| Read all the Civil War Sesquicentennial articles | Comments and Questions to the Author |

| The War in the West The Hornets Nest Papers of Ulysses S Grant |

Union Control Of The Mississippi River

Opening the Mississippi River

April 1862—July 1863

I

Farragut Captures New Orleans

Up to April 1862, the governors of the Gulf States insisted on keeping a substantial number of their state troops garrisoned along the coast, the intent being to prevent the enemy from using the river system to penetrate into their respective states. But the physical power of the United States Navy quickly proved too much for these troops to handle. On the east coast, combined army and navy operations had established landings in North and South Carolina, and on the Georgia sea coast in front of Savannah. Landings had been made on the Florida gulf coast, and U.S. Navy gun boats were prowling the nag viable rivers along the Alabama coast. At the same time Captain David G. Farragut, commanding the West Gulf Blockading Squadron, was gathering together an armada of vessels to capture New Orleans.

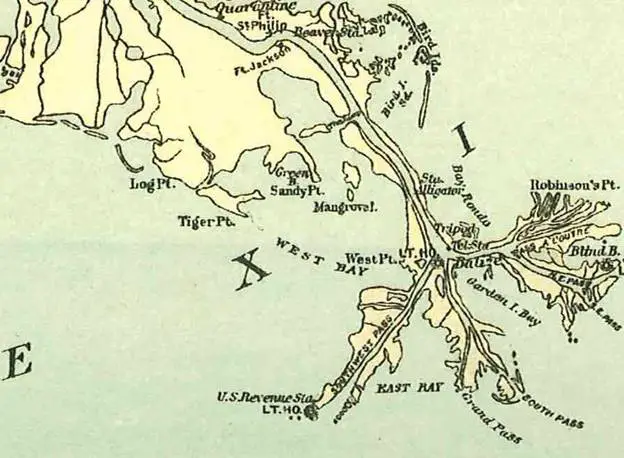

As the battle of Shiloh was being fought in Tennessee, Farragut's fleet, composed of ten ships of the line carrying, combined ,120 guns, along with a fleet of mortar boats, under the command of David D. Porter, and seven steamers, crossed the bar at the mouth of the Mississippi River and sailed upstream to Forts Jackson and St. Philip.

Foregut's fleet used the Southwest Passage to gain the channel

Confederate Defenses at the mouth of the river

The two

Confederate star forts were constructed of masonry, some of the walls being

seven feet thick. The armaments consisted of a total of 130 pieces of various

caliber mounted in barbettes or in casement. Each of the forts was garrisoned

with about 700 men. On the downstream side of the forts there were eight hulks

moored in line across the river, with heavy chain extending from one to the

other. Rafts of logs were also moored in the channel. The raft was fitted to

act as a gate, opening and closing as the defenders required. Besides the land defenses,

a fleet of heavy tugs and merchant vessels had been converted to armed vessels,

and there were two iron clad rams, the Manassas and Louisiana. The Louisiana, armor-plated with enough strength to

turn any shell the U.S. Navy ships could throw, carried sixteen heavy guns and

a crew of 200. However she did not have self propulsion, the two screw engines

designed for her not having been installed. In addition to these, there were

several gunboats and steamers in the Confederate fleet. The total guns

available from this collection of vessels were 35.

The two

Confederate star forts were constructed of masonry, some of the walls being

seven feet thick. The armaments consisted of a total of 130 pieces of various

caliber mounted in barbettes or in casement. Each of the forts was garrisoned

with about 700 men. On the downstream side of the forts there were eight hulks

moored in line across the river, with heavy chain extending from one to the

other. Rafts of logs were also moored in the channel. The raft was fitted to

act as a gate, opening and closing as the defenders required. Besides the land defenses,

a fleet of heavy tugs and merchant vessels had been converted to armed vessels,

and there were two iron clad rams, the Manassas and Louisiana. The Louisiana, armor-plated with enough strength to

turn any shell the U.S. Navy ships could throw, carried sixteen heavy guns and

a crew of 200. However she did not have self propulsion, the two screw engines

designed for her not having been installed. In addition to these, there were

several gunboats and steamers in the Confederate fleet. The total guns

available from this collection of vessels were 35.

The bombardment commenced on April 16, against the front of Fort Jackson. The mortar fleet hung in the west channel of the river, at a distance of 3,000 yards and at a point completely screened from the fort by a thick growth of wood. Shells were thrown at the rate of one every five minutes from each of the Union vessels, in all 250 shells thrown every hour the bombardment continued. The bombardment continued for eight days, sending in about 2,800 shells in every 24 hours, or a total of 17,000. By the end of this time the Union crews were exhausted, one ship had sunk by its seams knocked apart by the concussions, and the others all severely racked.

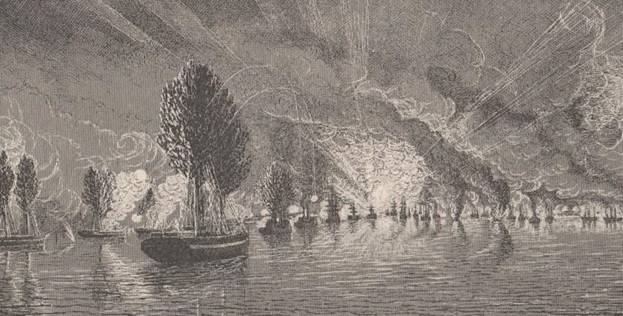

On April 23, Farragut ordered an attempt to pass the forts. At 2 a.m., the Union fleet advanced, the heavy ships proceeding first: Hartford, Brooklyn, Richmond, Pensacola, and Mississippi. The mortar steamers were to attack the rebel water batteries while the big ships passed the forts. Breaking through the chain obstructions, the ships came under heavy fire from the guns of Fort St. Philip and suffered much damage before they could bring their own guns into action.

