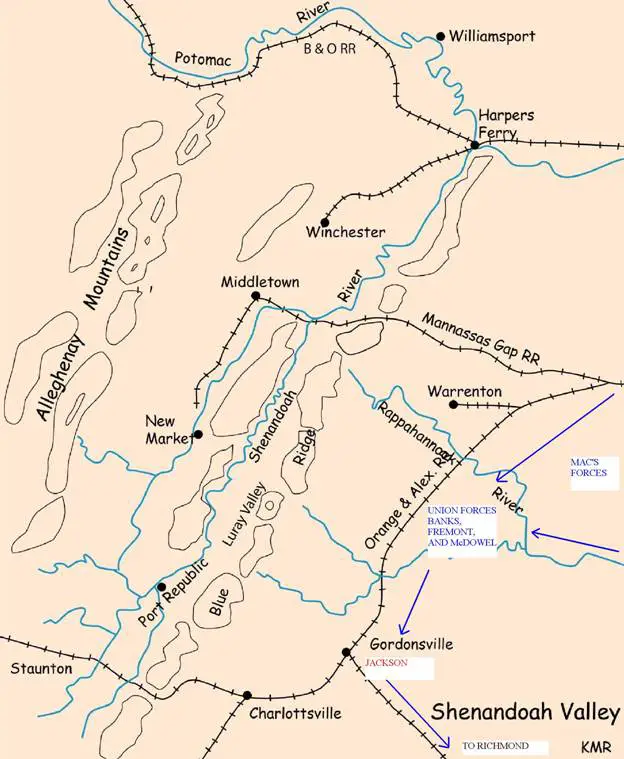

Ordered, first. The forces under Fremont, Banks, and McDowell shall be consolidated and form one army, to be called the Army of Virginia.

Second, the command of the Army of Virginia is specially assigned to Maj.Gen. John Pope, as commanding general.

Third, the Army of Virginia shall operate in such manner as, while protecting Western Virginia and the national capital from danger or insult, it shall in the speediest manner attack and overcome the forces of Stonewall Jackson, threaten the enemy in the direction of Charlottesville and render aid to relieve McClellan and capture Richmond.

Fourth, when the Army of Virginia and the Army of the Potomac shall be in a position to communicate and directly cooperate at or before Richmond the chief command shall be governed by the Rules and Articles of War.

A. LINCOLN

V

The Seven Days

|

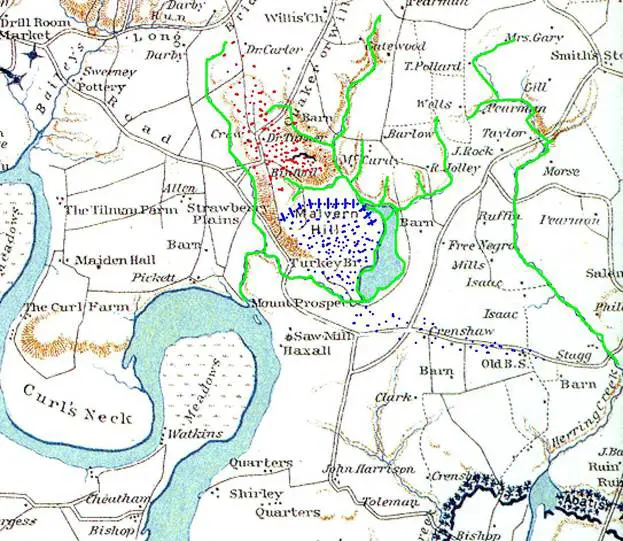

As John Pope was meeting with Lincoln on June 26, at Washington, General Lee attacked McClellan's right flank at Beaver Dam Creek, held by Fitz John Porter's corps. Six brigades, commanded by A.P. Hill, swept down the left bank of the Chickahominy in long lines; reaching the northern slope of the creek they ran down it, splashed through the water-filled bottom, under fierce artillery fire, and tried to gain the opposite crest, but, over a three hour period, were forced back by the intensity of Porter's fire. D.H. Hill's division, its first brigades getting across the Chickahominy late in the afternoon, joined the action on A.P. Hill's right and came against Porter's front at Ellerson's Mill near the mouth of the creek; entangling themselves in the abatis that skirted the place, Hill's men soon were hunkering down in the earth, making little trenches for themselves, as volleys of rifle fire from Porter's masses swept devastating sheets of lead through their ranks. But, as night fell, the advance of Stonewall Jackson's command arrived at Huntley's Corner, just beyond the extreme right of Porter's line and McClellan ordered Porter to fall back during the night to Gaines Mill. |

