| Read all the Civil War Sesquicentennial articles | Comments and Questions to the Author |

II

The War in the West

| Union Control of the Missississpi River The Hornets Nest Papers of Ulysses S. Grant |

The Country Fails to Support Sidney Johnston

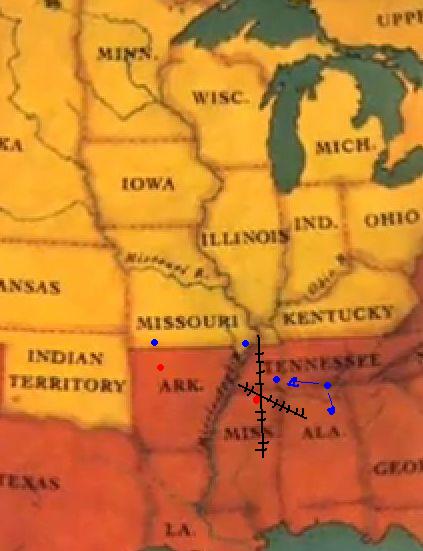

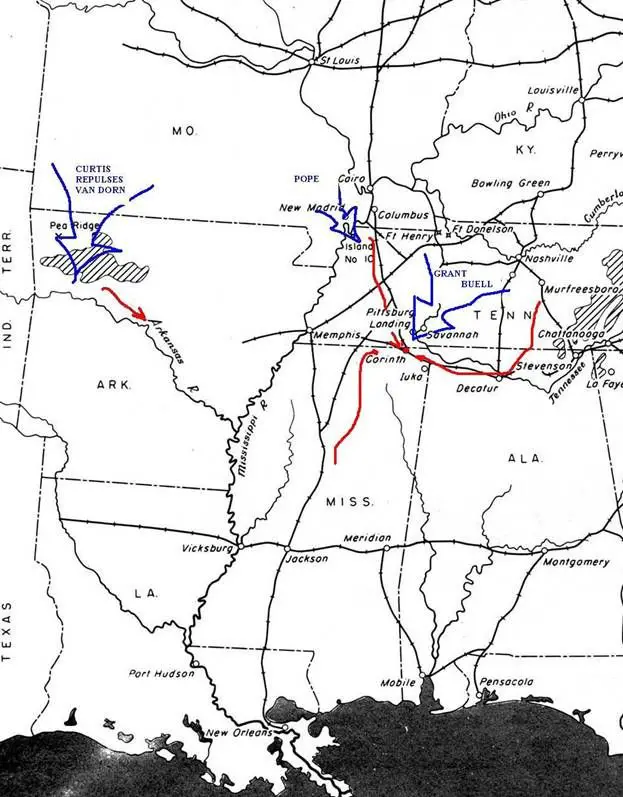

After the battle at Fort Donelson, Albert Sidney Johnston had marched from Nashville, south into the border region of Alabama and then turned west, reaching Corinth, Mississippi, on March 29, 1862. Waiting for him were the Army of Kentucky, commanded by Pierre Beauregard, and the Army of Mississippi, commanded by Braxton Bragg. Combining these with his Army of Tennessee, Johnston had present for duty about 40,000 men. He divided these into four army corps, commanded respectively by major-generals Hardee, Bragg, Polk, and Brigadier-General John C. Breckinridge. Beauregard, who was ill at the time, was designated as Second-in-Command.

Like the enemy they would soon encounter, very few of the men in the Confederate ranks of Sidney Johnston's army had experience in battle; many had just recently been mustered into service and there were more than a few still without rifles. Polk's army corps contained fifteen regiments; of these twelve were organized from young men of Tennessee who had, just weeks before, been drafted into service. The three remaining regiments were from Louisiana, Arkansas and Kentucky. Bragg's army corps contained nineteen regiments: six from Louisiana, six from Alabama, three from Mississippi, two from Texas, two from Tennessee, one from Florida, and one from Arkansas. Hardee's army corps was made up of twelve brigades: seven from Tennessee, three from Arkansas, and two from Mississippi. Breckinridge commanded thirteen regiments: four from Tennessee, three from Kentucky, two from Alabama, two from Arkansas, one from Missouri, and one from Mississippi.

Combining these regiments by state, we see that the Confederate Government had been able to assemble at Corinth, twenty four regiments from Tennessee; eight from Alabama, seven from Louisiana, six from Mississippi, six from Arkansas, four from Kentucky, two from Texas, one from Florida, and one from Missouri. This force, depending on your source, totaled 37,000 to 42,000 thousand men.

With Missouri and Kentucky gone to the Union. Tennessee was standing up for the Confederacy with twenty-four regiments to counter them. But the young men of Tennessee needed help to beat back the twenty-four regiments from Illinois, twenty from Indiana, and thirty-eight from Ohio that would mass at Shiloh. The combined regiments from Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana provided some help, but not much. Where was Texas? Where was Georgia? Not there.

The Union has the masses!

In contrast, The Union Government was bringing together at Pittsburg Landing, for an offensive against the strategic point of Corinth, almost one hundred thousand men. Grant's army at Pittsburg Landing was made up of six divisions, containing sixty-five regiments: of these 24 were from Illinois, 14 from Ohio, 11 from Iowa, 6 from Missouri, six from Indiana, one from Nebraska and one from Michigan. Five of these divisions, three of which were still in the process of being organized as Johnston arrived at Corinth, were concentrated on the west bank of the Tennessee River in a three by five mile space between Owl and Lick Creeks. The sixth division, commanded by Lew Wallace, was then camped about six miles north of this site at Crump's Landing, opposite Grant's base of operations at Savannah, Tennessee. This force, depending on your source, totaled about 35,000 to 40,000 thousand men.

The Union Staging Ground At Shiloh

Marching to join Grant, from the direction of Columbia and the Duck River, was Don Carlos Buell commanding the Army of the Ohio. He was bringing seventy-five regiments: 24 of which were from Ohio, 20 from Kentucky, 14 from Indiana, 2 from Michigan, 6 from Tennessee, and 1 each from Wisconsin and Minnesota. When Buell's force joined with Grant's, the Union would have about ninety-four thousand men to move forward against Corinth, to be resisted by Johnston's available force of 40,000.

It was no mystery to Sidney Johnston that soon there would be no fewer than ninety thousand men concentrated at Pittsburg Landing on the Tennessee River, just one good day's march from Corinth. The Union force was establishing itself deep in Confederate territory. It had to be driven away, or Corinth and the upper Mississippi Valley would be lost, but what was Johnston to do with only 40,000 men?

He had three choices: first, he might retreat immediately, deeper into Mississippi; second, he might stand in the fortifications being built around Corinth and await the arrival of the enemy; or, third, he might take the offensive and attack the enemy at Pittsburg Landing, perhaps destroy it against the bank of the Tennessee River, before the Army of the Ohio could arrive. Failing that, he might at least wreck its organization and gain the Confederacy time in which communication between the East and Louisiana, Arkansas, and Texas could be maintained.

Note: It was the Confederate Government's war policy to attack the enemy wherever it was found with equal numbers; its western armies did this in Tennessee, at Donelson, and in Missouri, at Wilson's Creek and Sedalia, and in Arkansas at Pea Ridge. To retreat without a battle now meant the Confederacy could not defend the upper Mississippi Valley.