Union Fleet, dressed with trees, attacking the forts

Above the forts the rebel gunboats were assembled, and several of them came into the main channel to challenge the Union ships but were driven off by the Union's superior fire power. The leading division moved up the river, engaging everything that confronted it, passing on. A Confederate colonel in Fort Jackson, watching the Union fleet in action, is supposed to have exclaimed to his fellows: "Better go for cover boys, our cake is all dough! The old Navy has won!"

As the fleet was passing, the ships were taking many hits from Fort St. Philip, but once they had all arrived in front of the fort in line and fired in unison, the rebel gunners were driven to shelter.

At about the same time, a rebel tugboat pushed a burning raft alongside the Hartford; the Hartford reacting, turned her helm to avoid it and ended up grounded in the shoals. The raft came against its side and fire raced up into the sheets, but Farragut's crew got the vessel off the shoal, pushed the raft away, put out the fire, and continued on toward New Orleans.

About noon on April 25. Farragut arrived at the levee of New Orleans as Confederate troops evacuated the place.

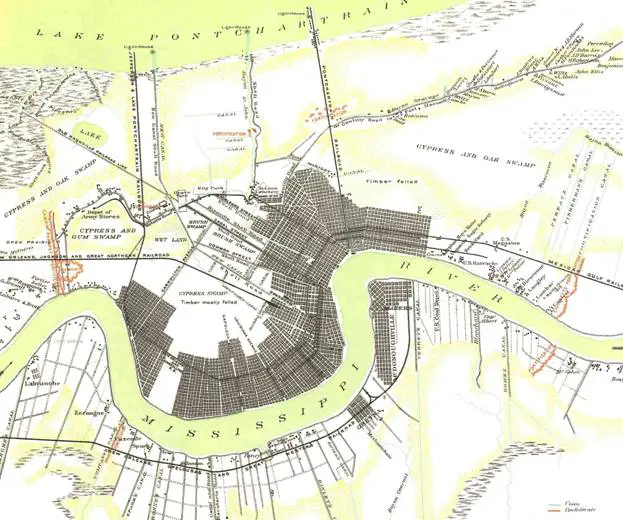

New Orleans

When Farragut arrived at New Orleans he found the city levee in flames. Steamboats were aflame in the slips; bales of cotton and piles of coal were a blaze lighting up the sky with a garish glow that reflected off the buildings of the town. When the ships dropped anchor in the channel thousands of people crowded the shore, shouting defiance. A few days later, Major-General Ben Butler arrived with ten thousand men to garrison the city.

II

The Attacks On Vicksburg

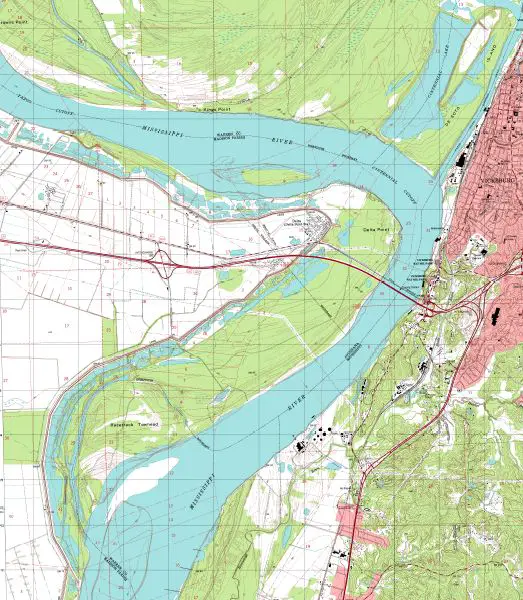

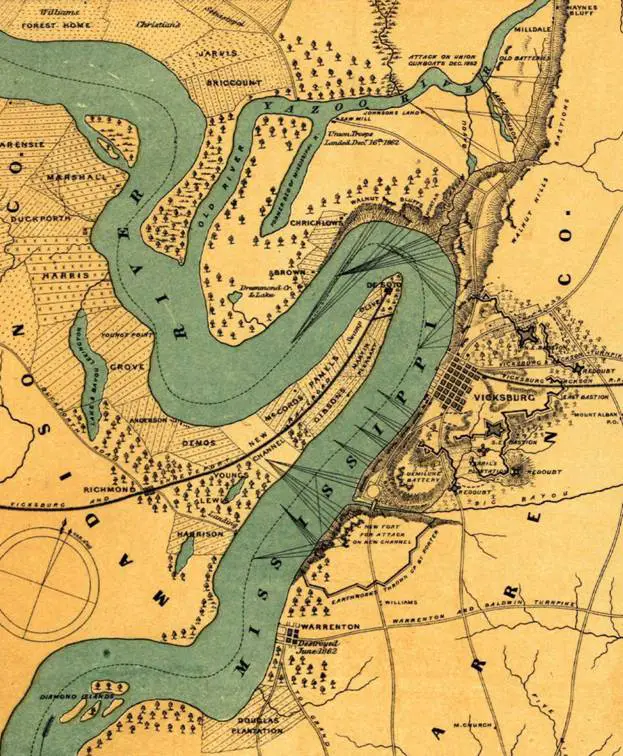

Farragut, without his mortar boats —they had been sent back to Pensacola for repairs―then steamed his war ships up river to Vicksburg. Here he stopped for twenty days and waited for the mortar boats to return. When they did, he commenced shelling the rebel batteries on the hills and as the shelling caused the gunners to take shelter, he passed his war ships to make a junction with Flag-Officer Davis who commanded the gun boat fleet that, with the capture of Memphis, came down the river to meet him.

