| Read all the Civil War Sesquicentennial articles | Comments and Questions to the Author |

What Happened in April 1862 ©

I

The Origin And Object Of The War

| The War in the West The Hornets Nest Union Control of the Mississippi Papers of Ulysses S Grant The War in the East General McClellan Progression |

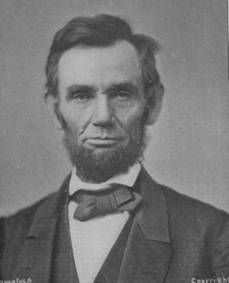

Editor's Note: State departments of education and, consequently, text book writers, have constructed a false impression over the last one hundred years, of what exactly caused the American Civil War. Invoking a chain of abstractions, they present the cause of the war as a series of economic and political events that induced the North and the South to engage in violent conflict. Resentments over governmental policies of tariffs, taxes, and immigration into the territories, coupled with the splintering of the Democratic Party into factions, they teach, essentially constitute the sum of the complex causes of the Civil War. Yet, the evidence they ignore shows indisputedly that the real cause of the Civil War was simply white racism, a deep virulent prejudice by all but a very few of the white people that inhabited the States both north and south of the Mason-Dixon Line, in 1861.

Nowhere in the textbooks these educators provide, can the intelligent high school or college student find the objective truth of history. As a consequence americancivilwar.com offers those students interested in understanding what was really at the bottom of the war this abridged version, transcribed verbatim in all essential parts, of the Congressional Record of the Second Session of the Thirty-Seventh Congress of the United States, as printed by the court reporter, John Rives, in 1862.

Joe Ryan

In The United States Senate—Slavery In The District

April 1, 1862

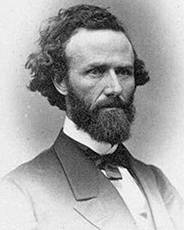

Mr. Wright, of Indiana: Mr. President, I earnestly hoped that when I took my seat here, I would be able to do something that would tend to the putting down of this rebellion; and I had hoped that these embarrassing questions which have disturbed our country for years would at least not be presented in the present unfortunate condition of our country.

I have no tastes which would be gratified by going back to the past. I leave it to other senators to speak of the history of the organization of the Government of our fathers. I know that your fathers and mine had trouble in forming the principles of this Government. This evil which we now have in our land was then among us. And I apprehend that our fathers did the best they could under the circumstances.

What do I find here? Instead of senators avoiding questions which are calculated to enlist the bitterest feelings, bill after bill is presented which is calculated to inflame and irritate and cause sectional discord; and my purpose is today to give my reasons for the votes I will give on them. I am no apologist for slavery. I am opposed to it. But I cannot vote for this bill abolishing slavery in the District.

My reason is that the Senate has decided against the principle of colonization. In Indiana we have settled this question explicitly and firmly by constitutional provision. Illinois is doing it. Ohio will do it. We tell you that the black population shall not mingle with the white population in our States. We tell you that in your zeal for emancipation you must ingraft colonization upon your measure. We intend that our children shall be raised where their equals are; and not in a population partly white and partly black; and we know that equality never can exist between the two races.

The State of Illinois has just ingrafted a provision into its constitution, in these words:

"Sec 1. No negro shall migrate or settle in this State after the adoption of this constitution.

Sec. 2. No negro shall have the right of suffrage, or hold any office in this State."

We in the Northwest feel the force of the idea that was alluded to by my friend from Wisconsin, Mr. Doolittle, when he said that one sixth of all the population in his town was likely to be black, if they took their share of the negroes if emancipation goes through. Thus do we understand the matter; and we do not intend to allow our region of the country to be overrun with the black race. Such is the prejudice, such is the settled conviction of our people, that the wall which we have erected is to stand. We intend to have in our State as far as possible, a white population, and we do not intend to have our jails and penitentiaries filled with the free blacks.

In this connection I allude to the message from the President which proposes that we resolve to inform the slave States that Congress will provide financial help to them if they emancipate their slaves. As far as I know this is the first effort in the history of this country where the Government of the United States has ever proposed to a sovereign State of this Union anything connected with her domestic policy. I remember reading of a distinguished gentleman who, having crossed over the Potomac, and looking at the army of one hundred thousand glittering bayonets, and then looking back at the Capitol, exclaimed: `this is the last of this Government. State lines will be blotted out.' This may be so, but never by my vote.

The Senator from Massachusetts yesterday repeated the sentiment that 'freedom is national, slavery is sectional.' But there is another sentiment—the Constitution is national, and the right of the people of the States to make their own domestic policy is national." The proposition of the President is at variance with all my recognized notions of State rights.

Note: Here is highlighted the essential political fact that what the people of the United States did by civil war was to strip this right from the constitution, transferring the right from the people of the States to the people of the United States, in Congress assembled. Today, one hundred and fifty years later, almost a third, if not half, of the voters seem to desperately wish this right to come back to the States. The wish lies just beneath the surface of the debates over abortion, gay marriage, illegal immigrants, gun and drug control, and other equally unsettling political issues. The question, thus, in our time, recurs: do we as a people want each State to be in exclusive control of its domestic policy, or do we want the Federal Government to impose upon the States collectively one domestic policy. Surely the American Civil War teaches us the answer.

Mr. Jefferson, as early as 1809, was concerned that the Federal Government might swallow up the States. If Mr. Jefferson said that, then, I do not know what he would say now when the House has passed a resolution, suggested by the President, telling the people of a certain section of the country, on a subject of their domestic policy, `do this, and we will do that.' I am for the old-fashioned State rights doctrine. I mean that each State has a right to regulate its domestic policy, including all the social relations and the internal government of the State, and that the national Government has no right to interfere. As Jefferson said, so do I: `The true theory of our Constitution is that the States are independent as to everything within themselves, and united as to everything respecting foreign nations. (Jefferson's Works, Vol 4., p. 331.)'

Note: An obvious attribute of the change caused by the Civil War is seen in the fact that Congress, almost daily, passes laws now which transfer funds to the States for their use, if but only if the States modify their domestic policies as the Congress specifies. Congress, in effect, says, "Do this, and we will do that."

It is my conviction that in ninety days from now, if this Congress will attend to what appropriately belongs to it in this hour, we can have peace in every county in Tennessee, and in ninety days more we may have a Governor in every one of the slaveholding States. If Congress stands by and leaves the Constitution as it is, and leaves the institution of slavery to take care of itself, we shall put down this rebellion.

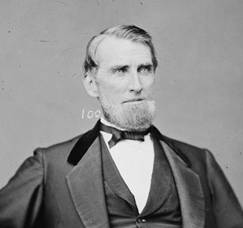

Mr. Pomeroy of Kansas: I do not wish to vote compensation to slaveholders here in the district. I do not believe we have the right to give away a million dollars from the Treasury for this purpose. The holders of slaves here are running out every day. I live in a State where slavery was abolished at once, on the 29th of March last year, at midnight, every slave in our State passed from a condition of slavery to freedom. They all went to bed slaves, if, indeed, they had any beds, and in the morning they got up and walked about, freemen. I have not seen any trouble arising from that.

Note: Mr. Pomeroy, a Radical Republican, a bit corrupt and in the pocket of the railroads, is ignoring the 5th Amendment to the Constitution which specifies that no person may be deprived of property without due process of law and with "just compensation." Or perhaps not.

Mr. Sumner of Massachusetts: How many were there, I should like to ask the senator?

Mr.