Retreat for Sidney Johnston was out of the question

The Confederate army's line of retreat had to be down the Mississippi Central Railroad; there simply was no way the army could be supplied without it. Retreat would leave the enemy with possession of Corinth, Decatur and Memphis, it would result in the opening of Union navigation down to Vicksburg, and it would allow the enemy to terrorize the civilian population in the rural areas of Mississippi and Alabama. And the railroad junction at Jackson, Mississippi, would quickly come under pressure from the enemy advancing southward from Corinth. Communication would be in serious jeopardy of being lost between the Confederate States west of the Mississippi and those east of it. Union pressure would quickly build against Chattanooga, and Atlanta would be threatened.

The second choice—stand a siege at Corinth—was hardly any better; waiting for the enemy to arrive at Corinth meant that Pope's Army of Missouri, about 25,000 men strong, after breaking the Confederate hold on Island No. Ten, would join Grant and Buell, and then there would be 40,000 Confederates holding a fort against 125,000 men—just a plainly impossible task to perform.

The sum of all of this meant clearly, to any reasonable person's mind, that Johnston's retreat from Corinth meant that the Confederacy could not possibly win the war in the West militarily, because it could not stand concentrated in the field against the enemy. The enemy could move against the next stragetic point without fear of being seriously challenged by the Confederate army for possession. Alternatively, once in possession of a strategic point such as Corinth, the Union army could stop for a time and consolidate its grip on the conquered territory by establishing security. All that the Confederate Government could do, in such circumstances, would be to rely on guerilla warfare to harass the enemy by breaking its communications, thereby delaying the enemy's ability to either pursue the army southward, move east toward Knoxville and Chattanooga, or gain military control over the population. To win the war in the West, the Union armies had to do one thing or the other.

Sidney

Johnston never entertained for a moment the thought of adopting either one of

these two options—his mind on this was as a bar of iron. There was but one option,

under the circumstances of the case, and that was to attack the enemy at

Pittsburg Landing, attack them as quickly as possible. The battle for Corinth had no chance of success unless it was fought at Shiloh.

Sidney

Johnston never entertained for a moment the thought of adopting either one of

these two options—his mind on this was as a bar of iron. There was but one option,

under the circumstances of the case, and that was to attack the enemy at

Pittsburg Landing, attack them as quickly as possible. The battle for Corinth had no chance of success unless it was fought at Shiloh.

Never mind questions of supply, the miry tracks available as roads, the spring weather turning the ground into swampland, that Van Dorn in Arkansas could not arrive in time, the danger that Johnston's little army would be overwhelmed. A swift attack on the enemy at Shiloh created the chance that before Buell could come up, Grant's force might be beaten, beaten badly, perhaps forced by circumstance to surrender.

It would be a great set back for the enemy. It would energize the people. It would give the Confederate force in northwest Arkansas time to move east and across the Mississippi. Perhaps it might even result in the enemy moving back to regroup around Nashville. But no matter what happened, it would buy time.

THE PRESIDENT, Richmond THURSDAY, APRIL 3, 1862

General Buell is in motion, Buell moving rapidly from Columbia to Savannah, leaving a division of 10,000 moving toward Decatur. Confederate forces, 40,000, ordered forward to offer battle near Pittsburg. Hope engagement before Buell can form junction.

A.S. JOHNSTON

HEADQUARTERS ARMY OF THE MISSISSIPPI

Corinth, Miss., April 3, 1862

Soldiers of the Army of the Mississippi:

I have put you in motion to offer battle to the invaders of your country. Remember the precious stake involved; remember your mothers, your wives, your sisters, your children depend on the result; remember the fair, abounding land of ours, the happy homes that would be desolated by your defeat.

The eyes and hopes of eight million people rest on you. Show yourselves worthy of your race, worthy of the women of the South. With such incentives as these, your general will lead you to the combat, assured of success.

A.S. JOHNSTON, General

The Confederate March to Shiloh

"When people are oppressed by their government,

It is a natural right they enjoy to relieve themselves of the oppression.

But any people who resort to this remedy, stake their lives and property on the issue."

Ulysses S. Grant

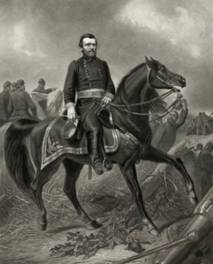

On Friday evening, April 4, in a driving rain storm, General Grant rode out of the Union camps around Shiloh Church and cantered up a track that led through the wilderness of forest, flooded streams, and tangled swampy ravines toward a crossroads that lay just beyond a ridge called Pebble Hill. Earlier Sherman had reported that several of his pickets had been captured by rebel cavalry; in response he had sent a company of infantry forward and followed with a brigade some four or five miles, stopping and withdrawing when the company in advance received artillery fire. Now Grant was riding out to see.

And as he rode he felt the tension, heard the occasional muffled sound of wagon wheels rumbling and what sounded like distant rifle cracks, caught glimpses of blurred movement flickering between the trees. They were coming, he thought—the signs are clear—and the master horseman suddenly pulled the reins to turn his mount around.

The horse neighed, surprised, and raised his forelegs off the ground, quarter-turned in the darkness and came down hard, one hoof hitting a fallen tree trunk, and Grant and his horse crumbled, the horse slamming down on him, trapping his boot in the stirrup.

Grant's aides came to him immediately, some pulling him by the arm pits as others grabbed the horse's reins; the horse gathering his weight on his fore legs, lifting his belly up as Grant came free from under him. In the saddle again, his wrenched ankle throbbing but no other damage done, Grant pranced the animal back through the woods, into the campgrounds of his army and rode to the Landing; taking his horse on board the gunboat, Tigress, he went into a cabin as the vessel pulled away from the wharf, turned in the river and headed downstream.

When he reached Savannah, an hour and a half later, he went into his headquarters telegraph tent and had this message sent to Henry Halleck: "I have scarcely the faintest idea of an attack being made upon us, but will be prepared should such a thing take place." Then a message came by gunboat from Sherman.

PITTSBURG LANDING

April 5, 1862

General Grant:

Sir: All is quiet along my lines now. We are in the act of exchanging cavalry, according to your order. The enemy has cavalry in our front, and I think there are two regiments of infantry and one battery of artillery about two miles out. I will send you ten prisoners of war and a report of last night's affair in a few minutes.

W.T. SHERMAN, Brigadier-General Commanding

Later that day, Sherman sent this to Grant: "I have no doubt nothing will occur today more than some picket firing. The enemy is saucy, but got the worst of it yesterday, and will not press our pickets far. I will not be drawn out, and I do not apprehend anything like an attack on our position." Grant followed this with a message to Halleck.

SAVANNAH, April 5, 1862

Maj-Gen. H.W. Halleck, Saint Louis, Mo.

The main force of the enemy is at Corinth, with troops at different points east toward us. The number of the enemy at Corinth cannot be far from 80,000 men. Information obtained through deserters place their force west of us at 200,000. One division of Buell's army arrived yesterday. General Buell will be here himself today. Some skirmishing took place with our pickets and the enemy's yesterday and the day before.

