| Read all the Civil War Sesquicentennial articles | Comments and Questions to the Author |

The War in the East

I

| General McClellan Progression |

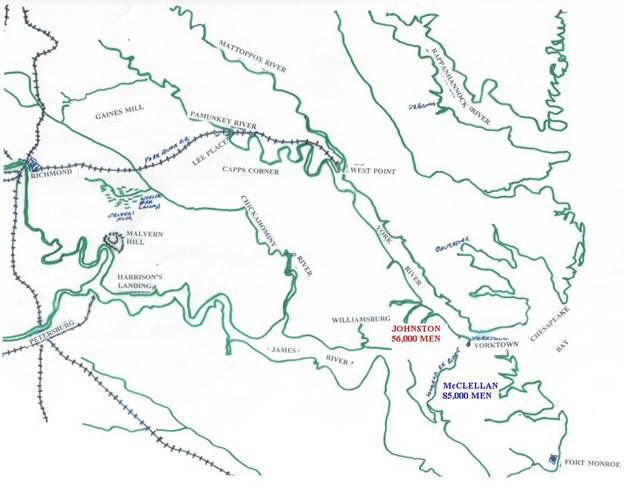

McClellan's Army Moves Toward Yorktown

On the afternoon of April 2, 1862, George McClellan arrived on board the steamer, Commodore, at Hampton Roads. By this time, using almost 400 vessels, McClellan had moved to the tip of the Yorktown Peninsula, almost 60,000 men, 15,000 animals, 1,200 wagons and ambulances, 44 artillery batteries and many tons of ancillary supplies. (Using the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers, Henry Halleck, in the West, had just done essentially the same thing.) Following eventually, came the two divisions of Sumner's corps and William Franklin's division, detached from McDowell's corps.

Two days later, with Navy gunboats steaming up the York River to shell the rebel batteries at Yorktown, McClellan's march to Yorktown began, with two columns marching on parallel roads: Samuel Heintzelman's two divisions marched from Newport News on the main road to Yorktown while Erasmus Keyes, General Scott's old military secretary, moved his two divisions on a branch road on the James River side of the Peninsula. Behind these lead divisions would come the rest of Mac's army, followed by immense artillery and supply trains.

The Army of the Potomac Begins to March

No sooner had McClellan's march up the Peninsula begun than a disheartening communication came to him from the War Department, the consequence of which would eventually prove to be the wreck of the campaign.

ADJUTANT GENERAL'S OFFICE, April 4, 1862

General McClellan:

By direction of the President, General McDowell's army corps has been detached from the forces under your immediate command, and the general is ordered to report to the Secretary of War.

Lorenzo Thomas, Adjutant General

In 1864, publishing to the public his report of the Richmond Campaign, McClellan wrote vehemently about this.

"I was shocked at this order, which with that of March 31 (removing Blenker's division from me), removed nearly 60,000 men from my command, and reduced my force by more than one third after its task had been assigned, its operations planned, its marching begun. To me the blow was most discouraging. It frustrated all my plans for impending operations. It fell when I was too deeply committed to withdraw. It left me incapable of continuing operations which had been begun. It compelled the adoption of another, a different, and a less effective plan of campaign. It made rapid and brilliant operations impossible. It was a fatal error."

Note: Mac had originally planned on landing a force on the lower Rappahannock and marching it to Gloucester Point, opposite Yorktown, seize the batteries at that place and then move the force directly to West Point, thus turning the Yorktown fortified lines.

McClellan replied to the War Department's order with a telegram sent to Lorenzo Thomas, the evening of April 5.

HEADQUARTERS, ARMY OF THE POTOMAC

CAMP NEAR YORKTOWN, April 5, 1862

Brig. Gen. Thomas, Adj. Gen. U.S.A.

General:

The present state of affairs renders it exceedingly unfortunate that McDowell's corps has been detached from my command. It is no longer in my power to move directly upon West Point. I am reduced to a frontal attack upon a very strong line at Yorktown. Without McDowell's corps I do not think I have sufficient force to accomplish the object of this campaign with that certainty, rapidity, and completeness which I had hoped to obtain. I hope it will be realized that more caution on my part will be needed, after having been deprived of such a very large force at a time when I am under fire.