Pomeroy: I am unable to say exactly. I suppose there were some

hundreds. If we are to give compensation, I say we settle the account

between master and slave with justice. The senator from Vermont, Mr. Collamer,

said that [in In Re Dred Scott (1856)] the Supreme Court had

decided that negroes had no rights that white men were bound to respect. Does

the Senate intend to enact that decision of the court? By giving compensation

to the slaveholders and dealing out not one dime to the men who have spent

their lives in slavery and rendered labor which has been unpaid for, I say that

is reenacting the dogma that negroes have no rights that white men are bound to

respect.

Mr.

Pomeroy: I am unable to say exactly. I suppose there were some

hundreds. If we are to give compensation, I say we settle the account

between master and slave with justice. The senator from Vermont, Mr. Collamer,

said that [in In Re Dred Scott (1856)] the Supreme Court had

decided that negroes had no rights that white men were bound to respect. Does

the Senate intend to enact that decision of the court? By giving compensation

to the slaveholders and dealing out not one dime to the men who have spent

their lives in slavery and rendered labor which has been unpaid for, I say that

is reenacting the dogma that negroes have no rights that white men are bound to

respect.

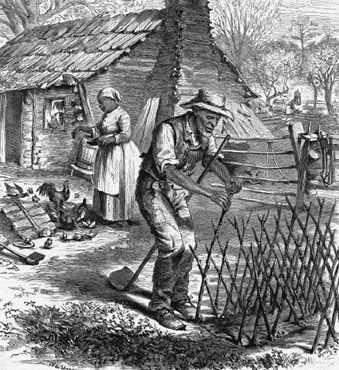

I call attention to the fact that there are men here who have spent forty years in slavery, and during all this time have never had anything more than was necessary to support them; and now, at an advanced age, this Senate proposes to turn them out without a dollar. I insist that we should weigh out justice to these parties.

Do gentlemen call upon us, because we are prosecuting this war, to forget all we have said, and all we have been struggling to accomplish for years? What, sir, have we been struggling for? It was to place this government in a position where it should not lend its aid to the support of slavery. Since its formation it has been devoted to that object; and what the Republican party contended for was to free the Government from the incubus that had been laid upon it through its unnatural connection with this peculiar institution.

Now, sir, are gentlemen so unreasonable as to ask us that we shall forget all we have tried to attain; that we shall ignore the question of slavery? You are asking too much of us, and the reasoning of the gentlemen who ask this is hardly a fair one. Let me ask the Senator from Virginia, Mr. Willey, does it follow that because we adopt one measure that we mean to adopt another? The honorable Senator has connected all the measures before Congress together, and he views them as parts of a whole. In the first place, here is the recommendation of the President; in the next place, here is the bill for the abolition of slavery in the District; and in the third place, here are the questions regarding the confiscation of property; and the honorable Senator thinks they are parts of a system.

Well, sir, I do not hesitate to say here that I dissent entirely from the conclusions of Senator Sumner, as stated in his resolution to make States territories. I do not look upon the States of this Union as gone and destroyed. The fundamental idea upon which we started in this contest was, that no State could take itself out of the Union; no State could destroy its existence as a State, or change its relations to the Union. We have not recognized State action. From the beginning we have considered all action as individual action, as having nothing whatever to do with the States as such.

Mr. Willey, of "Virginia:" If the honorable senator will allow me, he misstates my point: I say that in the excited state of the country these measures will be construed as parts of a system which, taken together, will destroy the Union sentiment by which it is hoped to reorganize the State governments.

Mr. Fessenden, of Maine: Let me say that that the Congress has no right to touch, by legislation, the institution of slavery in the States where it exists by law. But, sir, I say further that so far as the people have the power under the Constitution to weaken the institution of slavery, to deprive it of its force, to subject it to the laws of the land, to take away political influence, they have the right to do so.

Why, sir, do you suppose we came into power to sit still and be silent on this subject; that we came into power to do nothing; to think nothing; to say nothing lest by some possibility a portion of the people of the country might be offended? That was the argument of the honorable Senator from Indiana, Mr. Wright, this morning, as I understand it.

Sir, reflect: have we not duties to perform with our opinions? Can we defer the consideration of some of these subjects? Are they not before us everyday? Do they not meet us at every turn?

This question of the abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia, I have stated, has been always most nearest my heart. Gentlemen say it is a bad time to take it up. But, sir, whom do we injure? The slaves? The slave will bear the injury. The owner? What claim have the owners of slaves have upon us. They knew one day this day would come. We can say this thing should not exist where we have the power to abolish it.

Let me call attention to one fact. Virginia has as much territory as all New England. It is vastly superior to it in every particular. It has mines, it has water power unequaled, it has facilities for trade which are not surpassed in any quarter; it has all the elements of greatness, for manufacture, for commerce, and for agriculture. In the days of the Revolution it had more population than all New England; more commerce, more wealth. Compare the State of Virginia as it was when the rebellion broke out, with New England, and see the difference between the two. At that day you had less than a million of white population and we had three millions. In all the branches of life we were vastly your superiors. What is the reason for this? Can you give any for the difference except the fact that you had an institution which we had not What I say about Virginia is true of all the slave states. Slavery is a curse and a ruin that the nation can no longer afford.

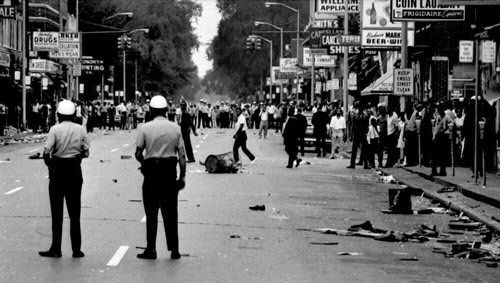

Note:" Slavery is a curse and a ruin that the nation can no longer afford:" this is the policy statement of the Republican Party. By 1860, the politicians in the Northern and Western States were keenly aware that the vast territory of the United States, west of the Mississippi, was ripe for development which meant millions of people were being drawn into it, and those millions—white people of European ancestry—were infected with an incurable antagonism toward Africans, whether free or not. At the same time, the politicians were seeing the number of free Africans immigrating into their States to be increasing, creating rumblings that were resulting in the passage of laws of exclusion. At the same time, also, they were seeing that the birth rate of the Africans was causing their total population to increase annually. Four million Africans were residing in the United States, in 1860, and it was clear to the Republican politicians that somehow a start had to be made in integrating them into society as free persons, if the country was to maximize its economic potential.

Mr.

Morrill, of Maine: There are objections to this bill which cannot

stand. An objection is brought that it does not provide for the care and

custody of infant children discharged from service, and we are told that this

bill turns the children out upon the world as free, without measures to support

them. In my investigation, one fact stands out: almost all infants have

mothers, though it is a little question about their fathers. If you

confer on the black population of the District the boon of freedom, they ask no

favors of you; they do not ask your charity; they do not ask you to assign

guardians; they do not ask you to find persons to take charge of them. Just

take your feet off these people, let them up, give them their rights, and my

word for it they will take care of themselves.

Mr.

Morrill, of Maine: There are objections to this bill which cannot

stand. An objection is brought that it does not provide for the care and

custody of infant children discharged from service, and we are told that this

bill turns the children out upon the world as free, without measures to support

them. In my investigation, one fact stands out: almost all infants have

mothers, though it is a little question about their fathers. If you

confer on the black population of the District the boon of freedom, they ask no

favors of you; they do not ask your charity; they do not ask you to assign

guardians; they do not ask you to find persons to take charge of them. Just

take your feet off these people, let them up, give them their rights, and my

word for it they will take care of themselves.