U.S. GRANT, Major-General

What accounts for Grant's conduct, in leaving the historical impression that the Confederates' "main body" was still at Corinth on April 5, instead of acknowledging in his April 5 writings that the woods in front of Shiloh Church were crowded with enemy soldiers advancing against his front? In light of his conduct at Fort Donelson, the answer seems obvious: Grant didn't care if he was attacked, indeed he hoped he would be attacked, the sooner the better. He was where he was because he had not flinched from moving against the rebel forces at Donelson, in doing it he had counted on the reinforcements that Halleck was moving up the Tennessee to guarantee him success in the endeavor, and now he was counting on Buell to reinforce him and guarantee a similar success. Grant knew the Union had the masses and that the sooner they were used the better.

Grant had good reasons for thinking he could handle a general attack by the enemy, if it came. He had gunboats in the river at Pittsburg Landing which could support him in the event of reverse, and Buell's army was now within less than a day's march from the place. Most important, there was no question about it, Grant's position on the west bank was a formidable natural fortification. There were two roads that approached Shiloh Church from the direction of Corinth, but they passed through dense forest along narrow ridges as they closed to the front, with impassable streams, gullies and morasses on their flanks. The tangle of ravines created very broken ground, with elevations falling 400 feet in places, and in the troughs the drainage of the heavy rains was running, and there were many boggy places in the swells that made the roads impassable for artillery, and difficult even for infantry. A general attack made by the enemy, their sweeping lines extending to Cow Creek to the north and Lick Creek to the south would be broken up by these successive barriers and the battle action would naturally be funneled into the narrow space between the ravines where the Corinth road was carried to the river bank at the landing.

That this was understood by Grant and his subordinate generals the record makes clear. In a letter written to Grant when he first arrived at Shiloh, Sherman said the position was "a military point of great strength." On the next day, he said he was "strongly impressed with its advantages." And when testifying at the court martial of a colonel after the battle, Sherman said, "On the 6th of April, you might search the world over and not find a more advantageous field of battle, flanks well protected (by the streams and gullies), troops in easy support, timber and broken ground giving good points to rally; and the proof of it is that forty-three thousand men, of whom at least ten thousand ran away, held their ground against sixty thousand chosen troops of the South, with their best leaders." (Well, not quite.)

|

In his memoirs, revealing what he no doubt believed Grant was thinking, Sherman wrote this. "We were an invading army; our purpose was to move forward in force, make a lodgment on the Memphis & Charleston Road, and thus repeat the grand tactics of Fort Donelson, by separating the rebels in the interior from those at Memphis and on the Mississippi River. We did not fortify our camps against an attack, because we had no orders to do so, and because such a course would have made our raw men timid."

Sherman had said the same thing, back at the time of the colonel's court martial for abandoning his post as his regiment was overrun by Hardee's soldiers coming against Sherman's front. "What business is it of his whether I invited an attack or not? he said. "To have erected fortifications would have been an evidence of weakness and would have invited an attack." (Huh? On the contrary it would have discouraged attack.)

The record is clear that no sooner had Buell's army rescued Grant's from disaster, with the rebels retreating on the second day, but Sherman made orders which contained the following paragraph: |

"Each brigade commander will examine carefully his immediate front. He will cause trees to be felled to afford his men barricade, and clear away all underbrush for two hundred yards in front; with these precautions we can hold our ground against any amount of force that can be brought against us." |

Out of the forest with horrible yells the rebels came

It is hardly surprising that General Grant did not adopt Sherman's entrenchment order before the battle of Shiloh occurred. From the moment he became a brigadier and gained command at Cairo, Illinois, he was champing to get the troops under his command into action; leading them against Pillow's force at Belmont, across the river from Columbus, Kentucky; pestering Halleck to let him loose on Fort Henry; and, then, without waiting for orders, moving on his own initiative directly on Fort Donelson. In doing this, Grant clearly exhibited nothing but distain for the ability or willingness of the Confederates to engage him in battle, banking every step of the way into the interior of Tennessee that he would always be able to bring to bear in time against the enemy, overwhelming man power.

Solidifying this attitude in his mind, must have been the fact that he knew Donelson had made him a household name, that the country was watching him, waiting to see what happened next. McClellan's army was now at Fort Monroe, gathering itself to move up the Yorktown Peninsula, to force its way into Richmond. Certainly there would be battles fought there that would draw the country's attention, and one way to bring it back to the West was for Grant to fight one as soon as possible.

Note: From a trial lawyer's point of view, the evidence is clear that, in fact, Grant invited Johnston to attack; First, he did not order fortifications because he knew their presence would be reported to Johnston by Forest's cavalry and then the Confederate commander would have no choice but to back off. Second, he ordered Sherman, when he left him the morning of the 5th, to pull back the Union cavalry so no alarm would be given his troops. Sherman was his coconspirator in this.

The young men in the ranks, Grant surely knew, were the most important factor. So far, in the war, there had only been one general battle, and that was at Bull Run. McDowell's army of raw recruits—not much different in that respect than Grant's at Shiloh—had cut and run, had given the rebels a great victory and the Union a great defeat. Donelson didn't count enough to erase the taste of it, but, now, the full power of the Union in the west was gathering at Shiloh and the young men—like their counterparts coming toward them in the forest—were still untested, untried by the fire. They were eager to fight, that's for sure, their minds flushed with the excitement of the endeavor—the mustering in their towns, the marching from their camps, the steamboat ride up the Tennessee, the camping in this place; all of them feeling strong in their numbers, anxious that they do better in their baptism of fire than their fellows had done at Bull Run. It was like the student bodies of two hostile schools coming together on a field to play rugby in the mud.

Sherman revealed Grant's true mind-set, in the run up to the battle, in a letter he wrote to a magazine, in January 1865: "It was necessary that a combat should come off, to test the mettle of the two armies and Shiloh was as good a place as any."

The General Officers

In the coming battle, the success or failure of the men in the ranks would depend, in the end, not so much upon themselves, but upon the officers that led them in the struggle. These officers, and their subordinates handling the individual regiments, were responsible to give the men direction and control as the battle unfolded, massing them where they were needed, reinforcing them, rallying them, keeping the ammunition coming, the artillery in proper position firing. Sidney Johnston's son, Preston, summed the essence of this up, when he wrote after the war—"Once in the presence of the enemy, the result depends upon the way in which the troops are handled."

Of Grant's five division commanders present at the battle, four were lawyer-politicians from rural areas of Illinois and owed their commissions to the fact they were friends of Lincoln. Only the fifth, William Sherman, was a career military officer and graduate of West Point. None of them had any appreciable experience in handling men in the environment of battle; indeed, three of them—Stephen Hurlbut and Benjamin Prentiss (one-time superiors to Grant) and William Sherman—had arrived at Pittsburg Landing only days before the battle and had the chore of assembling raw men into divisions as the regiments arrived, piece meal, on steamboats. The other two—John McClernand and William Wallace—though uneducated in military affairs, had been with Grant at Donelson and experienced being pushed back by Pillow's attack. Presumably they learned something from the experience. Lew Wallace, another lawyer-politician, who gained his commission through friendship with Indiana Governor Morton, was at Crump's Landing throughout the entire battle and, thus, played no role in the first day's struggle.