Vicksburg

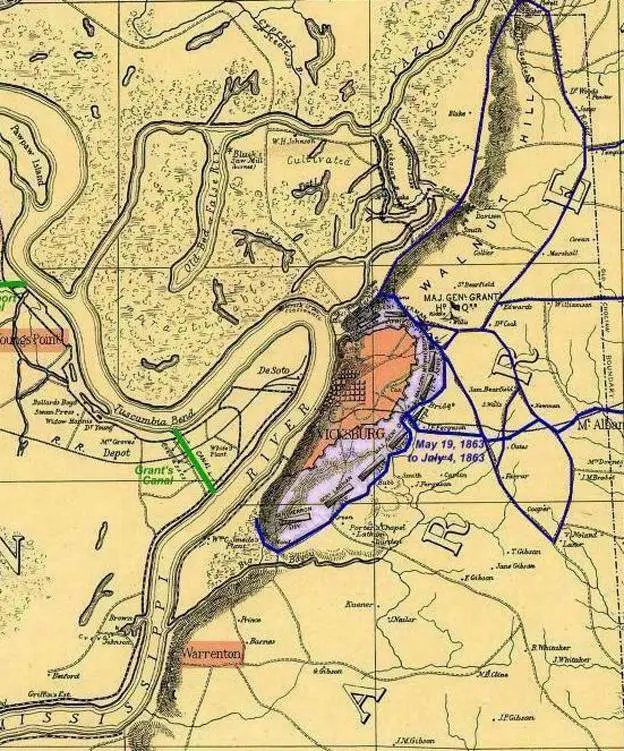

As Farragut and Davis were joining their fleets together, the Confederate Government was pouring troops and guns into Vicksburg. There was an area of 26 square miles within which the Union fleet could throw shells as they pleased, but the rebels ignored the falling shells and built up a vast network of entrenchments with gun emplacements that would require a Union army of three corps, struggling with the terrain for more than six months to overcome.

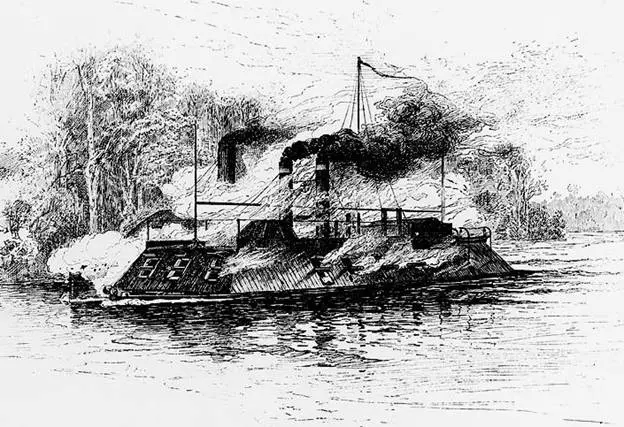

Learning that an iron clad was being built at Yazoo City, Farragut sent up that river the gunboats Carondelet and Taylor, in company with the ram Queen of West. Six miles from the river mouth these vessels met the iron-clad Arkansas. The iron plating of the Arkansas made her impervious to the shot and shell thrown at her by the Union vessels and the latter turned in the river and steamed back toward the Mississippi with the Arkansas throwing shells at them from her rifled guns. This running fight went on for an hour until the Arkansas came along the Carondelet and, with her iron prow, tried to ram her. The two vessels exchanged fire, the Carondelet losing her wheel ropes in the process and she sheered toward the shore as the Arkansas swept past. The Carondelet was much damaged in hull and machinery with thirteen shot holes in her hull, steam gauge, escape pipes, beams and timber shot away. Thirty men in the crew were killed or wounded.

Arkansas battling Carondelet

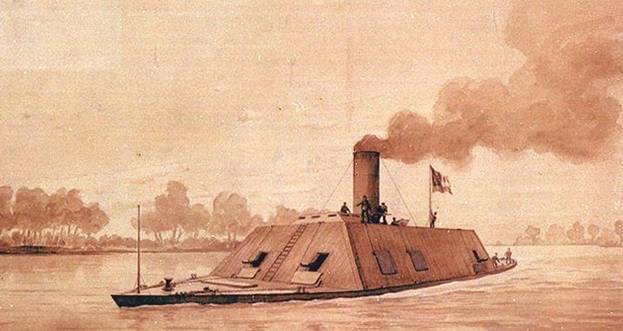

With the Carondelet out of the fight, the Arkansas steamed after the other two Union vessels that now were pushing as fast as their boilers would let them toward the Mississippi and the presumed safety of Farragut's fleet. But the boilers of Farragut's ships were on low fires and, when the Arkansas appeared in the Mississippi, they were unable to maneuver against her. Though she came under fire, she swept through the entire fleet, throwing shells into the wooden hulls of the Union ships, and got down under the rebel forts at Vicksburg. The rebel vessel was severely damaged in the fire fight. She had taken many hits and several shells from 11-inch guns had penetrated her sides, cutting her up inside, killing and wounding twenty of her crew. The Union gunboat Essex went down stream to engage the Arkansas but was much cut up by the rebel batteries and broke off.

The C.S.S. Arkansas

The next morning Farragut moved his fleet back down the river to protect his mortar boats and transports, each of his vessels firing into the Arkansas as they passed the forts. There was a shroud of mist hanging over the river at the time and the rebel batteries were returning fire, so little additional damage was done to the ram.

Farragut and Davis then conferred, coming to the conclusion that the defenses of Vicksburg could not be subdued by the Navy alone. They had demonstrated that naval war ships could transverse the bend of the river, coming up and going down, but only under such fire from the rebel batteries that serious damage could be done to them. In no event could civilian steamboats, or troop transports get past Vicksburg without absorbing substantial damage, always under threat of sinking. The two flag officers decided to return to their stations, Davis back up river to Memphis and Farragut down river to New Orleans. In October 1862, Davis was replaced with David D. Porter, previously the lieutenant who had carried out Lincoln's ruse with Charleston, in 1861, that started the war, and now a rear admiral.