Now, in regard to the provision for old men. I admit the price of $150 is arbitrary, but I think all will agree with me that $150 is not too much to take care of persons sixty or seventy years of age. When these people have been used all their lives in the service of another, it seems to me at least to be enlightened charity to provide this much for their support when they are set free.

April 2, 1862

Mr. Sherman, of Ohio: It is proposed to emancipate the slaves of this District. I am informed that the number of slaves in the District is less than fifteen hundred. To add one thousand to the number of free negroes in this District, now about 11,000, is a matter of very small importance. It is the idea of emancipation which makes the issue such a big deal. It is this reason that has excited the hostility of Mr. Davis, of Kentucky, and Mr. Willey, of Virginia.

I would

abolish slavery simply for its affect on property. The abolition of

slavery in this District will bring here active, intelligent mechanics and

laboring men, who never will compete with the labor of slaves, and who,

finding none here but free men, will develop the great advantages of this city.

I would

abolish slavery simply for its affect on property. The abolition of

slavery in this District will bring here active, intelligent mechanics and

laboring men, who never will compete with the labor of slaves, and who,

finding none here but free men, will develop the great advantages of this city.

There is another reason. This is the best place to try the experiment of emancipation. We shall set the example which the slave states will surely one day follow.

There is another good reason to begin emancipation in this place. This is a very paradise for free negroes. Here they enjoy more social equality than they do anywhere else. In the State where I live, we do not like negroes. We do not disguise our dislike. As my friend from Indiana, Mr. Wright, said yesterday, the whole people of the northwestern States are opposed to having many negroes among them, and that principle of prejudice has been ingrafted in the legislation of nearly all the northwestern States. Here there is but little prejudice against them, and here they have the best chance of thriving. Here they are the laborers, the hackmen, the servants, and are of great service.

There is the objection raised by the Senator from Maine that the bill does not provide for colonization. If it is our duty to emancipate these slaves, it is equally our duty to give the negroes the right of choice whether they will live here in a land where they will always be held as a subordinate race, or try the experiment of freedom in another and more favorable clime. I think it a just idea that we, as a nation, owe these people the obligation to allow them to develop their freedom and their capacity to govern themselves in a country where they will not be met at every step with caste and prejudice, hate and contumely; where they can exercise no political rights; where they cannot vote; where they cannot serve as jurors; where they cannot exercise any of the rights of freemen. When you give negroes freedom in this country you give them freedom stripped of everything but the name. You make them freemen without the right to govern themselves.

Let me say another thing. We are the majority in this body. We are the majority in the other House. We have a Republican administration. If we do not show to the people of the United States that we have a definite policy, and have manhood to stand by it, we ought to be overthrown. We ought to adopt a policy and adhere to it. We ought now to abolish slavery in the District. We ought religiously to abstain from all interference with the domestic institution of slavery in the States. We ought to stand by the Constitution as it is, by the Union as it is. Whether rebels are in arms or not, our duty is to stand by our pledges, and I, for one, will do it.

Note: Here is the first whiff of the great danger to the liberties of the people that war brings. The experience of one hundred and fifty years of American history demonstrates that the paper limits imposed on Government by the Constitution are ignored by those, whoever they are, in control of the Government when war is instigated.

Mr. Davis, of Kentucky: Will the gentleman permit me a moment. Mr. President, the two gentlemen, Mr. Morrill and Mr. Collomer, when I occupied the floor on this subject a few days ago, propounded several questions to me. I now ask their courtesy to permit me to return the compliment.

Mr. Morrill: Whom does the Senator want to question?

Mr. Davis: Both of you.

Mr. Morrill: You may begin with me.

Mr. Davis: Tell me whether property in slaves can exist or not, whether those who are called the owners of slaves can have a property in them or not? Second whether Congress can take from the citizens of this District who own real estate, that real estate, or not, and if they answer the second question in the negative, to point to the clause in the Constitution that create a different title to slaves and real estate.

Mr. Morrill: If I understand the Senator he inquires of me whether I recognize the right of property in a slave?

Mr. Davis: That is the first question.

Mr. Morrill: Very well, sir; I will answer you in a trice. I do not hold in the common acceptation of the term that an owner has property in his slave. I do not hold that the owner of a slave owns his slave as he owns his horse. I hold that the sense of mankind does not regard property in a slave as in a horse or in lands. That is repugnant to the common sense of mankind throughout the civilized world; and in this instance I hold that the title or claim which the owner of a slave has to his slave in this District rests entirely upon an act of Congress, and that act does not establish the relation of owner and property but establishes the relation of master and slave. Repeal that law and slavery topples and falls instantly to the ground. Therefore, my answer is, that I do not recognize the right of property in slaves; but I do recognize, under the act of Congress of 1801, the relation of master and slave.

Mr. Davis: My friend's answer was not quite as broad as my question. It was not limited to slaves in this District, but it was a question of general application, whether the owners of slaves in the District or out of it have a property in slaves or not.

Mr. Morrill: The principles I have now laid down are applicable to any case in the States. I hold that there is no precise property in slaves, in the sense in which we have property in lands, or property in horses or other animals. It has a different origin; slavery is founded on force, originates in force, never is maintained anywhere except by a statute which is founded in force. Slavery is abhorrent to the common sense of mankind.

Mr. Davis: I laid down a few days ago this proposition—and I defy the Senator from Maine to refute it—that there is no positive written law which establishes property in a slave or in land or in a horse, that the law upon that subject arises, from the uniform custom and usage of the civilized world.

And I laid down this further proposition: that my legal right to my slave was precisely of the same nature and character with my legal right to my land; and that if I were a citizen of the District of Columbia Congress would have no more right to deprive me of the one subject of property than of the other.

The gentleman denies that property can exist in a human being. That is his broad proposition. Upon that point I am totally at issue with him, and I am sustained by the Constitution of the United States wherever the question has been mooted and decided. The Senator now concedes explicitly that Congress has no power to take from the people of this District their houses or their lands, or any property but their slaves, as I understand him. I ask the gentleman for the law or the provision of the Constitution which forms the interdict and he gives me the provision that no citizen's property shall be taken for public use except by due process of law and just compensation. I maintain that that prohibition on the power of Congress applies as legitimately and with as much truth and logic to slaves as it does to real estate.

My proposition a few days ago was that slavery was general and that the abolition of slavery was local; and that proposition I sustained by reading from the opinion of Chief Justice John Marshall in the Antelope case. Marshall decides the principle broadly, that slavery exists by public national law.

Mr. Morrill: I take issue with that point. Slavery is acknowledged by international law only in such nations as recognize it.

Mr. Davis: No, sir. Chief Justice Marshall decided that slavery and the slave trade existed by national law, and that this national law may be repealed locally by the proper legislation of every country upon the earth; and that this national law exists in every country save in those countries where, by positive enactment, it has been repealed.

I do not

deny that slavery is contrary to the law of nature, but I say that the law

created by the usages of mankind overrules the law of nature in relation to

this subject. What is the law of nature? When this traffic in slaves was

indulged in by the civilized world, and the States of Massachusetts and Rhode Island were inundating the colonies with slaves torn from Africa, and selling them

for a price, what was the law of nature then in Massachusetts that indulged

such a traffic; and what was the law of nature in the civilized world? What is

the law of nature now in Turkey and in China? What was the law of nature in Europe two centuries ago? What is the law of nature in Utah?