Unknown to Mac, Jackson's Force Arrives Totally Fagged

By morning light on the 27th, McClellan had Porter in position behind Boatswain Creek and was busy organizing the rest of his army for the march he had planned to James River, moving during the day Keyes's corps through White Oak Swamp, following with his wagon trains on a parallel road. All day Lee's forces, probably as many as fifty thousand men, threw themselves at Porter's defenses, charging time and again down into the creek bottom and up the slope trying to break into the three log-protected lines Porter had set up. Late, very late in the day, as dusk was falling, Lee finally effected a breakthrough: the 4th Texas and 18th Georgia forced a breach in Porter's center and his defenses collapsed, his men throwing down their arms and racing across the plateau that borders the stream, heading for the Chickahominy and the Grapevine Bridge.

Note: This was the great moment for Mac to have seized the day. Instead of retreating, he might have brought half, if not more, of his force on the right bank of the Chickahominy to the left, to reinforce and extend Porter's front to cover Jackson's approach. It is true, of course, that, assuming Jackson's force had stamina left, it could have kept moving to the southeast and down to the line of the York River Railroad; but Mac had the force to counter this movement. In other words he could have fought for his communications, taking the risk that he might have to retreat down the Yorktown Peninsula if his army got wrecked. This, the evidence is plain, Mac did not want to do. Whether he had good military reasons for his decision, or was motivated purely by personal interest, will always be a matter of dispute. One thing is certain: Mac did not have the force of character to compel Lincoln to keep faith in him.

|

By this time McClellan had his huge army in full motion on the right bank of the river, moving in columns on the wagon roads that threaded through White Oak Swamp. This movement forced Lee to attempt to get his forces back to the right bank, by way of Mechanicsville and McClellan's now abandoned bridges, and pursue as fast as possible; but Mac had the inside track and though Lee was able to strike his rear at several points along the march, on July 1, Mac had gotten his army safely concentrated at Malvern Hill and turned to face the enemy.

Malvern Hill

VI

The Cause of Lincoln's Failure:

He Was a Politician, Not A General

By now, it should be clear why Lincoln's military operations had failed in the East. He had wasted four months―from March 8th to June 26th, 1862—before finally taking full advantage of the Union's numerical superiority in men. In the West, the Union had over 100,000 men organized into three armies, operating against one Confederate army numbering at its height no more than 50,000. Two of the Union armies, Grant's and Pope's (soon to be Rosecrans'), held the Southern Tennessee border, threatening to move south against the Confederate army at Tupelo, Mississippi; while the third Union army, Buell's, operated eastward along the Memphis & Charleston Railroad toward Chattanooga. These three armies, operating under the command of Major-General Henry Halleck, had all but won the war in the West; though it would certainly take these armies time to get prepared to push to the heartland of the Rebellion, with Missouri, Arkansas, Kentucky, and West Tennessee solidly in Union hands, a miracle of some sort would have to happen to prevent the Confederate heartland from falling in 1863: certainly this was true if the Union's military operations in the East were to result in the capture of the Confederate Capital at Richmond.

In the East, at this time, according to the official returns, there were 203,000 men in uniform around Washington. Lincoln could have used the aggregate by dividing it three ways: Use at least one half of it to constitute the main army of operation against Richmond, and divide the other half into two pieces: one piece to man the fortications protecting Washington and the other to operate independent of, but in cooperation with, the main army.