In contrast five of the six general officers that led the young men of the Confederacy to battle at Shiloh were West Point graduates. Two of them—Sidney Johnston and Pierre Beauregard—were within the first flight of Confederate commanders; Johnston ranked by President Davis second, and Beauregard ranked fifth. Johnston, Beauregard, Bragg, and Hardee had seen significant action in the War with Mexico and were career army officers when the war broke out. Polk was a West Point graduate, too, but had left the Army. Only John Breckinridge, commanding the reserve at Shiloh, was a lawyer-politician, though even he made it to Mexico as a major in a volunteer Kentucky regiment. It was going to be Illinois politicians vs Confederate West Point.

Sidney Johnston Plans The Battle

The Night Before Shiloh

April 5th had been a dismal day: Sidney Johnston had ordered his corps commanders to get their divisions into line of battle by 8:00 a.m., at which time the attack on Grant's camps was to commence; but because of the incessant rain storms that turned the dirt forest tracks into swamp, confusion occurred in the movement forward of the divisions in Bragg's corps and the Confederate front was not established until 4:00 p.m.; too late to attack that day. But for this one day's delay, there can be no serious doubt that the Confederate army would have either forced the surrender of Grant's army before Buell's army could arrive to save it, or driven it up the road to Crump's Landing.

The Confederates lose a fateful day launching their attack.

One of the Confederate brigadiers wrote after the war about this day: "You know I was as ignorant of the military art at that time as it was possible for a civilian to be. I had never seen a man fire a rifle. I had never heard a lecture or read a line on the subject. We were all, the rawest and greenest of recruits—colonels, captains, soldiers."

No doubt angry, frustrated, and disappointed with the outcome of the day, Sidney Johnston sat down that evening on a log in the forest, not more than two miles from Shiloh, and listened to the council of his corps commanders.

Pierre Beauregard,

the "hero of Sumter" and the general in tactical charge of the

battlefield at Bull Run, was adamant that the attack should be abandoned. The

delay in getting the army up from Corinth and into line of battle, he said, had

given the enemy ample opportunity to recognize there were masses building up in

their front and no doubt they had spent the day cutting down trees, to clear

their range of fire, and constructing barricades.

Pierre Beauregard,

the "hero of Sumter" and the general in tactical charge of the

battlefield at Bull Run, was adamant that the attack should be abandoned. The

delay in getting the army up from Corinth and into line of battle, he said, had

given the enemy ample opportunity to recognize there were masses building up in

their front and no doubt they had spent the day cutting down trees, to clear

their range of fire, and constructing barricades.

Thinking of his experience at Bull Run, Beauregard knew the enemy, here, could repulse Johnston's attack as Jackson's lines had repulsed McDowell's on Henry Hill. Furthermore, the delay meant that it was now probable Buell's army would be up in time to support Grant's in the battle. Outnumbered, then, by two to one, the attacking force could not accomplish much. In his calculus of the situation, he said, retreat was now essential.

Braxton Bragg chimed in; supporting Beauregard's assessment with the argument that the men had eaten all their rations, that there had been much firing of rifles among the raw men, and that the enemy was probably entrenched now, making the success of the attack unlikely. And what about Buell; he would most certainly now be up in time. Polk and Breckinridge remained silent. Hardee was absent.

When everyone had their say, Sidney Johnston rubbed his face with a hand and looked intently at Beauregard; from a purely tactical point of view, he knew Beauregard was probably right. There had been constant contact between cavalry, and skirmishing between pickets had been going on during the two days the army moved up to Shiloh. It was impossible to reasonably believe the enemy did not know the Confederates were massed now in their front, poised to give them a general battle. Under such circumstance, it was unrealistic to think the enemy front was not now entrenched. Bull Run had proven the tactical advantage the defense had over the offense in actual battle, and now Johnston was in McDowell's position, his masses charging artillery defended by a fortified front. And it was true that the men were wet to the bone, already tired and hungry. But they were still fired up, in high spirits, eager for the battle; and the effect of an order to retreat, after they had come this far, would depress their spirits, disappoint them, make them feel depreciated. The order to retreat would be almost as bad as a defeat, and the enemy were, in fact, still divided and as a consequence there was still a good chance Grant's isolated position could be exploited.

Mulling the issue in his mind, Johnston reached into a pocket and pulled out a letter and a telegram he had received. He had read them already several times, now he read them again.

RICHMOND, March 26, 1862

My Dear General: I need not urge you to deal a blow at the enemy in your front, if possible, before Buell gets up. You have them divided, and keep them so, if you can. Wishing you, my dear general, very success, with my earnest prayers for the safety of your army, I remain, truly and sincerely,

Your friend, R.E. Lee.

RICHMOND, April 5, 1862

General A. Sidney Johnson, Corinth, Miss.

Your dispatch of April 3 received. I hope you will be able to close with the enemy before his two columns unite. I anticipate victory.

JEFFERSON DAVIS

Running his tongue between his teeth as he read, Sidney Johnston knew with absolute certainty what he had to do. I would attack them if they were a million, he thought to himself. Stuffing the papers back in his pocket, he rose from the log and looked Beauregard in the eye. "We will attack them in the morning," he said coldly. "You will remain in the rear and manage the reserves and coordinate the movements of the lines. I will be at the front and push the attack where I can." Then he mounted up and rode to the front.

Grant Gets Hammered

|

On April 6th, at Savannah, General Grant woke up in a featherbed in the upstairs bedroom of William Cherry's mansion overlooking the Tennessee River. About six o'clock, he came downstairs and sat down at the dinner table to eat breakfast with his staff. As bread and butter was being passed, the dull sound of artillery concussions was heard coming from somewhere down the river. At the sound, those at the table froze and listened, some with bread in their mouths, others with cups of coffee in their hands.The sound began faintly, but now it was becoming louder and continuous like the rumbling of an approaching freight train. |

After a minute of this, Grant shoved his chair back and went into the next room where his Adjutant-General, John Rawlins, had his office and in a raspy voice dictated two curt messages. The first went to Brigadier-General William Nelson, commanding Buell's lead division which had arrived at Savannah the night before: We are attacked at Pittsburg. Move your division up the right bank of the river, it read. The second was sent to Don Carlos Buell; like Nelson, he had arrived at Savannah while Johnston was conferring with Beauregard in the Tennessee wilderness, but had not yet reported to Grant—as a Regular Army brigadier, he felt submission to Grant's volunteer rank demeaning. "Heavy firing is heard up the river," Grant wrote; "I have been looking for this, but did not think it would come before you were up." Then he raced for the riverfront, to board the Tigress. |

|

The Cherry Mansion on the banks of the Tennessee

Steamboats at Pittsburg Landing

Two hours later, Grant came off the Tigress, clamoring down the ramp on his horse, and galloped up the bank and out on to the Corinth road amidst thousands of breathless soldiers running pell mell past him in a mob toward the river. By the end of the day ten thousand of Grant's soldiers would be packed in a solid mass under the river bluff. Reining up on the road between two ravines, he listened to the tremendous racket of rifle fire, artillery explosions, mixed intermittently with curdling yells and shouts of the masses of men in combat a mile in front of him in the woods. Gauging it, Grant realized the sound was coming closer and he whirled his big stallion and galloped back to the landing, and shouted orders to his staff to get wagons loaded with ammunition from the steamers and hurry them to the front. Then, with hardly a pause, he was back on the road, galloping to the sound of the guns.