Farragut left the Mississippi and took his fleet to the coast of Texas and blockaded Galveston. Farragut captured the place in October 1862, but the Confederates counterattacked, substantially destroyed his fleet and reoccupied the town.

D.D. Porter, Lincoln used him to start the war

The plan, if there was one, of sending an army of ten thousand men to take possession of Vicksburg was not carried out. Ben "The Beast" Butler refused to send them from New Orleans. The Union gun boat fleet was removed from the upper Mississippi and broken up. The river from Baton Rouge to Vicksburg was now abandoned to the Confederates and they went to work building forts and planting guns along its breath.

In October 1862, Farragut returned to the Mississippi and, in conjunction with Porter's upper Mississippi fleet, and the cooperation of the army, again attempted to attack Vicksburg. At this time the war in the west had degenerated into guerillas warfare, with rebel bands on the shore firing into any vessel on the river. No commerce was allowed on the river, except with Memphis. Lincoln assigned McClernand, one of the Illinois crowd who had fought a division at Shiloh, the task of raising troops in Illinois and using them to lay siege to Vicksburg.

At this time Grant was standing at a point on the Mobile & Ohio Railroad called Holly Springs, guarding the approach to Corinth and Memphis while Buell was moving toward Chattanooga on the Memphis & Charleston Railroad. Grant authorized Sherman, who was occupying Memphis, to move on Vicksburg.

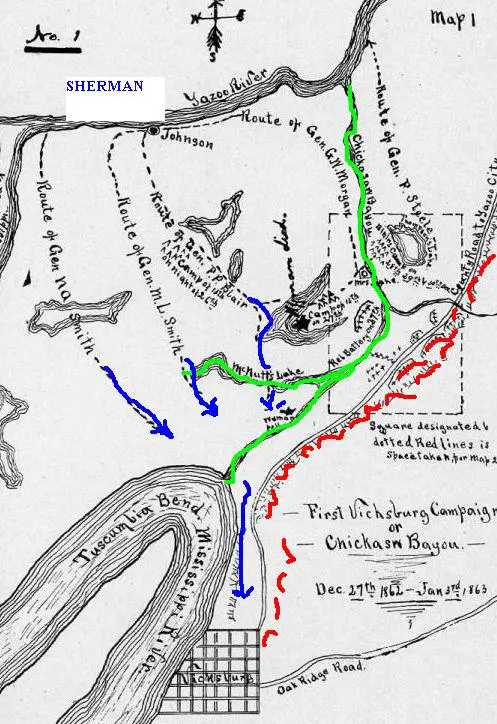

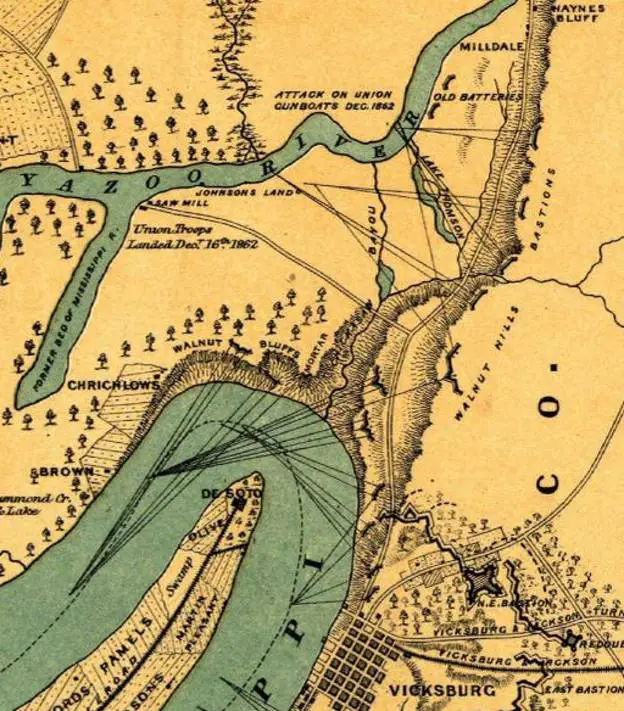

In December 1862, Sherman, using transports, moved his army corps to a point on the Mississippi called Chickasaw Bayou, the landing covered by Farragut's gunboats. Sherman tried to advance toward Vicksburg but the heavy rains filled the bayous, forcing him to build causeways which were killing work. Vicksburg now was fortified at every point, and its only approaches by land led through dense swamps or over boggy open ground, where heavy guns had been placed to mow down an approaching army. Despite these obstacles Sherman eventually pushed his army up to the bluffs.

As Sherman was in the process of gaining a foothold at the base of the Vicksburg bluffs, Grant had moved his Army of Tennessee south from Holly Springs toward Jackson, in a ploy to draw the rebel garrison away from Vicksburg to defend Jackson. But as Grant moved, the rebel general, Van Dorn, came into Grant's rear and swept into Holly Springs, 28 miles now in Grant's rear, capturing the garrison and the immense stockpile of supplies that constituted Grant's base of operations. At the same time rebel cavalry, under Forrest, pushed into west Tennessee, cutting the Mobile & Ohio Railroad at several points between Columbus, Kentucky and Jackson, Tennessee. This completely cut Grant off from his only line of communication with the North, either through Memphis or Nashville, and he was forced to draw back and reclaim his base at Holly Springs.

As Grant was falling back, Sherman, on December 29, 1862, attacked the batteries on the bluffs but was driven back by the Confederate troops who had just returned to their stations after moving north to confront Grant's aborted advance. There was nothing left for Sherman to do by get back to the transports and return to Memphis.