I do not

deny that slavery is contrary to the law of nature, but I say that the law

created by the usages of mankind overrules the law of nature in relation to

this subject. What is the law of nature? When this traffic in slaves was

indulged in by the civilized world, and the States of Massachusetts and Rhode Island were inundating the colonies with slaves torn from Africa, and selling them

for a price, what was the law of nature then in Massachusetts that indulged

such a traffic; and what was the law of nature in the civilized world? What is

the law of nature now in Turkey and in China? What was the law of nature in Europe two centuries ago? What is the law of nature in Utah?

The law of nature varies with the altered condition of civilization and the condition of the world; and what is the law of nature in one age and in one country and in one generation, is not the law of nature universally.

It is because of this want of uniformity in the law of nature, and because there is no common tribunal to define and establish what the law of nature is, that it has been uniformly decreed to be subservient to the positive laws of any country, and to the laws of nations, as established upon the usages of the civilized world.

Let me read from Chief Justice Marshall's opinion:

"That slavery is contrary to the law of nature will scarcely be denied. That every man has the natural right to the fruits of his own labor is generally admitted; and that no other person can rightfully deprive him of those fruits, and appropriate them against his will, seems to be the necessary result of this admission. But from the earliest times war has existed, and war confers rights in which all have acquiesced. Among the most enlightened nations of antiquity, one of those was, that the victor might enslave the vanquished."

That was once a principle of the law of nations as recognized by the whole world. I admit that the principle has been exploded by the Christian civilization of this age. Let me read again from Marshall's opinion.

"Slavery, then, has its origin in force; but as the world has agreed that it is a legitimate result of force, the state of things which is thus produced by general consent, cannot be pronounced unlawful."

What does Chief Justice Marshall here decide? That although slavery has its origin in force and is against the law of nature, yet as it has been universally recognized by the civilized world, it exists and is acknowledged by the law of nations.

As Marshall says:

"Throughout Christendom this harsh rule has been exploded, and war is no longer considered as giving a right to enslave captives. But this triumph of humanity has not been universal. The parties to the modern law of nations do not propagate their principles by force; and Africa has not yet adopted them. Through the whole extent of this immense continent, so far as we know of its history, it is still the law of nations that prisoners are slaves. Can those who have themselves renounced this law, be permitted to participate in its effects by purchasing the beings who are its victims?"

Here is the principle to which the honorable Senator from Maine referred:

"Whatever might be the answer of a moralist to this question, a jurist must search for its legal solution in those principles of action which are sanctioned by the usages, the national acts, and the general assent of that portion of the world of which he considers himself as a part, and to whose law the appeal is made.

If we resort to this standard as the test of international law, the question is decided in favor of the legality of slavery and the slave trade. Both Europe and America embarked in it; and for nearly two centuries it was carried on without opposition and without censure. A jurist cannot say that a practice thus supported was illegal, and that those engaged in it might be punished either personally, or by deprivation of property."

In this commerce, thus sanctioned by universal assent, every nation had an equal right to engage. How is this right lost? Each may renounce it for its own people; but can this renunciation affect others? No principle of general law is more universally acknowledged than the perfect equality of nations. It results from this equality that no one can rightfully impose a rule on another. A right, then, which is vested in all by the consent of all, can be divested only by consent; and this trade, in which all have participated, must remain lawful to those who cannot be induced to relinquish it."

Note: Of course, we know that, since World War II, this rule of international law, with the appearance of the United Nations, is in decline. At least the United States Government considers it so. We insist on meddling in the domestic policies of independent nations: North Korea, Iran, Russia, Cuba, and Iraq, to name a few.

Mr. Morrill: Will the gentleman permit me. Slavery was universal because it was made so by the acts of the several nations themselves. It was not a law of nations; it was the law of each nation, and therefore of all; that a nation might repeal it while another does not, shows it is not a law of nations. Another thing, it was never a law of nature. The laws of nature can never change, until nature changes.

Mr. Davis: The gentleman is still mistaken. I admit that the law of nations was made by the practice of nations, and that is what Marshall says. No Senator here can find any positive written law of any nation upon the earth sanctioning the slave trade, except the Constitution of the United States, which continued the traffic until 1808.

I will try another authority; it is Justice McLean, who the Senator from Massachusetts the other day praised so. It was a case of this character. A slave had eloped from Kentucky into Ohio where a certain citizen gave him aid in making his escape to Canada. The owner of the slave sued this citizen for damages for having aided the slave in his escape. Defense counsel argued that there was no positive law, no statute enacted in Kentucky which established slavery. Judge McLean concede that to be the fact; but instead of that being a denial that the right of property existed in the plaintiff, he expressly stated in words that it was no defense at all, pointing out that in our colonial governments no general provision existed for the surrender of slaves. From our earliest history, he said, slavery existed in all the colonies.

How did it exist in the colonies? Not by positive enactment, not by any positive law; it existed only by public, national law, based upon the usage of the civilized world. That is the origin and foundation of the property of the owner of a slave to that slave.

Judge McLean put the principle this way:

"Property takes its designation from the laws of the States. It was not the object of the Federal Government to regulate property. A Federal Government was organized by conferring on it certain delegated powers, and by imposing certain restrictions on the States. Among those restrictions it is provided that no State shall impair the obligation of contract, nor liberate a person who is held to labor in another State from which he escaped. In this form the Constitution protects contracts and the right of the master, but it originates neither."

There is a decision in which the right of the master to his slave is expressly recognized, and yet the honorable Senator from Maine assumes that there can be no property in slaves.

Now, Mr. President, we are entering a new epoch. We have some great heresies attempted to be put into practice in the southern States and they all have their origin in Massachusetts. The State of Massachusetts entered early and largely, and with great profit, into the slave trade; they brought the mass of the slaves that were imported from Africa into the colonies and into the States up to 1808. After having themselves planted this obnoxious weed in society, as soon as the Constitution prohibits them from continuing this lucrative traffic they turn around and want to emancipate the slaves they had before sold to innocent parties!

The honorable Senator from Massachusetts, Mr. Sumner, in his splendid oration upon the subject of slavery the other day, said that slavery was not destroyed by local legislation in the British West Indies but by the national government. That is true. If the people of England had had the same financial interest in slaves as did the West Indies planters, they would have sung a different tune. Suppose the honorable Senator now and every one of us owned two thousand acres of cotton land, and had upon it a hundred slaves, and the annual produce of this estate of land and labor was one thousand bales of cotton, yielding an income of $50,000. Suppose every Senator was thus possessed of this property, I ask how many of these Senators, without regard to their locality or their present opinions, would be willing to give up such an estate for nothing? The man is green indeed who believes that one of them would. (Laughter).

We are the creatures of the circumstances that surround us, and of education. If you and I had been born and reared in Constantinople, we should have been Mussulmans. If we had been brought up in desolate Utah, the honorable Senator from Massachusetts might have been a polygamist. (Laughter)

Now, Mr. President, we have a party in this country called Abolitionists. There is a party in this country who believe that their mission is to overthrow slavery, and they are marching to this work regardless of the Constitution of the United States, of all its compromises, and of all the rights which it secures to the States and to the citizens. Sir, it is in defense of the Constitution, with all its limitations of power, with all the rights that it secures to the States and to the people, with all its restrictions on the Congress, that the great Union party to which I belong has drawn the sword. Mr. President, we stand upon the Constitution as Washington and his associates made it, as it has been expounded by the Supreme Court, and we are fighting this war for those immortal principles of liberty and of security to the rights of property, without which that sacred instrument could never have been formed and agreed to by the States. The Constitution is the ark of our liberty; it is the bond of our Union. When that bond is broken the Union is gone forever. I say to you Abolitionists that you are worse enemies of the Union than Jeff Davis and his hosts in battle.