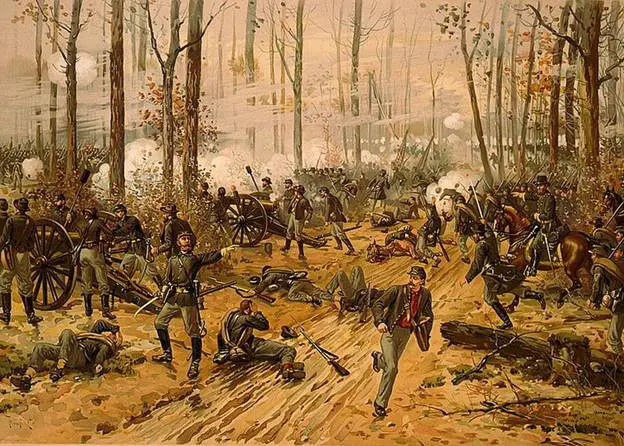

What he found was an impending disaster. Long compact lines of gray and brown clothed soldiers were fighting with a sustained fury, coming out of patches of woods and across the open fields, driving his soldiers before them, filling the gaps in their lines with new faces as the whole mass of bodies moved. On the right, Sherman's division had been almost swept away in the first onslaught. The 53rd Ohio Regiment had evaporated at the first rifle volley, the men, led by their colonel, running for the rear, shouting, "Fall back, fall back," to the men in the ranks forming behind—"save yourselves!" The colonel of the 71st Ohio had abandoned his place the moment the first bullets flew, and the organization of the regiment collapsed into a stampede. The 6th Iowa, with its colonel, drunk, huddled in disorganized groups in the ravines. The solid wave of rebel soldiers—Hardee's and Bragg's men—had driven Sherman back from Shiloh Church a mile, and had Prentiss's division falling back across a wide field and disappearing into a strip of forest.

Shoring up Sherman and Prentiss by this time were the regiments of McClernand's and Hurlbut's divisions, the men fighting desperately to hold the ridges of the ravines and the roads that ran between. Grant rode to his right first—to Sherman's sector—and found him unhorsed and shot. But, standing in a tree line, with missiles flying all around, he looked at ease, in his element, and he called out to Grant, "More ammunition!"

Waving him an

acknowledgement, Grant wheeled round and galloped through underbrush, whipping

his horse past trees and down and out of a ravine and came up behind Prentiss's

men. Bragg's men, supported by some of Breckinridge's, had swarmed through

Prentiss's camp, making his men fall back across a fallow farm field, to a

wagon-rutted road at the edge of a stretch of woods. Here Grant found him,

steadying his men, getting his artillery into action and breaking Bragg's

attack, the intense fire making Bragg's men stop their advance and slip back

from the field and into the forest around it. And then they were coming on again.

Waving him an

acknowledgement, Grant wheeled round and galloped through underbrush, whipping

his horse past trees and down and out of a ravine and came up behind Prentiss's

men. Bragg's men, supported by some of Breckinridge's, had swarmed through

Prentiss's camp, making his men fall back across a fallow farm field, to a

wagon-rutted road at the edge of a stretch of woods. Here Grant found him,

steadying his men, getting his artillery into action and breaking Bragg's

attack, the intense fire making Bragg's men stop their advance and slip back

from the field and into the forest around it. And then they were coming on again.

Grant left Prentiss to carry on, and galloped back toward the landing, stopping when he found William Wallace coming up, directing him to the sector Prentiss was defending. Leaning down, he gripped Wallace by the shoulder and shouted over the din, "Prentiss has command of the road to the landing. You must help him keep it!" And he was flying again, looking for Hurlbut and when he found him, pointed toward where Prentiss was fighting and yelled at him," Get over there!"

An hour later, Grant was back at the bank of the river, making a log cabin on the bluff his headquarters. He ordered a courier to ride to Crump's Landing and guide Lew Wallace's division to the battlefield and he wrote a message to Buell, sending it by a courier who crossed the river on a gunboat and then took the road to Savannah. The note read: "If you can get upon the field it will probably save the day to us." He had brought them to it, and now they were in the shit.

It was now becoming late afternoon, the fighting had been raging incessantly since dawn, the rebels pouring in their forces, the Union men giving ground on both flanks, falling back, regrouping, making a stand, falling back again. Prentiss, supported by Hurlbut, had about 4,500 men and two batteries of artillery and was refusing to let go of the sunken road at the edge of the forest in the center, beating off attack after attack; though the attacks were lapping at his flanks, at times almost surrounding him. Prentiss proved that day he was the best.

The Hornets Nest

The battle went on hour after hour, all but Prentiss at what now's known as the hornets' nest being driven back closer and closer to the river bank. Sidney Johnston was in the midst of this,careless of the sipping bullets and the artillery crashes, riding his stallion forward with the rebel waves, sending messages to Beauregard to release more men from the reserves, directing their officers to bring them always to the right, keeping the pressure up on the hornets' nest, until finally, late, very late in the day, he had Prentiss's position surrounded and, with no chance now to escape, Prentiss surrendered just as General Wallace was killed by rifle fire, the young men of Tennessee pouring the rounds into the blue ranks at point blank range.

A momentary lull ensued as the rebel soldiers lost their composure at the sight of the white flag, and they began straggling, falling out of ranks, enjoying their hard won victory; but then Johnston came galloping up the road, waving his sword over his head, barking orders and soon everybody was reformed into a compact front and moving forward through the woods again, moving up the Landing road, fighting their way through the peach orchard and the bloody pond and came upon Grant's last stand.

In this last advance of the day, Sidney Johnston was left behind; shot from his horse as he showed the men the way to the road, he fell to the ground, the blooding draining from his body through a severed artery and almost instantly he died.

Grant's Last Stand

It was Beauregard's army now and he was busy, with a handful of staff officers, rounding up stragglers to form improvised battalions to rejuvenate the waning rebel front. Meanwhile, Grant was organizing all the field artillery he could find and rushing to form a compact line on the north side of a deep ravine that ran about a half mile inland from the Tennessee. In the woods bordering a long ravine that reached down from the north almost to where Prentiss had made the decisive fight of the battle, rebel artillery pounded Grant's position, sending shells crashing into the boats still moored at the landing. A staff officer was killed by one of these shells, standing at Grant's side. Whitelaw Reid, a Cincinnati newspaperman came up to Grant and said, as the missiles rained down, "Had you better not get the men moving out of here?" "Oh no," Grant replied in a dismissive voice. "They can't break our lines now, it's too late. Tomorrow we will drive them away, of course."