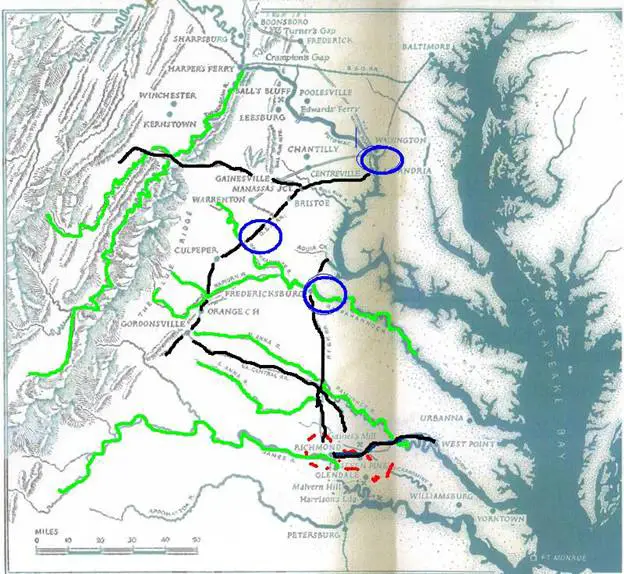

The Best Operational Advantage Comes From This Choice of Distribution

From the point of view of military science, there just can be no serious question that Lincoln would have gotten maximum advantage against the enemy, had he divided his total available force into three differently weighted pieces, and placed them, as was the situation in the West, under the supreme command of one general. Mirroring the principle of boxing―that one force is used to defend while the other force is used to strike—he could have defended Washington with one force, while the other two operated against Richmond: One of the two offensive-operating forces could have used the Orange & Alexandria Railroad as a supply line, advancing down it toward Gordonsville where it met the Virginia Central Railroad; from there this force could move along the Virginia Central toward Richmond. At the same time the main offensive army could use the Richmond & Fredericksburg Railroad as its supply line to move south toward Richmond―the two armies joining hands just north of Richmond and cooperating together in operations against it.

But this is just a paper plan, the simple drawing of three circles on the page. By March 8, 1862, Lincoln was too enveloped in the politics of the moment to act the Napoleon and enforce the organization drawn, and he had already been beaten to the idea by General Lee.

The Confederates' Strategic Situation as Early as July 1861

Between July 1861 and March 1862, a Confederate force had been operating in the Shenandoah Valley. First, under the command of Joseph Johnston, and then under Stonewall Jackson, this force moved up and down the valley, between Harrisonburg and Winchester, as the pressure applied by the countering Union force required. At the same time, a second Confederate force held a defensive position on the Manassas Plain, which was first opposed by Lincoln ninety-day men, and then, under McClellan, by his three-year men. The question is, what did Lincoln learn from it? The answer appears to be nothing. The experience should have taught him the great advantage two distinct forces (armies) have when they are operating in cooperation with each other. The Battle of Bull Run was plainly lost, because Lincoln's two armies—Patterson's in the Valley and McDowell's at Bull Run―had not cooperated and the Confederacy's had. Furthermore, all the while Lincoln was building up the three-year men into the Army of the Potomac, he was watching the confrontation going on between Patterson's army, now under the command of Nathaniel Banks, and Stonewall Jackson's. In mid-February, Banks was at Strasburg, the terminus of the Manassas Gap Railroad, having marched up the valley pike as far as Harrisonburg with Jackson retreating as he came. In March, McClellan moved his force toward Bull Run and Joe Johnston fell back to the Rappahannock. Thinking Jackson's threat to the lower valley was over, Lincoln ordered Banks to march his force east of the Blue Ridge and join McClellan's army. Immediately, Jackson marched his division rapidly down the pike and attacked Bank's right wing at Kernstown. This was the pregnant moment when the lesson of numerical advantage should have made Lincoln think of the critical edge that is given to the side which has in operation two armies cooperating. Had he learned the lesson, he would have reinforced Banks, to give him a clear numerical advantage over Jackson, and ordered Banks to keep contact with Jackson, keeping him in his front and manevuering, if not driving, him toward Richmond.

The Union's Strategic Situation in March 1862

The fact that Jackson advanced again, as soon as Banks began marching his left wing toward Fredericksburg, should have triggered in Lincoln's mind the recognition that the enemy would continue to press the Union force in the Valley whenever the numerical advantage swung in the enemy's favor; the enemy's purpose being to induce Lincoln to do exactly what he was doing—reinforcing Banks's force at the expense of McClellan's.

And that was the essential mistake Lincoln began making: reinforcing Banks's force at the expense of McClellan's. Instead of it causing Lincoln to think through how he had arranged "departments," and change that arrangement immediately, Kernstown caused Lincoln not only to order Banks to get his left wing back to the valley but also to order McDowell's corps of three divisions detached from McClellan's army.

The Strategic Situation in April 1862

Lincoln's ostensible purpose in detaching McDowell's corps was to protect Washington, but it is easy to see, when looked at in the light of military science, that Lincoln is doing the protecting the wrong way with the wrong force. If McDowell's corps had to be used independantly of McClellan's army, then it should have been absorbed into Banks's corps, or Banks's corps absorbed into it.