Note: Here, of course, we see the reason "States Rights" has a bad odor. What we must not ignore, however, is that the fault, if it was a fault in 1787, lies with the framers who inserted the principle into the plain meaning of the Constitution. The Constitution was Mr. Davis's ark of liberty, to the Africans, though, residing in the United States, in 1862, it was the iron hammer that welded their chains.

Mr. President, it has been frequently inquired what brought about this war. I will tell you what I religiously believe, that the States of Massachusetts and South Carolina and their mischievous isms have done more to bring about our present troubles than all other causes. I believe that if it had been possible to unmoor those two States and drift them away into the ocean together, and let them fight out their antagonism side by side in some distant sea, the rest of the States would have got along most harmoniously. I religiously believe that those two States have been the hotbed of ambition, of religious, social, and political heresies and isms, and they have been pressed upon the rest of us with an energy that has brought us to our present great difficulty. If there is any people that ought to be held to special account for the present condition of the country, it is the people of Massachusetts and South Carolina.

Mr. Morrill: I understand the proposition of the honorable Senator from Kentucky to be this: that he has precisely the same right to his slave that he has to his horse or his lands, and that the origin of the right of property in slaves and the origin of the right of property in lands is one and the same.

This is not the notion common to American jurisprudence; nor is it a notion that is common to the country from which we originate. Instead of a man's having the same claim, the same sanction, and the same right to a slave that he has to his property, the law of England, the law of the mother country, has always held that the right to slaves, that property which was claimed in slaves, was in violation of natural right, and was in violation of natural law. Why, sir, the great commentator on English law lays down this proposition—that the origin of the right of property springs from the Deity. That is his distinction. The origin of the right of property springs from the Almighty, maker of heaven and earth; and there is no origin outside of it.

Note: So it's "God's" fault.

The honorable Senator says, `show me a statute on this subject, giving me a right to my horse, which does not give me the same right to my slave.' Well, I will refer him to a positive statute on this subject,

"And God blessed them"—

Mr. Davis: Will the honorable Senator permit me to ask him a question?

Mr. Morrill: When I have read my authority I will.

"And God blessed them, and God said unto them, be fruitful and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it; and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth."

The commentary of the great English commentator runs back to that as the origin of the right of property; and here is the obvious distinction between the right of persons and the right of things. Man has dominion over things; he has no dominion over persons—

Mr. Davis: I will ask the honorable gentleman from Maine if he ever knew any property to be recovered in a court of justice upon that law, or ever knew a claim to property to depend on the law which he has just read, in a court of law?

Mr. Morrill: We never had any occasion to plead that statute in my part of the country, yet it is always recognized. (Laughter) I only state in opposition to the notions of the Senator what every lawyer knows to be the common learning of the law, and that is the distinction between persons and things. Things are subjected to the dominion of man; persons never, never! And let me say that the law of nature never changes. Men may disregard it, communities may disregard it, but the law stands.

Mr. Wilmot: Why does not the gentlemen propose compulsory emigration or colonization? If the races cannot live together, then surely we should adopt compulsory emigration.

Mr. Browning: We are acting upon too small a scale to justify us in broaching so momentous a question as that is at this time. The time may come when compulsory colonization may be found necessary for the good of both races. If we were in a condition to remove the colored race from our midst, and place them elsewhere, where they would be better provided for, where they would be given the full stature of freemen—they never can attain to the full stature of freemen in our midst—if we are prepared to remove them, give them pecuniary aid, settle them, for a time to protect them and school them until they can take care of themselves, I would have no scruple about making it compulsory emigration or colonization. But, sir, the subject now before us is so small a matter, scarcely a drop in the bucket; you may strike off the bonds of every slave in the District today and there is not a slave State in the Union that will feel the effect of it one atom. (nor a free State.)

I further assert what we have often said, that freeing slaves in the District does not justify the charge of any intention of interfering with the institution of slavery in the States. We disclaim the power to do so, we disclaim the right to do so, and we disclaim the intention to do so. With slavery in the States we have nothing on earth to do. It is a thing of local law.

But here in the District we have the right to deal with it. Just as long as they remain among us they are free negroes; they are nothing else; they are a poor, degraded caste, and I am afraid always will be. When you come to propose the admission of the negro to social equality and to family alliance, it is a test that reduces all our sympathies to dross and ashes. It is a test that none of us can bring ourselves up to.

Mr. Bayard: Mr. President, let us look to the Fifth Amendment, that no man shall be deprived of property without due process of law and just compensation. Well, sir, what is the effect of this bill? Gentlemen, when they are abolishing slavery in the District tend to mix up with it their ideas of confiscation. On what principle is it, sir, that you can require of any man if you take his property, a condition that he prove himself loyal to your Government? A man may be guilty of murder; but until his conviction you have no right to confiscate his property. You admit the necessity of compensation but you would have a board of commissioners determine on the question of loyalty and withhold payment if the finding is disloyalty. What is that but punishment, without trial, without offense known to the laws?

Sir,

I know that personal liberty is dead in the United States under the stale plea

of State necessity, but I am not aware that the Government, in any

State in which the courts are open, has undertaken to confiscate the property

of a citizen without trial. It is an onward step. It is a further step in the

destruction of free government and the establishment of a government of will in

this country, depending upon the will of the present administration.

No general rule or principle, no written constitution, meant, as it is, to

guard against the violation of private rights, seems to have the slightest

control over the actions either of the Executive or of Congress.

Sir,

I know that personal liberty is dead in the United States under the stale plea

of State necessity, but I am not aware that the Government, in any

State in which the courts are open, has undertaken to confiscate the property

of a citizen without trial. It is an onward step. It is a further step in the

destruction of free government and the establishment of a government of will in

this country, depending upon the will of the present administration.

No general rule or principle, no written constitution, meant, as it is, to

guard against the violation of private rights, seems to have the slightest

control over the actions either of the Executive or of Congress.

Mr. President, I am aware that there is a kind of answer given by certain members of this body that slaves are not property. Well, sir, it is not worth an argument. The foundations of property do not rest in the law of nature; they rest on the complex relations of civilized society.

Sir, if this war is to be prosecuted for the preservation of the Constitution, its principles must be adhered to during the prosecution of the war. We are not wantonly to violate it because gentlemen have a theory it will be a benefit to the District to set slaves free here. Honorable Senators may think that adherence to the provisions of the Constitution is of little moment now when they are in power; but I tell them that they will find hereafter that there is a Nemesis in all human affairs, and that it is far easier to throw away the precious jewel of civil liberty than to recover it when it is lost.

I pass now, for a moment, to the issue of the relation of the races. Mr. Sherman expects that the passage of this bill will produce a paradise in the District, but I tell him it will not be so in a few years or so, to the white men. The question of the relation of the races depends upon relative numbers. The honorable Senator from Ohio, with thirty-six thousand negroes in his State out of two millions three hundred and fifty thousand population, can form no opinion as to what would be the effect of emancipation in the State of Maryland with one fourth of the population negroes.