Grant counting his losses

The Second Battle of Shiloh

At the moment the rebel forces were pressing in upon Grant's desperate stand in his magazines, Nelson's division of Buell's army appeared on the right bank of the Tennessee. In one long column, as dusk fell on the bloody day, it crossed the river on a pontoon bridge, the last planks sliding into place as pioneers closed the channel gap. The troops marched up the cut in the bluffs, forcing out of the way Grant's soldiers pressing close to the river and falling into line behind the field pieces still banging away at the enemy massed in front. Skirmishers from the 9th and 10th Mississippi regiments, Chalmer's brigade, were within a hundred yards of the guns, knelling and firing at the cannoneers when Nelson's men formed front and let loose a tremendous volley that swept the field clear. The battle of April 6th had finally ended, twelve hours after it began.

Relative Positions Morning of April 7th

Grant's army had been wrecked: Besides the five thousand men of Lew Wallace's division which arrived from Crump's Landing as night fell, Grant had seven thousand men at most in line of battle when the first brigades of Nelson's division crossed over the Tennessee and repulsed the rebels' last attack against Grant's left. Of Grant's original force, 7,000 were dead or wounded, 3,000 were prisoners, and 15,000 were cowering under the river bluffs, thoroughly disorganized. Thirty of Grant's guns were in the possession of the enemy.

Don Carlos Buell, arriving by steamer from Savannah that night, walked Grant's lines and recorded his impression:

"An unbroken tide of disaster had obliterated the distance between grades. The feeble groups that still clung together were held by force of individual character more than by discipline, and a disbelief in the ability of the army to safely extricate itself from the peril enveloping it, was, I do not hesitate to affirm, universal. In my opinion, that feeling was shared by the commander himself. A week after the battle the army had not recovered from its shattered and prostrated condition."

Buell's division commander, William Nelson, echoed his view of things when he wrote in his official report:

"I found cowering under the river bank when I crossed from 7,000 to 10,000 men, frantic with fright and utterly demoralized, who received my division with cries, `We are whipped; cut to pieces." There were insensible to shame or sarcasm."

Indeed, on April 14, when Henry Halleck arrived at Pittsburg Landing, he confirmed Buell's assessment with this order he caused to be delivered Grant:

"Divisions and brigades should, where necessary, be reorganized and put in position, and all stragglers returned to their companies and regiments. Your army is not now in condition to resist an attack."

Secretary of War Stanton sent this message to Halleck upon his arrival at Pittsburg:

"The President desires to know why you have made no official report to this Department respecting the late battle at Pittsburg Landing, and whether any neglect or misconduct of General Grant or any other officer contributed to the sad casualties that befell our forces on Sunday."

Halleck answered Stanton by telegraph

"It is the unanimous opinion here that Brig. Gen. W.T. Sherman saved the fortune of the day on the 6th instant, and contributed largely to the glorious victory on the 7th. He was in the thickest of the fight on both days, having three horses killed under him and being wounded twice. I respectfully request that he be made a major-general of volunteers, to date from the 6th instant.

The sad causalities of Sunday, the 6th, were due in part to the bad conduct of officers who were utterly unfit for their places, and in part to the numbers and bravery of the enemy. I prefer to express no opinion in regard to the misconduct of individuals till I receive the reports of commanders of divisions. A great battle cannot be fought or a victory gained without many casualties." (Halleck was promoting Sherman because Sherman was his friend. Prentiss saved the day, not Sherman.)

For General Grant's part, he was oblivious to the criticism, and it must be said for good reason. The Government had put the men into blue uniforms to fight the enemy, and there was no point fussing about it. Lincoln's Government had the masses and using them was the only way the war would ever end. Lincoln knew this in his hard heart and was grateful the Union had the benefit of Grant's generalship and proud he was an Illinois man..

Late in the day of April 7th, Grant sent Halleck this message:

"Yesterday the rebels attacked us here with an overwhelming force, driving our troops in from their advanced position to near the landing. General Lew Wallace was immediately ordered up from Crump's Landing, and in the evening, one division of General Buell's army arrived. During the night Crittenden's division arrived, and still another today. This morning, at the break of day, I ordered an attack, which resulted in a fight, which continued until late afternoon, with severe loss on both sides, but a complete repulse of the enemy. I shall follow tomorrow far enough to see that no immediate renewal of an attack is contemplated."

Grant followed this, with further report in April 9th:

"During Sunday night I ordered an advance as soon as day dawned. The result was a gradual repulse of the enemy at all parts of the line from morning until near 5 o'clock in the afternoon, when it became evident that the enemy was retreating. My force was too much fatigued to pursue immediately. General Sherman, however, followed the enemy a distance, finding that they were retreating in good order."

Buell's army attacks the enemy

At 7 o'clock, three divisions of Buell's army, combined with fragments of Grant's, attacked the rebel front holding the ground behind Dill's Branch and were repulsed. They attacked again and again and were driven back. Buell lost many men in the process, but each attack whittled away at an already severely depleted rebel force which, in the lulls, retired to newly fortified positions in the forest behind. Hours were consumed in the endeavor, Buell's men charging forward, gaining ground then losing it again as the rebels rallied and countercharged. Buell came on again with heavier battalions and the rebels were again forced grudgingly, with much loss, to give a few hundred yards of ground.

At one point,

a Confederate officer seized the colors of the Ninth Mississippi Regiment,

which had fallen back almost to the bloody pond near where Johnston had been

killed, and called for a charge. With wild penetrating screams of menace and

resolve, the barely two hundred men left standing in the regiment rushed

forward and regained the lost ground, holding it for twenty minutes until blue

masses came against them again. Back and forth the battle went on the Landing

road, but as the hours passed the diminishing strength of the rebel soldiers

began to show.

At one point,

a Confederate officer seized the colors of the Ninth Mississippi Regiment,

which had fallen back almost to the bloody pond near where Johnston had been

killed, and called for a charge. With wild penetrating screams of menace and

resolve, the barely two hundred men left standing in the regiment rushed

forward and regained the lost ground, holding it for twenty minutes until blue

masses came against them again. Back and forth the battle went on the Landing

road, but as the hours passed the diminishing strength of the rebel soldiers

began to show.

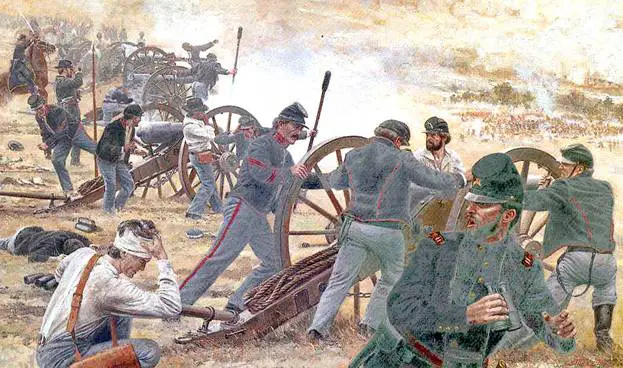

Here, on the Corinth Road, Breckinridge's two brigades, with the remmants of Hardee's brigades, held the gap between the ravines in front of the crossroads that Prentiss had held the day before. The rebel brigades were now manned by little more than a third their strength the day before, and in the charge of the whole body these were mowed down and reeled backwards by the constant pressure of Buell's reserves. Now, the battle scene broke down from organized resistance of infantry lines, to stubborn combats by groups of men in the woods—a hundred here, fifty there; charges, repulses, countercharges, surges of slaughter and fury, lulls and pauses in the heat and fury of the fray.