The Defect in McClellan's Plan Was That It Made Cooperation Difficult

In this configuration, it would have been difficult for Lincoln to reinforce McClellan by land, until such time as his valley force pushed Jackson's force toward Richmond, but Lincoln did, in fact, reinforce McClellan with Franklin's division, McCall's division, and the 14,000 drilled soldiers garrisoned at Fort Monroe. Therefore, Mac should have be able to successfully fight for his communications when Lee attacked Beaver Dam Creek. What induced Mac, as the last straw, to abandon the York River Railroad is that Jackson's force appeared on his right flank. Lincoln's organizational decisions had failed to oppose Jackson with a large enough force, in proper position for the task, which could keep in contact with Jackson, fixing him in place by pressing him aggressively all the way, if necessary to Richmond. The same thing that had happened to Lincoln at the Battle of Bull Run had happened to him again. Fool me once, . . . .

Lincoln's Organizational Decisions Made The Mess of Things

Notice the appearance of Frémont in the picture. Lincoln, from the outset, should have folded Fremont's force into Banks's, or Banks's into Fremont's, and left McDowell's corps to operate as part of McClellan's army: think of the two Union forces as Lincoln's wings. His right wing was responsible to operate against Jackson's force, keeping in contact with it and fighting it at all times. His left wing was responsible to capture the strategic point of Richmond which necessarily would be defended by the Confederates with the heaviest force they could muster.

Why didn't Lincoln do it this way? Because of the politics, plain and simple.

Remember the ranking of Lincoln's first five Regular Army major-generals? Throwing away the old men―Scott and Wool—Lincoln's list by senority of rank among the remaining three is, McClellan, first, then Frémont, and then Halleck. On March 8th, 1862, when Lincoln stripped McClellan of his role as General-in-Chief, much less on March 11th, when he turned McClellan's army into a group of corps, why didn't he either make Frémont General-in-Chief, or give Frémont command of the second force, with the mission of either destroying Jackson's force, or push it back to Richmond?

Lincoln's Top Ranking Major-Generals Cooperating in the Invasion of Virginia

How did it happen that Lee's use of Jackson's force caused Lincoln to end up with his forces strewn across the map like a child's pick-up sticks? The first cause was the political situation with John C. Frémont. This is a guy who proved as early as 1846, when he was in California, that executing orders given him by his superior was not something he was likely to do. Frémont not only refused to obey orders given him but also he invented for himself his own. When he was challenged in this, he would simply resign. He resigned from the Army in 1848, after being found guilty of insubordination, and he resigned in February 1862, after refusing to obey Lincoln's order to rescind his "Emancipation Proclamation." By March 1862, Frémont, was in Washington pressing for an army command and he was backed in his demand by a substantial part of Lincoln's party. Given the fact that he knew he could not expect Frémont to submit to authority, Lincoln, as "Commander-in-Chief" should not have given Fréemont any command, much less the command of thirty thousand soldiers, sent on a ridiculously impossible journey to capture (in Lincoln's pipe dream) the city of Knoxville, in Tennessee. Lincoln needed those 30,000 troops at hand and under the command of an army officer that could be trusted to handle them with West Point professionalism, cooperating with his counterpart, McClellan: both of them protecting Washington by pressing the enemy back to Richmond. Irvin McDowell was the obvious choice to do this, yet Lincoln allowed Frémont's crowd to force him to create the "Mountain Department."

How do the historians explain this? Here are some pathetic examples.

"The `Quaker gun' affair, as the stage prop guns were called, provoked the wrath of the radicals. `We shall be the scorn of the world,' Senator Fessenden wrote his wife. `It is no longer doubtful that General McClellan is utterly unfit for his position. . . and yet the President will keep him in command.' Echoing Fessenden's dismay, the Committee on the Conduct of the War demanded McClellan's resignation. When Lincoln asked who they proposed to replace McClellan, one of the committee members growled, `Anybody.' Lincoln's reply was swift. "I must have somebody.'

Lincoln was convinced that something had to be done. On March 11, he issued a war order that relieved McClellan from his post as general in chief but left him in charge of the Army of the Potomac. Lincoln gave Halleck command [in the West], and, in a move that delighted the Radicals, reinstated Frémont to take charge of the newly created Mountain Department. The post of general in chief was not filled, leaving Lincoln. . . to determine overall strategy." (Team of Rivals [2005], at p. 428, written by the prize-winning historian, Doris Kearns Goodwin.)