Your obedient servant, General B. McClellan

Maj.Gen. Commanding

To this, Mac received two days later this brusk and really incomprehensible response from Lincoln.

WASHINGTON, April 6, 1862

Gen. G..B. McClellan:

You now have over one hundred thousand troops with you. I think you had better break the enemy's line from Yorktown to Warwick River at once.

A. Lincoln. President

|

What Lincoln was thinking when he wrote this defies imagination. At the time he wrote it, Henry Halleck in the West had about 40,000 men concentrated on the west bank of the Tennessee River at Pittsburg Landing,, with many more regiments on transports heading there from Cairo. He also had Buell's army of about 50,000 marching there from the east. Once all these western troops were concentrated at Pittsburg Landing, Halleck meant to move the whole force through twenty miles of forest and attack the railroad crossroads at Corinth, Mississippi, meeting at some point, and probably defeating, the smaller rebel army in his front. Halleck received no "you better strike the enemy at once" messages from Lincoln. |

To his wife, Mary Ellen, Mac wrote this on April 6th.

Near Yorktown, April 6, 1862

Dear Wife,

Fitz John Porter is in the advance on the right, finding the enemy in strong force in a very strong position; and Baldy Smith is on the left. Thus far it is altogether an artillery affair. While listening to the guns this afternoon, I received the order detaching McDowell's corps from my command—it is the most infamous thing that history (so far) has recorded. The idea of depriving a general of 35,000 troops when actually under fire?

Your husband, George

It took Henry Halleck thirty days to move his army the twenty miles between the two points. Yet, Lincoln wrote Halleck no nasty notes, nor did he interfere in any way with Halleck's plans. But, no sooner had McClellan begun to move toward Richmond than Lincoln not only substantially interfered with Mac's plans but is demanding that Mac order the troops he has available (about 50,000) to immediately make a frontal attack against a fortified line.

What was the tactical basis for Lincoln demanding McClellan make a frontal attack immediately upon arriving in front of Yorktown? Lincoln had no knowledge of the conditions that existed at that time. He had no previous experience with masses of troops making frontal assaults on entrenched positions. The conclusion follows from this that Lincoln's mindset was for McClellan to ignore the amount of casualties that troops can be expected to suffer in making a frontal attack against a fortified position that is completely intact and defended by scores of artillery batteries.

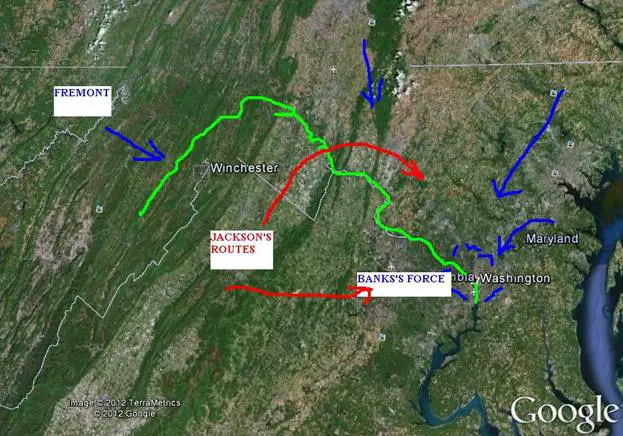

Washington Fortifications

What was the strategic necessity that justified Lincoln's demand that McClellan make such an attack immediately? Was Washington in danger? Hardly, for at this time, by Lincoln's interference with Mac's plans, there were more men protecting Washington, tactically as well as strategically, than McClellan had with him on the Peninsula. Lincoln now has established separate "departments" stretching from Wheeling, West Virginia, to Washington: Fremont with 20,000 men is in the Appalachians; Banks with 20,000 in the Shenandoah Valley chasing down Jackson; McDowell, with 35,000 to 40,000 men, is at Fredericksburg; there is a garrison of 18,000 men in the forts around Washington. The only rational explanation for Lincoln's conduct is that his motive, in taking control of a total force of almost a hundred thousand men, was to hold territory, not to defend Washington.