On the far right of the battle ground, Sherman's and McClernand's divisions, supported by Lew Wallace's, came in to action against the remnants of Polk's and Bragg's men, slowly gaining ground until they were fighting for possession of their old campgrounds. William Wallace's, Hurlbut's and Prentiss's divisions were gone from the scene and contributed nothing to the battle. Beauregard hurried forward two artillery batteries which unlimbered around Shiloh Church and the rapid fire of the guns decimated Sherman's ranks, staggered the men in their attack and caused them to fall back to the protection of the ravines that bordered the ground.

On the rebel

left, where Lew Wallace was fighting to get around the flank, Bragg ordered a

charge of the Fourth Kentucky Regiment, with Governor George Johnson in the

ranks, and the Fourth Alabama Battalion—the men rushing forward with curses and

screams, driving the enemy back on their second line. But, after a struggle of

twenty minutes, they were in turn driven back five hundred yards, with Johnson

mortally wounded and left on the field for dead; and Wallace's masses kept the

pressure up with great elation, pressing the rebels in the rear. But, yet

again, the rebels rallied and countercharged. The same ground was crossed and

recrossed four times. Regimental flags were captured and recaptured, the color

bearers killed, new ones taking their places killed. It was a terrible combat

On the rebel

left, where Lew Wallace was fighting to get around the flank, Bragg ordered a

charge of the Fourth Kentucky Regiment, with Governor George Johnson in the

ranks, and the Fourth Alabama Battalion—the men rushing forward with curses and

screams, driving the enemy back on their second line. But, after a struggle of

twenty minutes, they were in turn driven back five hundred yards, with Johnson

mortally wounded and left on the field for dead; and Wallace's masses kept the

pressure up with great elation, pressing the rebels in the rear. But, yet

again, the rebels rallied and countercharged. The same ground was crossed and

recrossed four times. Regimental flags were captured and recaptured, the color

bearers killed, new ones taking their places killed. It was a terrible combat

By early afternoon, the vortex of the battle having surged into the vicinity of Shiloh Church, Beauregard decided the weight of the Union force was too much to resist and he ordered withdrawal. The flow of the battle was like a train of waves slamming against a beach, the tide whipping in, meeting the resistance of the sand, and slipping away, gathering force under the impetus of the following wave and slamming in again. The process had worn down the rebel resistance to the point there was no hope left of victory. And in that moment of Beauregard's decision, the Confederate hold on Corinth was lost.

In the lull of a temporary success, Beauregard ordered Breckinridge to withdraw from the gap between the ravines and head west past Shiloh Church into the deep forest behind and get on the road to Monterey. First one line would withdraw, the front held by the second line, then that line would retreat. It happened slowly and in good order, the men taking with them their artillery batteries without loss. As Sidney Johnston's son, Preston, wrote: "The Confederate army retired like a lion, wounded but dauntless, that turns and checks pursuit by grim defiance in his face. The Union army was content to recover its campgrounds at Shiloh Church from which it had shrunk cowering and beaten the day before."

The only attempt to follow Beauregard's retreat through the forest was commenced on Tuesday, April 8th; a brigade from Sherman's division, accompanied by cavalry, marched several miles into the forest but were suddenly attacked by Forrest's troopers as the men were struggling through a stream-filled ravine that cut the road, and its organization collapsed, the men fleeing, seized by panic. Forrest's horsemen rode the Union men down with their horses, stabbing and slashing with sabers, shooting their pistols. Forest, wild with delight, ran his horse a mile down the road in the midst of the running men, slashing and cutting, until, coming out of the woods suddenly, he was met with a fusillade of fire from a volley line, was struck by a bullet in the stomach, his horse mortally wounded. Riding the animal as it was bleeding to death, he was able to escape into the forest.

The loss to the Union occasioned by these two days of battle was, according to official reports as follows: Grant's army suffered 1,437 killed, 5,670 wounded, 2,934 captured; Buell's army suffered 268 killed, 1,816 wounded, 3,002 captured, for a total of 12,217.

Beauregard, on Tuesday, sent a message to Grant, proposing that a Confederate burial detail be allowed access to the battlefield. Grant sent a reply the next day, stating there was no need as the dead from both armies were already under the ground. Grant's burial details put seven hundred Confederate soldiers in one grave.

Seven Hundred Unknown Sons of the South

Union Cemetery, Shiloh

To his political sponsor, Representative Washburn, Grant wrote, in the face of the storm of public criticism he received, "Those people who expect a field of battle to be maintained, for a whole day, with about 30,000 troops, most of them entirely raw, against 70,000 as was the case at Shiloh, whilst waiting for reinforcements to come up, know little of war." When it was convenient for him, Grant "forgot" the Confederates had fought him to the bank of the Tennessee with about the same strength his army possessed. The Confederate victory on April 6th belonged to West Point, the Union victory on April 7th belonged to Buell..

Henry Halleck Takes Field Command

Headquarters Department of the Mississippi

Saint Louis, April 9, 1862

General Grant:

Received your dispatch of the 7th about the battle at Shiloh, last night. I leave immediately to join you with considerable reinforcements. Avoid another battle, if you can till I arrive.

H.W. HALLECK, Major-General

Looking splendid in a crisp new uniform, Henry Halleck reached Pittsburg Landing on April 11 and walked down the gangplank of a steamer in the midst of a rain storm. What he found was not pleasant. Inspecting the campsites of the men, Halleck found skulls and toes of the dead sticking out of the saturated soil, crushed bodies floated in the ravine bottoms, droves of men were lying sick in tents, the food was awful, latrines nonexistent, and the whole place a morass of mud and debris.

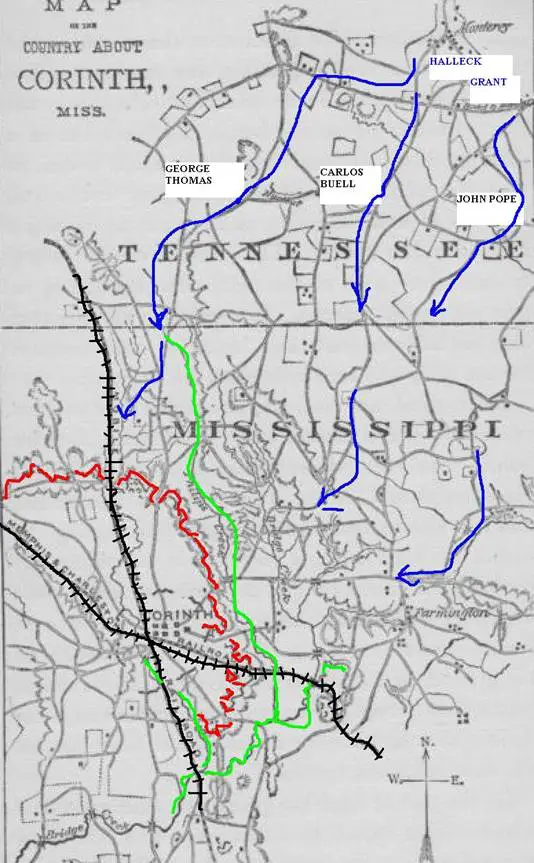

By this time, John Pope had routed the enemy holding Island No. Ten, and Halleck ordered him to bring his army of 25,000 men to Pittsburg Landing, by way of the Tennessee River. When Pope arrived on April 14th, Halleck now had at his command almost one hundred and twenty-eight thousand men, organized in three armies. Leaving Pope and Buell in command of their armies, he transferred Major-General George H. Thomas, with his division, from Buell's army to the Army of the Tennessee and removed Grant from field command, leaving Grant in administrative command of the department. The same hostility that had rankled between the two men in the run up to Shiloh was to continue, Halleck bypassing Grant in a number of ways and Grant reacting by asking, again, to be relieved.