Sherman's Approach to Vicksburg, December 1862

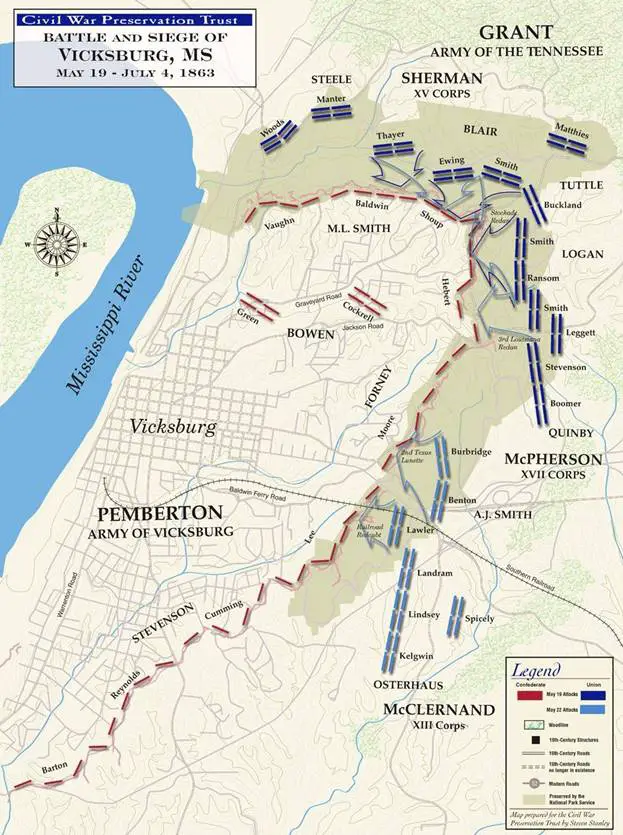

After capturing Arkansas Post, in January 1863, Sherman moved his army to Young's Point and Milliken's Bend, points located about six miles above Vicksburg and there he went into camp and waited for Grant to arrive. Vicksburg was now garrisoned with 40,000 troops under Pemberton and Joe Johnston was holding Jackson with 40,000 more men. It would take Grant six months to capture Vicksburg.

Grant, The Soldier

Something

ought to be said here about Grant the soldier. As earlier pieces have shown

Grant gained his position as commander of the armies of the West through the

support given him at the beginning of his war-time career by John Pope and the Illinois crowd of politicians that swarmed around Lincoln.

Something

ought to be said here about Grant the soldier. As earlier pieces have shown

Grant gained his position as commander of the armies of the West through the

support given him at the beginning of his war-time career by John Pope and the Illinois crowd of politicians that swarmed around Lincoln.

By the time Henry Halleck came on the scene as commander of the Department of Missouri, Grant had been placed by Fremont in command of the sector of southeastern Missouri, with headquarters at Cairo, Illinois. The evidence is plain that, on a personal, as well as a professional level, Henry Halleck did not like Grant, attempting by various means to supplant Grant with other officers. For various reasons these schemes failed and Grant remained in the position of Halleck's immediate subordinate until he took Halleck's place when Halleck was called to the East by Lincoln, in July 1862.

If viewed solely from the point of view of professional competence in the management of an army's movement in the field, Grant gets a very poor grade; his demerit being that he consistently underestimated the ability and willingness of the enemy to take the initiative against him.

The record shows the proof of this. At Fort Donelson, Grant left the front of his army at a time when the fort's garrison was poised to strike a blow. Giving his division commanders orders not to bring on a general engagement, Grant left the front to go several miles downstream to meet with Navy officer Foote, to talk about logistics. In his absence, Gideon Pillow led the garrison out of the fort and attacked McClernand's division, driving it back from the river road about two miles. But for the fact that Halleck had pushed thousands of men up the Cumberland River, to reinforce Grant, Pillow's attack might well have resulted in Grant's force being driven back across the peninsula to Fort Henry. At Shiloh, again Grant was not present with his army in the field when the enemy attacked, though Grant well knew for several days that Sidney Johnston's entire army was in close proximity to the Union camps at Shiloh.

In December 1862, Grant no sooner moved his army south toward Vicksburg to help Sherman in his effort to capture Vicksburg than he was forced to turn around in order to regain his base of operations at Holly Springs, having lost it to Confederate general, Earl Van Dorn, who, with 3,500 cavalrymen, had ridden around his left flank and, brushing aside the infantry brigade Grant had left as guard, destroyed a vast conglomeration of warehouses, filled with commissary, quartermaster, and ordnance stores, plus machine shops, wagon yards, an armory and a foundry. Van Dorn's raid resulted in the destruction of millions of dollars of equipment and supplies, enough to have supplied a field army for months.

But these observations are just paper criticisms. What was the reality of the matter? What explains Grant's conduct, lacking as it clearly does the polish of West Point professionalism? The answer must lie in Grant's certain knowledge, his unshakable conviction that his side of the line possessed the advantage of brute force, of manpower— that the Union had such an overwhelming advantage of manpower, that a reverse was only a momentary event, to be immediately corrected by the application of an endless supply of bodies that could instantly be thrown into the struggle to, first, stabilize the tactical situation, and, then, force the enemy to not only give up the field but give up huge chunks of strategic territory in retreat. With this mindset, Grant appeared to be cavalier but in fact he was being cold-blooded; he was inviting the enemy to attack him because he was certain that when the butcher's bill was added up, the enemy's account would be so depleted, the loss could not be made up. Grant's His mind-set reduces simply to an absolute belief that the Union will win the war by attrition.