Lincoln's Chain of Command At This Time |

||||||||||||||

| Lincoln―(Board

of Advisors) Stanton |

||||||||||||||

|

It is true, of course, that Stonewall Jackson, with one division of infantry, was in the Shenandoah Valley, but, regardless of his ability to march men toward the Potomac, the idea that his force posed an actual threat to Washington is ridiculous. Assuming no resistance, Jackson, who at this time has about 9,000 men, might have attempted to march down to the Potomac at Harper's Ferry, cross over at that point into Maryland. . . and then what? He would have to march east fifty miles, passing Frederick, Urbanna, and Gaithersburg, at which point he would arrive in front of the forts garrisoned by about 20,000 men. Alternatively, he might have attempted to march across the Blue Ridge Mountains, at, say, Sperryville or Front Royal, join with Ewell's division at Gordonsville, cross fifty miles of the Manassas Plain, where he would arrive in front of the Washington forts with still a river to cross, and at a point where it could not be done without a bridge.

The Idea that Jackson Might March to Washington Too Ridiculous to Consider

The march would take Jackson at least ten days to accomplish. During this time, what is happening? Nothing? Of course not. Lincoln and his crowd would be calling on General Dix, commanding the Department of Baltimore, to send troops by train to Washington and they would be calling on General Wool, commanding the Department of Pennsylvania, to send troops by train to Washington. At the same time, presumably, Nathaniel Banks, holding the line Winchester-Front Royal-Warrenton-Manassas with 20,000 men, would be concentrating to block Jackson's march at some point. Certainly, during this time, Fremont's force of 20,000 men would be ordered to move against Jackson's line of retreat. Jackson would need a great many more troops that he was known to have, to attempt such an incredible endeavor.

But, Lincoln might argue: there is an enemy force spread along the Rappahannock, from the vicinity of Gordonsville to Fredericksburg. This force might advance directly north across the Manassas Plain, as Jackson marched down the Valley or crossed the Blue Ridge.

All right, this was possible but was it reasonably

probable? Union reconnaissance made it clear at the time that there were two

rebel divisions―one at Gordonsville and one at Fredericksburg―which

could possibly move toward Washington. Thus, if it materialized, the feared enemy

attack on Washington would be composed, at a maximum, of three divisions, say

about 25,000 to 30,000 men. In an abundance of caution, certainly justified if

there were any reasonable chance Washington might be suddenly taken, a

reasonable person in Lincoln's shoes might well have held one of

McDowell's four divisions at Fredericksburg, but to hold back McDowell's entire

corps from McClellan clearly cannot be justified on the ground of protecting

Washington. No, a reasonable person, if all he cared about was protecting

Washington while the siege of Richmond went on, would have used Blenker's

division instead, or for that matter, Fremont's entire force, to cooperate with

Banks's force in protecting the place.

All right, this was possible but was it reasonably

probable? Union reconnaissance made it clear at the time that there were two

rebel divisions―one at Gordonsville and one at Fredericksburg―which

could possibly move toward Washington. Thus, if it materialized, the feared enemy

attack on Washington would be composed, at a maximum, of three divisions, say

about 25,000 to 30,000 men. In an abundance of caution, certainly justified if

there were any reasonable chance Washington might be suddenly taken, a

reasonable person in Lincoln's shoes might well have held one of

McDowell's four divisions at Fredericksburg, but to hold back McDowell's entire

corps from McClellan clearly cannot be justified on the ground of protecting

Washington. No, a reasonable person, if all he cared about was protecting

Washington while the siege of Richmond went on, would have used Blenker's

division instead, or for that matter, Fremont's entire force, to cooperate with

Banks's force in protecting the place.