Note: That's it? One line and Frémont sails into the slot of commanding 30,000 men on a mission to nowhere, that takes them entirely out of position to suppress Jackson's force operating in the valley. Why Lincoln, at the same time he made his third-highest ranking general commander of all forces in the West, did not make his second highest ranking general commander of all forces in the East, not operating as part of McClellan's army, Ms. Goodwin provides no insight.

"The self-willed Frémont had been placed in command in West Virginia; Banks, a Massachusetts politician of unproved military competence, was at or near Strasburg in the Valley; McDowell's corps was still on the Rappahannock at Fredericksburg. Should these forces be thrown against Jackson; and, if so, how and where?" (Abraham Lincoln, a Biography [1968], at p. 238, written by the prize-winning historian, Benjamin P. Thomas.)

Note: Frémont was not "placed in command in West Virginia." He was placed in command of the "Mountain Department" which extended through the Appalachian Mountains, from the Potomac River to Knoxville. Only as he was marching south through the narrow mountain valleys, did Lincoln call for him to march east to Harrisonburg and block Jackson's line of retreat on the valley pike; an order Frémont chose to ignore. Why did Lincoln not give Frémont command of all the troops north of the Rappahannock, and why send him far away with so many men at such a time as this? Mr. Thomas does not explain.

"In the spring of 1862 Lincoln created the Mountain Department, in what would become West Virginia, to provide Frémont a new command and a second chance. The result was another Frémont failure once Stonewall Jackson moved into the Shenandoah, but Lincoln could live with that. If he had not put the Pathfinder in a command where his supporters could be temporarily appeased and any defeat absorbed, he would have come under possibly irresistible pressure to give the Army of the Potomac to Frémont, a man capable of engineering a truly irreparable disaster, the kind that might have ruined all chances of winning the war." (Lincoln's War: The Untold Story of America's Greatest President as Commander-in-Chief [2004], at p. 330, written by the award-winning author, Geoffrey Perret.)

Note: Having dumped Frémont once, why did Lincoln give "a man capable of engineering a truly irreparable disaster, the kind that might have ruined all chances of winning the war," another chance to do exactly that? Why did Lincoln have to "appease" Frémont's supporters? Who exactly were Frémont's "supporters?"Mr. Perret does not say.

"The order of March 11. . . created the Mountain Department, the command of which Lincoln gave to General Frémont, whose reinstatement had been loudly clamored for by many prominent and enthusiastic followers. . . . Rationally considered, [Jackson's valley campaign] was an imprudent and even reckless adventure that courted and would have resulted in destruction or capture had the junction of forces under McDowell, Shields, and Frémont, ordered by President Lincoln, not been thwarted by the mistake and delay of Frémont. It was an episode that signally demonstrated the wisdom of the President in having retained McDowell's corps for the protection of the national capital." (Abraham Lincoln: A history [1902], at p. 300, by John G. Nicolay)

Note: Frémont's "prominent followers" were many of the Radical Republicans, men like Sumner, Wade, Chandler, and Stevens. Frémont ran as a third party candidate, in 1864, promoted by the Radicals. He dropped the campaign in September 1864 and finally disappeared from view. Jackson's capture or destruction was not thwarted by Frémont's "mistake and delay," but from the simple reality that the Union forces Lincoln pushed at him, could not reach strasburg before he could. Lincoln's order to Frémont, to move east to Harrisonburg, to block Jackson's retreat up the pike, was quite properly ignored by Frémont, as it put Frémont's column in a position from which it could not be supplied. Frémont moved quickly enough north to Moorfield, a supply depot, and from there moved east toward Strasburg while Shields's division moved west toward that point. Jackson got there first.

"Shields pushed forward to Front Royal, which place he reached on Friday. McDowell followed, reaching that place on Saturday. The object was to cut off the retreat of Jackson through Front Royal. Meantime Frémont, observing the spirit though not the letter of his orders, had marched to Moorfield and thence to Wardensville a few miles distant from Strasburg—his directions being to occupy Strasburg and cut off the retreat of Jackson by that road. Unfortunately Frémont did not reach Strasburg until Jackson had passed through Strasburg, on his retreat down the valley." (Inside Lincoln's Cabinet: The Civil War Diaries of Salmon P. Chase)

Note: Chase's "diary," as with Welles's and Bates, tells us nothing about what happened among the principal players that resulted in Lincoln appointing Frémont a department commander.