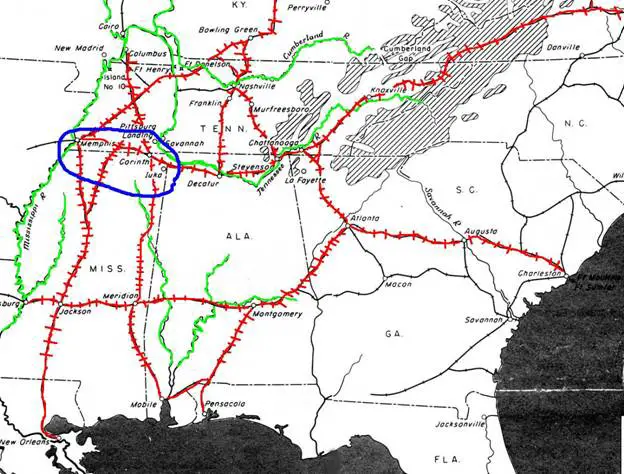

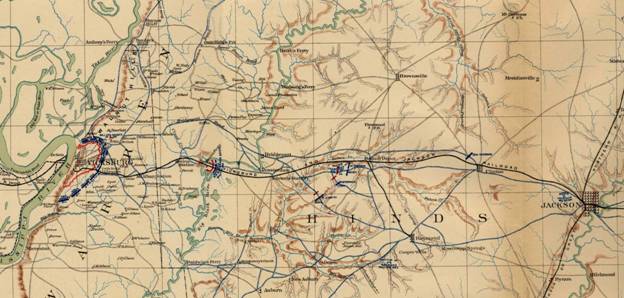

The Confederate Railroad Net in the West

By December 1862, the war from a purely strategic point of view was practically over. From the beginning, Abraham Lincoln expressed the view that Kentucky was the key to victory, that with Kentucky he was certain the Union would win, without Kentucky he was afraid the Union would lose. Lincoln was successful in holding Kentucky in the Union and the result was the loss of Tennessee and Missouri to the Confederacy, with the northern sectors of Mississippi and Alabama occupied by Grant's armies. This left the Confederacy with one railroad linking the west to the east, that from Vicksburg through Jackson, Meridian, and Montgomery to Atlanta and then to Knoxville and Charleston. It also left the Union with only two strategic points necessary to capture before the war in the West was at a certain end—Vicksburg and Chattanooga, the gateway to Atlanta the heart of the Confederacy. To accomplish the capture of these places, though, the advantage of overwhelming manpower was not enough.

The war, by December 1862, had become a simple matter of logistics. It is 167 miles from Cairo, Illinois, to Memphis, Tennessee, and 250 miles from Memphis to Vicksburg—a line of supply of 417 miles. It is 269 miles as the crow flies between Memphis and Chattanooga and 134 miles from Nashville to Chattanooga. The four railroads that connected Cairo to Memphis and Memphis and Nashville to Chattanooga were now under Union control. These are the Mobile & Ohio Railroad (connecting to the Mississippi Central Railroad), the Memphis & Charleston Railroad, the Nashville & Decatur Railroad and the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad. In order to move his armies to the objectives of Vicksburg and Chattanooga, Grant had to rely completely on these railroads to carry the thousands of tons of supplies the field armies consumed on a daily basis. From Cairo, Illinois, and Paducah, Kentucky, supplies had to move down the railroads to points farther south where supplies could be stockpiled in a string of depots, the string advancing south as the armies advanced. (The Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers could also be used for this purpose, but in the summer months they were too shallow to handle the drafts of steamboats.) This fact―Grant's armies could not operate without the uninterrupted use of railroads—became the linch-pin of Confederate military strategy in the West.

For Grant's part, consistent with his mind-set of overbearing confidence in Union power, he accepted this fact as a reality he could do nothing about. He had begun his wartime career operating, under John Pope's command, in Northern Missouri. As a colonel of an Illinois regiment, and, then, as a brigadier-general, his function had been to deploy the forces under his command in such a manner as to protect the railroad between St. Joseph and Hannibal, Missouri; then, to protect the railroad between St. Louis and Ironton, Missouri. The residents in the Missouri counties within the sectors he operated in, were, for the most part, Confederate in sympathy, and they quickly adopted the classic tactics of guerilla warfare; hit and run attacks against the railroads―destroying rails and switches, burning bridges and culverts—became a daily event. Grant combated this warfare the only way it can be combated. He spread what troops were available to him along the railroad, a regiment covering so many miles of track, with a reserve available as a quick response force to travel to a hot spot by train. Guards were placed at all bridges and switch points. Still, the effort failed in Missouri and Grant, through his superior Pope, turned to the practice of retribution against the ostensible civilian population, burning their farmhouses and destroying their livestock and, in some cases, murdering them, as a means to counter terror with terror.

The

magnitude of the guerilla warfare problem was multiplied many times by the vast

railroad network Grant had to protect in order to maintain his armies in the

field in operations against Vicksburg and Chattanooga. The mileage of track to

be protected was so large that it was simply impossible for Grant to detach the

amount of troops required to actually protect all points in the system. So, in

large measure, as shown by the fact he suffered the professional embarrassment

of losing his base of operations to the enemy, Grant simply ignored the

problem, pushing on despite the threat of interruptions, relying instead upon

clearing the problem, reestablishing the line of supply, and moving on.

The

magnitude of the guerilla warfare problem was multiplied many times by the vast

railroad network Grant had to protect in order to maintain his armies in the

field in operations against Vicksburg and Chattanooga. The mileage of track to

be protected was so large that it was simply impossible for Grant to detach the

amount of troops required to actually protect all points in the system. So, in

large measure, as shown by the fact he suffered the professional embarrassment

of losing his base of operations to the enemy, Grant simply ignored the

problem, pushing on despite the threat of interruptions, relying instead upon

clearing the problem, reestablishing the line of supply, and moving on.