Union Gun In Washington Defenses |

If we are to treat Lincoln in this as acting as a reasonable person, then the only explanation for his conduct, is that he wanted everything—he wanted to use Fremont to hold territory and therefore stripped McDowell's corps from McClellan's army to guarantee absolute protection for Washington. His conduct was cavalier and short-sighted; in the end, in conjunction with McClellan's failure as a general, it would bring ruin to the great Union operation against Richmond and cause the war in Virginia to go on two years longer.

In the panic that overcame him, in June when General Lee attacked McClellan's flank and rear, Lincoln sent a flood of telegrams to Henry Halleck, in the West, imploring him to send east by train, 50,000 men. Halleck responded by claiming offensive operations would have to cease in the West if this was done. Lincoln lowered his demand to 25,000, but on this condition only―"Please do not send a man if it endangers any place you deem important to hold or if it forces you to delay the expedition against Chattanooga. To take and hold the railroad at or east of Cleveland, in East Tennessee, I think fully as important as the taking and holding of Richmond." Really?

Cutting off Chattanooga's communications with Knoxville

"as important" as capturing Richmond?

Certainly, capturing Chattanooga was at that time "as important" as capturing Richmond, but the question was, which general, in April 1862, had a better chance of capturing one place or the other. Certainly the answer is not, Henry Halleck. Halleck arrived at Pittsburg Landing on April 14, to find that Grant's Army of the Tennessee was in a shattered condition. He could not begin the campaign to capture Chattanooga, much less the railroad east of that place, until he had reorganized Grant's army and brought Pope's Army of the Mississippi to Pittsburg Landing. He then had to advance to Corinth, attack or maneuver the enemy out of that place and then. . . ? And then he had to consolidate his hold on the vast territory that his operations to that point had gained for the Union.

First, he had to deploy his troops to repair the railroads that now necessarily, with the fall of water level in the Tennessee, had to function as his lines of communication with his base of operations at Cairo, Illinois—a distance of 175 miles.

Second, he had to deploy his troops to occupy two major rebel cities, Memphis and Nashville, not to mention the many key points on the railroads in between that required protection.

Third, he had to deploy his troops in a manner calculated to suppress the burgeoning guerilla warfare that now sprang up all around him while keeping Beauregard's army at bay. In doing all this, Halleck was clearly of the view that offensive operations in his department, which now stretched from Kansas to Fremont's "Mountain Department," some four hundred miles as the crow flies, had come to an end for the spring and summer at least.

As for Lincoln's thinking that there was any reasonable chance Halleck would capture Chattanooga, much less Cleveland, it had no rational foundation in fact? And this is a trial lawyer who supposedly won more cases than he lost, convincing juries his were the better cause.

After the capture of Corinth, Halleck did send Carlos Buell's army off on the mission of "capturing" Chattanooga, but he knew nothing would come of the effort until the fall, because he ordered Buell to move by the Charleston & Memphis Railroad instead of by the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad. By the Charleston & Memphis Railroad Buell had to march 250 miles over a road that could not be used to support him logistically, until the several major bridges it traversed were rebuilt and locomotives and boxcars put on it. Buell would have to do this by guarding every mile of track from the guerilla bands infesting the captured territory. This would take much time, guaranteeing that Buell would not see the church spires of Chattanooga any time soon.

It is just impossible to believe Lincoln seriously thought that Halleck could do more, in capturing territory from the enemy, than he had already done. Halleck had achieved a great result in the West, and after a time he would be able to leap forward to Chattanooga, but not now. This was the time for Lincoln to concentrate his attention on supporting McClellan, as he had supported Halleck, giving McClellan the best chance possible to achieve an equivalent result for the Union in the East by giving him the most men possible.