A week later, Halleck began to move his huge body of troops westward into the forest taking the road to the crossroads at Pebble Hill and then the roads converging on Corinth. Progress was slow: At every stream crossing a bridge had to be built, and as the movement would end in a siege of undetermined length, it was necessary to corduroy the roads, a process of chopping down trees, cutting the trunks to length and laying them side by side across the roads. Lateral roads were also cut through the forest so that supply and artillery trains could move simultaneously with the infantry march. With Pittsburg Landing the army's base of operations, a depot of a huge amount of tonnage had to be built up, the tonnage being moved by wagon trains forward to the staging area in front of Corinth, the trains making round trips daily to keep the moving men and animals of the army supplied with food. It was a mammoth undertaking, reaching the scale of George McClellan's endeavor to move his army up the Yorktown Peninsula to Richmond.

Halleck's slow move toward Corinth

Grant paints the picture, in his memoirs:

"The enemy was constantly watching our advance, but as they were simply observers there were but few engagements that even threatened to become battles. All the engagements fought ought to have served to encourage the enemy. Roads were again made in our front, and again corduroyed; a line was entrenched, and the troops were advanced to the new position. Cross roads were constructed to these new positions to enable the troops to concentrate in case of attack. The Union army was thoroughly entrenched all the way from the Tennessee River to Corinth.

For myself I was little more than an observer. Orders were sent directly to the Army of Tennessee, ignoring me, and advances were made from one line of entrenchments to another without notifying me. My position was so embarrassing in fact that I made several applications during the siege to be relieved."

Here the

matter of military strategy requires a word. Henry Halleck and George McClellan

were intelligent, well trained officers, McClellan also a fine engineer.

Halleck had written extensively about military strategy and McClellan had

personally witnessed the effort involved in producing a major siege operation

of comparable size with that being now conducted at Corinth and Richmond, when he visited Sebastopol during the Crimean War. Sieges necessarily take time.

The besieging army must operate with a reasonable degree of caution in enemy

country. It must be very careful to establish and guard its line of

communication with its base of operation, so as not to be cut off and left to

starve in enemy territory. This effort requires the building of bridges, of

roads, the establishment of forward depots, the movement to them of vast

quantities of supplies. Once the line of communication is secure, the commander

must now approach the ramparts of the defenders of the spot at issue. This,

too, must be done carefully: trenches must be dug, ramparts built, to be used

to bring the infantry masses as close as possible to the enemy's

fortifications, before they are ordered to charge over the open ground; and

behind the infantry, heavy siege guns must be muscled into position, to provide

the infantry with a curtain of artillery fire it can move behind, the curtain

stepping closer and closer to the spot to be overrun as the trenches get

closer.

Here the

matter of military strategy requires a word. Henry Halleck and George McClellan

were intelligent, well trained officers, McClellan also a fine engineer.

Halleck had written extensively about military strategy and McClellan had

personally witnessed the effort involved in producing a major siege operation

of comparable size with that being now conducted at Corinth and Richmond, when he visited Sebastopol during the Crimean War. Sieges necessarily take time.

The besieging army must operate with a reasonable degree of caution in enemy

country. It must be very careful to establish and guard its line of

communication with its base of operation, so as not to be cut off and left to

starve in enemy territory. This effort requires the building of bridges, of

roads, the establishment of forward depots, the movement to them of vast

quantities of supplies. Once the line of communication is secure, the commander

must now approach the ramparts of the defenders of the spot at issue. This,

too, must be done carefully: trenches must be dug, ramparts built, to be used

to bring the infantry masses as close as possible to the enemy's

fortifications, before they are ordered to charge over the open ground; and

behind the infantry, heavy siege guns must be muscled into position, to provide

the infantry with a curtain of artillery fire it can move behind, the curtain

stepping closer and closer to the spot to be overrun as the trenches get

closer.

Quite

strangely, as we shall see, Abraham Lincoln seems to have had no problem with

allowing Halleck as much time, as much material, and as much men, as he

required to perform this necessary military activity, but when McClellan sought

to duplicate Halleck's effort—McClellan had sixty miles to cover getting to

Richmond, Halleck only twenty to get to Corinth—Lincoln became agitated, sarcastic,

and grossly uncooperative. Lincoln and his Illinois crowd had achieved perfect

success in their handling of military affairs in the West, but, to win the war

quickly, Lincoln had to duplicate that success in the East, but, then, he was

dealing with Virginia, not Tennessee, and he fumbled.

Quite

strangely, as we shall see, Abraham Lincoln seems to have had no problem with

allowing Halleck as much time, as much material, and as much men, as he

required to perform this necessary military activity, but when McClellan sought

to duplicate Halleck's effort—McClellan had sixty miles to cover getting to

Richmond, Halleck only twenty to get to Corinth—Lincoln became agitated, sarcastic,

and grossly uncooperative. Lincoln and his Illinois crowd had achieved perfect

success in their handling of military affairs in the West, but, to win the war

quickly, Lincoln had to duplicate that success in the East, but, then, he was

dealing with Virginia, not Tennessee, and he fumbled.

Both Halleck and McClellan concurred in the view that Corinth, in the West, and Richmond, in the East, were the two key strategic points that, if occupied by Union forces, would result probably in the collapse of the Confederate war effort—for, if these places fell, there would be nothing left for the Confederate Government to defend but its country's heartland. A heartland that could easily be reached if Virginia was knocked out of the war.

I

The Origin And Object Of The War

II

The War In The West

The Hornets Nest

Union Control Of The Mississippi River

Papers of Ulysses s Grant

III

The War in the East

General McClellan Progression

| Read all the Civil War Sesquicentennial articles | Comments and Questions to the Author |

|

Joe Ryan Original Works @ AmericanCivilWar.com Joe Ryan Video Battlewalks |

|

| About the author: Joe Ryan is a Los Angeles trial lawyer who has traveled the route of the Army of Northern Virginia, from Richmond to Gettysburg, several times. |

||

Battle of Gettysburg

General Robert E. Lee

General JEB Stuart

General Jubal Early

Confederate Commanders

General Joseph Hooker

Union Generals

American Civil War Exhibits

State Battle Maps

Civil War Timeline

Women in the Civil War