It was, consequently, a stop and go process, because the Confederates took full advantage of the strategic dilemma Grant was operating under, through the outstanding performance of their cavalry commanders. In addition to Van Dorn's capture of Grant's base at Holly Springs, Bedford Forrest and John Morgan repeatedly swept through Tennessee and Kentucky, Morgan at one point even crossing the Ohio River, raiding Union depots and destroying bridges and long stretches of railroad. In July, 1862, for example, Forrest, with 1,500 troopers, captured Murfreesboro, Tennessee, with its entire garrison, a brigade of infantry and cavalry and its commander, Brigadier-General T.T. Crittenden. Grant was forced to suspend his movements south into Mississippi and divert troops to Tennessee, to protect the railroads and to drive Forrest back into Alabama.

Forest Rides

This is a process that repeated itself many times in the remaining years of the war. In 1862, Forrest attacked depots at Hopkinsville, Fort Henry, Nashville, Brentwood, and Franklin. In 1863, he traversed West Tennessee and passed through Kentucky as far as the Ohio River at Paducah, at one point entering Memphis. In 1864, he repeated this performance, fighting pitched battles at Brice's Crossroads and at Fort Pillow where he is accused of slaughtering the defending Negro troops. (Grant's use of Negro troops to man the back areas demonstrates that the Union was straining to maximize the use of its manpower to cover as much territory as possible.) The only reason it took the Union from April 1862 to September 1863, to capture Chattanooga was the challenge of keeping the railroad between Nashville and Chattanooga in operation.

And, of course, the delay in capturing Chattanooga meant that the Confederacy's strategic base of operations―Atlanta, Georgia—remained secure into 1864. That Atlanta was ultimately the key to Confederate survival the record makes clear.

Atlanta, May 1, 1862

Confederate Secretary of War

The State has placed all her means of defense in the hands of the President. The enemy are near Chattanooga. If it is taken, the railroad bridges on both sides of it burned, we are cut off from the coal mines, and all our iron mills and machine shops are stopped. We are soon to be driven out of Tennessee, it seems, and both armies fed on what little provision is left in the cotton regions. It cannot last long. Our wheat crop is ruined with rust, and all our young men not now under arms called from their fields by the conscription act, when you have not arms for them.

I express but the universal sentiment of our people when I say that the defensive policy of fortifying and falling back toward the center will, if persisted in, end in starvation and overthrow.

JOSEPH E. BROWN, Governor of Georgia

Richmond, May 2, 1862

Gov. Brown:

I concur with you as to the importance of Chattanooga. Your dispatch indicates a willingness to withdraw your former objection to the transfer of troops from the sea coast of Georgia. If a brigade can be spared from there, General Pemberton will be directed to send it to Chattanooga.

JEFFERSON DAVIS

Headquarters, Richmond, May 2, 1862

Maj. Gen. Kirby Smith, commanding Knoxville

General: Everything in my power has been done for your assistance, and I only regret that I could not do more. A regiment of infantry and one of cavalry from Georgia has been ordered to Chattanooga to your support. I have applied to the governor of Alabama to send you troops and the Indian regiment from North Carolina has been sent to you.

I am your obedient servant, R.E. LEE, general commanding

Headquarters, Corinth, May 1862

General S. Cooper, Adjutant-General Richmond:

I give the reasons why I still hold this place instead of retiring into the interior. Corinth, situated at the intersection of two railroads, presents the advantage of possessing these tow main arteries for the supplies of a large army. By its abandonment only one of those roads could then be relied upon for this object. If the enemy took possession of this point, he would at once open his communications by railroad with Columbus and Paducah in his rear and Huntsville on his left flank, and thus relieve himself of the awkward position in which he is about to find himself by the rapid fall of the Tennessee River.

It is also evident that the true line of retreat of the forces at this point is along the Mobile & Ohio Railroad toward Meridian and thence toward Montgomery, so as to be able, as a last resort, to unite with the armies of the East.

The fall of Vicksburg would endanger our lines of communication with Meridian, Montgomery, and Selma and we would be compelled soon to abandon the whole State of Mississippi and another large portion of Alabama, to take refuge behind the Alabama River. Cut off from communication with the East Mississippi could no longer support our army. Thus it becomes essential, if we can, to hold Corinth to the last extremity.

G.T. Beauregard, General commanding

HEADQUARTERS, RICHMOND, May 26, 1862

General G. T. Beauregard;

The condition and movements of your army have been the subject of anxious consideration. Full reliance is felt in your judgment and skill and in the bravery of your army to maintain the great interests of the country and to advance the general policy of the government. It was hoped that the victory of Shiloh would have enabled you to upon the arrival of your reinforcements (Van Dorn's 17,000 troops arriving from Arkansas) to occupy the country north of you and to have reestablished the former communications enjoyed by the army. This hope is still indulged.

Should, however, the superior numbers of the enemy force you back, the line of retreat indicated by you is considered the best and in that event it is hoped you can strike an effective blow at the enemy if he follows, which will enable you to gain the advantage and drive him back to the Ohio. (Boy, is this wishful thinking?)

The maintenance of your present position is of course preferable to withdrawing from it, and thus laying open more of the country to the enemy's ravages.

The supplies accumulated at Atlanta are intended as a reserve for the army in the East as well as the West, and cannot be entirely appropriated to either division. Each army must therefore draw its support, as far as possible, from the country it can control, and this necessity must not be lost sight of in the operations of either, and any accelerate movements which otherwise it might be deemed prudent to restrain.

I am, respectfully, your obedient servant, R.E. LEE, General.

From the day Corinth was abandoned by Beauregard's army the Civil War was effectively over, the winner certain. Grant must certainly have understood this essential fact and it motivated him in every action he took thereafter, patiently pressing his armies forward, shuffling off the irritations imposed on his advances by Confederate guerilla warfare, in time bringing his armies to battle at Vicksburg, Chattanooga, and Atlanta; and then going East to press Lee back to Petersburg. The butcher's bills were high but the battles were won, the Union preserved sort of, and out of it Grant made himself President.