The Yorktown Terrain and Defenses

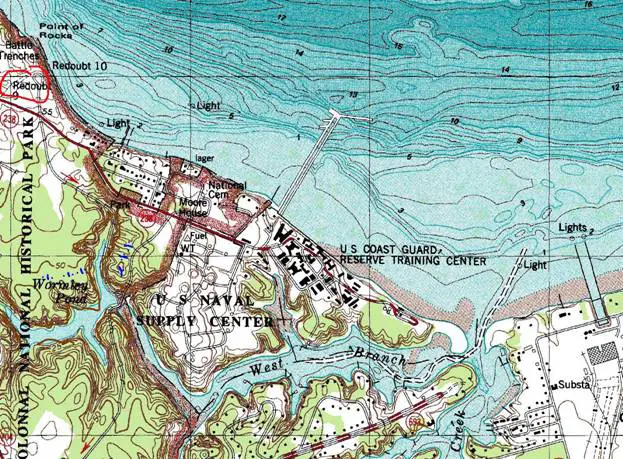

Yorktown Defenses, entrenchments, artillery, and water obstacles

McClellan's Lines Inch Up To The Enemy's

McClellan's Key Artillery Positions

On April 9th, apparently stung by McClellan's reaction to his conduct, Lincoln wrote a very long letter to McClellan attempting to explain himself.

Washington, April 9, 1862

Major General McClellan:

My Dear Sir, your dispatches pain me very much. Blenker's division was withdrawn because of the political pressure put to me. As to the rest, when I found out you left me less than 20,000 unorganized men, without a single field battery and Banks was tied up in the Valley with Jackson and could not leave without exposing the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad I was constrained to substitute something for him myself. Do you really think I should permit the line from Richmond via Manassas to Washington to be entirely open, except what resistance could be presented by less than 20,000 unorganized troops?

I think it is the time for you to strike a blow. And let me tell you, it is indispensable to you that you strike a blow. The country will not fail to note that the present hesitation to move upon an entrenched enemy, is but the old story of Manassas repeated. You must act.

Yours, very truly, A. Lincoln (edited for brevity)

Lincoln writes this three days after the battle of Shiloh occurred, rendering for the Union over 13,000 casualties and wrecking Grant's army, and the battle occurring without fortifications involved. Just amazing!

|

If Lincoln wished his field general to be as bold as Grant was in the forest of Shiloh, he should have steamed down to Fort Monroe, mounted a horse and rode to the front, to judge with his eyes how formidable was the physical character of the enemy's entrenchments and the depth, density and placement of their artillery. A field general's choice in the situation confronting McClellan was to either attempt a frontal assault against the fortified position in his front, or first reduce the effectiveness of the enemy's position by the regular operations of a siege. That McClellan, despite Lincoln's preemptory demand for "Charge em out!", did what Halleck did at Corinth is a testament to his West Point professionalism. And all the chanting of the historians and civil war writers that Mac had "the slows," as Lincoln is supposed to have said, demonstrates their naiveté. |

Mac replied to Lincoln on April 20 with this:

Headquarters, Army of the Potomac, April 20

His Excellency The President

My Dear Sir. I enclose a map of the vicinity, to give you a good idea of positions. We are at work building enclosures for six batteries, plus ten 13-inch mortars. As soon as these are armed we will open the first parallel and other batteries for 8-inch and 10-inch mortars and other heavy guns. We shall soon open with a terrific fire. The difficulties of our position are considerable, that is the enemy is in a very strong position, but I never expected to get to Richmond without a hard fought battle and am willing to fight it here as anywhere.