Sir, I tell him that the skilled labor will not come where the black race exists as freemen half as soon as where they exist as slaves. It is the principle of equality which the white man rejects where the negro exists in large numbers. It is that which creates the antagonism of race. The people of Indiana restricted the immigration of the inferior race into their State years ago by constitutional provision. The people of Illinois have done so recently. The people of Ohio will do it yet; the people of New Jersey will do it yet; the people of Pennsylvania will do it yet; and this bill and similar bills will force it on them. You cannot overcome the law of nature; I speak of the primary law of nature, the instinct of race. The white man will not consent in this country, that the mass of the white people shall amalgamate with the blacks, and be reduced to a level with the Mexicans.

Gentlemen may war, if they please, against the law of nature and the characteristics of the race; but though they may have the power today to enforce by legislation doctrines and measures which will be injurious to the country, rely upon it its reacting sense will teach them that their doctrines and their theory are a fallacy.

The Presiding Officer: The question is on the passage of the bill manumitting the slaves in the District of Columbia, upon which the yeas and nays have been ordered.

The Secretary proceeded to call the roll. The result was announced—yeas 29; nays 14. So the bill was passed. (By almost a two to one margin.)

In The House of Representatives Of The United States:

April 10, 1862

Freedom for the Slaves in the District

The CHAIRMAN. The Chair decides that the bill can be laid aside.

The motion was agreed to.

Senate Bill No. 108, being an act for the release of certain persons held to service or labor in the District of Columbia, was next reached on the Calendar.

Mr. Webster: I move that that bill be laid aside. (Laughter)

The motion was not agreed to; and the bill was before the committee for consideration.

Mr. Thomas, of Massachusetts: Mr. Chairman, I avail myself of the indulgence of the committee to say something upon the relation of the `seceded states' to the Union, the confiscation of property, and the emancipation of slaves in such States.

The peculiar feature of our civil policy is, that we live under written constitutions, defining and limiting the powers of Government and securing the rights of the individual subject. Our political theory is, that the people retain the sovereignty and that the Government has such powers only as the people, by the organic law, have conferred upon it. Doubtless these inflexible rules sometimes operate as a restraint upon measures which for the time being seem to be desirable. The compensation is that many times our experience has shown that in the long run the restraint is necessary and wholesome.

Designed as the bond of perpetual union, and as the framework of permanent Government, we should be very slow to conclude that the Constitution lacks any of the necessary powers of self-defense and self-preservation. (Quite a different thing.)

But when a measure is in apparent conflict with the Constitution, we may well pause to consider whether after all the measure is necessary, and whether we may not bend to the Constitution rather than that the Constitution should give way to us. When we make necessity our law-giver, we are very ready to believe necessity exists.

Nor are we to forget that the Constitution is a bill of rights as well as a frame of government; that among the most precious portions of the instrument are the first ten amendments; that it is doubtful whether the people of the United States could have been induced to adopt the Constitution except upon the assurance of the adoption of these amendments; which are our Magna Carta, embodying the securities of life, liberty, and property.

Mr. Chairman, there is but one issue before the country, and that is whether the Constitution shall be the supreme law of the land. The Constitution was formed by the people of the United States. It acts not upon the States, nor through the States upon us as citizens of the several States, but upon us as citizens of the United States, claiming on the one hand our allegiance and giving to us on the other its protection. It is not a compact between the States or the people of the several States. It is itself a frame of Government ordained and established by the people of the United States.

Note: Let's look close at this: How was the Constitution "formed by the people of the United States?" According to the preamble, "We the People of the United States [ordained] and establish[ed] this Constitution of the United States of America." Restating this, does not answer the question, how? The people did not come together in a national convention and ratify it, they came together in their native States, in convention assembled, and each convention, on behalf of the people of their State, assented to join the Union which became known among the nations of the world as the "United States of America."

Mr. Thomas is also plainly wrong in his statement that the Constitution "is not a compact between the States." The instrument, itself, defines expressly the mode in which the framework—the Constitution—was "formed." Article VII reads: "The Ratification of the Conventions of nine States, shall be sufficient for the Establishment of this Constitution between the States so Ratifying the Same."

Thus, the Constitution became operative upon the consent of less than the whole people residing in North America, in 1789; the "whole" people of the United States at the time the Constitution sprang into operation was the people of the nine states that first ratified it, and these people did so in their sovereign capacity as citizens of their native States. And, in ratifying the instrument, no one can reasonably dispute the plain fact that their States retained sovereignty (and, thus, full control) over their domestic policies.

The very essence of a Nation is found in the fact that it, and only it, controls its domestic policy. Iran is a Nation if but only if it is solely in control of its domestic policy—Let's obtain nuclear power for our people. Other nations may quite legitimately refuse to engage in economic relations with Iran, as a result; but they cannot claim, by the law of nations, the right to wage war against Iran to prevent its domestic policy from gaining the result sought.

What seems to be happening, in terms of the law of nations, is that nations which adopt certain domestic policies are deemed to lose the right to be let alone. When Germany adopted the domestic policy of exterminating Jews, it lost the right to be let alone; and even if it had not invaded France, igniting World War II, the United Nations, in terms of evolving international law, had the right to invade its territory and topple its government and install a substitute in its place. There is nothing in this emerging principle that justifies the United States' invasion of Iraq, or its threats to attack Iran.

Such being the relation of the Government of the United States to its citizens and to the States, the first question that arises is, how far this relation is affected by the fact that several of the States have assumed, by ordinances of secession, to separate themselves from the Union. An ordinance of secession has no legal meaning or force, it is wholly inoperative and void.

Note: Mr. Thomas, in the real world, could hardly be more wrong. Whether lawyers may argue over the nice question of the "legality" of Virginia's ordinance of secession, it clearly had, in fact, force; and it was hardly "inoperative and void." On the basis of it Virginia was at war with the rump of the United States.

The act of secession, therefore, cannot change in the least degree the legal relation of the State to the Union.

Note: As of April 10, 1862, under the law of nations, the "legal relation" of Virginia to the Union was that of a public enemy, a belligerent, entitled to exercise all the rights recognized by the law of war. Whether it might gain the status of a "nation," recognized as such by the law of nations, depended strictly upon its military success in the field. But that is the test all nations must face when their independence is challenged by an aggressor's force of arms.

It is the necessary result of these principles that no State can abdicate or forfeit the rights of its citizens to the protection of the Constitution. The primary, paramount allegiance of every citizen of the United States is to the nation, and the State authorities can no more impair that allegiance than a country court or a village constable.

Note: Again, Mr. Thomas is wrong: allegiance, as the framers understood it, was primarily owed to the State of which a person was a citizen. It was the fact that the person was a citizen of the State that made the person a "citizen of the United States." Mere habitation within a State did not, in 1789, make one a citizen of that State. (The Nature of American Citizenship)

Of course, the people of a State can abdicate or forfeit their rights as citizens of the United States, by meeting in convention assembled and by a majority of votes agree to the secession of their State from the Union. That is how the framers designed the system of national government, in the abstract. In the real world, though, they knew the seceding States would have to defend themselves against the natural threat of conquest the act of secession would create. It seems hardly imaginable, doesn't it, that, had the framers been asked whether they intended the Federal Government to have the power to use force of arms to coerce the people of Virginia to remain subject to its jurisdiction, they would have nodded their assent?

Now, in case of conquest, even though the people of the conquered territory change their allegiance, their rights of property remain undisturbed. The modern usage of nations would be violated if private property should be generally confiscated and private rights annulled. When, therefore, States are reduced to territories, the national Government could not abolish slavery therein, except under the power of eminent domain, and by giving just compensation.

Note: Again, Mr. Thomas is wrong, but he is striving to reach a goal, refuting, with abstract argument, the right of the Congress to free the slaves. The right of property in men (i.e., the right to claim the service or labor of a person) can only be recognized by the domestic policy of the State. If the State is now a mere territory of the United States, it is for the Federal Government to decide its domestic policy.