Grant's First Effort at Vicksburg Was a Failure

Grant's Second Effort, Crossing the River South of Vicksburg, Succeeded

Vicksburg Defenses, Walnut Hills

Vicksburg Defenses Looking East

Grant Finally Breaks In, July 4, 1863

Congressman Washburne Stands up for Grant in the House

May 2, 1862

I come before the House to do a great act of justice to a soldier in the field and to vindicate him from the verbal abuse so persistently and cruelly thrust upon a distinguished soldier who has recently fought the bloodiest and hardest battle ever fought on this continent, and won one of the most brilliant victories. I refer to the battle of Pittsburg Landing and to Major-General Ulysses S. Grant.

There is a grievous suggestion touching the general's habits. It is a suggestion that has infused itself in the public mind everywhere. It is a slander. He never indulges in the use of liquor at all.

Let not gentlemen have any fears of General Grant. He is no candidate for the Presidency. He is no politician. When the war shall be over he shall return to his home and be a simple citizen.

But to the victory of Pittsburg Landing which has called forth such a flood of denunciation upon General Grant. When we consider the charges of bad generalship, incompetency, and surprise, do we not feel that even the joy of the people is cruel? I will not argue the issue of surprise; but even it there was surprise, General Grant is in no way responsible for it, for he was not surprised. He was at his headquarters at Savannah when the fight commenced. That was the proper place for him to be at that time.

The attack was made Sunday morning by a vastly superior force. In five minutes after the first firing was heard Grant was on his boat going to the scene. I have a letter from one of his aides that say he arrived there at 8:00 a.m. and immediately assumed command.

What glory! Our troops, less than 40,000, attacked by 80,000!

Grant is criticized for putting his army on the west side of the Tennessee River. I suppose the critics would allow the rebels to entrench on the west side and then have our army cross the river in their face. It was, in the judgment of the wisest military men, a wise disposition of his forces to do as he did.

After fighting all day the enemy drove our forces only two and a half miles, and then they had to face the batteries and gunboats that General Grant so skillfully arranged. And when night came the army stood substantially triumphant on that bloody field.

No Illinois regiment, no Illinois company, no Illinois soldier, fled from the battle field. If any did flee they were not from Illinois.

Mr. Cox interrupts: "I had no idea that you would attack the valor of soldiers from my State!."

Mr. Washburne: I did not make any such attack. I did not say anything against Ohio troops.

Mr. Cox: I want to say to you that there were twenty-four Ohio regiments in that battle. An Illinois newspaperman has slandered Ohio by claiming Ohio soldiers ran. This is a lie.

Mr. Washburne: I am very glad to hear it, though it is a fact that the most outrageous attacks upon Grant have come from Ohio papers. (laughter)

Now, sir, I have a little more to say. I have a word to say about McClernand who rode at the head of his division, holding his flag in the face of the enemy; Hurlbut, from my own district, commanded another division with great glory, and Prentiss fought most gallantly with his division, and Wallace from my State, who fell nobly fighting at the head of his division, whose memory will be forever honored by Illinois

Mr. Wilson: I ask the gentleman whether he denies that the army was surprised at Pittsburg on the morning of Sunday?

Mr. Washburne: I deny that charge. But I need not argue the issue, because it is not necessary to General Grant's defense. I say that whether there was or was not surprise at Pittsburg Landing, the manner in which all those gallant troops fought on that day has conferred upon them and upon the country imperishable renown.

Mr. Wilson: I ask, admitting that it was a surprise, whose fault was it?

Mr. Washburne: I suppose if there had been any surprise it would be the fault of the man who commanded the division surprised.

Mr. Kellogg, of Illinois: I want to say my colleague has defended his friend well. I regret the disposition to find fault with our generals in the field. Let us remember only their prowess and their glory and forget the recriminations.

Mr. Wilson: I concur that this matter ought not to have been brought up here. I have thought the whole thing out of taste. No charge has been made here against General Grant, although there are very grave differences of opinion in relation to certain matters connected with the fight.

Mr. Washburne: I say that despite the partial repulse of Sunday, our troops, aided by the fresh division of Lew Wallace, the army could have whipped the enemy on Monday without help from anyone else. The final charge of General Grant at the head of his reserves will have a place in history. While watching the progress of the battle on Monday afternoon, word came to him that the enemy was faltering on the left. With the genius which belongs only to the true military man, he saw that the time for the final blow had come. In quick words, he said: "Now is the time to drive them." It was worthy the world-renowned order of Wellington, "Up, Guards, and at them!" Then riding out in front amid a storm of bullets, he led the charge in person, and Beauregard was driven, howling, to his entrenchments. His left was broken and the retreat commenced. The loss to the enemy was three for our two. The battle has laid the foundation for driving the enemy from the Southwest.

Comment

After Shiloh, did Grant ever command tactically a battle again?

Joe Ryan

I

The Origin And Object Of The War

II

The War In The West

The Hornets Nest

Union Control Of The Mississippi River

Papers of Ulysses s Grant

III

The War in the East

General McClellan Progression

| Read all the Civil War Sesquicentennial articles | Comments and Questions to the Author |

|

Joe Ryan Original Works @ AmericanCivilWar.com Joe Ryan Video Battlewalks |

|

| About the author: Joe Ryan is a Los Angeles trial lawyer who has traveled the route of the Army of Northern Virginia, from Richmond to Gettysburg, several times. |

||

Battle of Gettysburg

General Robert E. Lee

General JEB Stuart

General Jubal Early

Confederate Commanders

General Joseph Hooker

Union Generals

American Civil War Exhibits

State Battle Maps

Civil War Timeline

Women in the Civil War