I am, Sir, most respectfully and sincerely your friend,

Geo B. McClellan

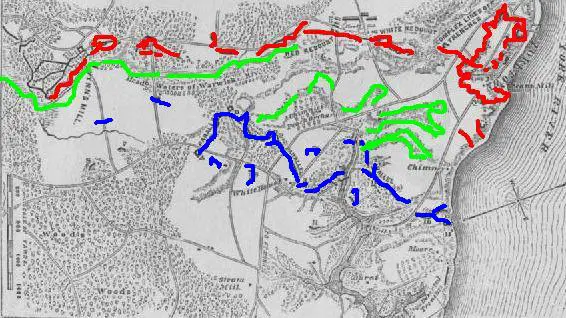

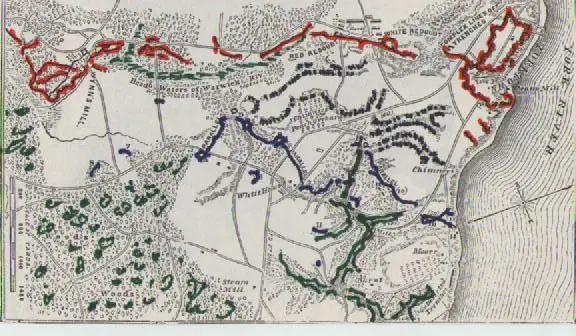

By the end of April, McClellan's army had moved by traverses and parallel trenches to within a hundred yards of the enemy's line of entrenchments, this done under a constant artillery barrage. He now had in place, in counter battery, five 100 pounder Parrott guns, ten 4-inch ordnance guns, eighteen 20 pounder Parrotts, six Napoleons, six 10 pounder Parrotts and forty-five other guns of smaller caliber, in redoubts.

Sally Gate in Confederates Entrenchments at Yorktown

McClellan's siege works at Yorktown

Lincoln answered this with, "Is anything to be done?" Lincoln wrote this as Halleck was still sitting at Pittsburg Landing, not having started on the twenty mile march that would bring him to lay siege to Corinth―a siege that would see Halleck do in front of Corinth exactly what McClellan was doing in front of Yorktown, and there is no evidence in the record of Lincoln dissing him. What explains Lincoln's contradictory treatment of these generals the record does not say.

II

The Confederates Scramble to Defend Richmond

Confederate Divisions In Northern Virginia

Confederate Force Confronting McClellan at Yorktown

As it was in the West, it was the same in the East. The Confederate Government did not have available a force equal in size to that available to Lincoln's Government. Compounding the Confederates' disadvantage was the fact that they lacked rifles so that a significant portion of their men could not be immediately armed. This problem was diminishing as privateers, operating out of the Bahamas, began to arrive in Southern ports carrying cargoes of arms and munitions and universal conscription became the law, but right now, and for several months to come, the problem of shortage would remain acute.

Joe Johnston, in field command of the Confederate Army in Virginia, arrived at Yorktown at about the same time McClellan's forces began moving up the Peninsula from Fort Monroe. At the time of his arrival there were present about 25,000 Confederate troops. Half of them were manning the entrenchments at Yorktown, under the command of John Magruder; the other half, under the command of Benjamin Huger, were holding the navy yards at Norfolk. Johnston brought with him about 25,000 men, organized in three divisions under the command of James Longstreet, D.H. Hill, and D.R. Jones.

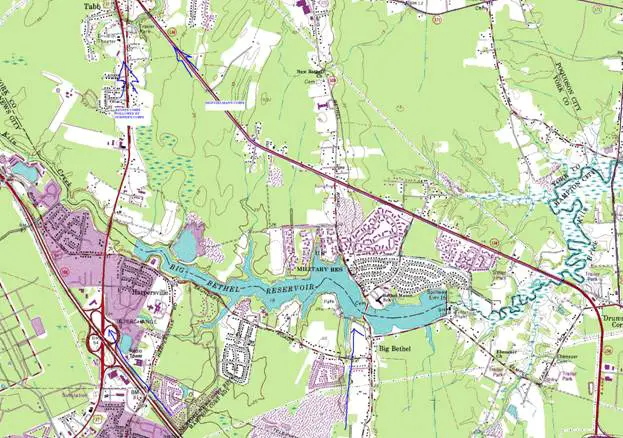

Joe Johnston found a fourteen mile long string of defenses,

stretching across the Peninsula from the mouth of the Warwick River to where it rises near the town of Yorktown. From in front of Yorktown to the bank of the

York River there are a series of deep water filled ravines that make the

movement of massed infantry impossible without the construction of roads and

causeways. Magruder had dammed the stream in different places to create large

pools of water and, on the high ground overlooking the stream, he had built a

line of field works directly on top of the old revoluntary field works of 1778.

At Yorktown as well as Gloucester Point, batteries were in place, their field

of fire interlocked to prevent Union vessels from steaming past the town.