What, then, it may be asked, is the legal character of this great insurrection? The answer is, it is a rebellion of citizens of the United States against the Government of the United States. Nothing the President said can be more explicit: `I, Abraham Lincoln, in virtue of the power vested in me as President, have thought fit to call forth the militia to suppress [rebellion] and enforce the laws.' Thus, then, this is not a conflict of States, nor is it a war of countries. It is a conflict between Government and its disobedient subjects. (How the framers must turn groaning in their graves: their sons, it turns out, are "subjects" of the "Government" controlled by Republicans.)

The difference between a war and a rebellion is clear and vital. War is the hostile relation of one nation to another, involving all the subjects of both. Rebellion is the relation which disloyal subjects hold to the nation. The legal relation between them is not that of war, though the rebellion has assumed gigantic proportion; the array of numbers does not change the essential legal character. It is still treason—the levying of war against the United States by those who owe it allegiance.

Note: Mr. Thomas needs to read the Constitution more carefully. The definition of "treason" is found in Article III which deals solely with the Judicial Power of the United States. Its provisions inform the Judicial Branch what is and is not "treason." Section 3 reads: "Treason against the United States shall consist only in levying war against them, or in adhering to their enemies." The problem of logic for Mr. Thomas lies in the framers' use of the plural pronouns, "them" and "their." The Constitution, as the framers wrote it, did not recognize the entity labeled "The United States" to be an "it."

For example, as long as General Lee was a citizen of Virginia and Virginia was a member of the Union, his allegiance to Virginia required him to avoid "levying war" against the Union of which his native state was a part. Once, Virginia seceded, however, and found herself being invaded by armies of the United States, under the control of the Republican party, General Lee's duty, if he wished to remain a legitimate citizen of Virginia, was to defend her borders against the United States. (Did General Lee commit Treason?)

While using the powers and appliances of war for the purpose of subduing rebellion, we are by no means acting outside the scope of the Constitution. We are using precisely the powers with which the Constitution has clothed us for this end. We are seeking domestic tranquility by the sword the Constitution has placed in our hands.

Note: "We are seeking domestic tranquility by the sword."They, in control of the Federal Government, were using it to conquer the Confederate States of America, reduce them to the status of territories, and thereby take control of their domestic policies.

It is a plain proposition, that in seeking to enforce the law we are, as far as possible, to obey the law. We are not to destroy in seeking to preserve. The people do not desire a bitter and remorseless struggle over the dead body of the Constitution. We may raise armies and pour out treasure and life blood of the people, but we cannot die well for the Republic, unless we keep clearly in view the end of all our labors, the Union of our fathers and the Constitution which is its only bond.

The bills and joint resolutions before the House propose, with some differences of policy and method, two measures: the confiscation of the property of rebels and the emancipation of their slaves. The acts of confiscation proposed would defeat the great end the Government has in view: the restoration of order, union, and obedience to law. They would take from the rebels every motive for submission; they would create the strongest motive for resistance. In the maintenance of the Confederate Government they might find protection, in the restoration of ours, spoliation. You leave them with the great weapon of despair.

Note: At this time, with the Union sweep of Missouri, Arkansas, Kentucky, and western Tennessee, and with McClellan moving toward Richmond on the Yorktown Peninsula, there was a feeling in the Congress that the war might come to a quick end; just a few more months, the conservative men were thinking, and it would be over and things going back to normal.

Apart from the injustice of these acts of sweeping confiscation, I have not been able to find in the Constitution the requisite authority to pass them. The acts are defended on the grounds that they constitute punishment for crime and that they are justified by the war power of the Government. But, as to the concept of "crime," the Constitution expressly denies Congress the power to impose ex post facto laws, and it commands that no person can be deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law. To do so, the Government must indict him, and try the issue of his guilt by trial of his peers. As to basing confiscation on the war power, such power is limited by the law of war which does not recognize the right of the Government to seize private property, except in precise circumstances, none of which are applicable here. By the modern usages of nations private property on the land is generally exempt from confiscation.

Note: Mr. Thomas's argument of abstractions was intended to lead the audience to the conclusion that, since the rebels are still citizens of the United States, they are entitled to the rights defined in the Bill of Rights, and thus their private property cannot be taken unless those rights are respected. But, of course, in the real world, it is plain that General Lee and his fellow Virginia citizens are in fact public enemies of the Union which the Republican party through its control of the Union Government means to conquer or destroy. And, yet though they are outside the pale of the Constitution, they are still entitled to the protection afforded them by the usages of nations, the law of war.

To avoid misconstruction, I desire to say that the power of Congress over slavery in the District is absolute; that no limitation exists in the letter or spirit of the Constitution. All that is required for abolishing slavery here is just compensation to the master. Desiring the extinction of slavery with my whole mind and heart, I watch the workings of events with patience. If in pursuit of objects however humane, if impelled by hatred and a desire for vengeance or retribution, we yield to such unconstitutional change, we shall destroy the best hope of freemen and slave, and the best hope of humanity this side the grave.

April 11, 1862

Mr. Nixon, of New Jersey: Mr. Chairman, I am in favor of the general principles of the bill. The gradual emancipation of the slave would have been more in harmony, would be more in accordance with my view of public policy, but if immediate emancipation, with just compensation, be the sentiment of the House, I am prepared to vote to remove the blot of slavery from the Capitol.

I have

not risen to comment on the details of the bill, but to throw some light on the

maladies afflicting the nation's life. The origin of our national troubles has

been traced to various sources. Philosophical gentlemen will tell you that this

is a contest between two forms of civilization; in irrepressible conflict

between antagonistic ideas of the objects and ends of Government; the one side

agreeing to the unity of the race and struggling for its emancipation and

political equality, the other side denying its unity, and trying to perpetuate

the distinctions of caste. The deduction from this view is that the war must go

on until one side annihilates the other. If this be true, if the mere existence

of slavery were sufficient to produce rebellion, then the Constitution is a

failure; the wisdom of the fathers who framed it, was folly; and the sooner we

strike hands with the southern traitors the better for us, and for mankind.

I have

not risen to comment on the details of the bill, but to throw some light on the

maladies afflicting the nation's life. The origin of our national troubles has

been traced to various sources. Philosophical gentlemen will tell you that this

is a contest between two forms of civilization; in irrepressible conflict

between antagonistic ideas of the objects and ends of Government; the one side

agreeing to the unity of the race and struggling for its emancipation and

political equality, the other side denying its unity, and trying to perpetuate

the distinctions of caste. The deduction from this view is that the war must go

on until one side annihilates the other. If this be true, if the mere existence

of slavery were sufficient to produce rebellion, then the Constitution is a

failure; the wisdom of the fathers who framed it, was folly; and the sooner we

strike hands with the southern traitors the better for us, and for mankind.

But it is not true. There was no need of such a contest. The history of the world, of our own country, prove that no such necessity existed. It was not the institution of slavery, but the ambition of southern men, that made slavery aggressive. It was not the desire for the emancipation of the slave, but the ambition of northern leaders, struggling to get into power, that made abolition aggressive.

Other differences arise from the confusion of ideas as to the relations of the States to each other and to the Federal Government, and the powers vested in the Government by the Constitution. A large class of southern politicians have long held that the Constitution does not establish a government acting directly on individuals, but that it is a mere compact to which the States are parties, and which may be dissolved at the will of either party.