Frémont's most important biographer, the prize-winning Allan Nevins, wrote this: "There ensued an immediate explosion in Congress. Frank Blair, on March 7th, made a vitriolic speech attacking Frémont's Missouri record, and the Congressional radicals rushed to the fray. The leading address in Frémont's behalf, delivered by Schuyler Colfax, was a masterly presentation of his case. Lincoln saw that it was best to yield to the storm, and give Frémont another opportunity in the field. The general was immediately assigned to head the newly created Mountain Department which comprised western Virginia, eastern Kentucky, and a part of Tennessee. Proceeding with his wife and two children to Wheeling, Frémont there relieved Rosecrans on March 29, 1862. . . . Though his force was small, amounting to about 25,000 men on paper, and actually to much less (Lincoln says he gave him 30,000 men), his Department represented a pet idea of the President's. (Lincoln could hardly afford at this time "pet ideas.") Lincoln believed it feasible to march from western Virginia over the mountains into East Tennessee and seize the railroad at Knoxville. This would have been impossible even for a much larger force. Yet Frémont was put in a position where he had to promise to attempt the feat." (Frémont: Pathfinder of the West, [1992]at pp. 554-555.)

Note: Nevins gives us no insight into what facts he was relying on for his narrative, "Lincoln saw that it was best to yield. . . and give Frémont another opportunity in the field." Nor does he offer an intelligent explanation why Lincoln would have "believed" such a stupid thing as Fremont marching over 400 miles through mountains to Knoxville. You students who want to investigate the facts, the work, I admit is hard; you must drill into the original manuscripts of the players that exist in the Library of Congress, and find the facts. What exactly was the nature of the "storm" Nevins points to, and exactly how did it force Lincoln to (1) appoint Frémont to a command in the East, and (2) give him 30,000 men to use in a senseless endeavor, when they were so desperately needed for a much more important purpose—upon which the success of Lincoln's whole military operations in the East depended? Good luck, it is an unexplored hole.

Too late to save the Union's military campaign, Lincoln woke up to the fact that he had been misusing his numerical advantage, induced by his efforts to cope with Republican politics. On June 26, as the Battle of Gaines Mills was raging, and after dancing the flamenco in public, he finally orders all the troops he has, not attached to McClellan's army, to concentrate together as the "Army of Virginia" and he pulls John Pope from the West to command it.

Lincoln Blunders

Having finally gotten it right with his right hand, Lincoln now gets it wrong with his left hand; he orders McClellan to move the Army of the Potomac back to the Manassas Plain, thereby guaranteeing that the combined forces commanded by Lee and Jackson will be free to attack and destroy the Army of Virginia. Had Lincoln left Mac where he was, at Harrison's Landing, the Army of Virginia would have been able to come down the Orange & Alexandria Railroad to Gordonsville, unopposed by a rebel force of sufficient numbers to prevent it. This would, of course, depend upon Mac moving toward Richmond again; putting enough pressure on Lee to induce him to use his force to defend the place. But then Lincoln did not trust McClellan to do this. And, it must be admitted, he certainly had good reason not to.

The Politics of Army Command was Just Too Much For Lincoln To Control

So he should have replaced him with someone he did trust; someone like Burnside, ordering him to take command of McClellan's army whether he liked it or not; or ordering Fitz John Porter to take the command, if Burnside would not; or ordering Sumner to do it; or ordering McDowell to do it. Ordering somebody! Lincoln had his gnarled hands tight around the Confederacy's throat; to release the pressure and back away is just incomprehensible, indefensible from a strictly military point of view. But then Lincoln was not a general. He was a politician and it was the politics of the moment that Lincoln could not contain.

Why didn't Lincoln think of Grant? Was it that Grant was too far away, too obscure, too controversial himself? Just too early for anyone to recognize Grant was the man.

Joe Ryan

What Happened in June 1862

In The House of Representatives

The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant June 1862

The War In The East

| Read all the Civil War Sesquicentennial articles | Comments and Questions to the Author |

|

Joe Ryan Original Works @ AmericanCivilWar.com Joe Ryan Video Battlewalks |

|

| About the author: Joe Ryan is a Los Angeles trial lawyer who has traveled the route of the Army of Northern Virginia, from Richmond to Gettysburg, several times. |

||

Battle of Gettysburg

General Robert E. Lee

General JEB Stuart

General Jubal Early

Confederate Commanders

General Joseph Hooker

Union Generals

American Civil War Exhibits

State Battle Maps

Civil War Timeline

Women in the Civil War