Joe Johnston found a fourteen mile long string of defenses,

stretching across the Peninsula from the mouth of the Warwick River to where it rises near the town of Yorktown. From in front of Yorktown to the bank of the

York River there are a series of deep water filled ravines that make the

movement of massed infantry impossible without the construction of roads and

causeways. Magruder had dammed the stream in different places to create large

pools of water and, on the high ground overlooking the stream, he had built a

line of field works directly on top of the old revoluntary field works of 1778.

At Yorktown as well as Gloucester Point, batteries were in place, their field

of fire interlocked to prevent Union vessels from steaming past the town.

Johnston recognized that the fortified line was a substantial obstacle to McClellan's advance and thought that it could be defended for a very long time, but for the fact that it could be easily turned if the enemy could use either James River or York River to get troops in the rear of it. At the moment, the rebel ironclad, Virginia, blocked the mouth of James River and the field and water batteries were holding the enemy back on the York River, but this situation could change very quickly; if it did, the Confederate troops would have to scramble to get closer to Richmond before McClellan could throw an infantry force in his rear, of sufficient force to block his retreat.

On April 14, bringing with him James Longstreet, Johnston appeared in Richmond and went into a meeting with President Davis, Secretary of War Randolph and the general commanding Confederate forces, Robert E. Lee. Johnston expressed the attitude that, while the Yorktown defenses were strong and would force the enemy to spend weeks laying siege to the place, it would be eventually turned by the enemy opening the York River by demolishing the water batteries and getting troops past it by water. Instead of engaging the enemy in a delaying action, Johnston pushed the proposition of concentrating as much force as possible in front of Richmond and attacking McClellan as he came up.

General Lee came to the meeting with a full understanding of the

strategic situation confronting the Confederacy. In the West, the Confederate

army was standing on the defensive at Tupelo, Mississippi, about 30 miles south

of Corinth on the Mobile & Ohio Railroad waiting to see what Halleck's

armies would do next. Anticipating that Halleck would now go over to the defensive,

in order to consolidate his gains in territory, Lee had managed to cobble

together a force of 12,000 men, under the command of Kirby Smith, and had him

in motion toward Knoxville and the Cumberland Gap, with instructions that he

hold himself ready "for rapid movements whenever the enemy may expose

himself to a blow." In the East, Fremont had two columns in motion in the Alleghenies,

moving south toward Moorfield, and Stonewall Jackson, in the Shenandoah Valley,

was retreating toward Harrisonburg, pursued by Banks. Here, too, Lee,

anticipating an opportunity to seize the initiative, had sent instructions to

Richard Ewell, posted near Gordonsville, to move part of his division toward

Swift Run Gap in the Blue Ridge, to connect with Jackson.

General Lee came to the meeting with a full understanding of the

strategic situation confronting the Confederacy. In the West, the Confederate

army was standing on the defensive at Tupelo, Mississippi, about 30 miles south

of Corinth on the Mobile & Ohio Railroad waiting to see what Halleck's

armies would do next. Anticipating that Halleck would now go over to the defensive,

in order to consolidate his gains in territory, Lee had managed to cobble

together a force of 12,000 men, under the command of Kirby Smith, and had him

in motion toward Knoxville and the Cumberland Gap, with instructions that he

hold himself ready "for rapid movements whenever the enemy may expose

himself to a blow." In the East, Fremont had two columns in motion in the Alleghenies,

moving south toward Moorfield, and Stonewall Jackson, in the Shenandoah Valley,

was retreating toward Harrisonburg, pursued by Banks. Here, too, Lee,

anticipating an opportunity to seize the initiative, had sent instructions to

Richard Ewell, posted near Gordonsville, to move part of his division toward

Swift Run Gap in the Blue Ridge, to connect with Jackson.