Note: Of course, considering the issue in an objective light, using cold reason as the guide, it is clear from the undisputed historical evidence that, indeed, the Constitution did not "establish a government acting directly on individuals." Such a fact can only be true, in the application of cold logic and reason, if the Constitution was intended by its framers to control the domestic policy of the State, and not leave control in the hands of the people of the several States; to operate upon individuals, it is hardly likely the framers would have used language that specifies its ratification shall be through "the Conventions of nine States" and that the "Establishment of the Constitution" shall be "between the States ratifying the same." Instead, the framers would have logically specified that the "Establishment of the Constitution shall be between the peoples of the nine States ratifying the same."

The pestilent heresy of secession, with its brood of evils, is the offshoot of this false assumption. Hence, these men regard an ordinance of secession to be valid, absolving them of all allegiance to the Federal Government; and they call this war "coercion of sovereign States." It was just here that the late President (Buchanan, now dead) gave so much aid and comfort to the conspirators.

Note: The objective facts of history show conclusively that the political party in control of the Federal Government until November 1861 (the Democrats) followed reasonably closely the theory of the Union as the framers designed it; that is, "theory" applied in the abstract.

In his message to Congress (in December 1860) President Buchanan said that if a State seceded there was no remedy, because there was no power in the Constitution to coerce a State.

Note: Here, of course, President Buchanan was wrong. The Constitution gives the Federal Government the war power, the power to make war aggressively against any political entity that, in its self-interest, it considers necessary to conquer or destroy. That is the fundamental law of war, and it is that law that justifies, if at all, the Federal Government using the armed forces of the United States to attack independent nations, whether the nation attacked is Germany, Japan, Iraq, Iran, North Korea, or the Confederate States of America.

But it is not the State that is in rebellion and deserving punishment, but individuals who, acted upon by the laws of the United States, forcibly resisted their execution, and owing fealty to the Government, raised their hands for its overthrow. (As it affected them.)

The propositions now pending in this House and the Senate for the organization of territorial governments over the seceded States contain the germ of this fallacious reasoning. It was not so intended by the movers, but these propositions when carried to their logical conclusion, recognize the right in a State to secede. They assume that South Carolina, for instance, is out of the Union, and as she was not able to carry her territory with her, Congress should organize a territorial government over it. But how did South Carolina get out of the Union? Not by an ordinance of secession, because we (Republicans) all agree that these ordinances are void. Nor did she get out by the dissolution of a compact, because the ties that bind cannot be broken unless everyone unanimously agrees.

Note: This is silly. If you repudiate the crucial terms of the agreement—the terms that induced me to agree—your breach excuses me, it gives me just cause to assert the agreement is at an end.

Other propositions look to acts of emancipation of the slaves, not only as one of the objects of the war but also as an efficient means of carrying the war to a successful conclusion. The authority to do this is found by some in the false theory that States lose their right to hold men to service, through their domestic laws, in consequence of their pretended secession; and by others in some vague notion that the right exists as incident to the war power, as if the powers conferred upon Congress were intended by the framers to be elastic, expanding and contracting as the exigencies seem to demand. I do not say that the right of emancipation does not exist. I say it does exist by virtue of the President's war powers.

Note: This view has carried forward to the present day and it has led us to the Congress's present imposition of martial law upon the country; this is manifest in its suspension of the writ of Habeas Corpus, denying American citizens the right to be indicted, the right to communicate confidentially with an attorney, the right to trial by a jury of your peers.

I do not say that because the power is not expressly prohibited, it may be exercised; for every intelligent man will see at once to what consequences such a rule of interpretation would lead us. We do not look to see if the power is granted. We do not say that the power is not denied, and therefore exists. We say that it is not granted, and therefore does not exist.

Note: Mr. Nixon is twisting himself into knots here. Since the Constitution did not expressly prohibit the Federal Government from passing laws emancipating slaves, it necessarily follows, some would argue, that if the result wished for—in this case, emancipation—flows from the exercise of a power that is granted, such as the power to take care that the general welfare of the Union is furthered, then the Congress has the power to achieve the result. But the Constitution, in the Bill of Rights attached to it at the time it was ratified, expressly states that no person's property can be taken by Government without due process of law and without just compensation made. At no time did the Congress pass a law, to abolish slavery anywhere, which carried with it a provision to provide "just (market value) compensation."

This contest was not begun by us, it was forced upon us. As if to fill to the brim the cup of their wickedness, a peaceful vessel (the Star of the West), freighted with provisions for a starving garrison (accompanied by nine U.S. Navy warships and U.S. Army infantry aboard transports) was diverted from her errand of mercy (resupply a U.S. fort positioned inside a South Carolina harbor) by the cannon of the insurgents, and as if to make the cup overflow the fort at Charleston was invested by an army and the flag of the nation insulted and dishonored.

Then, thank God, the reaction came (as Lincoln instigated). The Government and the people woke from their strange apathy. The blood kindled in patriotic veins. The President's proclamation was issued and found a quick response. The President asked for 75,000 volunteers. What for? Not to coerce States, but to put "down combinations too powerful to suppress with the ordinary course of judicial proceedings." Not to emancipate slaves but to repossess the government. Not to execute new arbitrary laws, but to enforce the old laws.

I stand today with the Administration to secure the objects set forth by the President in his proclamation. There is the limit. This war is only justifiable because we intend to live by the Constitution. If we go beyond this limit we are guilty of the very transgressions of which we complain in them, and are making ourselves justly obnoxious to the charge of waging a war outside the Constitution to reduce the South to the will of the majority. It is always easy, in the whirl of fierce excitement, for men and nations to find pretexts to transcend the powers of the fundamental law.

The Constitution, it is alleged, was made for periods of peace. Its framers could not anticipate such a gigantic conspiracy against the national life, and therefore made no provision for it. Besides, the laws are always silent in the midst of arms. Necessity, everybody knows, is above the law.

Note: And here we find ourselves, today, reliving Mr. Nixon's experience. What possible "necessity" justifies the Congress suspending the writ of habeas Corpus, denying an American citizen the protection of the Bill of Right, in our day and age? What makes a cell in Cuba necessary for the incarceration of American citizens, that a cell in Illinois cannot provide? We are allowing the Congress, today, to confound the police power with the war power.

Is the Constitution silent? Did its authors, in their zeal to guard against the encroachments of the Federal Government, overlook the dangers to be apprehended by the encroachments of the people? The Constitution states it is the supreme law. It is the duty of the President to take care that law be executed. Congress has the power of war. It is only the amplification of the marshall's power to enforce the laws.

Mr. Blair, of Missouri: The charge has frequently been made that the President is without a policy. This is false. There can be no dispute as to the object of the war as far as he is concerned. He says in his annual message that he has been anxious that it "shall not degenerate into a violent and remorseless revolutionary struggle." (What else did he think it would be, when he started it?) "I have therefore," he says, "in every case thought it proper to keep the integrity of the Union prominent as the primary object of the contest." But it is objected to by some of those who aided in his election that he has not in aid of this object made the war upon the cause of the war, and decreed emancipation by an order as Commander-in-Chief as an effective agency in suppressing the rebellion.

Note: In April 1862, with huge military success in the field, many in Congress, aside from the radicals, think the war will be ended by June, and so the radicals, although pushing their agenda, are sitting back and waiting for the war to devolve into a remorseless struggle, at which point they will press Lincoln hard to issue a "proclamation" of emancipation for the slaves. Lincoln will do it, only when the pressures of the war make him frightened that Kentucky is about to go over to the Confederacy.