Thinking to take the initiative as soon as opportunity presented itself, Lee was not keen to give up the sixty miles of ground between Yorktown and Richmond without a fight, much less give up the navy yard at Norfolk which would mean the abandonment of the Virginia and the opening of James River to the enemy's naval operations. Furthermore, Johnston was banking on a concentration of force at Richmond that brought troops from the Carolinas and Georgia, troops that were needed where they were, protecting not only Charleston and Savannah but also the Savannah-Charleston Railroad from the enemy's attacks. Finally, accepting Johnston's forecast of a turning movement on Yorktown by the York River, there still remained many miles of terrain, as far as Lee was concerned, between the headwater of the York River at West Point and Richmond in which excellent fields of battle for a small army could be found. Taking advantage of these fields would give the Government time to outfit and drill the 30,000 young men of Virginia that the State had just conscripted to defend itself against the enemy's advance on Richmond.

President Davis, after listening without comment to the arguments, pro and con, adjourned the meeting, asking Johnston to return for a further conference. That evening, at 7:00 p.m., the discussion reconvened and continued until the early morning hours of April 15 when Davis announced his decision that Johnston was to hold the Yorktown line until such time as his army was seriously threatened with the enemy's flanking movement, or the Yorktown lines were on the verge of being broken. On April 17, Johnston assumed command of all Confederate forces on the Peninsula, including those at Norfolk and, with his troops working feverishly to strengthen the position's defenses, he waited for the moment McClellan's big siege guns opened.

During the subsequent weeks of April, anticipating Johnston's fall back on Richmond, General Lee spent the days on horseback, riding the developing lines of entrenchments that were being built by African slaves and, to their discomfort, soldiers. The Richmond newspapers railed in headlines against this, but he persisted; at the same time calling to Richmond what regiments he could spare from the South. Though using all his skills as an engineer to build an impregnable line of fortifications on the west bank of the Chickahominy, General Lee was still thinking of the moment the Confederate forces might seize the initiative from Lincoln. On April 29, just as McClellan had finally gotten his big guns within range of Johnston's entrenchments, General Lee sent this to Stonewall Jackson.

HEADQUARTERS, RICHMOND, April 29, 1862

Major-General T.J. Jackson, commanding, etc, Swift Run Gap.

General: From the reports that reach me the enemy's force at Fredericksburg is too large to permit me to reduce the force I have opposing it, as, if I do, it will invite an attack on Richmond from that direction and endanger the safety of General Johnston's army on the Peninsula. Can you draw General Edward Johnson's command from Staunton to you? His returns show he has about 3,500 men. A successful blow against Banks's column would be fraught with the happiest results and I deeply regret my inability to send you the reinforcements you ask.

Very Truly Yours, R.E. Lee

Richmond Defenses, 1862

The stage was now set for the epic struggle between the Union and the Confederacy that would decide the issue of how long the war was to last, and the fact that it was decided that the war would continue to the last ditch was in large measure due to General Lee.

At the same Lee wrote to Jackson, setting him in motion again toward the Potomac, his youngest son, Robert, who was a student at the University of Virginia at the time, tells us that, "My father allowed me to volunteer, and I joined the Rockbridge Artillery. My father gave his time and attention to the details of fitting me out as a private soldier. I do not suppose it ever occurred to my father to think of giving me an office, which he could easily have done, nor did I ever hear from anyone that I might have been given a better position because of the prominence of my father. With the good advice to be obedient to all authority, to do my duty in everything, great or small, my father bade me good-bye, and sent me off to the Shenandoah Valley where my battery was serving under Stonewall Jackson." |

Joe Ryan

I

The Origin And Object Of The War

II

The War In The West

The Hornets Nest

Union Control Of The Mississippi River

Papers of Ulysses S Grant

| Read all the Civil War Sesquicentennial articles | Comments and Questions to the Author |

|

Joe Ryan Original Works @ AmericanCivilWar.com Joe Ryan Video Battlewalks |

|

| About the author: Joe Ryan is a Los Angeles trial lawyer who has traveled the route of the Army of Northern Virginia, from Richmond to Gettysburg, several times. |

||

Battle of Gettysburg

General Robert E. Lee

General JEB Stuart

General Jubal Early

Confederate Commanders

General Joseph Hooker

Union Generals

American Civil War Exhibits

State Battle Maps

Civil War Timeline

Women in the Civil War